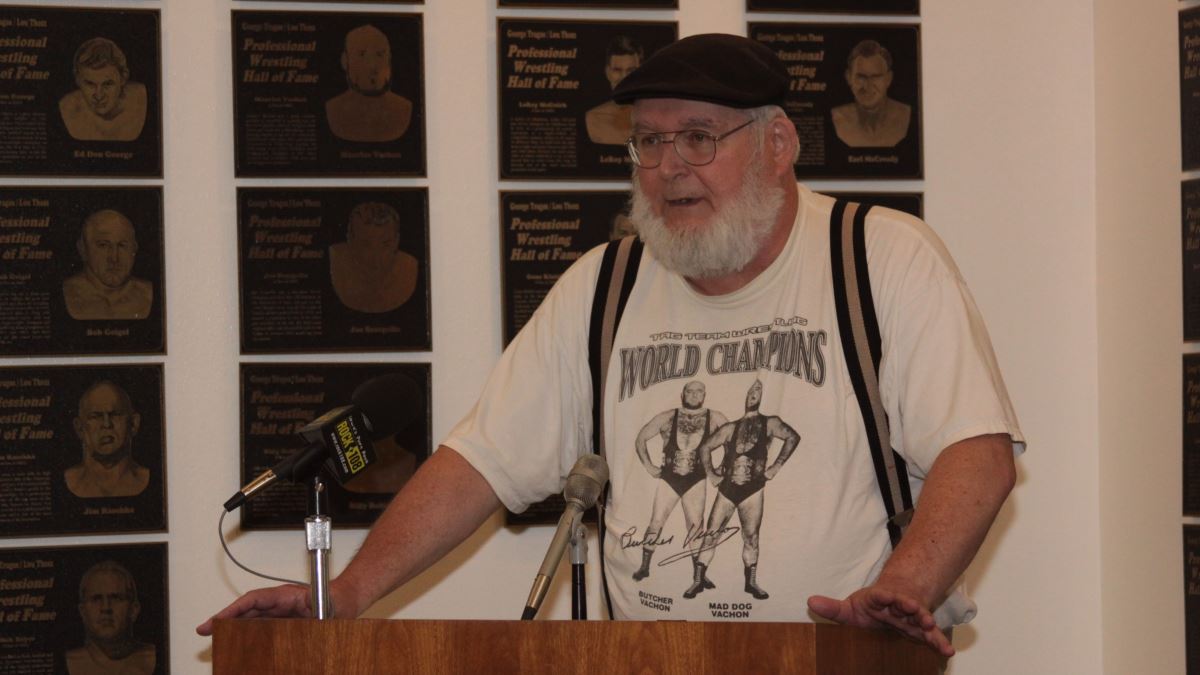

EDITOR’S NOTE: J Michael Kenyon is presenting this paper on the occasion of the annual George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame inductions at the National Wrestling Hall of Fame Dan Gable Museum, in Waterloo, Iowa. Kenyon will be receiving the James C. Melby Award this Saturday for his contributions to wrestling scholarship.

“Whatever deceives seems to exercise a kind of magical enchantment.”

— Plato, circa 350 B.C.

For more than a half-century following the U.S. Civil War, and despite repeated and consistent protestations the matches were “fake” and their results pre-determined, and despite repeated exposes in newspapers and magazines, those in the professional wrestling business never relented in the persistent claim their “sport” was as pure as the driven snow.

“Kayfabe” — a term thought to have originated in the carnivals where much of the “business” of pro wrestling also was developed — was an insiders’ way of insisting everything about the game was “real.” Faithful spectators, millions of them, contributed a willing suspension of disbelief.

Books about star wrestlers were written and published; books about “how to wrestle” proliferated. But professional wrestling, because its secrets were so closely guarded, never was the subject of a substantial history book. Not, at least, until Marcus Griffin, a New York City scandal sheet “sports editor,” authored Fall Guys: The Barnums of Bounce in 1937. This limited edition curiosity was subtitled “The Inside Story of the Wrestling Business, America’s Most Profitable and Best Organized Professional Sport.” When Scott Teal’s Crowbar Press reprinted it a few years ago, I wrote in the preface:

“In this day of ‘smart’ fans, where a variety of printed newsletters and internet-based fan forums routinely swap ‘inside’ info and speculate on the directions of the major promotions, it is hard to remember a time when ‘Kayfabe’ was a code of silence almost universally maintained by everyone in the business. What Griffin did in Fall Guys was to begin laying open the secrets of the mat game, and to explain how a group of dedicated entrepreneurs had built it from a now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t proposition popular only in isolated sections of the land to a big-bucks proposition that — inspired by the imagination and skill of Ed Lewis, and supplemented by the entry of a horde of popular footballers like Gus Sonnenberg, Joe Savoldi and Bronko Nagurski into its upper echelons — regularly began packing the largest arenas in North America with howling mobs of rassling-hungry customers.”

It’s safe to say, because, remember, this was a “sport” without a history, or “historians,” that the proverbial man-on-the-street had encountered few, if any, of these names. But they were the “dedicated entrepreneurs” who invented the multi-million-dollar charade known, largely, by its mildly pejorative phonetic abbreviation — rasslin’.By June 1938, Griffin — writing in Jack Dempsey’s new Sports Magazine — was revealing a “coast-to-coast network” of “mat masterminds.” Named were Paul Bowser, Billy Sandow, Tom Packs, Ed White, Joe (Toots) Mondt, Ray Fabiani, Rudy Dusek, Johnny Doyle, F.R. (Musty) Musgraves, Morris Sigel, Charlie Rentrop and Max Bauman.

But the combined literary works of Marcus Griffin didn’t sell well. World War Two came along and appeared to distract the populace, as did the rousing post-war economic “boom.” It took a post-war phenomena — television — to thrust professional wrestling into a national prominence it never before had experienced.

Along with the TV exposure came a few picture books, one constructed by New York City broadcast personality Guy LeBow; yet another by a former Associated Press sportswriter named Sid Feder. The latter filled up the spaces between the wrestlers’ photos with bits and pieces from thousands of promotional puff sheets — some of it actually true. His Wrestling Fan’s Book went through two printings in the early 1950s.

The televised wrestling furor died down, but not before it left a devoted coterie of new, young fans. Some started fan clubs for their mat idols; they, and many others, began subscribing to mimeographed “sheets” which told of wrestling shows from around the world. From this groundswell of interest evolved the first of what are now, loosely, called wrestling “historians.”

Basically, these mat buffs — a better way to describe them and so as not to offend those who have graduate degrees in the “discipline” of history — began reading both contemporary newspapers and past issues, and putting together accounts of where all the wrestlers were, and where they had been. It was discovered many wrestlers used different names when appearing in one region or another. A lot of them, probably to enhance the mystery of which Plato had spoken so many centuries before, wore masks. And, to preserve “kayfabe” when their masks were ripped off, many of them gave false identities.

Like movie stars, lots of grapplers used made-up names to begin with — and then, to shroud the fact they were on losing streaks (“jobbers” in the parlance of the trade), they continued to change their names. My particular passion, for 55 years, has been trying to straighten out all those monikers.

Always, keeping track of wrestling history was no easy chore, especially since the business — for at least another half-century following Griffin’s Fall Guys — continued to observe strict kayfabe. It’s only in the past 25 years or so that old wrestlers have begun telling stories on themselves — and some of them resolutely STILL refuse to break kayfabe.An inspiring milestone in books about wrestling spun off from a 1966 Sports Illustrated article by Joe Jares, whose wrestler-dad Frank was immortalized in “My Father The Thing.” Expanded into a solid history of wrestling in North America, it achieved instant cult status as Whatever Happened to Gorgeous George: The Blood and Ballyhoo of Professional Wrestling in 1974.

The electronic age, i.e., the computer age, opened up new vistas for examination. Today, there are hundreds of enthusiastic recruits to the hunt and who are busily pouring through Ancestry.com, NewspaperArchive.com, Social Security and passport records — every scrap of data available from which clues to all of wrestling’s “mysteries” might be obtained. Family members, especially during the second national TV wrestling “boom” of the 1980s and ’90s, poured forth with old scrapbooks filled with musty, mostly undated clippings and wanted to know if their dad, or uncle, or grandpa had been a famous wrestler. More clues were unearthed.

The U.S. Department of Justice did its best to help the cause, by amassing hundreds of documents and gobs of testimony in its antitrust probe of the wrestling business in the 1950s. Weldon T. Johnson and Jim Wilson, authors of the important Chokehold: Pro Wrestling’s Real Mayhem Outside the Ring, and Tim Hornbaker, who produced National Wrestling Alliance: The Untold Story of the Monopoly That Strangled Pro Wrestling, capitalized on extensive Freedom of Information searches. Other court-related transcripts have offered up scads of biographical detail heretofore unknown to curious ringsiders.

Bob Nitsche, whose day job for years was serving as business manager of a baseball team, the Reno Silver Sox of the California League, was the father of compiling “career” records of wrestlers. Upon his death, his seminal research — aided by a far-flung correspondent network and spanning 30 years — came to the “Godfather” of pro wrestling historians, Don Luce. No one man is any more active to this day — after a half-century of prowling through pro grappling’s past — than Luce. He and a fellow resident of New York state, former radio news editor Fred Hornby, have accumulated immense archives devoted to the game’s history over the past 60 years. Hornby tag-teamed with the research of Haruo Yamaguchi to produce the first full-bodied career record, that of “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers. At this nearly as long has been Tom Burke, who lives in a veritable wrestling “shrine” in Springfield, Mass., and produced, for many years, a very popular results sheet and Global Wrestling Nostalgia Sheets Nos. 1-45. He also published a still often-overlooked gem entitled Global Wrestling’s Yellow Pages of Wrestling in 1975.

The “sheets” have never gone away, dating all the way from H.A. Deaton (Fans Of The Mat) and William Wilson (Wrestling Results). The legendary Burt Ray cooked up a two-pronged “feast” of mat history in the 1960s, issuing a results sheet — MatMania — and captaining an old results-gathering club called Allsies. Ray also followed in Nitsche’s footsteps with more career compilations. Tom Gannon, who kept at it until he was in his 90s, was an Australian who set out to type, year by year, the results of EVERY professional wrestling card EVER held, anywhere in the world. A fellow Australian, and the son of an old wrestler himself, Libnan Ayoub, obtained the Gannon archive and continues in this mammoth vein. The mind-boggling European coverage of the late Gerhard Schaefer was a cornerstone of Gannon’s work.

Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of these appeared over the years, with the trend toward sophistication and — of concern to those kayfabe-cravers in the business itself — authenticity. By the early 1980s, a young fellow named Dave Meltzer emerged with the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, the first completely “smart” (non-kayfabe) sheet. Pro Wrestling Torch was a sturdy and long-lived imitation, and there were others, but WON, first a monthly, then a weekly, was the best. Meltzer, who began as a sportswriter, began writing mainstream newspaper columns. He became that same mainstream media world’s “go-to guy” whenever a pro wrestling story emerges. He has been writing sheets since 1971 and WON, full-time, since 1987.

All of this sort of thing, in the aforementioned computer age, began funneling into “chat” rooms and forums devoted to, among other things, discussing the history of professional wrestling. The unprecedented popularity of the game over the past 25 years, propelled by such pay-per-view extravaganzas as WrestleMania and Starrcade, also served to inspire myriad web pages devoted to regional and, in some cases, national histories. Newspapers, which for years had made fun of rasslin’, began offering weekly columns devoted to … rasslin’.

As kayfabe relaxed, wrestlers — and their fans — began attending “nostalgia” events. The Cauliflower Alley Club was the first to popularize reunions; they, in turn, led to halls of “fame” in Iowa and upstate New York and annual induction fetes.

Seemingly, scores of WWF-sponsored tracts have flooded the bookshelves, most notable among them Mick Foley’s Have A Nice Day and several sequels focusing on the personable headliner of the McMahon Era. Foley’s work regularly has made The New York Times‘ best-seller charts.An explosion of books about wrestling, many of them ghosted or co-written, began with Lou Thesz’ highly informative Hooker (Kit Bauman). Among the more notable efforts were Mark Hewitt’s Catch Wrestling: A Wild and Wooly Look at the Early Days of Pro Wrestling in America, and its sequel, Catch Wrestling Round Two. Greg Oliver and his writing partner, Steve Johnson, launched a Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame series which includes The Canadians, The Tag Teams, The Heels — with more to come. Ole Anderson, with Scott Teal, authored Inside Out: How Corporate America Destroyed Professional Wrestling. Likewise, Teal teamed with Joe Hamilton for Assassin: The Man Behind The Mask, an effort which featured no less than 278 photographs from the spectacular wrestling memorabilia collection of Chuck Thornton. And Terry Funk: More Than Just Hardcore was a collaborative effort with a newspaper writer, Scott Williams. Paul “The Butcher” Vachon‘s memoirs wear the title of When Wrestling Was Real.

|

Scott Teal, Greg Oliver and Chris Swisher. |

Two of the most prolific historians have been Scott Teal, whose Tennessee-based Crowbar Press has been churning out books and other compilations for nearly two decades. The influential Whatever Happened To … ? series, numbering Volumes 1 to 53, was followed by Shooting With the Legends #1. Steve Yohe of Montebello, Calif., has taken combining clippings with biographies and career details to an art form with his vast and relentlessly popular “Yohe Press” output, including prodigious career records, which go for as much as $100 on eBay.

Then came “mainstream” authors and important, exquisitely researched biographies, such as Gorgeous George: The Outrageous Bad-Boy Wrestler Who Created American Pop Culture (2008) and Jeffrey Leen’s bio of female wrestling icon Mildred Burke, The Queen of the Ring: Sex, Muscles, Diamonds, and the Making of an American Legend (2009).

Leen, in an interview with Greg Oliver’s SLAM! Wrestling internet site [Pulitzer Prize winning journalist turns attention to Mildred Burke in new book], revealed some of his methodology. “I learned as much as I could from the internet, from books, from old magazines in the Library of Congress, from online newspaper archives, and finally from Jack Pfefer’s archive at the University of Notre Dame. Pro wrestling gets no respect, and neither does pro wrestling research, but I was driven by the idea of treating the subject very seriously and respectfully, of doing my best to try to get to the truth of it and capture its flavor. A lot of amazing stuff has accumulated over the years about this little corner of Americana, and I tried to absorb and make use of all of that — Marcus Griffin’s book, Lou Thesz’s book … Steve Yohe on the internet, etc. Then I got (other) records: court, marriage, divorce, bankruptcy, property, incorporation, the Department of Justice antitrust case against the National Wrestling Alliance. Who knew that Mildred Burke owed Gorgeous George $3,000 in 1958?” Leen and Capouya were encouraged and assisted by the contributions of numerous mat “historians” referred to in this survey.

Speaking of which: Lou Thesz’ longtime Japanese agent, Koji Miyamoto, to encourage more interplay among them, formed an “International Pro-Wrestling Historians Club” in February of 2002, with 12 charter members. Among them was the late James C. Melby, whose name graces the award now presented during the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame weekend. The others were Luce, Hornby, Yohe, Teal, Hewitt, Ayoub, Burke, Yamaguchi, Thornton, Miyamoto and myself. Subsequent additions were Oliver, Johnson, Hornbaker and Dan Anderson who, at age 27, is the youngest of the group. A Wisconsin native, he specializes in late 19th-century mat history.

A short list of others who’ve made landmark contributions toward understanding what the saga of professional wrestling was all about: Louis Golmitz, Matt Farmer, Bob Leonard, Joe Svinth, Ed Garea, George Lentz, Will Morrisey, Vern May (a.k.a. Vance Nevada), George Rugg, Tony Vellano, Gary Will, Rich Tate, Hisaharu Tanabe, Ross Schneider, Mike Rodgers, Jim Zordani, Tim Dills, Graham Cawthon, Brad Dykens, Jason Campbell, Nathan Hatton, Matt Buziak, Dave Cameron, Jim Craig, Ron Dobratz, Don Laible, John Pantozzi, Mike Smith, David Williamson, Karl Stern, Mike Tenay, John Williams, Steve Sims, Dick Bourne, David Chappell, Dr. Mike Lano, Mike Mooneyham, Evan Ginzburg, George Schire, Daniel Chernau and Mike Chapman.

The inaugural James C. Melby Award was presented to Melby at the 2006 George Tragos/Lou Thesz Hall of Fame induction banquet. The award was created to recognize a journalist or historian who has advanced professional wrestling through his or her writing.

Few, if any, have taken the analytic, record-oriented approach to wrestling history that Jim did. A member of the Cauliflower Alley Club board, and intimately associated with the business going back to his early days in the ‘60s with program/magazine publisher Norman H. Kietzer, Melby produced dozens of fact-filled issues of Wrestling Facts over the years, many of them detailing the careers of mat legends, others filled with clips from a bygone era. And he capped his endeavors with a charming memoir, Gopherland Grappling: The Early Years.

“It has always been important to me to apply the high journalistic standards that I had been taught in college,” said Melby after being presented his namesake award. “History is important and should be accurately documented, and once it is committed to print that it belongs to everyone.”

TOP PHOTO: J Michael Kenyon at the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame. Photo by Wayne Palmer

RELATED LINKS

- February 12, 2009: Examining the art of pro wrestling journalism

- National Wrestling Hall of Fame Dan Gable Museum

- Duff Johnson’s commendably comprehensive bibliography of pro wrestling history books may be found at his delightful and absorbing www.houseofdeception.com web site.