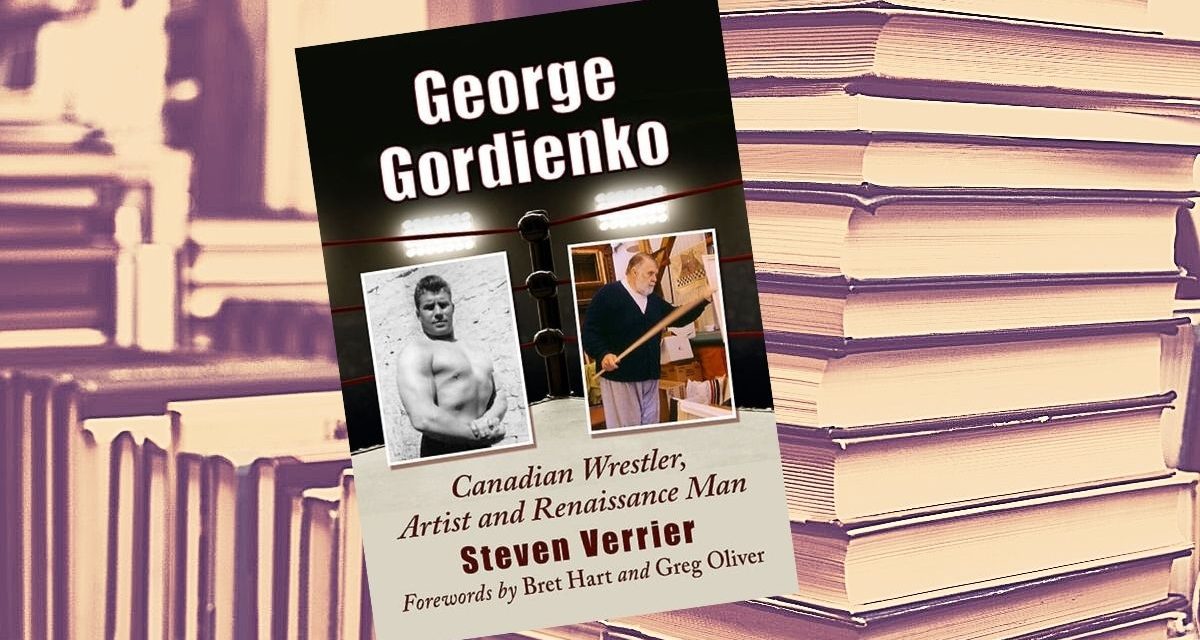

George Gordienko might very well be the greatest wrestler you have never heard of. As an American wrestling fan (and writer), it’s somewhat embarrassing to admit I knew little about the man. Beyond the occasional reference to Canadian match results and the high esteem he was held by major names like Bret Hart (who also penned one of the book’s forewords, along with SlamWrestling’s own Greg Oliver), the name meant nothing to me. However, thanks to George Gordienko: Canadian Wrestler, Artist, and Renaissance Man, I have seen the light.

Just how impressive was George Gordienko, the man? From being handpicked for the NWA World Heavyweight Championship by none other than Lou Thesz to going toe-to-toe with Spiros Arion in Greece to headlining in Baghdad against Adnan Al-Kaissie, Iraqi hero, at the packed Al-Shaab Stadium, Gordienko’s legacy is truly impressive. (READ MORE: Thesz wanted Gordienko, not Watson, to win NWA title in 1956)

In George Gordienko, Steven Verrier expertly weaves these unique stories into the narrative, providing an excellent entryway for casual fans to dive deeper into the world of international wrestling. All the greats of yesteryear are present, including Spiros Arion, Wayne Bridges, Karl Gotch, and more, along with some names that might not immediately stand out (such as Michiharu Toyonobroi, trainer of the legendary Rusher Kimura).

What sets George Gordienko’s life apart from so many of the greats mentioned above is the political interference he faced. Having built up his name working with the likes of Stu Hart and Tony Stecher, Gordienko found himself shut out of American wrestling due to the rampant anticommunist sentiments of McCarthyism in the 1950s. For those unfamiliar with the period, McCarthyism was a period of communist witch hunts carried out under US Senator Joseph McCarthy, with many of those impacted facing an effective ban from living, working, or even visiting the United States.

The near-global respect for Gordienko stands in stark relief to the nearly invisible status the great man has in the United States. But this darkness is a testament to the derisory party politics of McCarthyism — and the immense international reputation of Gordienko is a testament to a truly world-class, revolutionary athlete.

Gordienko not only took on the greatest wrestlers the world had to offer, no matter the country or the code, but he actively walked into the toughest training dens to test his mettle and establish a massive legacy (like the feared Snake Pit in Wigan).

Here’s George Gordienko in action against Paul LeDuc:

A big concern with dealing with the now semi-mythical hookers like Gordienko, Gotch, or John Pesek from an earlier era, is falling into the trap of ignoring the man and idolizing the legends.

Gordienko’s story — and Verrier’s telling — is a fascinating journey through the colorful world of wrestling. The Winnipeg, Manitoba-born grappler faced immense political persecution and was forced to turn away from the sure money of US TV wrestling. And instead of wilting, he built a legacy from the ground up in countries spanning the globe. Such an impressive tale could lend itself to mythologizing in the retelling. Despite that, Verrier avoids hero worship, providing a nuanced, balanced, and thoroughly-researched picture of a complicated man.

All the stories are here, from grappling with hookers like Thesz, Stu Hart, or Luther Lindsey, to selling out stadiums (in Greece, with Spiros Arion, in New Zealand, and later, in Baghdad). The latter story is fascinating and details the famed match between Gordienko and Iraqi wrestler Adnan al-Kassie. The Al-Kassie story is particularly enlightening, as I knew very little of the event, minus the brief mentions in shoot interviews throughout the years.

If the stories of Gordienko’s successes are impressive, his contemporary legacy amongst the wrestlers and fans is mind-boggling. The treatment Gordienko received worldwide is a testament to the abilities of a man often considered a peer with Lou Thesz, Billy Robinson, Karl Gotch, and many of the other famed hookers of the era. Not only that, but Gordienko was placed on the same level as major international draws Don Leo Jonathon and Andre the Giant. For the novice wrestling fan, that may sound nice. Still, any expert can tell you that those names are held in the absolute highest of regards globally — again highlighting Gordienko’s unsurpassed skills.

If there were a criticism of the book, it would have to be the heavy-handedness of Verrier’s treatment of Gordienko’s early life, including his athletic prowess. The latter part of the man’s athletic life is of primary interest, not his early teen rugby achievements. Again, this criticism is rather a matter of personal preference, and not an indictment of Verrier’s skills as a historian.

If the early treatment of Gordienko’s childhood feats felt slightly long, the discussion of the man’s early association with the Communist Party is essential reading. Beyond introducing another dimension to this complicated man, it also reminds the reader of the divisive politics of mid-century America, with Gordienko one of its lesser-discussed victims.

But George Gordienko was far more than just a once-in-a-generation wrestling talent. Beyond his wrestling credentials, Gordienko also excelled in the world of art. A member of the Ontario Society of Artists and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, he also went merely creating art, teaching at an impressive selection of institutions, including the Ontario College of Art and the University of Toronto.

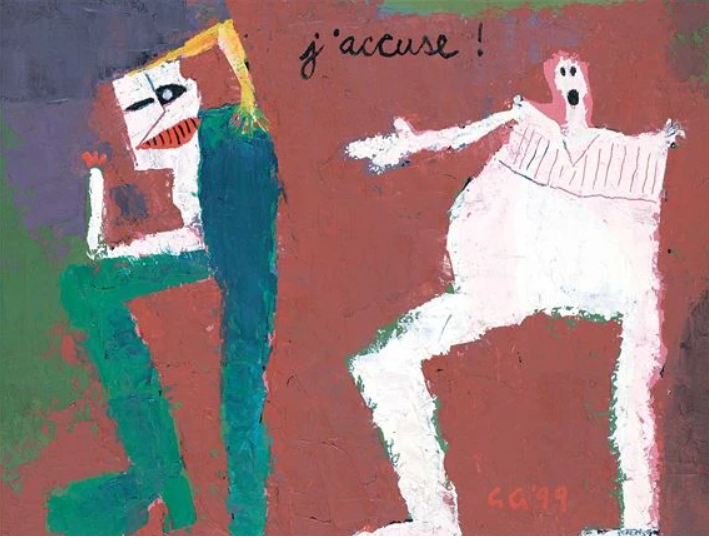

Gordienko’s style and subject matter were heavily influenced by the art movements of the 20th century, particularly Surrealism and Expressionism. His bold, expressive brushwork and vibrant colors reflected these movements’ influence, and his subject matter often reflected a sense of emotion and movement. This artistic influence was likely heightened thanks to his extended international travels.

Gordienko’s art often depicted figures in dramatic poses and used vibrant, expressive colors to convey a sense of energy and movement, such as the harlequin-inspired, dramatic piece J’accuse (pictured).

George Gordienko’s J’Accuse.

Ultimately, George Gordienko: Canadian Wrestler, Artist, and Renaissance Man (McFarland Books), is an essential read for anyone who loves Canadian, British, or European wrestling history. Verrier not only introduces us to Gordienko but also helps us understand why legends like Bret Hart consider Gordienko to be one of the all-time greats, despite what mainstream wrestling dictates.

Verrier’s book goes a long way to not only demonstrate the fearsome skills of the Canadian grappler but also provides an excellent introduction to some of the premier wrestlers of the era, grapplers that might have otherwise fallen through the historical cracks. Combine that with fascinating discussions on politics and art, and you have a complex picture of an equally complex man. With “artistic” wrestlers like Cody Rhodes and Kenny Omega enjoying a renaissance, perhaps George is finally about to have his day.

RELATED LINKS

- Apr. 28, 2022: BC police on hunt for stolen Gordienko art

- Apr. 25, 2022: Gordienko was destined to be an artist

- Jan. 17, 2022: Thesz wanted Gordienko, not Watson, to win NWA title in 1956

- Jan. 10, 2022: Gordienko: Canada’s top wrestler worldwide from the 1950s-1970s

- May 12, 2004: Nephew aims to boost Gordienko’s legacy

- The Artistic Canvas section

- Buy George Gordienko: Canadian Wrestler, Artist and Renaissance Man at Amazon.com or Amazon.ca

George was without a doubt one of the truly underrated wrestlers.