Abe Jacobs took a decades-long ride on the strange torpedo called professional wrestling that carried him to all corners of the globe.

Jacobs, who will be honoured in June 2008 by being inducted into the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Hall of Fame at the Dan Gable International Wrestling Institute and Museum in Waterloo, Iowa, made a name for himself competing in numerous NWA World Heavyweight Championship bouts against the likes of greats Lou Thesz, Gene Kiniski, and Pat O’Connor.

“I had some great championship matches with (Kiniski),” Jacobs told SLAM! Wrestling, explaining that he felt they really gelled together in the ring. “I’ve just about worked with them all at one time or another.”

Jacobs also won tag team gold on several occasions.

“Don Curtis and I won the World Championship in Florida. Then I was with Haystacks Calhoun. We were in this area (Carolinas) and went across to Los Angeles and we won the International Championship,” he said, adding he and Pez Whatley also captured the Western States belts in Amarillo.

Born and raised on a ranch on New Zealand’s Chatham Islands, Jacobs remembered being a fan of professional wrestling growing up in the 1940s, listening to matches broadcast on radio Monday and Thursday nights. (Some years later he would wrestle the men he heard about on radio.) Jacobs could remember seeing pictures of the wrestlers in newspapers and he yearned to one day be as big as them.

“I was tall and skinny but I worked out on weights and put on some weight.”

The weight work would serve him well in his amateur wrestling career, in spite of the conventional wisdom at the time that urged athletes like wrestlers to shun weightlifting so to avoid becoming slow and “muscle bound.” After reading a magazine article at the time that claimed the fastest moving body in the Olympics belonged to an Egyptian lightweight power lifter performing the snatch, Jacobs became convinced that the common theories about weight training could not be more wrong.

His hard work on the ranch combined with his weight lifting gave him a distinct strength advantage, he said. Jacobs wrestled in the amateur ranks for 10 years. He won seven provincial titles, was a runner-up to the nationals and a winner of the national championships, and even tried out for the Olympics.

He decided to turn pro soon after his Olympic bid attempt. Jacobs received help from George Bollas (a.k.a. The Zebra Kid) who had been a Big Ten Wrestling Champion. He liked Jacobs’s amateur credentials and got around to talking to promoters to get Jacobs booked.

Jacobs debuted in 1958 at the age of 20, and after about a dozen matches in New Zealand, he moved on to Hawaii. He wrestled there for three months before moving on to New York and working for Vince McMahon Sr.

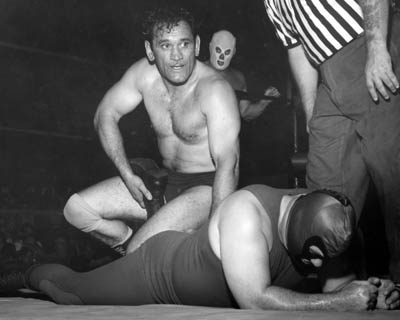

Abe Jacobs ties up one of the Infernos. Courtesy of the Wrestling Revue Archives

Jacobs would take numerous overseas trips as well, wrestling in Japan and all over Asia, as well as spending time in South Africa, Australia, South America, and Europe.

“I was single and that enabled me to get around to these countries. It was a little tough with the language problem. It was great to see these countries but I couldn’t speak to anybody about it,” he joked.

In Japan and South Africa, the promoters liked their wrestlers heavy, so Jacobs would often perform at around 270 pounds. More typically, however, the six-foot-two Jacobs wrestled between 240 and 250 pounds. In any case, however, he would be working an extremely heavy schedule that rarely let up.

“You were going. I would go five or six times a week, and some places more. I think one time when I was in Australia, I wrestled about every night, plus we did three television shows, one in Brisbane, Sydney, and Melbourne.”

It’s no surprise then that Jacobs estimates that he must have finished his career with over 8,000 matches.

Aside from the TV matches which had 10-minute time limits, rarely did Jacobs wrestle for under 30 minutes, and many matches went as long as an hour or more.

“I was always in good shape. I’m still in good shape. I work out all the time and I could go out and wrestle tomorrow,” he said.

Jacobs would also return to North America between trips, wrestling in Eastern Canada, Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, and even North Bay, Ont., in addition to Detroit, Chicago, the Carolinas, Florida, L.A. and San Francisco, and Amarillo, Texas.

Abe Jacobs. Courtesy of the Wrestling Revue Archives

Having amateur skills in addition to knowledge of submission wrestling served him well in Nova Scotia at one time, Jacobs recalled, remembering a persistent fan who kept deriding the wrestlers as fakes. At one point, this so-called “fan,” who had already been escorted out of the building once for getting on the house mic and lambasting the crew, entered the locker room to again dare the boys. When the promoter agreed to pay Jacobs to wrestle the guy in the ring, it did not take long before Jacobs had put the man in a painful submission hold.

Jacobs remembered the man quickly giving up, claiming he wanted to go fishing the next day. But Jacobs refused to release him until the man apologized to the crowd for what he had said. Which, of course, the man immediately did.

Jacobs wound down his career working mostly under card matches in the Mid-Atlantic area from the mid-1970s until the early ’80s.

“I wrestled steady and I liked it around this area. I should have left and gone someplace else but I wound it down around this area. I did go overseas and had a few matches after I (left) the Crocketts.”

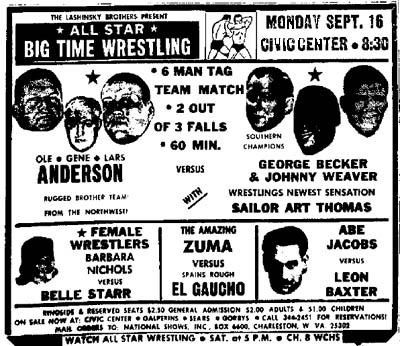

A 1968 card featuring Abe Jacobs.

CHANGING FACE OF WRESTLING

The wrestling business Jacobs left hardly resembles the one that exists today.

“At one time there were over 30 promotions in Canada and the U.S. The NWA was like a union among the promoters.”

That changed when Vince McMahon Jr. came along and essentially took over the entire business.

Jacobs was not sure the change has necessarily been a good one. “Wrestling once drew more fans than any other sport in the country. And now it probably draws less than any other sport,” he said.

Abe Jacobs puts up his dukes in a bout against Hiro Matsuda. Courtesy of the Wrestling Revue Archives

Jacobs noted that there is a lot less television exposure for fans now than there was back in the day.

“When television first started, wrestling was one of the easiest things to televise. … Then when I was wrestling, and I’m talking about the Carolinas, they would televise matches and send it all around the area. … And however long it took to go around the territory, they would then tape another show.”

Those shows would be broadcast on day- and night-time slots to capture as many viewers as possible. With so many promoters following this format, Jacobs believed wrestling reached more people back in the previous territory days.

The WWE’s dominance also has meant a lot fewer spots open for wrestlers to earn a living wrestling fulltime.

Jacobs noted that from the moment he turned pro, he did nothing else but wrestle for a little under 30 years. He wrestled in 25 different countries and went around the world four times.

“It was great. And now that’s all gone.”

Today’s wrestlers are also taking far more dangerous risks than was once the norm, with ladder and table matches commonplace, and Mick Foley going so far as to be tossed off the top of a steel cage. Jacobs did not so much criticize the hardcore approach as he did sympathize with the guys taking the punishment, warning that no one can get away with such a style and walk away without incurring serious injuries.

“It’s changed a lot and it’s not quite what I remember,” he said, admitting he has stopped watching wrestling, partly because he is no longer personally familiar with today’s stars.

Still, his love for the sport that made him famous has not abated: “I always wanted to treat wrestling great because it treated me great,” he said, later reflecting: “It was a long time but I look back and I liked every bit of it.”

RELATED LINKS

- Aug. 23, 2023: Abe Jacobs, pride of New Zealand, dead at 95

- Jan. 24, 2022: Mat Matters: An appreciation for the wonderful Abe Jacobs

- June 28, 2008: Piper, Saito, Jacobs enter Tragos/Thesz HOF

- Tragos/Thesz Hall of Fame story archive