Try as they might, the world title bouts at WrestleMania in Chicago on April 2 will forever pale in comparison to the world title change that took place at Comiskey Park on June 30, 1961. It was a turning point in wrestling history, with the legitimacy of the champion giving way to the headstrong showman, and the genesis of what would become the WWWF.

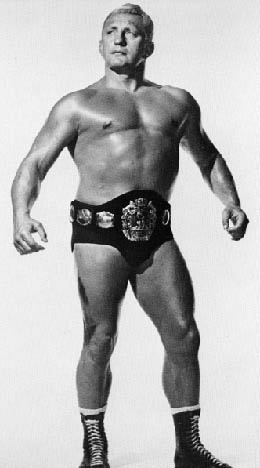

“Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers

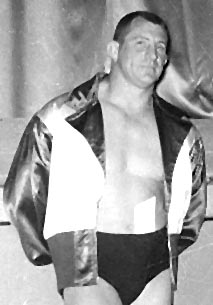

On that summer evening in the home of baseball’s Chicago White Sox, Pat O’Connor entered the ring to defend the NWA World Heavyweight Championship against “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers.

O’Connor was an amateur wrestling champion from New Zealand, and represented his country in the Pan-American Games in 1948 and the British Empire Games in 1950. In North America, he made his way up the ranks with determination after training with Len Levy.

“Pat was a true main-eventer from the time he came from New Zealand,” St. Louis promoter Larry Matysik said when O’Connor died in 1990. “Pat wasn’t really a big man but he was a real athlete with a very smooth and fluid style. He was a great crowd pleaser.”

O’Connor would claim the NWA world title after defeating Dick Hutton at Kiel Auditorium in St. Louis on January 9, 1959. “Pat was good. You had to be a heel with Pat, though. He was a babyface. He wouldn’t heel for anything,” Dick Hutton said in a 2000 interview with Whatever Happened To …?

Rogers had been wrestling since 1939, working as Dutch Rhode while still a police officer in New Jersey. After taking the “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers moniker in Texas, his career took off. When wrestling entered living rooms via the Dumont Network, Rogers became one of the biggest names in sports. Working primarily out of Columbus, Ohio for years, booked by promoter Al Haft, Rogers was a regular in Chicago and routinely sold-out the International Amphitheater.

The match drew a staggering 38,622 fans, a record for attendance that stood for pro wrestling in North America for many years, until WrestleMania III in 1987 topped them all. The ticket sales of $148,000 would remain a pro wrestling record for nearly two decades. (And like WrestleMania III, the attendance number was widely worked, and Rogers in a Wrestling World interview in December 1963 claimed it was 41,000.)

Fortunately, a tape of the match still exists, and has even been broadcast during recent years on ESPN Classics’ Golden Age of Wrestling. Billed as “The Match of the Century,” it was a two-out-of-three falls affair, with a one hour time limit. At ringside was Rogers’ manager Bobby Davis, though he doesn’t factor at all in the match.

In the first fall, Rogers scored the pin in eight minutes when he caught a charging O’Connor with a knee lift in the corner. In the second, O’Connor took control with a series of headlocks and punches, and rolled Rogers up with a reverse cradle after six minutes.

The heat for the third fall built throughout the stadium, and it looked as if O’Connor would retain his title, manhandling Rogers for much of the fall. The New Zealander went for a dropkick, but missed, landing on his head. He rolled around the ring, holding his ribs. The Nature Boy jumped at the opportunity and covered O’Connor for the pin after seven minutes.

“Even though it was outdoors the roar of the crowd was so bad at times that we couldn’t hear the referee,” O’Connor is quoted as saying in the May 1964 edition of Wrestling Confidential. “I’d get a good hold on Rogers and start twisting, but even thought I could see his mouth open and that he was in pain, I couldn’t hear him yell.”

After the match, Chicago promoter Fred Kohler entered the ring and presented Rogers with the NWA title. The villain thanked the promoter, and bragged “To a nicer guy it couldn’t happen.”

The historical impact of the title change is one thing, but the backstage goings-on are all the more relevant today. Kohler had been one of the most successful promoters in history, and Chicago was a key city during the 1950s on the wrestling map. After Sam Muchnick left the NWA Presidency in 1960, Toronto promoter Frank Tunney took over and Kohler arranged for the title switch. Then in 1961, Kohler ascended to the NWA Presidency, though he wouldn’t last, either as president or as a promoter in the 1960s.

Pat O’Connor. Photo by Terry Dart

Kohler had a key partner in his promotion by that point — Vince James McMahon (Vince Sr.), and his Capitol Wrestling Corporation. Buddy Rogers had been a long-time favorite of McMahon’s, and he was a regular on the promotion’s northeastern United States circuit.

“It was a major title change. It also put Vince McMahon on the map so far as the midwest was concerned. The handouts and whatnot contained McMahon’s name as Rogers’ manager,” said historian Fred Hornby, who compiled the Buddy Rogers Record Book. “That was pretty much McMahon’s baby.”

Compared to the men with legitimate backgrounds who had preceded him — O’Connor, Hutton, Lou Thesz — Rogers was a showman through and through, albeit perhaps the greatest heel ever. His arrogance wasn’t an act.

“The shooters hated him because here was Buddy, no wrestling ability, yet he’s in the main event and they’re not. It all comes down to performance,” explained Dick Hutton in a 2001 interview with Wrestling Perspective. Lou Thesz concurred, in his chat with SLAM! Wrestling, when asked about Rogers. “Not a wrestler. A great show person. As far as real wrestling, forget it.”

“Some heels in life are almost so good at what they do, you can’t help but admire them,” wrote Bobby Heenan in his book Chair Shots and Other Obstacles, saying that Rogers “was truly one of those heels in life who was a backstabber, but he was so good at it and really smooth. I’m not proud of it, but part of me admired what he did. Anyone would, as long as they were not on the receiving end of what Rogers did. He was smart and knew every backstabbing way to get himself over in the ring.”

As the NWA champ, Rogers drifted out of the promotion’s traditional control and took many more northeastern United States bookings than previous champs, influenced in large part by the bright lights of New York and the charm of McMahon. (He only had one rematch with O’Connor as well, on September 1, 1961 at Comiskey Park, which was won in three falls by Rogers.)

“[McMahon] almost put [Rogers] entirely in the northeast for his entire title run with the NWA title. That’s what got the other promoters hot and bothered,” said Hornby. “The only places Rogers would really go would be Texas, because he still had an allegiance with Paul Boesch and Morris Sigel, and he would go out to the Pacific Northwest for Don Owen.”

Things began to spiral out of control with Rogers, and on August 31, 1962 in Columbus, Ohio, the Nature Boy was injured in a locker room confrontation with wrestlers Karl Gotch and Bill Miller. The decision was made to get the belt away from him, and a 47-year-old Lou Thesz would capture his sixth NWA title on January 24, 1963, in Toronto.

McMahon’s Capitol Wrestling Corporation refused to recognize the title change, protesting that it was just a one-fall affair, and continued to recognize Rogers as world champion, complete with claiming Rogers won a fictitious tournament. Then, on May 17, 1963, Rogers dropped the newly-created WWWF world title to Bruno Sammartino in a mere 48 seconds.

The Windy City of Chicago would have other title changes over the years — notably the Ric Flair versus Ricky Steamboat battle at Chi-Town Rumble on February 20, 1989 — but none would ever compare to O’Connor-Rogers. The matches on Sunday, April 2nd at WrestleMania 22 may be more complicatedly booked (Triple H vs John Cena) or filled with more highspots and action (Kurt Angle vs Rey Mysterio vs Randy Orton), but they can’t possibly measure up.

MORE BUDDY ROGERS STORIES

- Mar. 1, 2021: Hornbaker fills a ‘glaring void’ in wrestling history with Rogers bio

- Nov. 10, 2020: Time to strut; biography on Buddy Rogers announced