Time wasn’t on Reginald Siki’s side and he hurried through the world as if he somehow knew it. He lived a life of extraordinary highs and lows and packed enough travel and excitement into his four and a half decades to fill multiple lifetimes. He was a star athlete on three continents in a career that lasted over 20 years. He wrestled in front of crowds that ran into the tens of thousands in America and Europe. He was married at least three times, sometimes to more than one woman at a time. He spent two years as a German prisoner of war during World War II, an experience that left him penniless and almost killed him. After his release, in his mid-forties, he managed to pull off an unlikely second act in a world that’s bullish on them, all while dealing with grinding racism and segregation in his home country.

Siki was one of the best known Black athletes in America in the era between boxers Jack Johnson in the 1910s and Joe Louis in the 1930s, but is almost unknown to wrestling fans and sports historians. He goes unmentioned in Fall Guys, Marcus Griffin’s 1937 tell-all on the wrestling business, and is noted just in passing in 1936’s From Milo to Londos, Nat Fleischer’s considerably more guarded history of wrestling. When Siki is remembered at all, it’s usually as the namesake for the much better-known wrestler Sweet Daddy Siki, who began his career in the 1950s.

The life histories of wrestlers from Siki’s era are invariably blurred by the intentional misdirections and falsehoods that perpetuate the strange world of professional wrestling. Sorting out fact from fiction is challenging with even the best researched subjects but with Siki’s life, the stories run deeper than most. Siki was born Reginald Berry in Kansas City, Missouri on December 28, 1899 to Richard and Ella Berry. Siki was one of four children though nothing else about his childhood is known. In fact, much about his life is currently unknown. He left behind no personal papers and died long before wrestlers spoke openly about their careers. What is known of him has been pieced together through newspaper articles, government documents, and scant information collected from family members. It’s hoped that by pulling together what is known, more attention will be called to him and some gaps in what we know about his life will be filled.

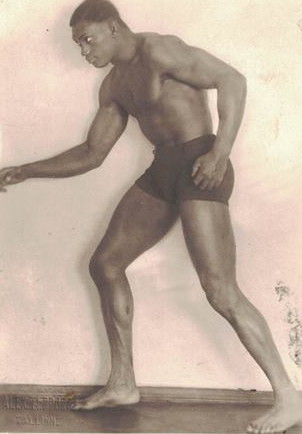

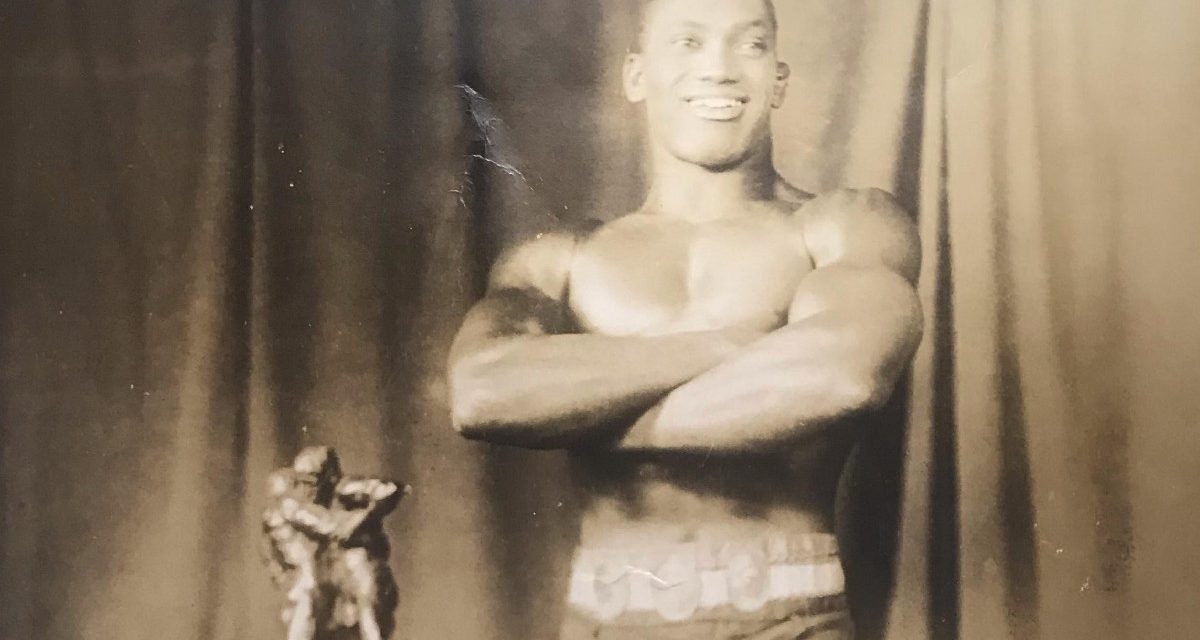

Siki began wrestling professionally in 1923. Over six feet tall and muscular with an infectious smile, he was most likely recruited into wrestling by the brothers Wladek and Stanislaus Zbyszko. 1 The ring name of Siki was undoubtedly a reference to the Senegalese-born boxer Battling Siki, who became a world-wide phenomenon in 1922 when he stunned boxing fans by defeating light heavyweight champion Georges Carpentier in Paris, France. One story has it that American soldiers who had seen Battling Siki fight in Europe gave the name to Berry after seeing him box, though it is more likely that Berry either adopted the name himself, or was given it by a promoter hoping to capitalize on Battling Siki’s sudden fame. 2

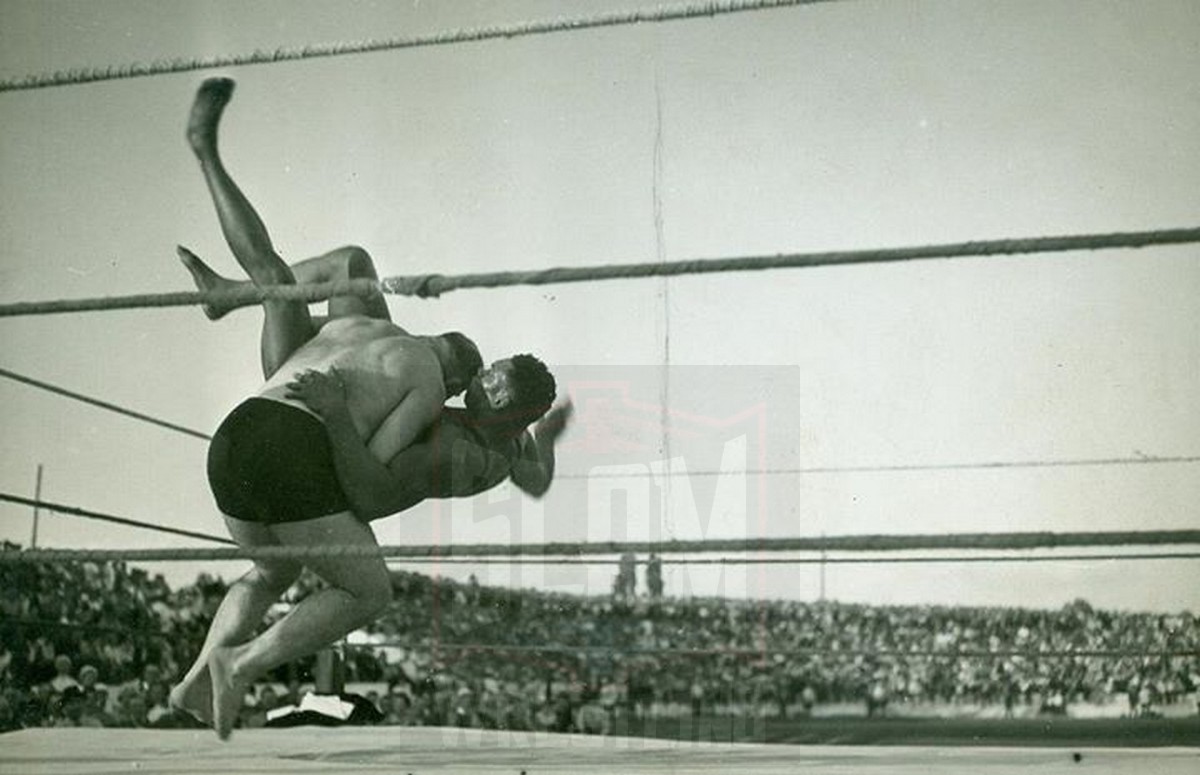

Dan Koloff and Reginald Siki wrestling in Bulgaria

Another invented yet enduring part of Siki’s persona was his birthplace. Instead of being listed from Kansas City, his birthplace was given to sportswriters as Abyssinia, the predecessor to modern-day Ethiopia. Reporters were told that Siki’s birth name was Dejatch Tedelba and advertisements billed him as the “Wild Man From Africa.” Some of the most outrageous stories, as Ring magazine recounted in 1931, presented him as “breaking into cooked food life as a wild, wild tribesman, bedecked in three beads, war paint, a scowl, and a stone hammer, who had been taken in tow by some French explorer-artist.” In the Canadian press he was referred to as “the gorilla man,” and said to be able to hunt and kill wild animals with his bare hands.

These stories were central to the press Siki received in the beginning of his career. They were likely invented by his early managers and elaborated on by the sportswriters themselves. They played on the unquestionably racist beliefs and fantasies of many fans, but promoting Siki as a non-American likely served at least two other purposes, as well; it placed him among the growing number of foreign-born wrestlers popular across America in the 1920s and, as his grandson Mark Brailsford says, it allowed American fans to take him as a full-blooded African, not as the American-born grandson of slaves. 3

It’s likely that other Black wrestlers were performing regionally at the time, but none had successfully toured the country prior to Siki’s debut in 1923. Viro Small is the earliest known Black professional wrestler in America. He began his career in the 1870s in Vermont, wrestling as “Black Sam,” and performed around the northeast before gaining more prominence in New York and eventually performing at the first two locations of Madison Square Garden. A wrestler named Ila Vincent performed in America in the early 1910s but struggled to find opponents, finding more success in Russia and several European cities.

Siki, however, was an instant success. In his earliest known matches he was paired against top talent like Frank Judson and Taro Myaki, a sign of his powerful connections within the wrestling business. There was immediate talk among sportswriters that he could be a possible challenger for the world heavyweight championship, but a match was never made. Both Joe Stecher and Ed Lewis, the heavyweight champions at the time, were said to refuse to defend their titles against him because he was Black, drawing the same race-based line instituted by boxers John L. Sullivan and Jim Jeffries, who publicly stated that only white athletes were fit to hold championships. 4

Lewis once claimed he was willing to wrestle Siki, but only in exchange for the entire cut of the evening’s purse. “I don’t take this stand because he is colored,” Lewis told reporters, “but due to the fact that the challenger is a giant in size and weight, with what I understand, tremendous strength. I don’t propose to take a chance of losing the title without being well paid for it.”

In reality, though, Lewis would have had little to fear had the match been made. By the 1920s the outcome of almost every professional wrestling match was determined in advance. Siki would certainly have gone into a match with Lewis or Stecher fully understanding that he was to lose. Why he wasn’t granted a championship match, then, becomes more complicated. Stecher and Lewis may very well have refused a match with Siki based on nothing other than his race. It’s possible, as well, that they were willing to wrestle him but that the managers and promoters who controlled wrestling refused to make the match either because of concern that fans wouldn’t want to see it, or for fear of pushback from local authorities. 5

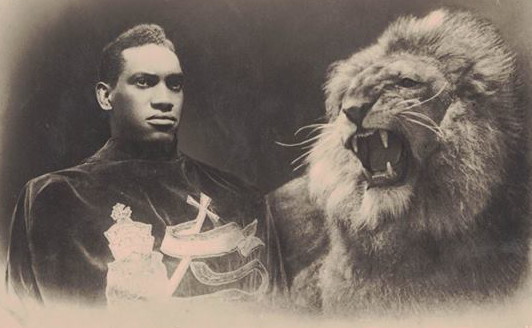

Siki moved to California in the fall of 1925. He worked predominately for Los Angeles promoter Lou Daro at the city’s newly constructed Olympic Auditorium, but was active up and down the state into 1927. He wrestled in main event matches in San Francisco with Dick Shikat and in Los Angeles against Jim Londos and Jim Browning, all future heavyweight champions. Siki was a thrilling performer, trusted by promoters and popular with fans. He also drew the attention of filmmakers who cast him in multiple movies, most famously 1927’s Tarzan and the Golden Lion (he was said to have lost out on a part in Cecil B. DeMille’s biblical epic The King of Kings because DeMille considered him to be too large).

Siki and the lion.

He moved to New York in late 1927 to work for promoter Jack Curley and in less than three months was working in main event matches with one of Curley’s favored wrestlers, Hans Steinke. Though popular, Siki departed New York and traveled to Europe in the spring of 1928 after less than a year in the city. Whether Curley and Siki had a disagreement or if Siki simply was ready to leave is unknown. 6 The timing couldn’t have been worse. Between 1928 and 1930, with the success of new champions like Gus Sonnenberg and Jim Londos, wrestling became unusually popular in America. Given Siki’s established relationships with promoters and his reputation among other wrestlers, he almost certainly would have been a featured performer. Instead he was abroad, where he was successful but out of the American spotlight.

From April of 1928 through May of 1930, Siki traveled throughout eastern Europe, appearing in tournaments in Poland, Russia, and Latvia. In many of these tournaments, besides being the only Black performer, he was also the only American. It’s not hard to imagine that it was a lonely life, though Siki adapted by learning to speak multiple languages. He also studied philosophy and photography, and once considered retiring from wrestling to open a commercial photography business. In Estonia, he met and married Ellen Syndenham, a 23-year-old white Russian-born beauty living in Tallinn. The pair traveled back to America in the spring of 1930 and moved to Ohio, where Siki went to work for promoter Al Haft and then to Boston, to work for Massachusetts promoter Paul Bowser. The best indications of Siki’s popularity during these years, and of Bowser’s support for his career, are the three matches he wrestled for wrestling’s heavyweight championship, once against Henri DeGlane and twice facing Ed Don George.

Photo by Alexander Jurich; Courtesy: Estonian Sports and Olympic Museum

In the fall of 1933, what is known about Siki’s life begins to get cloudy. In October, while living in Boston, he and Ellen welcomed their first child, a daughter named Regina. In late November, looking to escape the financial effects of the Great Depression and for a freedom from racial discrimination not available to them in America, the family returned to Estonia. Siki stayed busy with wrestling, booking matches in England, Bulgaria, South Africa, Hungary, France, and Greece. As in America, Siki was a trusted performer among European promoters. In his first match back on the continent, he performed in the largest football park in Athens. In Cairo, Egypt, he was matched against world champion Jim Londos. His 1935 matches in Sofia against the Bulgarian promoter and performer Dan Koloff drew the largest crowds for a sporting event the country had ever recorded.

Siki and Ellen separated sometime in 1936 but remained legally married. 7 Siki left Estonia and became a regular performer in wrestling tournaments in Germany beginning in October of 1937. “I keep busy year in and year out,” he wrote to the New York-based wrestling promoter Jack Pfefer in January of 1938. In that same letter, he asked Pfefer about possible offers to return to the United States, but it is unknown if any were made. Siki’s last appearance in a German tournament was in August of 1939. The next month, Germany invaded Poland and war was officially declared between Germany, France, and England. It was the beginning of what was later described by The Dayton Herald as “a checkered existence for Siki involving the Gestapo and ‘incidents’ interwoven with wrestling bouts and bombings.”

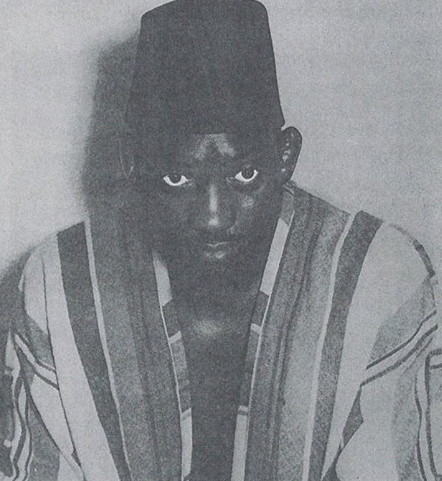

While living in Prague, Siki converted to Islam from Judaism and took the name Kemal Abd-Ur Rahman. He married a Czechoslovakian woman named Jarmila Fatma sometime during this period and the couple had a son named Omar. Siki’s last known match in Europe took place in June of 1941 in Prague. In December of that year, Germany declared war on the United States. The American civilians living within the empire were classified as enemy aliens and within months were arrested and sent to civilian interment camps where they were held as potential bargaining chips in prisoner exchanges. Siki and his family were taken into custody by German police in April of 1942.

Siki, along with several hundred other Americans, was imprisoned in Tittmoning, a 700-year-old castle located in south-eastern Bavaria. 8 The detainees at Tittmoning were classified as prisoners of war and subject to the rules of the Geneva Convention, though adherence to these rules was never guaranteed. “The Nazis kill people like flies,” Siki later told The Boston Globe. “Human life has no value to them.” There were days, Siki would later say, where so little food was given to prisoners that he would lie motionless to preserve his strength. Deliveries of supplies from the Red Cross were sometimes allowed and without them, Siki later said, “we would have been forever hungry, forever cold.”

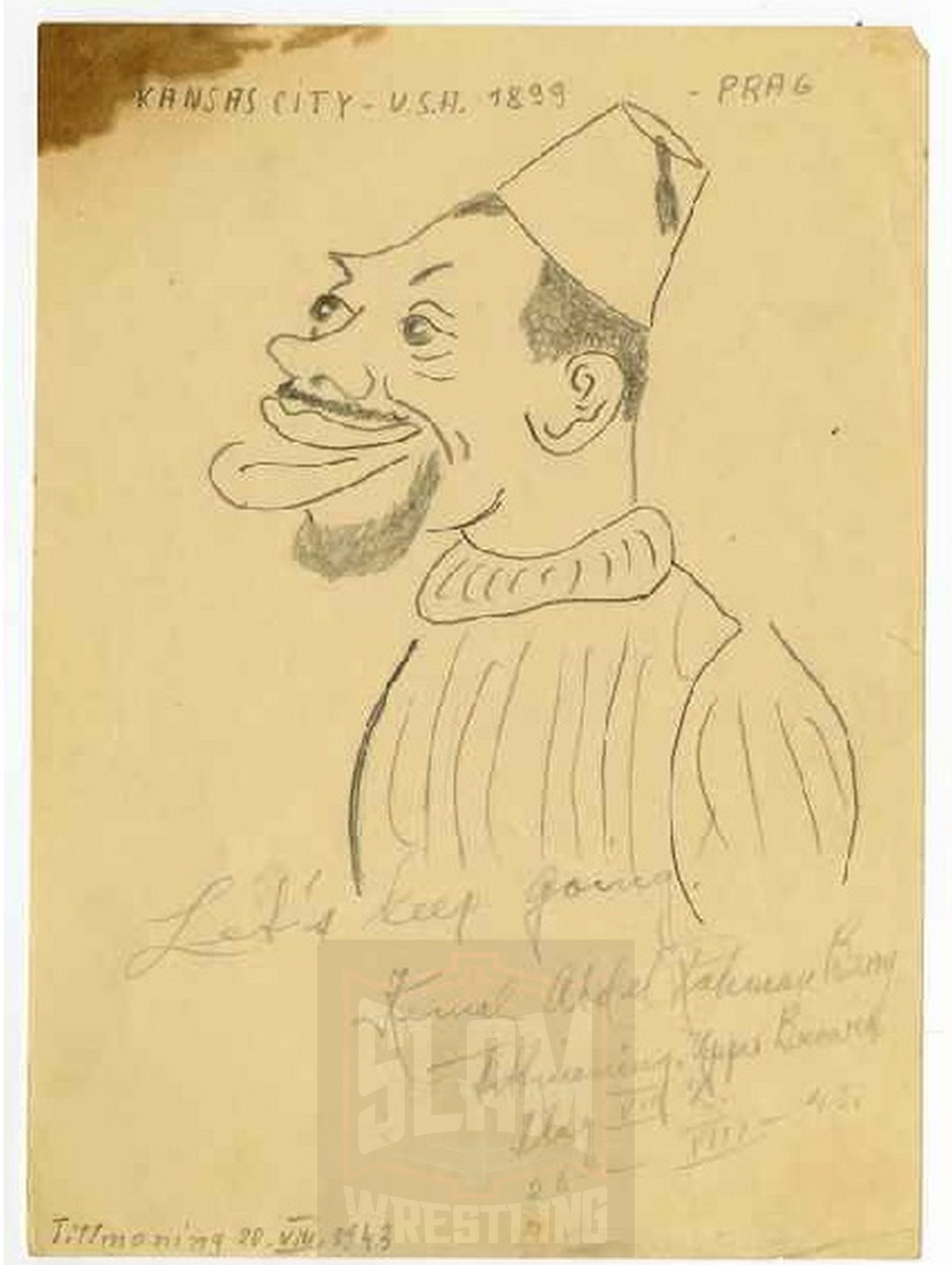

Caricature of Reginald Berry (Kemal Abdel Rahman) by Max Brandel. Gift of Jerome and Carolyn Mahrer, Museum of Jewish Heritage — A Living Memorial to the Holocaust.

During his imprisonment, Siki had a caricature of himself drawn by fellow prisoner Max Brandel, who would later become a significant contributor to Mad magazine. The picture was a gift to one of the camp’s young prisoners, Jerome Mahrer, who later donated the entire series of Brandel’s drawings to the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York. In the upper left corner Siki listed his place of birth and birth year. Below the drawing he included a note of encouragement for Mahrer: “Let’s keep going.”

Siki was released from Tittmoning in March of 1944, along with more than 300 other prisoners. As they were transported across Germany en route to meeting the Gripsholm, the Red Cross ocean liner that would return them to America, Siki looked in disbelief at the leveled German cities they passed through. “We saw Augsburg at dusk,” he told The Boston Globe. “It was three days after the Americans had bombed it. It was flat…really flat. Fires still smoldered in the ruins. The people stormed the train, trying to get out.”

He arrived back in the United States penniless. He settled in Boston, where promoter Paul Bowser had him working in matches at the Boston Garden by the end of the month. Now 44, Siki resumed a packed schedule of matches along the East Coast and into Canada. 9

His personal life remained complicated. His second wife, Jarmila, came to the United States in the early 1940s. His first wife, Ellen, was deported from Estonia and found work in New York as a nanny. In a 1946 interview with The Dayton Herald, Siki made reference to a possible third wife, named Sue, though nothing further about her is known. “[The United States] does not recognize religious marriages, only state marriages,” he told the reporter. “At the moment, I am a single man but I don’t know what to do about my two wives.”

In May of 1946, he wed his final wife, Mildred Strader, in a state-sanctioned ceremony in King County, Washington. The new couple moved to Los Angeles that summer, where Siki began an improbable second act in his career. He once again became a regular performer at the Olympic Auditorium, now working for promoter Johnny Doyle. The Olympic seated over 10,000 people and declared itself the “Largest Boxing and Wrestling Arena in the World.” Between September of 1946 and the summer of 1948, Siki appeared in multiple main event matches there. He had been in the wrestling business for over 20 years and was now performing for some of the largest crowds he’d ever seen.

Wrestling was booming in Los Angeles, bolstered in particular by the popularity of George Wagner, whose career fortunes had changed for the better after he began dying his hair blond, dressing in flowing capes sewn by his mother-in-law, and calling himself Gorgeous George. In November of 1947, George appeared on national television for the first time. The new medium helped him achieve a kind of success no other wrestler would experience until Hulk Hogan in the 1980s. “I don’t know if I was made for television,” George famously said, “or if television was made for me.”

Some seasoned wrestlers expressed bitterness over George’s sudden fame but if Siki shared their unhappiness he never let it be known. In fact, when a reliable veteran was needed to lose to George in a high-profile match at the Olympic, Siki took the job. On December 3, 1947, in a match that lasted just 12 seconds, he stood still while George came running towards him, leapt off his feet, and delivered a dropkick to his chin. Siki sold the move for the massive crowd right on cue, and collapsed to the mat.

The loss didn’t hurt Siki’s reputation, and he continued appearing at the Olympic weekly. His last known match there was on June 2, 1948 against Vic Holbrook, in front of a sold-out crowd. 10

Photo courtesy of Mark Brailsford

How Siki spent the last six months of his life is currently unknown. There are rumors that he had been seriously injured in a match, though they are unsubstantiated and unlikely to be true. In March of 1948, he had traveled to Texas and New Mexico for matches, and was clearly looking for new opportunities in the wrestling business despite being almost 50 years old. What might have happened had he lived can only be guessed at. Wrestling had become more fully integrated by then, with new performers like Jim “Black Panther” Mitchell and Seelie Samara working regularly. It’s likely Siki could have continued wrestling for another decade. Instead, on the morning of December 24, 1948, four days shy of his 49th birthday, he was taken to a hospital in Santa Monica, California suffering from a heart attack and declared dead on arrival. He was buried in Evergreen Cemetery, a short drive from the Olympic Auditorium, on December 31.

Reginald Siki never stopped moving. Despite harrowing odds and setbacks, he built a career in sports and traveled the world. Though much about him remains unknown, what is known points to a life rich in experiences. He was a pioneer in desegregating professional wrestling, and his contribution to the sport cannot be measured, even though it has been uncredited for almost 100 years.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Fantastic story! Thanks.

Thank you so much, Jon, for this wonderful recap of my grandfather’s life! I learned a lot. I watched a video quoting your story of my grandfather in the context of Black History Month. I had never thought of him as a historical figure.

Hi Mark! I am the great grandson of his last wife Mildred and we had pictures of him and them. Thsi story was so grreat!

Wow Jon, I can see you put in lots of time and hard work to put all this together. Good job!

Really enjoyed your article, Jon. Siki led a fascinating life.

Jon, I JUST came aross this article! I am the great grandson of his last wife MIldred Strader. Thank you for this!