Billy Robinson, one of the toughest men to ever lace up wrestling boots, has died. He was 74.

His biographer, Jake Shannon, with whom he collaborated on Physical Chess: My Life in Catch-as-Catch-Can Wrestling, confirmed the passing.

“I am unbelievably sad to report that my very good friend Billy Robinson has passed away,” wrote Shannon on Facebook. “I hadn’t heard from him in days so I contacted his apartment complex to check in on him. When I called back for a progress report the apartment manager put the police on the phone, it seems he passed peacefully in his sleep. He was a lion of a man, bigger than life in so many ways, my wife and I named our youngest son, Lliam, in his honor. You will be sorely missed, my friend. Thank you so much for living the life you did.”

Robinson was born in Manchester, England, in September 1939, and there was a real sports pedigree in his family — his great-grandfather was Harry Robinson, a bareknuckles boxing champion; his uncle, Alf, fought Max Baer and wrestled Jack Sherry, in Belgium; and his father, Harry, was a light-heavyweight boxer. He seemed destined to become a boxer as well, until he injured his eye at age 11 and was unable to ever get licensed. At 15, he started heading to Wigan from Manchester, where he worked in a wholesale fruit market, the biggest one in England, moving crates and bags of potatoes.

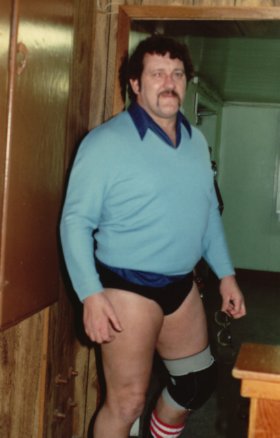

Billy Robinson. Photo by Terry Dart

But the main attraction in Wigan was the Snake Pit, a famed training ground.

Wigan’s Snake Pit was the result of Great Britain’s colonial history, said Robinson. “You had the greatest wrestlers of all time in that gym, basically caused by the British Navy. They went around the world, controlled most of the world for hundreds of years, and picked up stuff from all over the world and united it into one submission sport. When you got to the gym, all the oldtimers would be there watching. If it was one of the oldtimers, it was probably an ex-world champion, and if he took a liking to you, he’d pull you to one side and say, ‘Try this, son, try that; don’t do this, and don’t do that.’ It was just a great way to learn. They didn’t teach you how to wrestle, they taught you how to learn.”

In 1960, he made his pro wrestling debut and quickly built a serious reputation. “Billy was one of a number of fighters who would never allow himself to be defeated unless he was convinced that man was capable of beating him,” wrote the late Jackie “Mr. TV” Pallo in his autobiography. “A really gentle gentleman outside the ring, is Billy. But he could be a bit vicious inside it.” He was constantly looking for a challenge said Frank Earl. “He used to go around the dressing room and ask people, he said to Les Thornton and I, ‘I hear you can block a bit.’ I said, ‘Yeah, not bad.’ He said, ‘Why don’t you work with me?'”

In 1969, after meeting Dave Ruhl in Japan, he left for Calgary, still the British Empire champion, where he was a hit. “His repertoire of quasi-amateur moves, such as suplexes and saltows, combined with the high-tech Euro style, made for a compelling hybrid — the likes of which fans in our neck of the woods had never been exposed to before and were captivated by,” wrote Bruce Hart. But Calgary was where his reputation for being difficult to work with multiplied. Archie Gouldie walked out of the territory, giving up an NWA World title shot, rather than work with Robinson.

“He wanted everyone in the world to think that wrestling was real because of his background,” said Calgary headliner Dan Kroffat. “I hated the guy. He was a bully. He was an antagonistic sort of guy, he bullied guys, he stretched guy. He was really not a likeable guy. Then Robinson, if he had respect for guys who were shooters, of course he would give them great matches. He went to Minnesota where Verne Gagne was a shooter. He fit right in to Verne Gagne’s thinking. But in Calgary, Jesus, nobody wanted to work with him. I had him seven nights in a row. It was the closest I ever came to quitting the business in my life. He just stretched me night after night.”

Robinson will admit that he would shut down opponents he felt were unworthy of his talents. “Normally, it was the guys that were just showmen that were scared to death to get in the ring with me. It used to take me five minutes to 10 minutes to get them at ease so they’d work,” he said. If they were scared to work with him, too bad. “That’s their fault, not mine. I’ve never been scared of anybody. None of the guys from Wigan ever were.”

After Calgary, Robinson spent two years in and out of Hawaii, and met Verne Gagne there, and the AWA promoter invited him to Minneapolis. There, Robinson was a genuine headliner, allowed to work with foes that could perform his style. “He was one of the real fine technicians. He was great on submission holds,” said Gagne in 1994.

Besides his success in North America, Robinson is close to a deity in Japan, where he did countless tours, was the first ever International Wrestling Alliance World champion, battled Antonio Inoki in a massive 1975 contest, and is a respected trainer. Karl Gotch was his entry into Japan, though the promoters didn’t know that Gotch and Robinson’s uncle had been great friends, and that Billy saw Gotch as an uncle. But that doesn’t mean they always got along, stressed Robinson. “We had our differences, but we worked it out in the gym. … if it had been in public, it would have been a street fight and we both would have been arrested.”

Robinson’s real fights are a big part of wrestling lore. The Rock likes to tell the story of his grandfather, Peter Maivia, brawling with Robinson in Japan in 1968, falsely crediting the High Chief for Robinson’s eye loss. Then there’s the brawl with “Sailor” Ed White in the ’70s. “Sailor White beat the shit out of him and pissed on him — and Billy Robinson was supposed to be THE shooter,” said Frenchy Martin. “Everybody thought he was a shooter, but once Sailor White beat him up, that was it. He had to go, and he left.”

Robinson was always great friends with Lou Thesz, who always championed bringing legitimacy back to professional wrestling. Together, they started the United Wrestling Federation. “Billy is a competitor to the core. It was his best asset and his worst enemy. He had to push himself and make everyone he wrestled look as bad as possible. Winning wasn’t enough, Billy was into destruction,” said Thesz in 1997, adding that he had “ultimate respect for his ability and spirit,” and that “he is also more fun than a barrel of Aussies.”

In North America, Robinson’s career petered out in the early 1980s, just before the cartoonish WWF took off. “I’m a real wrestler. I believe in real wrestling. I believe in catch-as-catch-can wrestling. The show wrestling now has become pathetic. It’s a complete show, and I just won’t have anything to do with it,” he said.

Instead, backed by trainer/author Jake Shannon, Robinson carved out a living over the last number of years as a guest trainer at seminars from Japan to London, from Montreal to his regulars in Little Rock, Arkansas, where he lived near his son, Colonel Spencer Robinson, who works at Camp Joseph T. Robinson, the 33,000-acre training facility of the Army National Guard. Billy Robinson made occasional appearances at fan fests, and was inducted into the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2011.

RELATED LINKS

- Mar. 17, 2014: Harry Smith remembers Billy Robinson

- Sep. 2011: Billy Robinson memoir out in Spring 2012