Part 2 of 4

- Part 1: Seelie Samara a forgotten African-American great

- Part 2: Seelie Samara a star around the world

- Part 3: The final years and legacy of Seelie Samara

- Part 4: Big George: The origins of Seelie Samara

Professional wrestling history was made on March 13, 1938, as Seelie Samara, the Ethiopian wrestling champion and confidant of Emperor Haile Selassie met Steve “Crusher” Casey for the American Wrestling Association (AWA) World Heavyweight Championship. While this achievement is rightly heralded as the first instance of a African-American wrestler challenging for a major world title, it belies Samara’s other claim, that of being the world’s first Black World heavyweight champion — two decades before Bearcat Wright and over six decades before Ron Simmons.

However, Seelie Samara’s world title run ended without fanfare, and he found himself at odds with Boston promoter Charley Gordon. In a business that rewards risk takers, Samara — real name George Hardison — did just that. Leaving Gordon’s Massachusetts’ Wrestling Association (MWA), Hardison hitched his wagon with another promoter — Jack Pfefer — and set out first for New Jersey and then the world.

George Hardison had an impressively long career — spanning generations and influencing careers across North America and the world. In part two of the remarkable story of George Hardison, we’ll trace Samara’s path across the North American continent. While the name of the Samara character might change, the results were the same regardless of the location. But the story of George Hardison is more than just endless success; it’s also the story of racial inequality, of “separate but equal,” and how a handful of courageous Black wrestlers proved that not even divisive racial politics could keep a great wrestler down.

Jack Pfefer was a powerful-but-volatile wrestling promoter from New York. He would help guide Samara’s career for the next few years.

Pfefer Talent

By 1939, the wrestling landscape dramatically differed from just a few years earlier. The major wrestling war was over, with the origins of the territorial system beginning to lay its roots across North America. Hardison’s relationship with Pfefer opened the door to bookings across the United States — places he would pass through, places he would star, and places he would come to call home.

Much of Samara’s 1939 and early 1940 was spent in the rings of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. His post-Boston career began with a one-night-only tournament for promoter Bert Bertolini in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The tournament, a popular attraction for promoters in the period, featured seven grapplers competing in 20-minute time-limit matches until only one man remained standing. At stake was $500 and a title shot against reigning mat king, Jim Londos.

The contenders included many popular acts, like Chief Little Wolf, Babe Zaharias, the Golden Terror, George “Red” Ryan, Tommy O’Toole, and Nick Campofreda. Samara was bested in the early rounds, despite dominating against the underdog Prince Ali Gandhi. Taking his opponent too lightly, Samara was caught off guard by his foe, losing surprisingly. Despite the loss, the popularity of Samara was undeniable, with the Evening News on January 13, 1939 calling his match “one of the cleverest mat duels witnessed here in many months.”

Despite his loss, the local sportswriters (and fans) were enamored with the impressive Samara. “Only one other Negro, Reginald Siki by name, who is campaigning in France,” stated the article, “has been as successful as Samara.” Hardison had reached lofty heights in a short span of time.

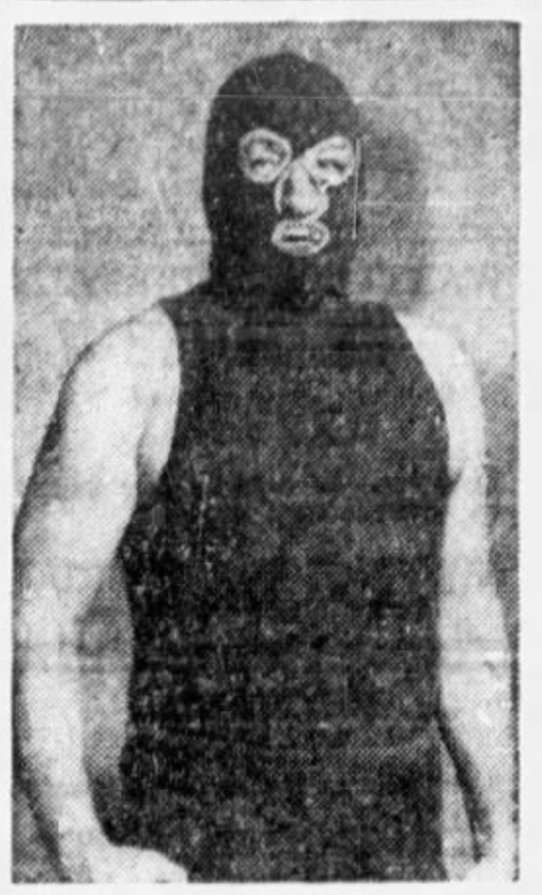

Seelie Samara wearing his head wrap.

Family Life

Joining the Pfefer crew meant a major change for the young Hardison family. By 1939, the family had expanded dramatically. Mary and George now had four mouths to feed, with Douglas (age eight), John (age seven), George Jr. (age six), and at least one daughter, Janice (age four).1 Shifting their base of operations was a big ask for the family, but providing the best for their kids was essential.

While it’s tough to gauge how the young Hardison family fared while dad was away wrestling, the family unit appears to have settled in the Summit, New Jersey, area. The couple’s original home, Greenfield, Massachusetts, had served them well, but a globetrotting wrestler needed a central base — and Hardison found that in Summit.

His wife, Mary, hoping to help provide for the family, took up a role as a laboratory technician for the Millmaster Berkeley Chemical Company in Berkeley Heights, NJ. It was a role she would hold until her retirement.2 The income from the technician role was a godsend for the family, as the rigors of travelling for wrestling meant that George would need to double down on bookings to make up for his lost salary as a truck driver.

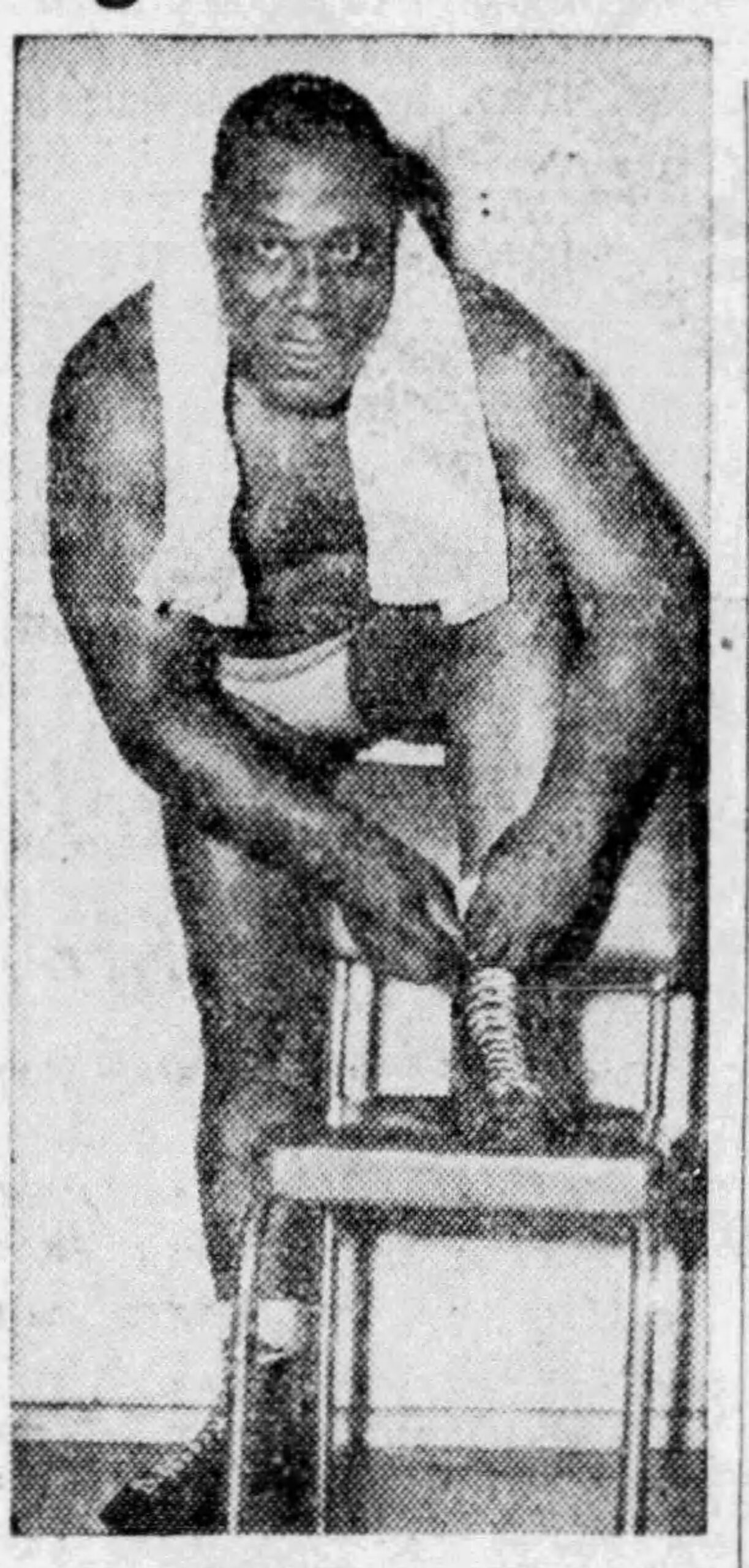

A headshot of Seelie Samara.

Road Warrior

And hit the road George Hardison did. From 1940 and ticking over into 1941, Hardison, as Samara, continued to travel and build an impressive reputation as a hulking fan favorite, facing names like Hans Kampfer, Ole Olson, Ken Fenelon, and more. He became a popular attraction in Wyoming for promoter Tom McCarthy, in Colorado for Hank Loure, in Illinois for upstart Fred Kohler, and elsewhere.

He was a major star in Wisconsin from the very start, easily defeating local hero Jack Estes at the Eagle Auditorium in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, on January 9, 1940. Billed as an “Algerian powerhouse” by the Sheboygan Press, Samara battered Estes with an unrelenting barrage of offensive maneuvers. Estes, simply aiming to hold on against his much stronger foe, eventually succumbed to serious, devastating body slams, followed by a body press for the pin. The Sheboygan Press highlighted Samara’s impressive credentials and skills, noting that he refused to defeat Estes with a hold or lock, instead desiring to overpower and pin his opponent to establish his name locally.

Samara was especially popular in Michigan, where he was described as a “one-man show” by the Herald Press. Samara headlines numerous cards in Benton Harbor, for promoters Joe Caplan and Augie Piehl. The pair rejuvenated wrestling in the area, with Samara facing the popular (if grotesque) Swedish Angel, Polish champion Karol Krauser (the future Karol Kalmikoff), and Gorilla Grubmyer.

Roy Dunn was another earlier foil, squaring off against Samara seven times alone in 1940. Dunn was a wrestling prodigy, having been a dual-sport star at Northwestern University. Dunn competed as a tackle on the football team and was a founding member of the school’s wrestling program. After competing for the United States in the 1936 Olympics, Dunn turned pro, quickly rising up the ranks. By 1941, he held a distant claim to the world title in Kansas — a claim that was never merged with the orthodox NWA title lineage.

Changing Management

Just when Samara ended the Pfefer relationship is unknown, but by early 1944, Samara was getting bookings under Ray Fabiani, Philadelphia wrestling impresario. Nicknamed “the fiddler” — due in equal parts to his previous life as a violinist in the Chicago Civic Opera Company and his less-than-scrupulous behind-the-scenes machinations — Fabiani was a well-connected force in wrestling across the U.S.

The fallout with Pfefer was likely early and equally likely about money — a constant gripe from some of Pfefer’s less happy clients. There are a handful of non-appearances of Samara at bookings, the most notable example being a suspension in Michigan.

Michigan’s State Athletic Commission suspended Hardison in late 1941 for a failure to appear as advertised. This suspension impacted Samara’s career, as Benton Harbor was one of his most popular destinations. Losing those bookings would be costly for a family man. (Benton Harbor was also home to Houston Harris, the future Bobo Brazil.)

Fortunately, Hardison kept getting dates in the surrounding states and out west and eventually returned to his old stomping ground a year later — likely under new management. Hardison had diverse options, as he featured prominently on several Al Haft cards — particularly cards featuring his mentor, John Pesek. Pesek’s close association with the barnstorming Samara is evident as early as the summer of 1940 when Pesek was already on the “stand-by” list to fill a scheduling gap against Samara for the Salt Lake Wrestling Club.

It’s likely Pesek was serving a behind-the-scenes role and was nearby, but the old teacher and the young student did square off at least a handful of times. These matches include an early bout on April 20, 1939, in Columbus, Ohio, for Pesek’s Midwest Wrestling Association (MWA) World Heavyweight Championship, with Pesek the victor.

Hardison also competed under the name Ras Samara, with this designation tending to be favored around the central United States. The first appearance of the name was on November 5, 1940, in Omaha’s Evening World-Herald — “One of Haille Selassie’s Boys to Meet Singh Singh Monday”. This time, however, the story went that Samara was a wrestler-slave under the emperor before Mussolini overthrew his rule and set Samara free.

Ras Samara was a constant talent on cards of Omaha, Kansas City, St. Louis, St. Joseph, and more, facing off against a huge array of opponents, including Al Caddell, Leo Mortenson, Babe Zaharias, Tug Carlson, Orville Brown, and more.

Another prominent rival was Jack Conley, a Rocky Mountain native and a bruising 245-pound heavyweight who knew a wide assortment of holds. Conley and Samara squared off across the Midwest, competing in at least 20 (but likely far more) matches from 1939 to 1951.

Under the Fabiani umbrella, Samara made his west coast debut in March 1944 for promoters Harry Rubin and Charley Jelinek at the Municipal Auditorium in Long Beach, California. On March 23, 1944, the Long Beach Sun, creating anticipation for the import of fresh faces, called Samara, billed as Ethiopian champion, as “one of the wrestling marvels of recent years.”

Battling primarily against Myron Cox, Samara staged many exciting bouts across Southern California. Samara gained the edge via a string of exciting maneuvers — including airplane spins, octopus holds, and some of his famed leg locks.

The popularity of Samara extended far beyond the Southern California area, however. His star also shone in Northern and Central California and Arizona. Samara is often erroneously listed as having defeated Geroge Koverly for the Pacific Coast Heavyweight Championship in 1944. This, however, was impossible, as Samara was facing Jim Londos for the World Heavyweight Championship in Los Angeles on the evening in question, November 29, 1944. 3

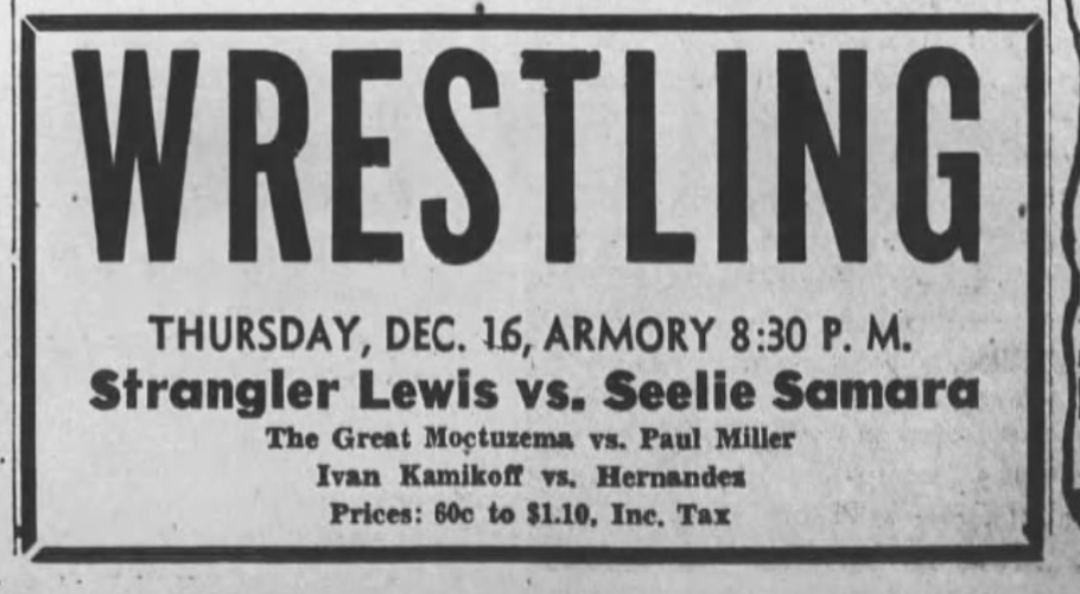

Opponents in this era also reveal the popularity Samara enjoyed from both crowds and promoters, with major names like Ted Christie, Fritz Schnabel, Jim Casey, Abe “King Kong” Kashey, and even the legendary former champ, Ed “Strangler” Lewis, lining up to take on the “Negro Hercules.”

Defining the Samara Character

It was in the early years of Hardison’s travels that much of the Samara character’s distinctive style was born. A fan favorite, Samara had power and technical prowess in equal measures. His muscularity was unique for the era; his bulging physique was a striking contrast to the bulkier frames of many heavyweights of the period.

The Samara character also included costume elements — the most noteworthy of which was a Muslim head wrap Hardison used when being advertised from Algeria (his most common birthplace) or Afghanistan. Still, given the huge number of strange hometowns, it is difficult to keep track of exactly what character elements are geographically based and which are just random items based on the fanciful imaginations of “Africa” from countless midwestern promoters.

But a sense of fair play, honor, and respect defined the Seelie (and variants Ras and Haille) Samara characters to audiences. Combined with his impressive physique, these virtues earned him lasting nicknames, including “Negro Hercules,” “Black Adonis,” the “(insert location here) Wildman,” and famously, the “Black Panther.”

The latter nickname was something of a misappropriation. Al Haft, the Columbus, Ohio, promoter, had Samara wrestle under the Black Panther name for several appearances around late 1939 and early 1940, defeating Turp Grimes and Jack Zarnes while losing to the rugged Bobby Bruns.

The irony of the “Black Panther” nickname and Seelie Samara is that it was not Samara’s true nickname; rather, it was used as a stop-gap while the actual “Black Panther,” Jim Mitchell, was away from the territory. Mitchell was a veteran wrestler by 1940 and was a top attraction in many areas, including the Midwest, Pacific coast, and overseas in Europe.

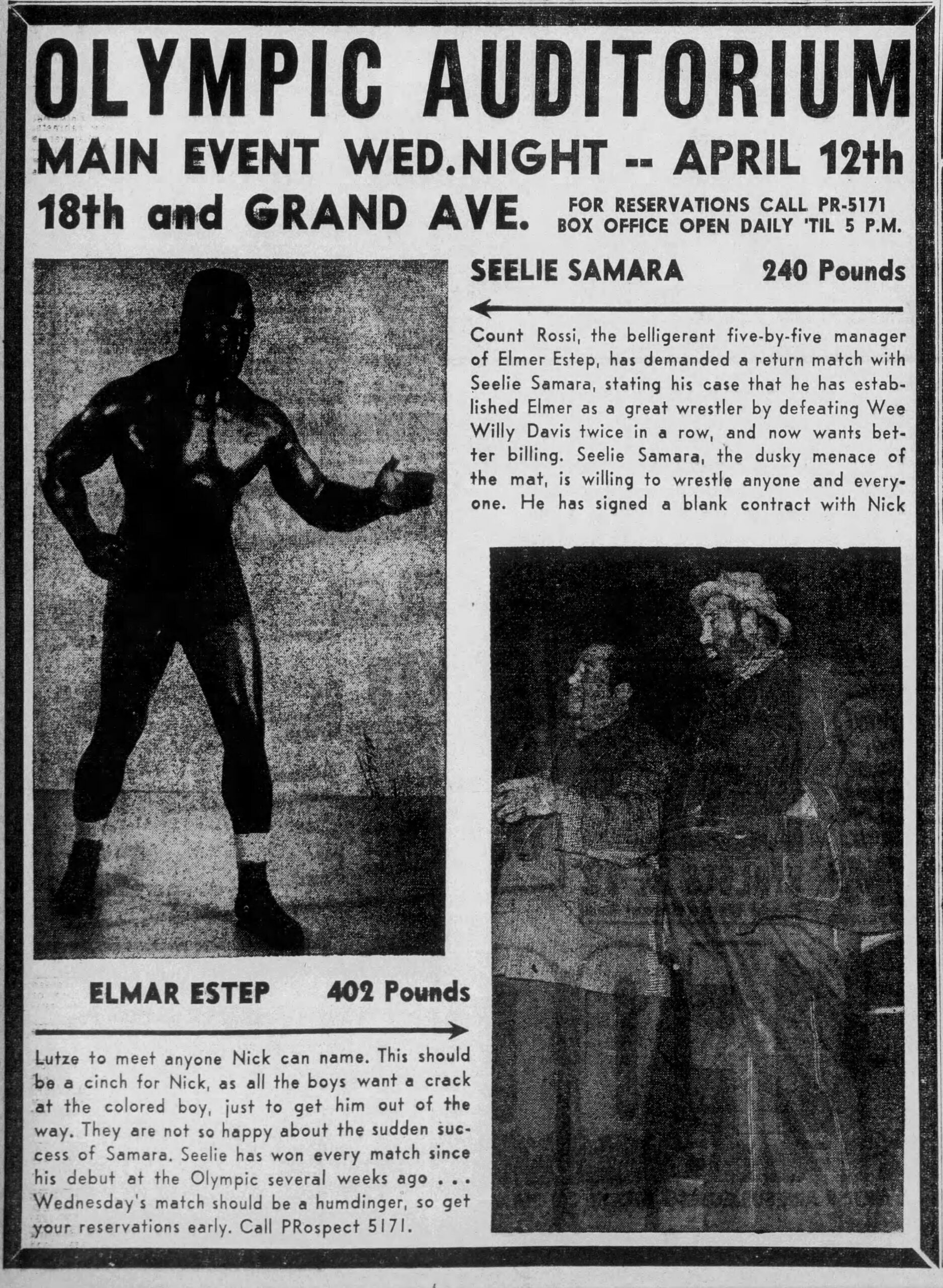

Promotional ballyhoo from Los Angeles in 1944.

Wrestling with Injustice

Another prominent series of bookings for Hardison centered around the segregated “colored bouts.” Fortunately, many of the African American talent the hulking Samara was booked with in his early career were super performers. The myriad combinations often grabbed the headlines — and garnered rapturous applause. These grapplers included wrestlers like Jack “Gentleman” Claybourne and Leroy Howard “King Kong” Clayton.

Clayton was a boxer-turned-wrestler, having held some regional middleweight belts during his pugilistic career. Samara and Clayton squared off frequently in the early-to-mid ’40s, including featuring on some early Sam Muchnick cards in St. Louis. The pair clashed in a co-main event feature — a one-fall match sharing the honors with a two-out-of-three falls affair between Bobby Bruns and the Swedish Angel — at the St. Louis Arena on Friday, March 27, 1942.

Describing the action in its April 1, 1942 edition, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch stated that Samara, “whose powerful legs demonstrated more realistic scissors and foot locks than that ordinarily seen in wrestling shows these days, won from King Kong Clayton in 36:06.”

George Hardison again found championship glory in the segregated ranks, winning the “Negro World Heavyweight Championship” from longtime champ “Gentleman” Jack Claybourne on August 5, 1941.

Hardison, now using the much more on-the-nose ring name, “Haille Samara,” was an important talent for Heywood Allen, the promoter of the Allen Athletic Club in Kentucky. Despite being confined to segregated bouts, Samara defended his world title against names like “Black Panther,” Claybourne, and “King Kong” Clayton in main events and semi-mains.

He would drop the title back to Claybourne in the summer of 1942 before regaining it when Claybourne left to serve overseas in December 1943. 20 He would hold his claim for the Negro World Heavyweight Championship into the 1950s — though there’s no conclusive date for when (or if), he lost that crown.

The fans didn’t know he was an American from Georgia. To them, he was the hulking Hercules of any of several geographical attestations: Abbysinia, Algeria, Brazil, Cuba, Ethiopia, Senegal, and Afghanistan. To them, he was a great champion of the world and a powerful, technical, and virtuous battler worthy of their cheers. And cheer they did across the country.

But the realities of pre-Civil Rights America meant that, more often than not, George Hardison found himself forced into segregated matches just to get bookings. Unless he had his influential friends on the cards, it seemed like George Hardison’s career had peaked.

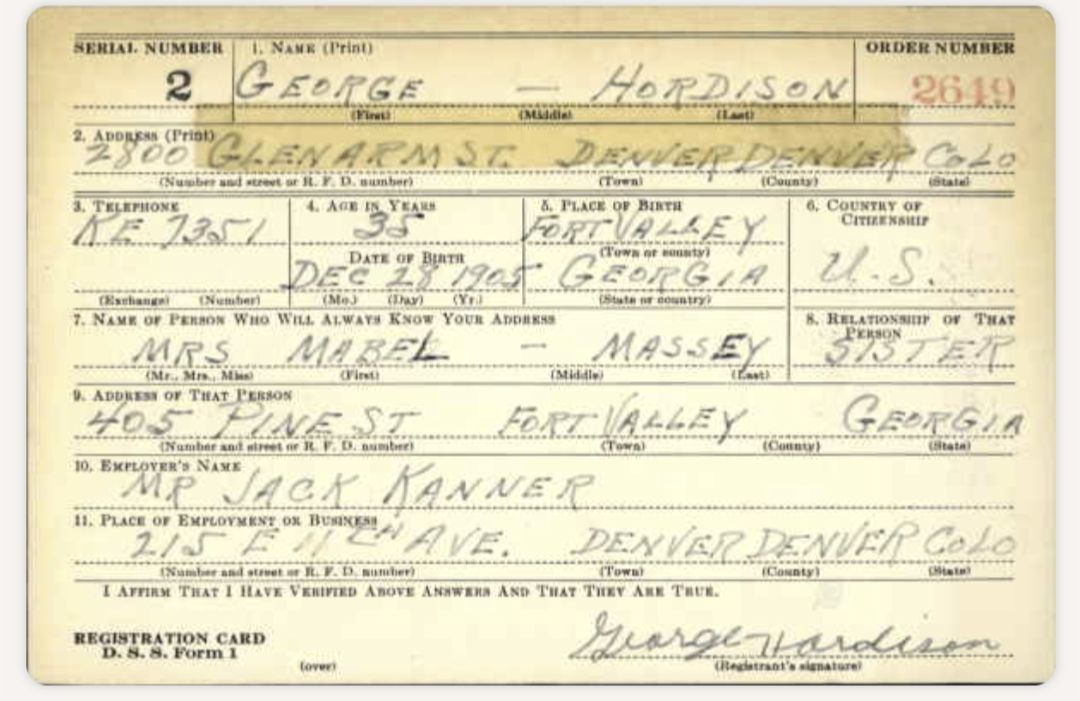

George Hardison’s draft card. Note the spelling of the name “Hordison.”

Military Service?

As World War II was underway, many wrestling stars saw their livelihoods put on hold as their country called.

Hardison’s 1940 selective service registration card lists Hardison’s current residence as Denver, Colorado, and his employer as Jack Kanner, the local promoter. The document also highlights the close bond Hardison maintained with his family, listing his sister, Mabel, as his point of contact in Georgia. 4

While military service was assumed, finding any details about Hardison’s military career is near impossible. This difficulty stems from the inconsistency with which Hardison completed government forms. His draft registration, for example, uses the name “Hordison,” while other documents use the correct “Hardison.”

Hardison’s career also has relatively few gaps during the Second World War. While this implies Hardison didn’t serve during the war, this is misleading. Numerous wrestlers-turned-soldiers took bookings while in the service, getting permission to perform in the evenings (often under a pseudonym) or while on leave.

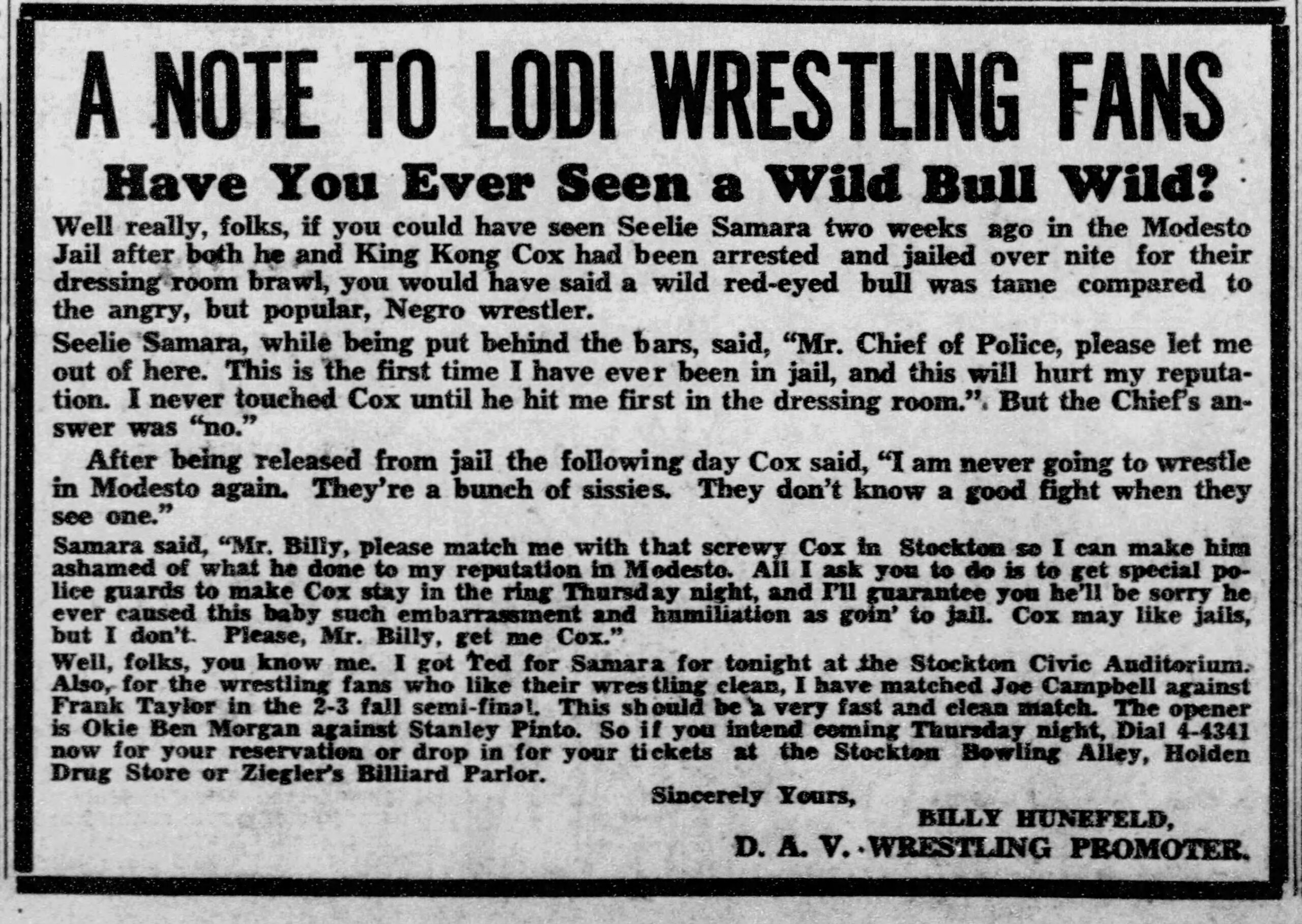

A wordy ad from Lodi, California, from September 1944.

Australia

While a military career is unknown (if unlikely), what is known is that by July 1946, Hardison was in Melbourne, Australia, on his first world tour. Ted Thye arranged the tour. Thye, a former grappler-turned-promoter, had formerly been focused on American grappling but found a lucrative trade in promoting tours of New Zealand, Australia, and other Pacific nations. The Australian style was an entirely new wrestling style for Samara — but one he would quickly learn to thrive in. Unlike the U.S. style, Australian matches relied upon a rounds system with eight rounds, the typically scheduled limit. Other names on tour included Lou Newman, Jan Wright, Bob Cutler, Babe Small, Hans Schanebbel, and Jess Christie, brother of Vic Christie.

Samara was an instant hit on the tour, defeating Fred Atkins, Australian champion, two falls to one at the Sydney Stadium, with what the local fans dubbed the “V2 flying toehold” — likely the “flying horse.” The Sydney Morning Herald made note of the unique hold in its July 16, 1946 issue: “New Move by Negro Wins Wrestle” His trend-setting streak extended the next week, as Hardison became the first Black wrestler to participate in a Victoria match, as detailed in Melbourne’s paper, The Age.

Success continued to follow the tour — and Samara — with over 11,000 fans jamming into the Sydney Stadium for an early August bout with Jaget Singh — another record — while Samara continued to pick up wins against the likes of John Katan, Frank Cutler, Lou Newman and others across the country.

Here’s footage of that John Katan matchup, courtesy of British Pathe Films:

Perhaps Samara’s most important event in Australia came late in the tour when Hardison was set to square up with an old foe for the world’s title. The match, which took place on November 18, 1946, at Sydney Stadium, brought George Hardison back to the top of the wrestling world. Once again, the ex-boxer was up against a strong, skilled European Champion — with Londos providing the stiff competition.

At stake was more than just any world title. Londos held a claim to the original World Heavyweight Championship — the belt held by the legendary George Hackenschmidt — and a claim dating back an impressive six years, back to a victory over NFL legend Bronko Nagurski in late 1938.

Also up for grabs was Londos’ diamond-studded championship belt. Press reports claimed the belt was valued at $10,000 — a huge prize worth the gamble for Samara. Again, Samara came up short, but the impression he made lasted a lifetime:

“Londos triumphed over Samara because of his almost incredible swiftness and amazing versatility, against which Samara’s power, determination, and ruggedness were ineffective,” said a report in the Sydney Morning Herald. “Londos obtained a fall in the fifth round. Samara, shattered by a back slam and a series of Boston crabs, moved from his corner at the start of the sixth round, obviously in pain. Londos pushed him to the mat effortlessly, and the referee ended the bout immediately.”

The Australia trip seems to have rejuvenated Hardison’s career. He departed Australia via plane and had layovers in Auckland, New Zealand, and Honolulu, Hawaii, before finally reaching San Francisco. Upon his return to the American mainland in 1947, the giant was immediately placed into title matches, with the Rocky Mountain Heavyweight Championship his first target.

But international travel would become a fixture of Hardison’s wrestling, with further tours dotting his career. So popular was Samara Down Under that he returned just a year and a half later.

Samara’s impact on Antipodean grappling is best stated by a 1950 article in the Sydney Morning Herald, discussing some of the problems Australian wrestling faced — not least with the rising costs of bringing in and maintaining star American grapplers due to a declining British pound.

Despite the difficulties, these grapplers were an essential part of the scene, with the “special correspondent” noting key names that would always be associated with the sport in the country. These names included “Dirty” Dick Raines, Sammy Stein, Ray Steele, John Pesek — and Seelie Samara.

Again Samara was a featured attraction on the 1949 tour, starting with another lengthy undefeated streak. Arjan Das, Pat Fraley, Chief Little Wolf, and Marvin Jones were some of the names facing the ferocious Samara. His last date in the Southern Hemisphere was a point win against Al Costello on November 21, 1948 — ending with a symbolic victory over a “Kangaroo.”

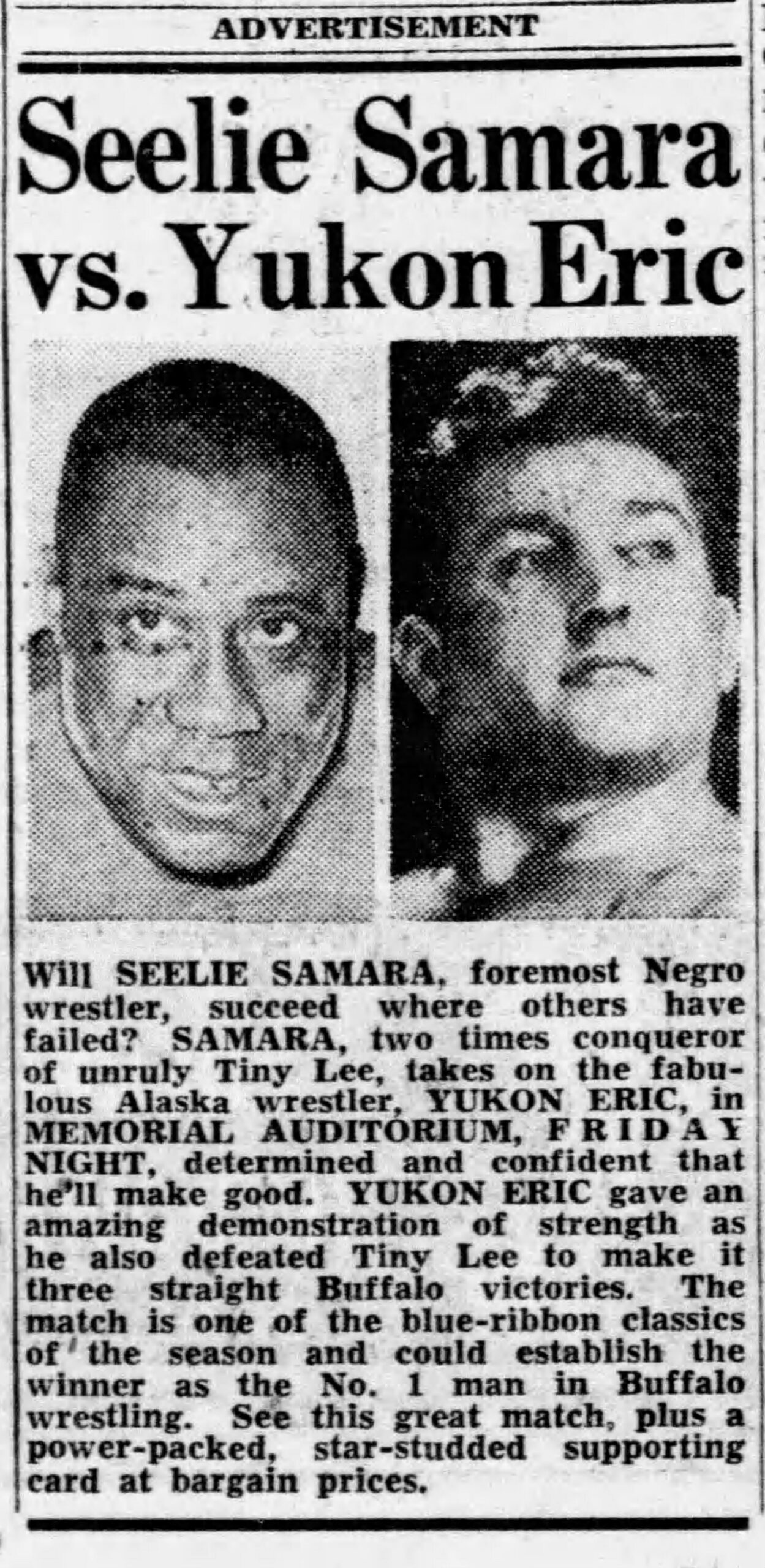

Wrestling in Buffalo in December 1949.

Canada

Perhaps Seelie Samara’s biggest impact was made in Canada. The Post-Standard in Syracuse, New York, stated as much, writing on March 6, 1950:

Samara has been more than a mild sensation wherever he has wrestled. Australian promoters were reluctant to let him return to the states after he had riddled the field in the land Down Under.

San Francisco promoter Joe Malcewicz still rues the day that he permitted Gorgeous George to enter the same ring with Samara; and up in Buffalo, Samara has become such a tremendous favorite that there is a movement underway to bring about a match with world’s champion Frank Sexton.

Right now, Yukon means more to the Syracuse promoter as a box office attraction. But one good look at Samara’s accomplishments in other wrestling centers seems to satisfy promoter Bennett Magin that he could easily replace the Alaskan lumberjack. Hence the words, “Don’t sell Seelie Samara short.”

Yukon Eric, born Eric Holmback, was a massive star in Southern Ontario and Quebec. A frequent partner of Whipper Billy Watson, Yukon Eric is best known for a 1952 bout with Walter Kowalski in which an errand knee drop caused Eric to lose his ear and Kowalski to replace his “Tarzan” moniker with something more fitting: “Killer.”

Holmback and Hardison squared off numerous times over the years, with Holmback holding the edge — including a semi-main victory at the Montreal Forum on December 6, 1950. It’s worth noting that before Holmback adopted the “Yukon Eric” name, he had never beaten Samara, his luck seemingly tied to the popular gimmick.

Seelie Samara enjoyed tremendous popularity in Ontario — including challenging the ever-popular Whipper Watson for his British Empire Championship in Brantford, Ontario, on February 1, 1951. In a finish reminiscent of the Londos title match in Australia, Samara withstood tremendous punishment from Watson, narrowly avoiding a count out and proving his meddling. Samara eventually fell to Watson’s feared “whip” but again showed his value as a wrestler.

Calgary and the Canadian west were other important areas for Hardison. During 1952 and 1953, Samara teamed with another underappreciated wrestler: George Gordienko. The two made a strong pairing, defeating Al Mills and George Tolos on November 11, 1952, in Edmonton. Their clean-cut approach and silky-smooth styles made the team’s synchronicity as good as a singles match between the two, which occurred first, a week before. The match buildup, under the headline “Classy Matwork On Tap Tonight,” noted that the “mat smoothies meet in the 45-minute semi-windup and some classy wrestler will be the highlight.”

The years 1952 and 1953 saw a sharp decline in Seelie Samara’s bouts. This, in part, can be traced to a severe bout with influenza that struck Hardison down in early 1952 in Great Falls, Montana, warranting a sudden change in the card. He returned a few weeks later before vanishing again until September 1952.

The Edmonton Journal of September 5, 1952, announced the return of several popular grapplers, including Samara, who it claims was “just back from Singapore and Egypt.” Those tours likely involved matches against Dara Singh and “King Kong ” Emile Czaja.

After a few bouts with Chick Garibaldi in South Dakota in early 1953, Hardison and Samara vanished from the record again. This time, he appears to have been on tour in India. A brief note in the January 13, 1954 edition of Sport’s Editor Johnny Hopkins’ “Speaking of Sports” column in the Red Deer Advocate noted that “Seelie Samara…has just returned from India.”

Samara’s return to North American wrestling appeared in a January 6, 1954 article in the Edmonton Journal, stating that promoter Al Oeming planned to bring the popular Samara back to the Sales Pavilion.

The previously mentioned Red Deer article also sheds some light on the bizarre shift to billing the supposedly African wrestler from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. According to the column, Samara kept a palatial estate in the city and owned numerous businesses. It was bluster, of course, but at least they kept the story straight.

Throughout early 1954, Samara regained his position in the territory, main eventing cards against Frank Marconi, Tommy O’Toole, Tony Angelo, and more. He also made a successful team with Bob Mike, an ex-football-star-turned-wrestler, and Jean Baillargeon, winning the Canadian Tag Team titles with both partners.

“Mister E” was really Johnny Carlin. It was a gimmick he’d previously used in Utah and would later use again in Kentucky before retiring.

One of the more unique feuds for Samara was with a masked man known only as “Mr. E.” The mysterious grappler first appeared in 1954 in Edmonton. The mystery man put the rulebook aside as he punished popular wrestlers in the area — despite promoter George Jacob’s best efforts. The mysterious one was scheduled to meet Seelie Samara (billed from Rio de Janeiro), headlining a May 18, 1954 card at the Sales Pavilion in Edmonton. Unfortunately, Samara appears to have missed this date and another next week without explanation. He would never appear in the area again. 5

Final In-Ring Years

The middle and late 1950s saw Hardison’s travel decrease further, as he seemed to have settled into a schedule of working in Buffalo and the surrounding areas for bookers Pedro Martinez and Ed Don George. He also steadily worked the southern Ontario loop and remained as popular as ever.

Relegated to mainly working tag matches, Samara still held up his end of the bargain while teaming with Lord Athol Layton, Pat Flanagan, Tommy O’Toole, and Nick Roberts. Samara still had some singles matches, but more often than not, the aging star was on the losing end of the contest.

Samara’s final date in Canada appears to be April 18, 1956, in London, Ontario. Teaming with Gil Mains, Samara lost to the team of Sky Hi Lee and Fred Atkins. His final date in the western New York territory was a loss to Bob Leipler in Dunkirk, New York, on September 29, 1956.

Next time: We’ll take a look at the lasting legacy of Seelie Samara. Despite being absent from popular culture for over 75 years, the name “Samara” continues to bubble up from time to time — especially in Australia — proving that nothing could stop George Hardison, be it financial hardship, long miles, racism, or even death.

RELATED LINKS

- Part 1: Seelie Samara a forgotten African-American great

- Part 2: Seelie Samara a star around the world

- Part 3: The final years and legacy of Seelie Samara

- Part 4: Big George: The origins of Seelie Samara

FOOTNOTES

1 — “Hardison Family Tree” Ancestry.com. Provo, UT

2 — “Mary Louise Andrews Obituary” Courier-News, Bridgewater, NJ. November 17, 1987

3 — Williams, John Hubert “Seelie Samara Biography.” Pro Wrestling Historical Society. 2019

4 — “George Hordison” World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947. National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for Colorado, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 113

5 — This is another instance of Hardison not appearing, as highlighted earlier. All told, he appears to have missed around 4-5 dates over the course of his nearly 30-year career. For those wondering, “Mister E” (also styled “Mr. E”) was Johnny Carlin, an experienced grappler who had previously held both the world light and middleweight championships. Interestingly, Mr. E’s biggest opponent in the area — and the man who took his mask — was Samara’s most frequent foe: Jim “The Goon” Henry.