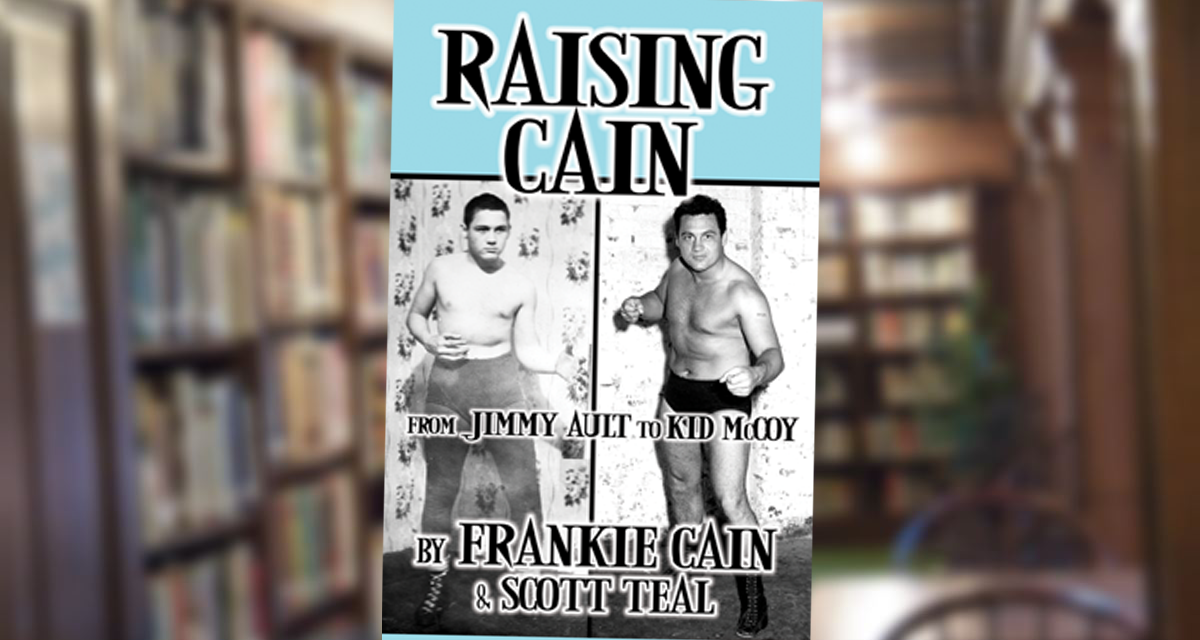

Things have come a long ways since Lou Thesz, arguably the greatest heavyweight champion who ever lived, had to self-publish the original edition of Hooker because it was felt that there was not a sufficient audience for wrestling autobiographies. A quarter century later, wrestling autobiographies flood the market. Virtually everyone appears to be getting their story in print, including performers whose time in the business, in contrast to Thesz, was little more than a fleeting moment in their own lives, and less than a fleeting moment in the broader expanse of wrestling history. With Raising Cain: From Jimmy Ault to Kid McCoy, the process comes full-circle, telling the life story of a person whose involvement in not only wrestling, but the broader world of North American combat sports, stretches from the Great Depression to the cable television era. It is not an exaggeration to state that Ault, best known by the name Frankie Cain, is the single greatest repository of living knowledge on North American professional wrestling: a fact vividly illuminated by this first volume of his recently-published memoir from Crowbar Press.

Jimmy Ault aka Frankie Cain in 1960. All story photos contributed by Scott Teal.

Although ostensibly a “wrestling memoir,” Raising Cain is really a long form interview between Ault and Crowbar Press publisher Scott Teal. It is also as much a story of survival against overwhelming odds as it is a tale of ring exploits. In contrast to the vivid recollections of his childhood, Ault’s very earliest life, including precise age and parental origin, is a mystery. By the age of six or seven, he was essentially living on the streets. A lack of any significant formal education, coupled with a heavy speech impediment, magnified the challenges already faced by Ault as he grew up on the boulevards and in the bordellos of Depression-era Columbus, Ohio. In addition to the ostensibly-legitimate enterprise of shining shoes, young Ault carved out a living, and a reputation, on the streets of Columbus, by running innumerable hustles and engaging in near-daily alley fights, accompanied along the way by a colourful cast of characters including the broad-shouldered and charming Django Moleno, the prodigal shoeless kid-turned attorney, Gabe Kaplan, and various members of the local Romany community who adopted him into their ranks. As they follow him from roof tops, to brothels, to pinball arcades, readers are not just given vague recollections, but precise details, on how the hustles were orchestrated by Ault and his evolving cadre of collaborators.

Ault’s immersion into the wrestling business began after he attended his first card in 1938. Inspired by the pros, he helped found the Toehold Club, where youths, frequently from impoverished backgrounds, would get together and mimic the skills of those in the paid ranks. In addition to wrestling on a near daily basis at the Toehold Club, he would hang around the office of local promoter Al Haft and the 20th Century Gym. By the age of 12, Ault was already capturing the interest of prominent visiting professionals, as well as the local press, for his precocious grappling talent.

Although far more than a “wrestling story,” Raising Cain nevertheless excels, and even carves out significant new ground, in four distinct, but related, areas: through its examinations of shooters and shooting matches in professional wrestling, the seedy and violent realm of ‘smoker’ fighting, traveling Carnival AT (athletic) shows, and the nebulously legitimate world of journeyman prizefighting. For SlamWrestling.net readers, the first and third elements of Ault’s tale are likely of greatest interest.

Ault boxing in 1950.

Beginning with the publication of the aforementioned Hooker, readers were given a glimpse into the ‘legitimate’ side of professional wrestling training, as Thesz honed his craft in submission wrestling, or hooking, under the stern supervision of George Tragos. In Ault’s tale, Frank Wolfe’s role in Columbus parallels that of Tragos’ in St. Louis as a relatively obscure, but nevertheless deadly, purveyor of wrestling knowledge. Outside of Raising Cain, information on Wolfe has, until now, been difficult to come by. Yet, as one of only a tiny handful of people that Karl Gotch ever paid glowing tribute to for his abilities, there is little doubt that readers interested in the toughest-of-the-tough men in wrestling history will be keenly drawn to Ault’s recollections of Wolfe. Outside of Wolfe, Ault also weighs in on the ‘shooting’ abilities of other wrestlers, how they stack up against one another, and recalls the legitimate workout matches and contests he witnessed. Far more than Thesz, Ault also goes into technical detail on some of the ‘shooting’ moves he mastered. Admittedly, such minutiae might be lost on many wrestling fans, but for those with a bit of background knowledge of wrestling, Ault’s comments represent some of the last surviving technical commentary on a completely bygone era of wrestling and fighting history.

The legitimate wrestling skills learned under Wolfe’s tutelage stood Ault in good stead when he transitioned to working on the carnivals. There, he faced numerous challengers in legitimate contests. Carnival wrestling probably received its most mainstream autobiographical exposure in Kirk Douglas’ Ragman’s Son (1988), and outside of a few scattered lines in works such as Harley Race’s painfully-short King of the Ring, the interviews conducted by Teal with Billy Wicks and Dick Cardinal in the Whatever Happened To…? news magazine represented, to date, the most in-depth examination of the subject. Ault’s recollections both reinforce, and add to, those already offered by Wicks and Cardinal. More than the aforementioned interviewees, he also takes the reader off the bally, and away from the ring, to look a bit more broadly at traveling carnival businesses. Ault’s reminiscences of the carnival wrestling days are remarkable, and in this reviewer’s mind, warrant an even deeper examination with regard to the details around specific matches and how he dispatched his opponents.

More than virtually any autobiography, Raising Cain takes readers to the grey zone between ‘shoot’ and ‘work’ in not only wrestling, but the broader world of mid 20th century combat sports. Anyone wedded to the binary notion that all pro wrestling was always and at all times a work, will be forced to expand their horizons on the subject. Additionally, fans of boxing history will come to appreciate how, especially at the journeyman-level, boxing also frequently straddled its own line between contest and collaboration.

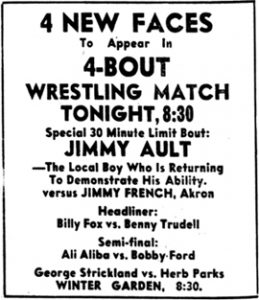

A 1948 wrestling advertisement from Chillicothe, Ohio featuring Ault.

Raising Cain covers approximately 25 years of history and represents Ault’s life before he ‘made it’ in the world of big-time professional wrestling as Frankie Cain and the Great Mephisto. Along the way, he introduces us to innumerable figures he met on the early stages of his journey, in a narrative style that evokes occasional pathos, frequent humour, and continual astonishment in the reader. Running through it all is the persistent thread of how a young man’s life hustling in the street, while simultaneously bouncing in and out of professional wrestling, worked synergistically to produce one of the finest minds for finishes and angles ever seen in the business. Undoubtedly, this outcome will be fleshed out in further depth in the forthcoming second volume of Ault’s tale.

Since Raising Cain is not a standard autobiography, but a long form interview, it lacks some of the same narrative flow of a standard (and usually ghostwritten), memoir. At times, it is a bit difficult to get a bead on the exact chronology of events in relation to one another. Some readers may prefer a more conventional format. Yet, as a long-form interview, it is extremely well done. As A.M.J. Hyatt once noted in Oral History Forum, “it is as professionally undesirable to turn an uninformed questioner loose among potentially important subjects as it is to excavate a burial mound with a back hoe.” Hyatt can rest easy with Teal’s work, which bares constant evidence of diligent research on every element of his subject matter’s public life—a point even made by Ault himself at various intervals.

In summary, Raising Cain is essential reading for wrestling fans, but also for boxing fans. Far from retreading old ground, Ault’s story stands like a beacon of light in a congested genre, illuminating aspects of the wrestling business—and in fact the broader world of North American combat sports—in ways that have never before been exposed to public view. It is one of the most significant works of its kind ever produced.

Scott Teal.

RELATED LINKS

- Buy Raising Cain: From Jimmy Ault to Kid McCoy from Crowbar Press

- Scott Teal: Twitter and Facebook

- SlamWrestling Master Book List

PREVIOUS CROWBAR PRESS BOOK STORIES ON SLAM

- November 10, 2020: Time to strut; biography on Buddy Rogers announced

- October 23, 2020: Rikidozan Years fills a void in a “gaijin’s” understanding of Japanese wrestling

- June 17, 2019: Breznikov’s book comes from the heart of a fan

- February 24, 2019: Guest column: My passion for Bruiser Brody has never waned

- June 11, 2017: Guest column: The story behind “Battleground Valhalla”

- February 25, 2017: Dinner with the legends turns into a book

- June 17, 2016: Fleming’s take on wrestling makes for a great read

- January 4, 2016: Teal’s “Classic 20th Century Mat Memories” interviews truly marvelous

- September 5, 2015: Don Fargo lets it all hang out in “The Hard Way”

- September 29, 2013: Insight into Japan one great part of Stan Hansen book

- August 23, 2013: Brisco book reprinted, reworked

- March 4, 2013: Missouri belt book a labour of love

- December 30, 2010: Atlas blames no one but himself in autobiography

- March 2, 2010: Hard-to-find Drawing Heat book back in print

- February 11, 2010: Wrestling in the Canadian West a rich and fascinating book

Truly a review worthy of the subject. This book was a page-turner in a way not often seen in this genre. I was riveted to Cain’s story, but also sad when it was over that I would have to wait nearly a year for volume 2. This book is a perfect example of how important it is to document the stories of people like Frankie Cain while they are still around, as so many of his stories can’t be found in newspapers or even the memories of others who knew him along the way.