You’d be hard-pressed to name a better guy, in and out of the ring, than Abe Jacobs. An old-fashioned babyface who could mix it up with the best of them, Jacobs was a mainstay of the Mid-Atlantic promotion during a pro career that lasted a quarter-century and produced memories that will linger even longer.

Like the time the master of the Kiwi Roll was wrestling the relentless Danny Hodge, an occasional tag team partner, in the Northwest. A fan brought a pet monkey to ringside and, while Hodge was petting it, the primate decided it was an ideal time to go to the bathroom on the wrestler’s shoulder.

“Danny gets mad, but he really got mad that night. They washed him off, and I’m up in the ring waiting for him. I said, ‘Holy moly, this is going to be a tough night tonight,’” Jacobs recalled with a laugh.

“I’d heard that he knew over 10,000 moves, and I saw every one of them in the first five minutes. Anyway, he gave me a little daylight, and I called the referee over to my face. I said, ‘Help, Mr. Hodge, Mr. Hodge. Look, I didn’t do it! It was that son-of-a-gun of a monkey that did it!’”

That kind of goodwill brought Jacobs respect from so many of his contemporaries. He died Monday, August 21, 2023 at the University Place Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Charlotte, N.C., after several years of declining health. He was 95.

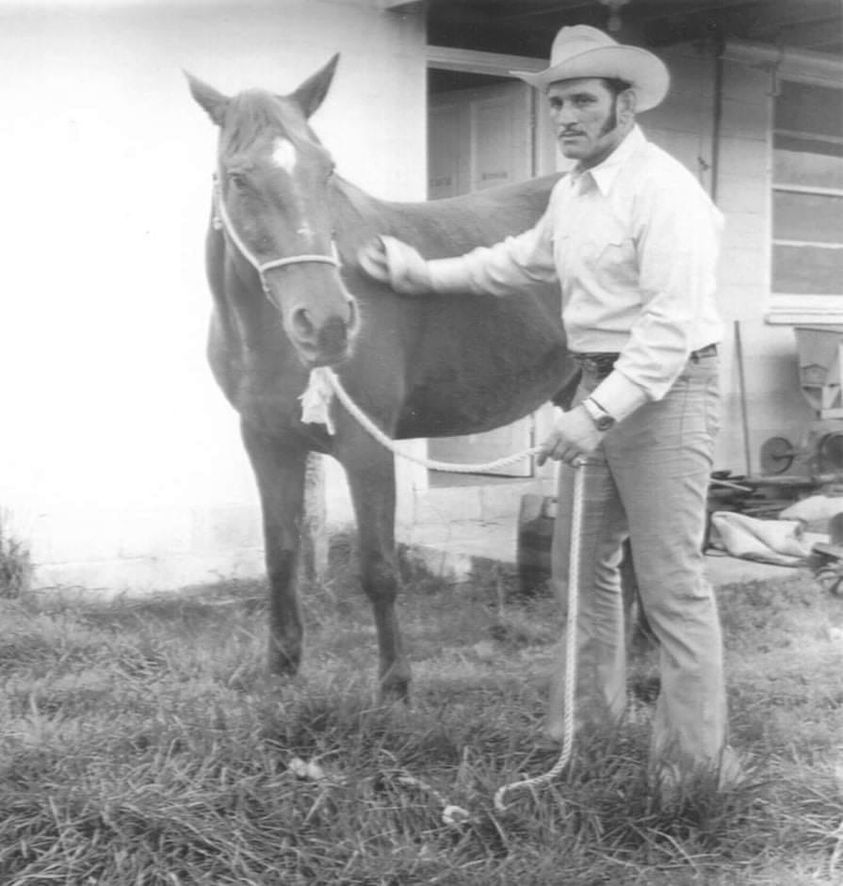

“Abe was an excellent athlete and a very skilled mat wrestler,” said wrestling guru Les Thatcher. “Easy to travel with and a guy who could have a good match with anyone. I always felt he should have been pushed more. The only things he may have loved as much as wrestling would be his golf game and his horse.”

As the New Zealander once explained to journalist Mike Mooneyham, “Wrestling has been my life,” says Jacobs. “It’s what I wanted to do as a kid. I started when I was 10 years old in school.”

LEARNING THE ROPES

It was a half-a-world journey for Jacobs from his birthplace in the ocean-locked Chatham Islands, about 500 miles off the coast of New Zealand, to Waterloo, Iowa, where he was inducted into the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2008.

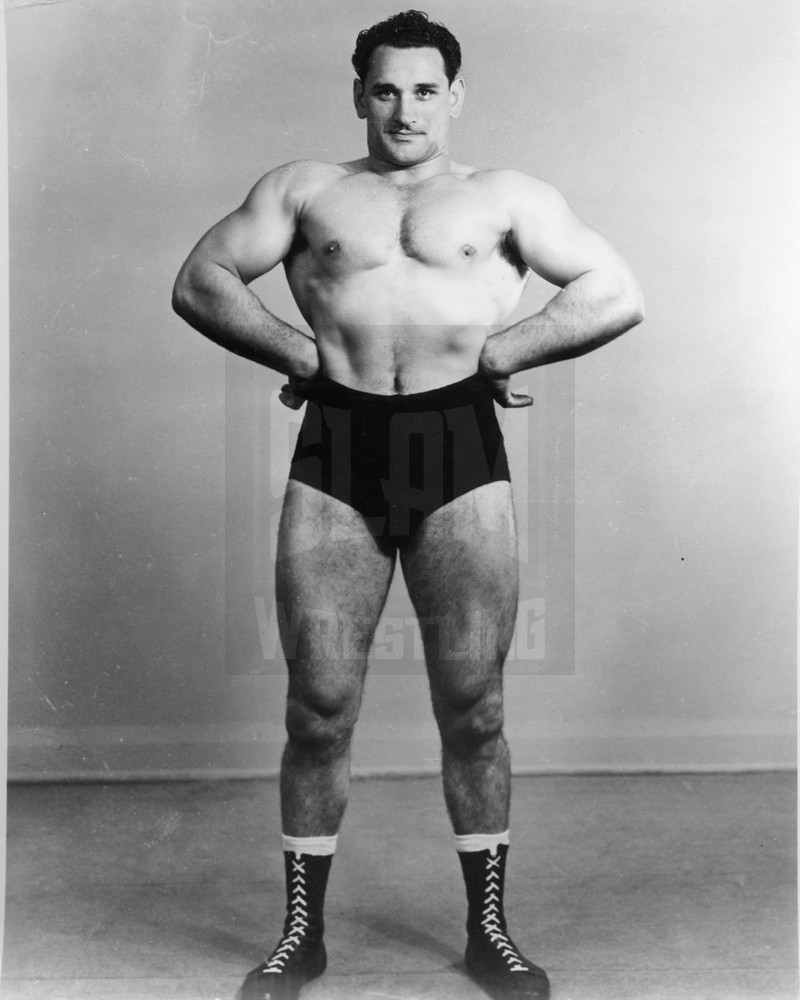

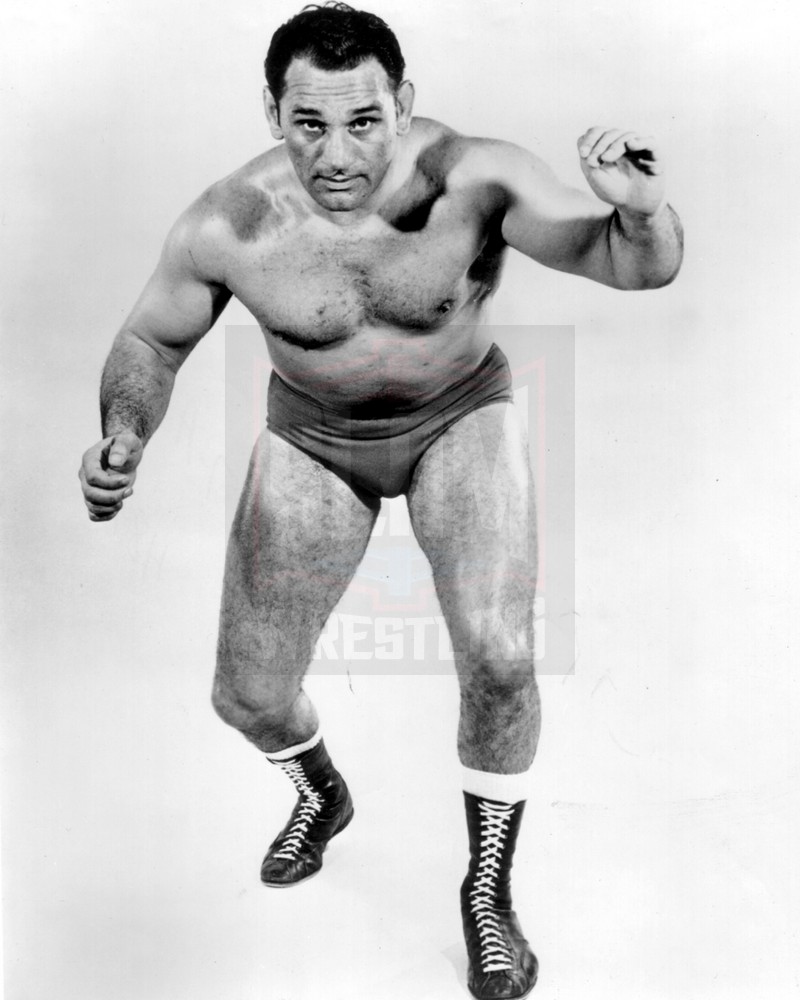

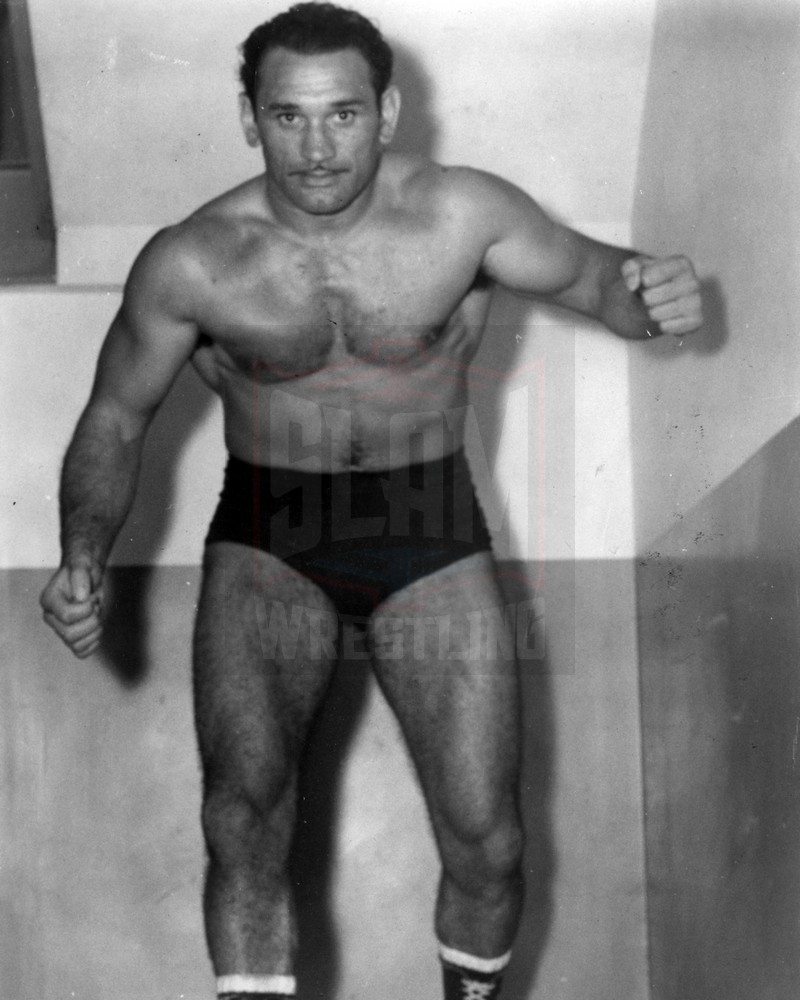

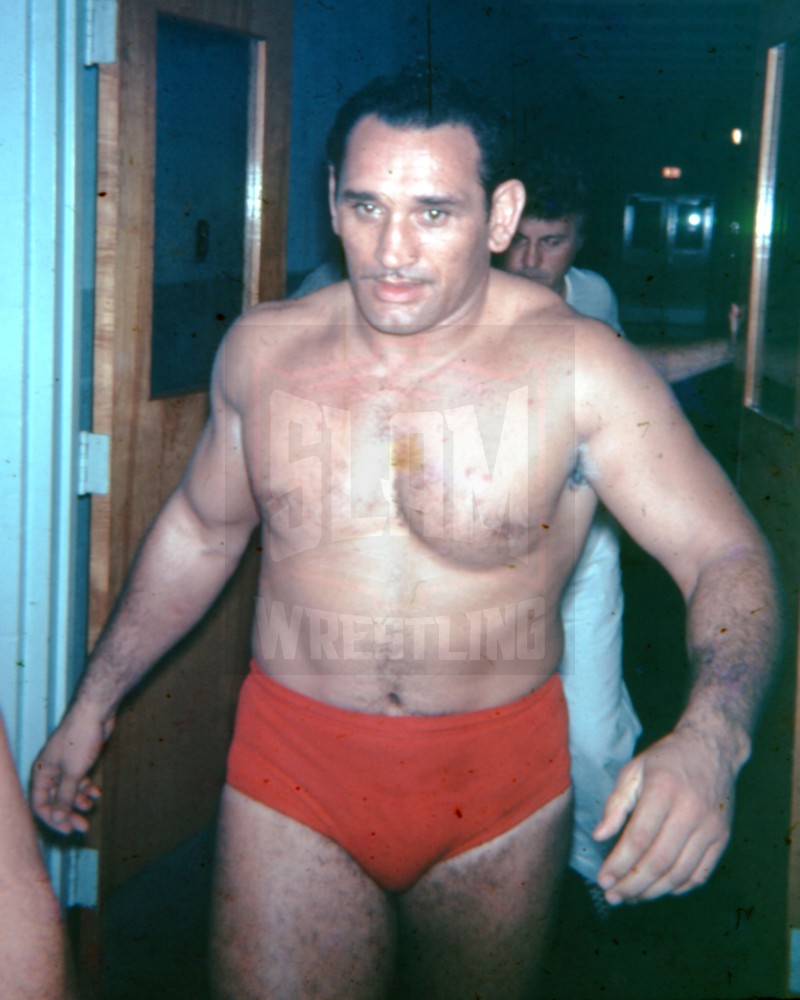

Abe Jacobs in 1974 in a Mid-Atlantic Wrestling calendar.

And not just in terms of travel. His living conditions spanned the globe, too. Jacobs grew up on a ranch of about 6,000 cattle and 2,000 sheep, and rode horseback to school since there were no roads to speak of. At 13, he spent three days taking a herd of 1,200 sheep a mile long over land. “I was riding a horse, and you had to go uphill at times. … You had dogs ahead and bringing up the rear. Those sheep dogs really do some work,” he told the Mid-Atlantic Gateway.

Back indoors, he started to listen to radio broadcasts of wrestling matches and decided to start wrestling with men, rather than livestock. At 15, he headed to the mainland of New Zealand, where he encountered an entirely different lifestyle. “It was hard to find your way around because I had never been in a city. I had to learn to ride a bike, and then I had to learn the rules of the road. And when you were used to being on a horse, there were no rules of the road there.”

He filled out and quickly became a highly regarded amateur, winning multiple provincial titles and participating in the 1956 Olympic trials. His success was enough to prompt him to enter the pro ranks with the help of George (The Zebra Kid) Bollas and Jim LaRock, a pair of fine amateurs-turned-pro. The link between amateur and pro in New Zealand was less stark than it is now, Jacobs recalled, as a typical card would have six or seven amateur matches and one or two pro bouts contested in 8-minute rounds.

“Jim Larock … he was a great amateur wrestler. I believe he was an alternate for the 1952 Olympics — he was actually an alternate for the U.S. team. He was a great wrestler and I knew this … and when he came out I was still over [in New Zealand ] as an amateur, and I worked out with him and the other guys I’ve mentioned,” he said to the Gateway project.

WORLD TRAVEL

In 1958, the New Zealand Wrestling Union gave him a start as a professional in Hastings, as a substitute for George McKay, as he faced his friend, The Zebra Kid. After about a dozen matches, he headed to Hawaii later that year, billed as New Zealand champion and of Jewish, Maori, German, Portuguese and American descent.

He beat Jerry Gordet with a bearhug in 15 minutes and went on to defeat Charlie Kalani, later known as Prof. Toru Tanaka, in his next bout.

After a couple of months of seasoning, he headed east to Capitol Wrestling in late January 1959, becoming a popular fixture on Tuesday night cards in Baltimore, and wrestling on the undercard at Madison Square Garden. Johnny Valentine became a hated foe; twice tossing sand into Jacobs’ eyes to cost him matches at the Baltimore Coliseum. The two would feud dozens of times for years in different parts of the country.

After meeting Jacobs in 1959, Pennsylvania sportswriter Bob Vosburg was impressed and may have gotten Jacobs’s age correct for once. “He’s a tall, dark haired, raw-boned 230 pounds with a most dignified manner of speaking. A native of New Zealand, Abe is 26 years old and talks about wrestling almost as if he were a fan rather than a performer.”

But Jacobs made it clear that the dignified business went out the window once challenged in the ring. “In amateur wrestling,” he told Vosburg, “you can take a man’s arm behind his back only so far, but in pro wrestling you can break it off.”

Advertised as the Jewish champion to appeal to ethnic fans, Jacobs had a strong run in the Capitol Wrestling promotion against the likes of The Sheik, Jack Terry, Angelo Savoldi and the Zebra Kid for a solid year before moving to the Michigan and Ontario circuits in 1960. While in Canada, he won a version of the North American junior heavyweight championship, his first belt, knocking off Kurt von Stroheim in August 1960 for promoter Larry Kasaboski.

He returned east later that year and stayed through May 1961, when he made his first appearances in the Mid-Atlantic territory that he would call home. Breaking in against the likes of Tinker Todd and Johnny Heidemann, he rose to the top of the card to earn a series of matches with Buddy Rogers, one occurring just four days before Rogers lifted the NWA world heavyweight title from Pat O’Connor in Chicago.

Jacobs recalled that the original “Nature Boy” was easy to work with, but was more showman than grappler and had a bad streak inside the ring. “He tried to hurt me the last time we wrestled, which was in Norfolk,” Jacobs recalled. “Buddy was a great man for himself. What he had was a bunch of friends that always thought he was the greatest in the world. He had about four or five guys. What he would do, he would go into a territory, get with the booker or the promoter, he’d tell them, ‘Hey, I’ll make you some money, blah, blah, blah, do this, do that.’”

Jim Crockett Sr.’s Carolina-based promotion loved tag team wrestling, and Jacobs soon found himself in main and semi-main events paired with Chief Big Heart and veteran George Becker. Interestingly, Jacobs never held a title belt in the Carolinas, even though he’d be there for the better part of two decades. In later years, he reflected that those were reserved for Becker and Johnny Weaver, or the Scott Brothers, although Jacobs won several championships outside of Crockett territory.

“Yes, they had those guys you spoke of, and nobody was going to get anywhere beyond them,” he once told Mid-Atlantic Gateway interviewers. “I liked [Crockett’s] area, but it got frustrating at times. But that’s the nature of the beast. I did all right when I was here, but actually, I did very well when I was out of the country. Like when I was in Europe, South America and the Far East.”

One story will suffice to demonstrate that Jacobs was never going to break the Becker-Weaver glass ceiling. In 1972, Luther Lindsay died in the ring in Charlotte, N.C., of a heart attack. Lindsay was one of the great wrestlers of his era, and a close friend and tag team partner with Jacobs, who was in the next match.

A few days later, Lindsay’s widow called Jacobs and asked him to help pick the pallbearers. She called the Mid-Atlantic office to tell them that she had reached out to Jacobs. Crockett, Becker and Weaver were the office bigwigs, and Becker and Weaver insisted on being pallbearers.

Crockett then called Jacobs to convince him that the territory’s top stars should be pallbearers. “It looked like a political deal to be pallbearers for Luther’s funeral,” Jacobs recounted, adding that it wasn’t until about 30 years later that he visited Mrs. Lindsay and told her the story.

THE KIWI ROLL

Mooneyham once observed that if ever one hold were more closely associated with a professional wrestler, “the Kiwi Roll and Abe Jacobs would be right at the top of the list.” Jacobs said he developed the maneuver as an amateur experimenting in a gym, laying his leg into the bend of an opponent’s knee, keeping pressure on the ankle, and rolling his rival into submission. It’s rarely been copied, but, like the figure-four leglock, it can cause a lot of pain.

“There are a lot of people now that still ask me about the Kiwi Roll,” Jacobs told the Gateway project a few years ago. “People will say, ‘What’s your name?’ I’ll say, ‘Abe Jacobs,’ and they’ll have this blank look on their faces. Then I’ll say, ‘Do you remember a guy who used to do the Kiwi Roll?’ They’ll always say, ‘Yeah!’ So they remember the hold, even if they don’t remember me.”

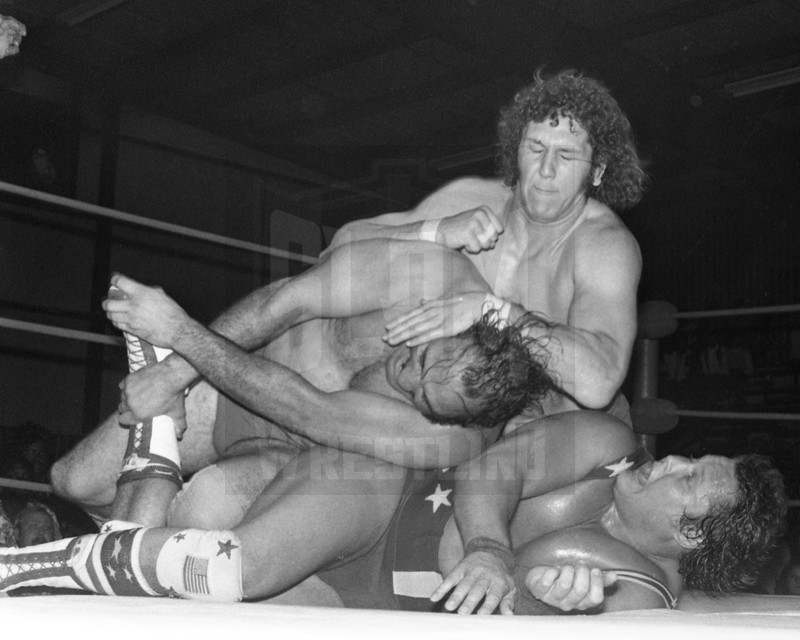

Yet even though Jacobs could handle just about anybody in the ring, he understood his role including using his skills to boost other wrestlers. There was no better example of that than his tag team with Haystacks Calhoun, billed at 600 pounds, though Jacobs put him closer to 400-plus. They met in the Carolinas and then headed to Los Angeles, where they briefly held the International TV Tag Team Title in 1962 before losing it to The Destroyer and Don Manoukian.

“Haystacks never went off his feet and you had to work around him. When I was his partner, I got in terrific shape because I did all the work. And you had to know how to handle a big guy like that,” Jacobs said.

“They’d work the hell out of me and I’d get a hot tag in to him. But then he’d come in, and, of course, that was what the people wanted, he’d clean house, boom, boom, boom,” he said. “He could get through those ropes pretty good for a big guy. He’d get in in a hurry, but, of course, like all big guys, two or three minutes, and he’s all blown up just like a sumo wrestler.”

Jacobs also held the Florida version of the world tag team title with Don Curtis in 1964, and the Western States tag team title with Pez Whatley in 1976, a year in which he also wrestled as the Red Pimpernel during one of his many tours of Japan.

Later in his career, Jacobs went in the ring with untested rookies to show them the ropes. Barry Windham had his first match with Abe Jacobs in the Carolinas and it was “a stinkeroo. I think it went about eight minutes and Abe beat me with a slam; that tells you how good it was,” Windham laughed. “Abe trained all the guys and helped train me. It was part of the learning experience being in the ring with Abe.”

Before Charlie Fulton died in 2016, he remembered that Jacobs treated him “like a million bucks. … He always took care of me and took me to school in the ring and never hurt me. He taught me a lot of things on the go and it was like on-the-job training.”

RETIREMENT

After hanging up the boots in 1983, Jacobs went to help manage Ricky Steamboat’s gym in Charlotte, worked as a shuttle bus driver at the Charlotte airport, and played tons of golf to the point that he had a business card advertising his availability for charity events. His participation helped to raise money for the North Carolina-based Eblen Charities. “If Abe Jacobs isn’t in a class by himself, it certainly doesn’t take long to call the roll,” said Bill Murdock, executive director of the organization.

Golf also was the vehicle for Jacobs to find his wife, Evelyn, widowed from ex-wrestler John Smith. At the behest of her late husband, she went to a local golf course, knowing it was one of Jacobs’ haunts. She bought him a dozen golf balls and things bloomed from there. They were together from 1985 until his death and were married in 2000.

“Nobody gets anywhere in this world without help. I’ve had a lot of help along the way,” Jacobs said at his induction into the Tragos/Thesz Hall of Fame. “Could you picture a world without wrestling? I can’t.”

In addition to his parents, he was preceded in death by his sister, Dolly Nielson. Those left to cherish his memory include his wife, Evelyn Murray Jacobs and her sons, Reggie Hammond (Joyce) and Richard Hammond all of Tampa, Florida; sister-in-law, Mae Stevens (Ronnie) of Rutherfordton; special friends, Christine Flores of Charlotte and Kim Thompson (A.D.) of Forest City and renowned sportswriter, Mike Mooneyham of Charleston, SC. The funeral services will be conducted at 1:00 pm on Tuesday, August 29, 2023 at the Harrelson Funeral Chapel. The family will receive friends from 6:00 until 8:00 pm on Monday at the funeral home. Burial will take place in New Zealand on a later date.

ABE JACOBS GALLERY

ABE JACOBS STORIES

- Jan. 24, 2022: Mat Matters: An appreciation for the wonderful Abe Jacobs

- June 28, 2008: Piper, Saito, Jacobs enter Tragos/Thesz HOF

- Dec. 13, 2007: Abe Jacobs’s fantastic wrestling voyage