When WrestleMania tees it up in San Francisco this Sunday, the most evocative nicknames that WWE’s creative geniuses can contrive will be on full display — the Viper, the Cerebral Assassin, the Lunatic Fringe and the Beast Incarnate.

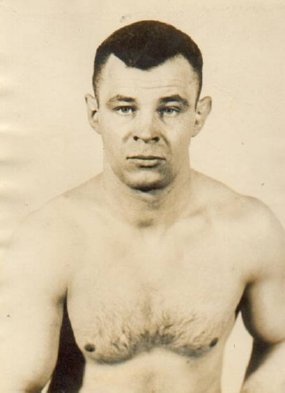

Joe Malcewicz

It’s safe to say there’s no room in that collection for Ol’ Waffle Ears. But that was an identifying tag for Joe Malcewicz, who helped to put San Francisco on top of the wrestling heap long before WrestleMania.

Malcewicz was a well-regarded wrestler for 20 years, known in part for his tangential involvement in a couple of world championship flaps. Then, he ran wrestling in the Bay Area for 25 years, parceling out stars like Ted Cox and Leo Nomellini to other promoters and winning acclaim as a fair guy in an often unfair business.

“I know he’s an honest, decent man, a substantial citizen who attends strictly to his own business, gives the public the best wrestling show available, is never mixed up in any off-color transactions and is, in every way, worthy of support,” Leo Dunbar of the Oakland Tribune wrote in 1944.

Malcewicz is attracting attention more than 50 years after his death because he’s part of the Hall of Fame Class of 2015. That’s not the WWE Hall of Fame, which holds its annual ceremony this weekend, but the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in Amsterdam, N.Y. He was elected in the Pioneer Era and will be added to the hall’s rolls in May.

All in all, not bad for someone whose grappling education began in the basement of Christian Brothers School in Utica, N.Y., with impromptu lessons from a wrestler-turned-school janitor.

“Of all the big names who helped packed the Auditorium off and on, I always considered Malcewicz No. 1 THE wrestler despite the fact that he did not fit the pattern of champion as decreed by the powers that be,” said Lloyd Larson of the Milwaukee Sentinel.

In 1917.

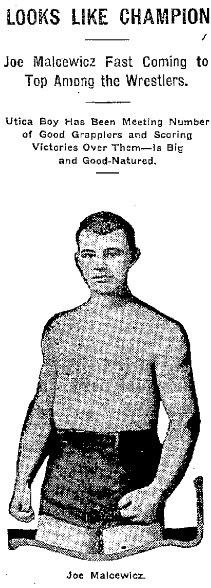

THE UTICA PANTHER

The son of Polish immigrants, Malcewicz was born March 17, 1897 in Utica, the oldest of five children. While he picked up on wrestling as a teenager, he also played football at Utica Free Academy and for the Utica Knights of Columbus. Working at his dad’s grocery during the day, he started wrestling as a light-heavyweight in upstate New York at night. His earliest recorded match was a draw with Charles Uberle on Feb. 2, 1914 in Utica, though he probably had some pro bouts before that.

Trained by the legendary Farmer Burns and Englishman Herbert Hartley, Malcewicz at 6-foot-1 and 200 pounds progressed quickly and split a series of well-received contests with future great Jim Londos in Canton, Ohio, in 1917. World War I interrupted his rise; he served a stint in the military at Camp Jackson, S.C., reaching the level of sergeant before returning to wrestling.

According to researcher par excellence Don Luce, Malcewicz stayed close to his home base during the early 1920s, always wrestling in bare feet and winning acclaim as the “Utica Panther.” Utica was the site of his first world title claim, one that became more exaggerated as his career advanced.

Wrestling lore holds that the hometown kid upset champion Earl Caddock by decision in a 90-minute bout in Utica in 1920. But wrestling’s ruling czars jobbed him out of his accomplishment when they pledged allegiance to Joe Stecher, who beat Caddock in a subsequent bout in New York City.

In 1924.

“By any sort of test Joe Malcewicz was the world’s heavyweight champion, but neither he nor the men handling him were shrewd enough to set up a country-wide howl that Joe had corralled Caddock’s title,” James Hurley recounted in the popular American Legion Monthly in 1932.

The uncrowned champ angle made for good promotional copy. But the facts don’t back it up. Malcewicz actually squared off with Caddock on Jan. 14, 1921, after the title switched to Stecher. Neither wrestler scored a fall and referee Jack Winrow awarded the match to Malcewicz on the ground that he had escaped more holds.

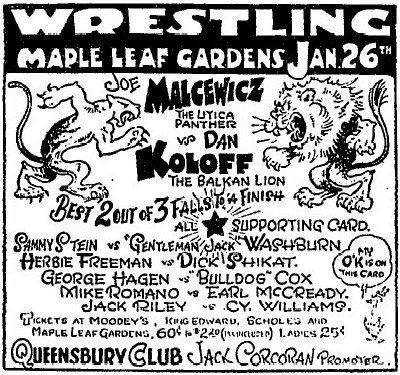

Headlining at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens. Courtesy GaryWill.com

DOUBLE CROSS IN BOSTON

Five years later, Malcewicz again got within sniffing distance of championship glory. He had developed his skills as a shooter and was a featured performer for promoter Paul Bowser in Boston.

A major player in the syndicate wars of the 1920s, Bowser wooed Stecher to Boston for a reported $12,500 to face an unnamed opponent. The Stecher camp, which included brother/manager Tony and New York impresario Jack Curley, assumed the opponent would be a friendly foe from Iowa named Jack Brissler. Brissler entered the ring, but he exited just as quickly when Malcewicz, sitting ringside in street attire, slid under the ropes.

The champ took one look at Malcewicz, deduced that he was on the wrong end of a double cross, left the ring and said he’d return only for a side bet of $10,000. Meanwhile, Malcewicz beat Ned McGuire and was announced as the new titleholder by default.

“Joe had been coming along in a sensational style and had been a popular favorite with Boston fans,” Bowser later explained. “Oh, boy, what a rumpus in the arena. You should have heard the crowd yelling. For a while, I thought a regular riot would break out, but we finally managed to quiet things down and go ahead with a substitute match. … Malcewicz would have defeated Stecher that night.”

Unsurprisingly, Malcewicz’s title assertion didn’t stick. Curley and Bowser settled their scores long enough to get Stecher and Malcewicz in the ring a few times.

But Bowser’s guidance helped Malcewicz become a national drawing card, as he went through 1926 and 1927 virtually undefeated, save a couple of contests with Ed “Strangler” Lewis. One bout with the Strangler was a three-hour, 22-minute draw on July 1, 1926 in front of about 10,000 fans at Braves Field in Boston.

“The lack of proper management is believed to have kept the Utica mat star from being a topnotcher several years ago and not until Paul Bowser took over the reins was his real ability discovered. In a little less than one year Malcewicz proved the biggest sensation in the mat sport under the direction of his new manager,” the Syracuse Herald opined in 1926.

But he wouldn’t get any closer to holding a world championship despite the fact that Lewis in 1948 placed Malcewicz on the same plane as Caddock, Ad Santel and John Pesek, three greats of the ring.

In 1926.

That’s because Malcewicz was limited not just by the politics of the business, but by his own workmanlike and serious style. He was a no-frills wrestler in black trunks, not given to histrionics and style over substance. Milwaukee scribe Larson thought he was an ideal “policeman,” shorthand for a wrestler who would take out any uppity pretender who got out of line.

“Malcewicz was a heavyweight wrestler who could twist an opponent with the sinuosity of a boa constrictor, snapping bones were he so inclined,” said California sportswriter Alan Ward. “There is no evidence Joe maimed an opponent, and he wrestled the great and the mediocre — for the most part during an era before wrestling had deteriorated into buffoonery.”

CAREER CHANGE

By the early 1930s, Malcewicz was just below the top of the wrestling pecking order, credibly challenging but always losing to Londos, Jim Browning, Gus Sonnenberg and other champs of the time. Settling in northern California, he was billed as the Pacific Coast champion against opponents such as Matros Kirilenko.

When Bowser came calling with a business proposition, Malcewicz hung up his boots at the relatively young age of 38. Nudging promoter Jack Ganson out of the way, they took over the bookings in San Francisco and a bevy of outlying towns. Malcewicz also got help from Lou Daro, the larger-than-life promoter in Los Angeles, who provided him with talent in return for a 50 percent cut of profits and a five percent public relations fee.

In time, Malcewicz didn’t require outside assistance, though he had to fend off state-run investigations of the wrestling racket. He briefly had his license to run the San Francisco auditorium pulled in 1939 amid allegations of payoffs to helpful sportswriters.

As a promoter, he wasn’t above innovation; in 1944, he and brother Frank fabricated a round, 18-foot-wide ring as an alternative to the squared circle. Malcewicz’s world tag team title, dominated by Ben and Mike Sharpe, was the most accepted version of the crown in the early 1950s. And he was always on the lookout for crossover athletes, trying to make wrestlers out of strongman Doug Hepburn and footballers Art “Boom Boom” Mihalik and “Big Daddy” Gene Lipscomb.

Frank and Joe Malcewicz make plans. Courtesy Crowbar Press

By far, Malcewicz’s most successful project and the one that sent San Francisco into a wrestling tizzy was Leo Nomellini, a 287-pound defensive tackle for the 49ers who had been a standout heavyweight wrestler at the University of Minnesota.

Nomellini started wrestling in the football off-season in 1951. By 1953, he emerged as a credible challenger to Lou Thesz, the National Wrestling Alliance World champion. On June 16, 1953, the two fought to a sensational draw in front of a record wrestling crowd of 16,487 at the San Francisco Cow Palace.

Fast forward two years and Nomellini was embroiled in a world title dustup just like his mentor with Caddock and Stecher. On March 22, Nomellini apparently won the NWA belt when referee Mike Mazurki disqualified Thesz in the third fall of a match in San Francisco.

Thesz repeatedly kicked Nomellini to the floor as he tried to re-enter the ring, which Mazurki and Malcewicz contended violated state athletic commission rules. In opposition, the NWA insisted the championship would stay with Thesz because world titles could not change hands on a DQ.

It was, in wrestling parlance, a work. A careful review of NWA documents by Tim Hornbaker and other experts has revealed the alliance was plotting a title schism angle trumpeting both Thesz and Nomellini as world champs.

NWA President Sam Muchnick started booking Thesz and Nomellini as champions — Muchnick got two percent of Nomellini’s appearance earnings, with another two percent to Malcewicz. The NWA out-thought itself, though. The competing claims didn’t do much at the box office and Thesz beat Nomellini once and for all in July 1955 in St. Louis.

As his cauliflower ears grew to such proportions that Ward suggested they be imprinted in soft cement near Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, Malcewicz reflected on the difficulty of balancing serious wrestling with sports entertainment.

“We give the public only what it demands,” he said in 1956 after a state investigator suggested deregulating wrestling in California. “If the fans wanted strictly scientific wrestling, with matches lasting two or three hours and with neither grappler willing to take bold chances, they could have it. They want showmanship and drama and a touch of ham. Yes, and some comedy and a great deal of physical perfection.”

By 1960, though, Malcewicz’s shows weren’t showy enough. Roy Shire, learning from Jim Barnett and Johnny Doyle in Indianapolis, started running cards at military hospitals and bases in San Francisco, then rebroadcasting them on TV. Malcewicz fiercely opposed Shire’s bid for a license to promote TV and live shows in the San Francisco territory.

“I am not protesting a wrestling show, but the televising of the shows,” he insisted, saying TV wrestling had diluted the business in Boston, Philadelphia and Minneapolis by keeping fans at home instead of in the arenas.

In 1961, Malcewicz gave in to modernity, running televised shows on Monday nights on Channel 2 in San Francisco. It was too little, too late, though, because Shire had better talent, namely Ray Stevens, at his disposal.

“See, Joe used the heavyweights and they were kind of slow moving and Ray Stevens went out and bounced all over the place and got over, with that bleach blonde hair,” recalled Frankie Cain.

In November 1961, Malcewicz announced he would join George Parnassus of Los Angeles and Lou Thomas of San Francisco in a new sports promotion, but he effectively ceded the wrestling territory to Shire. Five months later, he suffered a fatal heart attack while trimming a hedge at his San Francisco home. He died April 20, 1962 at the age of 65.

Malcewicz “had a chuckling sense of humor, two of the most impressive cauliflower ears in existence and a soft voice,” Ward wrote in memoriam. “He had an inconspicuous way of doing thoughtful favors for friends and acquaintances.”

He still does. The Joe and Emily Malcewicz Scholarship for outstanding academic achievement is awarded annually at the University of San Francisco.

PWHF CLASS OF 2015

-Pioneer Era (1800-1946) – Joe Malcewicz and Great Gama (Ghulam Muhammad)

-Television Era (1943-1984) – Pedro Morales and Whipper Billy Watson

-Modern Era (1985 – present) – Curt Hennig and Rick Martel

-Ladies – Vivian Vachon

-Tag Team – The Fabulous Freebirds (Michael Hayes, Buddy Roberts and Terry Gordy)

-Colleague – Jim Crockett Sr.

-International – Tomomi “Jumbo” Tsuruta

RELATED LINK