As great a wrestler as George Gordienko was, there probably wasn’t a time in his life, from elementary school on, that he didn’t consider himself, above all else, an artist. His skill as a wrestler couldn’t be denied, and he used that skill—and the demand for his services as a wrestler worldwide—as a ticket to see the world and to store experiences that he could apply to his life as a full-time artist after he left wrestling in 1975. But from the time he was a boy growing up in the Depression in North Winnipeg, there were clear signs that being an artist was his ultimate calling in life.

A neighbor of the Gordienko family, Edward Barris, shed some light on George’s early years in a 2005 interview with George’s nephew Ted Gordienko. Barris, who lived down the block from the Gordienko home on Parr St. in North Winnipeg, recalled visiting the Gordienkos in the mid-1930s, when George was about seven or eight years old.

“Everybody was busy,” he said. “They had borrowed a Monopoly set, and then they were copying it. George was drawing the board, painting it, and somebody else was making the money. They did a hell of a good job. Another one carved the … little pieces you move. … I remember George drawing the pictures and then painting them, and, you know, the thing looked like a real Monopoly set when it was finished.”

Barris also recalled how Gordienko had shown an aptitude for art early in life when “one of [George’s elementary school] teachers was having a bridge party, and she had George draw police cars for every one of the players. He would draw pictures and he painted them all for the teacher, and she was quite pleased with them, I remember. He was very good. He was recognized as a good drawer.”

The Depression years weren’t easy for the Gordienkos, as George’s father Feodor was laid off from his full-time job with Manitoba Bridge and Engineering and the family went without a steady paycheck for several years. But when Feodor was called back to his job after World War II broke out, the first special gift he bought George—the first thing George, then 12 years old, said he wanted—was a kit of art supplies.

The extent of any early art training George may have received in Winnipeg is unknown, though it’s clear that he tried to paint as much as he could when he wasn’t busy playing high school football, setting national records in weightlifting and gaining recognition as a top amateur wrestler, and engaging in various other athletic activities ranging from soccer to swimming to shot put. It appears, though, that he had some art instruction in Winnipeg in 1945 or 1946, at the height of his success in amateur sports not long before he debuted as a professional wrestler in late 1946.

Gordienko had a busy schedule of matches and training while based in Minnesota during the early part of his pro wrestling career. But while based in San Francisco for several months in 1947, he managed to take some art lessons and found a little time to paint on the side. A year later he was out of wrestling for what would be a four-year hiatus, during which time he worked at various jobs and continued to develop his techniques as an artist before getting back into the ring in Western Canada for a strong run that lasted about a year and a half.

George Gordienko attended the City & Guilds of London Art School (thanks to Ted Gordienko).

After finishing a tour of Australia in 1954, Gordienko took another break from wrestling and traveled by sea to Italy, where he took in some of that country’s artistic treasures before heading for the United Kingdom, where he studied art in London for several months during the fall and winter of 1954-1955. At the school he attended, Saint Martin’s School of Art—one of several leading art institutes Gordienko would attend over the years—he studied under Anthony Caro, who influenced a generation of British sculptors and went on to become one of the leading abstract sculptors of his age.

George Gordienko attended the Saint Martin’s School of Art in London (thanks to Ted Gordienko).

Gordienko returned to Canada and spent most of 1955 and all of 1956 wrestling in Western Canada before travelling back to the United Kingdom in early 1957. For most of the remainder of his wrestling career he was based in the UK, where he maintained connections with the art community in London and continued to improve his techniques, experiment a bit, and develop his skills as an artist while he made his living as a wrestler. Among his friends in London were well-known Canadian artists Bruno and Molly Bobak, who ended up living for a time in the house Gordienko bought in Streatham, London. Gordienko often took in renters—the majority of them wrestlers—in various rooms in his large house, but one room was off-limits to everyone but Gordienko. That room was his art studio, where he was known to disappear for days at a time when he didn’t have any wrestling appearances scheduled.

Gordienko’s housemates were well aware of his attraction to painting and to art in general, even though it was still a hobby at that point. Mary Nelson recalls, of Gordienko’s painting while she and her husband Gordon Nelson—a grappler from Winnipeg and Gordienko’s best friend at the time—were living at Gordienko’s home in the 1960s, “It was dark and gloomy. … I don’t know how to explain his art work.”

But Gordienko showed surprising range, she says, when he did a painting of the Nelsons’ infant son Steve, who was born in 1965. She says, “[It was] almost like a six-foot canvas. … It was like somebody took a picture of him.”

Although Gordienko lacked the confidence and any serious inclination to try making art his primary source of income at that time, art was probably established as his primary source of satisfaction. He’d shown the curiosity and insightful awareness of an artist from his early years, and it’s reasonable to say that his physical gifts—which brought him fame in numerous countries and a degree of financial health that would have been hard to match in the art world—were actually a curse that kept him from fully pursuing his truest calling while he was in his physical prime. But clearly, while Gordienko, even with some excellent training under his belt, likely would have called himself a recreational artist when he was in his late thirties in the mid-1960s, artistic creation was something he seemed compelled or destined to do.

Gordienko began spending much of his time in Italy in the early 1970s, and it wasn’t long until his work started getting exhibited in his new home base. When he was in Canada in 1972 following a tour of Japan—where he made a point of checking out various art galleries, as was his habit during his travels throughout his wrestling career—he told Garry Allison of the Lethbridge Herald in a Nov. 28 feature, “My art has reached the stage where any doubts or insecurities I had are behind me. … I know what my clientele wants and that’s what I paint.” Of his work—which would noticeably become more experimental in later years—he added, “It’s not abstract and yet my paintings are not of the classic nature either.”

That somewhat subdued approach to his art seemed to stay with Gordienko after he completed his transition to life as a full-time artist after hanging up his wrestling boots in 1975. He knew the transition wouldn’t be easy, and he was careful not to jeopardize his chances of success by focusing more on what he wanted out of art than on what the buying public wanted. Over the years Gordienko had received some first-rate instruction in painting, sculpting, and printmaking, and from his base in northern Italy he seemed more intent on displaying his solid technical skills than on pursuing what may have been perceived as a more presumptuous route for someone at that stage of his career.

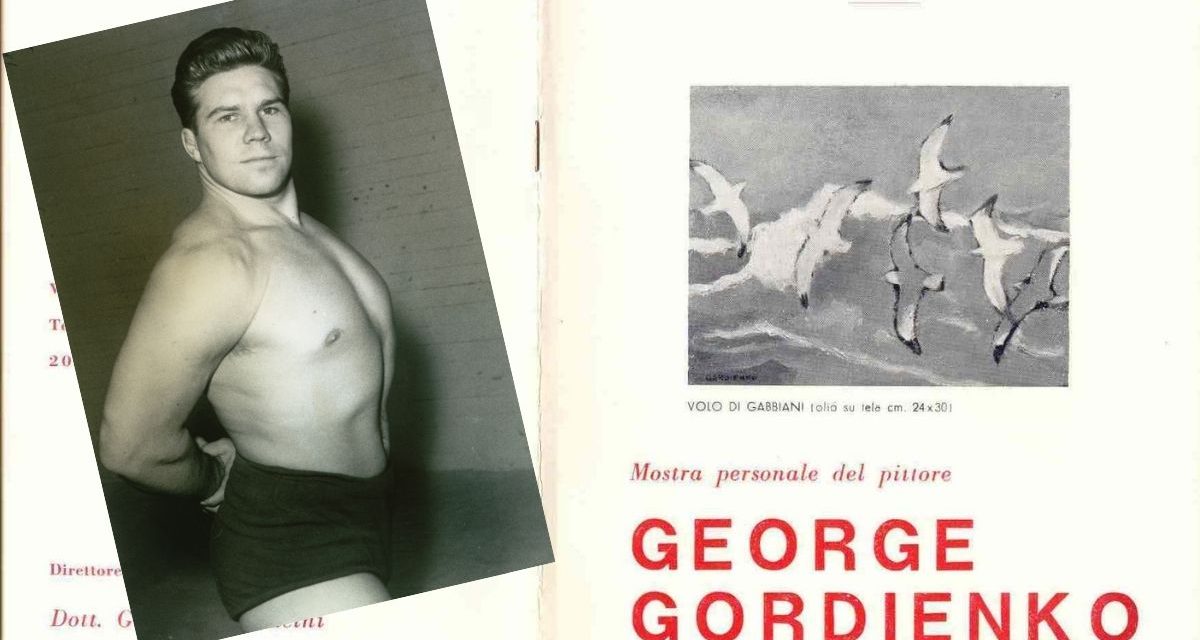

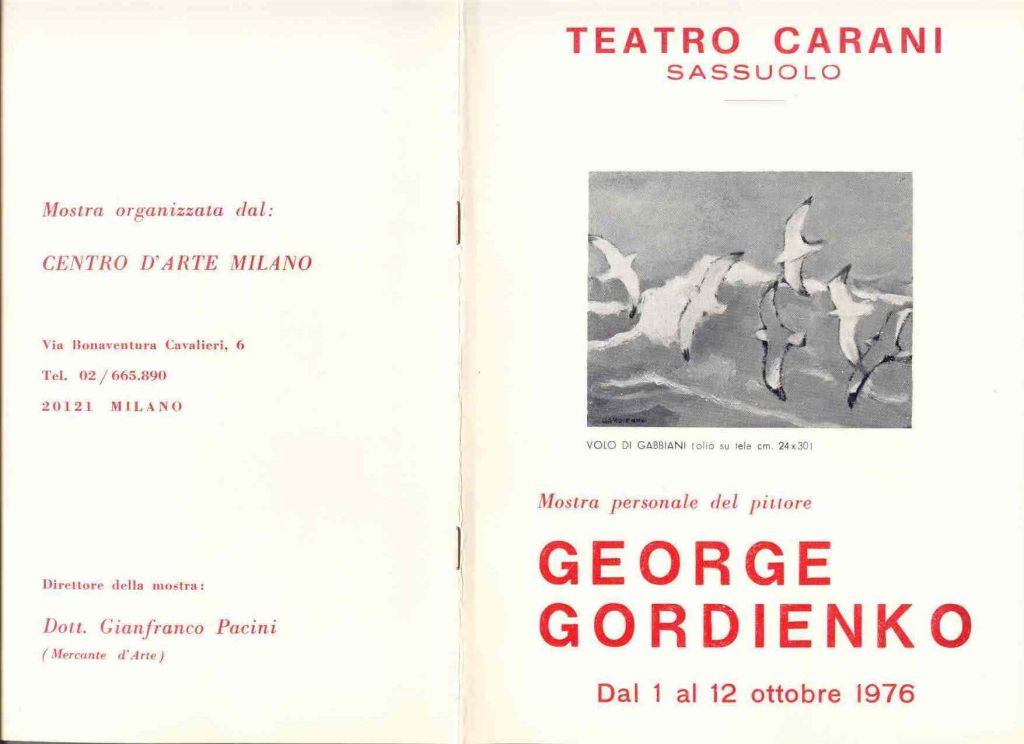

Early in his career as a full-time artist, Gordienko’s training and skill earned him some recognition in his adopted home of Italy, where he lived and exhibited his work for many years (thanks to Ted Gordienko).

Years later, British Columbia art gallery curator Peter Redpath, speaking of Gordienko’s time in Italy following his departure from wrestling, told Ted Gordienko, “His work there was quite restrained. … Market conditions held him back from exploring a more surrealist avenue, which was intriguing to him.”

Aside from logging some sales in Italy during his first full years as a full-time artist in 1976 and 1977, George Gordienko also did some travelling in Europe, particularly back to England and Spain, partly to do some painting but also to mingle with other artists and to learn new tricks of the trade, much as he’d done over the years as a world-travelling wrestler. Then, apparently at some point in 1977, he made a trip back to Winnipeg, where his journey as an artist had begun.

The occasion for Gordienko’s 1977 return to Western Canada was apparently the declining health of his father Feodor, who, 37 years earlier, had given George his first art supplies, effectively giving his blessing to George’s choice of a lifelong vocation. Several weeks after Feodor passed away in late January 1978, Gordienko turned up in Atlantic Canada for a milestone event in his life—his first art exhibition in his native country, held at the University of New Brunswick arts center in association with his friends Bruno and Molly Bobak. It appears the exhibition was heavy on still lifes, portraits, and other works of a realistic, market-conscious nature as Gordienko apparently aimed to introduce himself to a new audience in his native country as a trained artist whose work could be taken seriously.

Later that year, Gordienko had another exhibition in Canada, this time in his hometown of Winnipeg at Eaton’s Galley of Fine Art. A Dec. 4, 1978, Winnipeg Free Press ad inviting the public to “Come meet Canadian artist George Gordienko” and making no mention of his history as a wrestler said, “He does exquisite flowers, fruit, landscapes, and people in oil, and delightful black and white drawings.” Reporting on the week-long Gordienko exhibition in the Dec. 14, 1978, Winnipeg Tribune, Cathy Schaffter—who made much in her article of Gordienko’s life as a wrestler—wrote, “Gordienko’s still-lifes and figure paintings are on view at Eaton’s Fine Art Gallery until Friday. And there’s a pleasing simplicity and solidarity of forms in his work. … He plans to concentrate on figure studies and prairie landscapes while he’s here.”

A few years later, after further raising his profile in Italy, Gordienko returned to Winnipeg to help care for his mother Vera, apparently for over a year and a half until she passed away, at age 86, in June 1982. Evidence that Gordienko remained active in art while caring for his mother came in the early spring of that year. As the arts section of the April 2, 1982, Winnipeg Free Press reported in a notice with the heading “Versatile artist,” Winnipeg’s Pembina Gallery was hosting an exhibit with “oils, pastels and woodcuts by George Gordienko.” There was no mention in the notice that Gordienko’s versatility had extended to pro wrestling.

Such was also the case in the Pembina Gallery’s brochure outlining its April 1982 exhibition of the works of artist George Gordienko. Referring obliquely to the early part of the career that had occupied nearly three decades of Gordienko’s life before he became a full-time artist, the Pembina brochure said, “His early working career took him extensively through numerous Canadian provinces. This gave him an encompassing insight and grasp of his own country while whetting his appetite to experience other lands and cultures.”

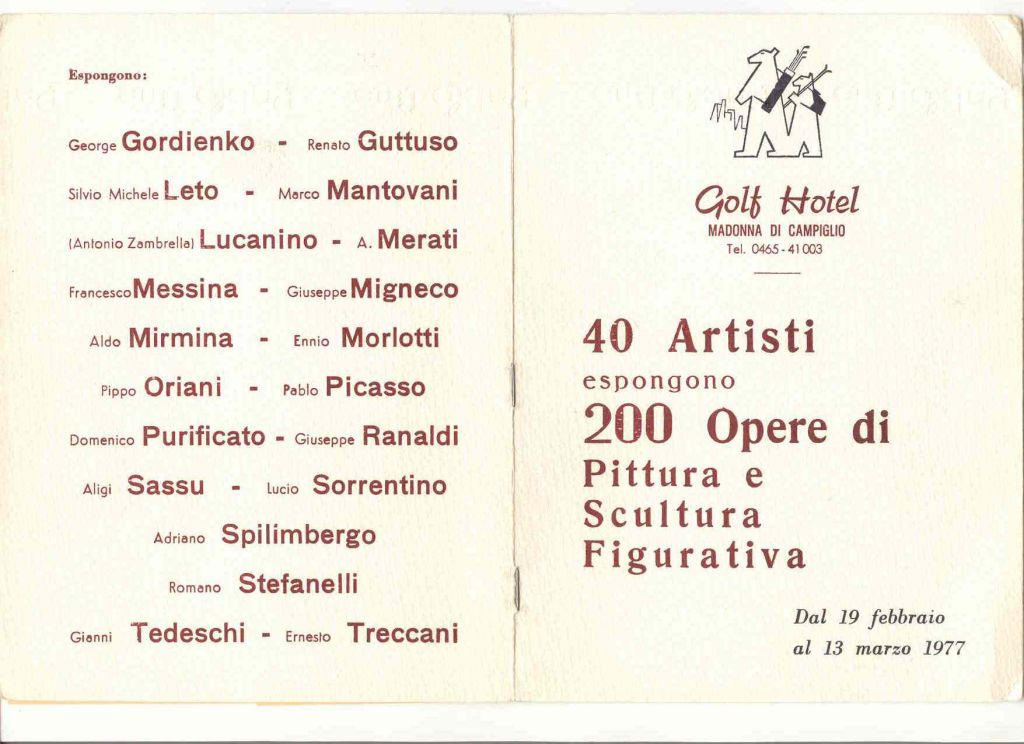

Even more obliquely, the brochure continued, “A successful business career allowed him to indulge this desire to the point where there are few countries that did not become a ‘port of call.’” The brochure made particular mention of Gordienko’s “15 year stay in London, England,” and the instruction he received at some of London’s leading art schools; the shifting of his European base from England to Italy, where Gordienko’s work had been displayed alongside works “by Miró, Calder, Moore, Ernst, Marini, Guttuso, and Picasso” and been “shown independently in Monza, bao Terme, Asiago, Sassuolo, Bologna, Madonna dia Campiglio and Sirmione”; and the inclusion or coverage of his work “in the Italian publications Arte, Scena Illustrata, Bollaffi National Catalogue of Modern Art, and Bollaffi National Catalogue of Sculpture.”

As quoted in the brochure, Gordienko commented, “Although my work is primarily figurative and realistic, I stress the … personality in each work.”

After returning to Italy, Gordienko settled back into a productive and fairly tranquil life, continuing to sell some paintings while taking time to experiment with his craft and—as he’d put it in his own words in the Pembina Gallery’s brochure for his exhibition in Winnipeg earlier in 1982—“attempt to exercise my own personality in each work.” There’s little doubt that he derived immense satisfaction from the fact that his second life—the life of a full-time artist—was now well established. The grind of wrestling and the burden of straddling two distinct paths were behind him—though Gordienko often said his path as a wrestler had led to his path as a serious artist—and he seemed full of appreciation for the artist’s path he was finally able to tread with both feet.

It appears that Gordienko spent part of 1983 in Spain studying Picasso, whom he’d met a couple of decades earlier, apparently during a wrestling tour of France, when the two got into a discussion on wrestling and art. Gordienko recognized Picasso as a brilliant artist who faced some criticism or scorn for his political views and his artwork when he was “on the way up” but who paid his dues and stuck to his guns until his perseverance paid off—all qualities Gordienko could definitely identify with. As numerous observers of Gordienko’s art would point out, especially in later years, Picasso’s influence on Gordienko extended beyond the inspirational, as frequent comparisons would be made between Gordienko’s later work and work Picasso produced during his surrealist period.

Determined to earn a reputation as a serious artist in his native country, Gordienko returned to Canada for good in late 1989 or early 1990. Settling on Vancouver Island, Gordienko set off in hot pursuit of “this great interest of his—surrealism,” according to Peter Redpath, who’d get to know Gordienko in his capacity as curator of Winchester Galleries in Victoria. In Redpath’s estimation, “From about 1990 until the end of his years on earth, he was able to explore [surrealism] with this intrigue—and he did so with much invention, much originality, [and] authenticity.” The eventual result, as Redpath sees it, is “a most original voice”—in a nutshell, exactly what Gordienko had set out to achieve when he left Italy.

After spending over a year in Victoria, Gordienko moved to a modest home up the island in the village of Black Creek, where he could live simply, keep distractions at bay, and simply paint—which he was known to do, nearly nonstop, for days on end. In his new home of Black Creek, Gordienko made every effort to minimize distractions from the outside world as he set about devoting his remaining years to painting, sculpting, and producing a body of bold, original work worthy of a serious Canadian artist.

A local artist who became a friend of Gordienko’s was Wayne Clarke, a fellow painter and sculptor who had a small gallery in Courtenay, about 13 miles down the coast from Black Creek. In 2005 Clarke told Ted Gordienko about the time George stopped by to introduce himself and show some of his work.

“I enjoyed the color, and I enjoyed the play of forms in his work,” Clarke told Ted. “I appreciated very much where his work had come from—the early moderns, especially Picasso, Miró, Braque, [and] numerous others. I was taken very much by that because all those people … were the basis for a lot of my art.”

Gordienko’s influences, in Clarke’s view, weren’t limited to fellow artists or masters but to people from all walks and all backgrounds. “All that he saw and experienced … is evident in his work,” said Clarke. “If you look at some of the drawings and paintings that he has done, you can see the very characteristics of the people in all the countries that he traveled to.”

Echoing many others who followed Gordienko’s growth as an artist after he settled in Black Creek, Clarke said Gordienko was far less an imitator than a seasoned artist who’d developed his own voice and his own approach to art.

“He had a great sense of humor, and I think that shows a great deal in his paintings. His witticisms and satirical pieces were very enlightening.”

Clarke continued, “He loved life. He loved to paint, and this showed in his work. He could smile at life. It was always playful—the characters in his paintings. … He poked fun at everything—at life, at politics, at religion, at specific people from time to time. One of my favorite pieces of his that I own is just a little painting about three inches square, and it says ‘Figure Bouncing on One Toe,’ and it just says, ‘I can dance like Nijinsky.’”

Just as impressive to Clarke as the distinct voice that was emerging in Gordienko’s work was the manner in which he went about that work. “He kept close to himself and liked to have a lot of time to himself … to do his work,” Clarke said. “I just watched the way he could pick it up and get right back into it after he’d let the colors set up for maybe a day or two or whatever. He knew right where he was going after something. He didn’t worry too much about it because if it didn’t work out, he could make the change quite rapidly and make it go somewhere else.” As for Gordienko’s technical skills, Clarke said, “He was very painterly in his approach to applying the paint, and that can be seen in some of his early work as well as his later work. He left nice lines, good brush strokes, [and] his color sense was wonderful. I appreciated the conditions and the way he can make the body work in whatever position he wanted it to be.

“His work is almost timeless because it isn’t dated.” Clarke said. Even though it’s derived from early moderns, he managed to create his own style and also his own integrity of composition, and, like I said, the color in that is very good.”

Aside from occasionally seeing fellow artists on Vancouver Island, Gordienko also took a little time from his rigorous regimen at home to get back to Victoria on occasion to see what was going on artistically in the city. One of Victoria’s leading galleries at the time, and ever since, was Winchester Galleries, purchased in 1994 by Gunter Heinrich, who played a major role in “[establishing] what soon became one of the premier commercial art galleries in Canada,” according to the Sept. 29, 2014, Victoria Times Colonist. When he took over the Winchester, Heinrich, as he told Ted Gordienko in 2004, was drawn to the Gordienko paintings already on display there.

“I was intrigued with the paintings,” Heinrich said. “I just thought they were fabulous—composition, great color. I mean, they were just interesting all around.”

Not long after Heinrich was settled in as owner and president of the Winchester, he got a visitor in the form of an ex-athlete who, though by then up around 300 pounds and limited in his mobility, could still cut an imposing figure. “George came in,” Heinrich told Ted Gordienko, “… and it was interesting because, you know, here’s this world champion wrestler you expect to be rough and tough. … George was gentle and, you know, a big guy, but he was very well spoken, very intelligent, and really understood art.”

Over time, Heinrich said, “we would have wonderful conversations about art and art history, and, of course, I got more and more intrigued about [his] work.”

Summarizing what he saw in Gordienko’s work, Heinrich said, “I think that George could pick up on things about human conditions—things that we all go through but don’t always talk about, and he was able to put a funny spin to it and just put some, you know, calligraphy into the painting or so and then … just nail it.” One result, Heinrich said, was that Gordienko’s work appealed to people of professional classes who wanted to invest in art that seemed to speak directly to them.

According to Heinrich, people who purchased Gordienko paintings—often in the $10,000–$20,000 range during the time the artist was based in Black Creek—generally did so for more than monetary reasons. “There’s a real sense of humor and also of joy that comes from [his] paintings,” Heinrich said. People come to [his] exhibitions and they feel good; they feel happy.”

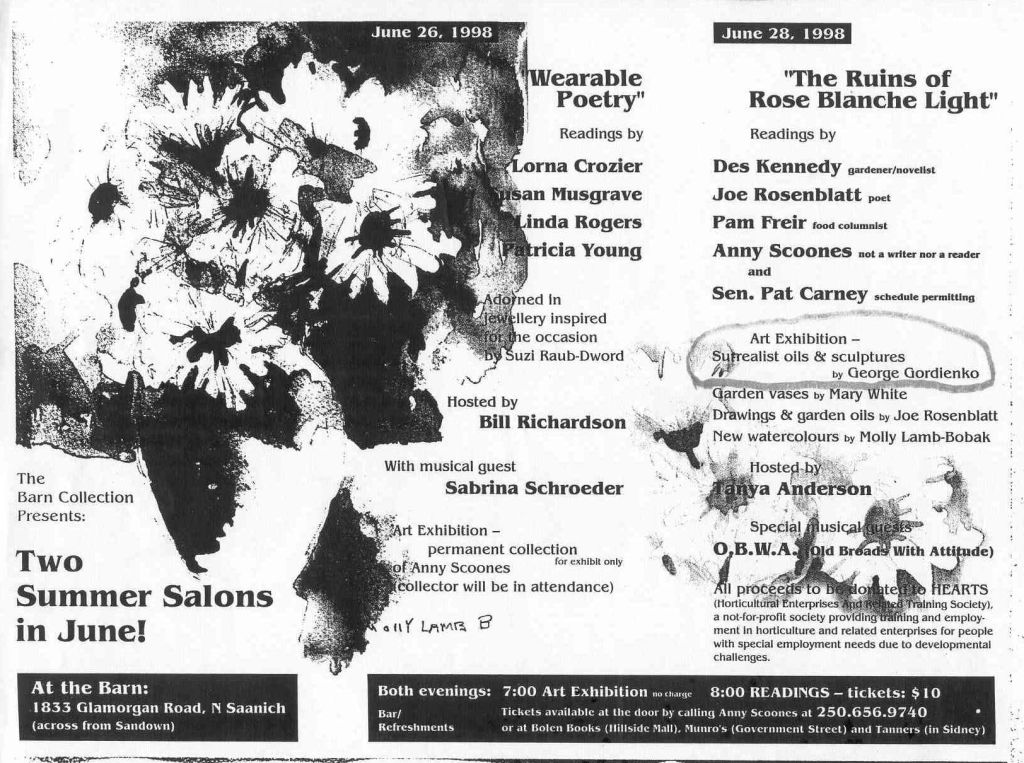

A brochure for an event exhibiting Gordienko’s work in 1998 (thanks to Ted Gordienko).

Gordienko’s work was exhibited a few times on Vancouver Island before he passed away in 2002, and it’s been exhibited on occasion since then. Part of the publicity for a 2010 Gordienko exhibit at the Winchester said, “George Gordienko was an artist and wrestler. Weighing about 260 pounds of solid muscle in his prime, he could, at the same time, create the most delicate and mysterious Surrealist paintings. How this Canadian wrestler became such a gentle and whimsical artist and person is a life-long adventure worthy of a creation by Ernest Hemingway.”

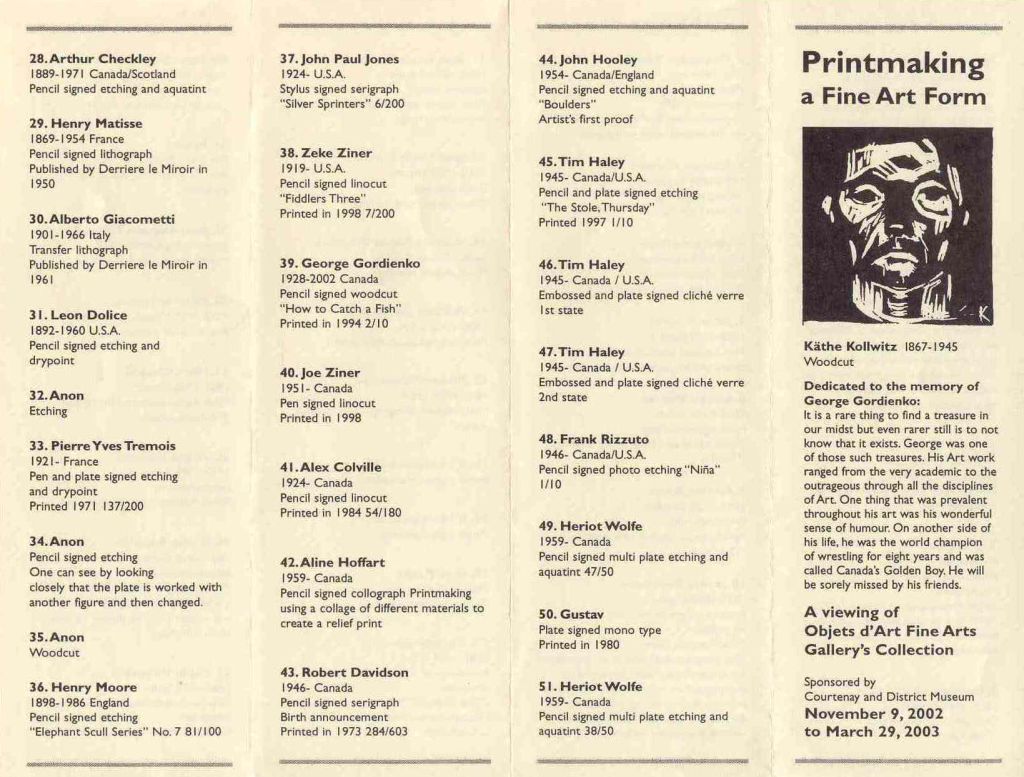

Brochure for an event exhibiting Gordienko’s work posthumously in 2002 (thanks to Ted Gordienko).

More recently, in January and February of 2020, shortly before the coronavirus shut things down for an extended time, the Winchester hosted an exhibition called “An Amusing Life,” which featured a collection of paintings by George Gordienko, many created during his years of relative isolation and frenetic productivity in Black Creek. Among featured paintings from Gordienko’s Black Creek period were colorful and expressive pieces with such titles as “Clown with a Long Nose,” “Deary You Make My Life Cheery,” “Tickle Me,” “Eroded Historical Monuments Mocking the Present,” and “A Man Who Licks His Own Boot.”

A look at those paintings (viewable in 2021 in full color at this URL) and at others created during the final decade of Gordienko’s life suggests, despite any difficulties related to aging or illness or the ramifications of his decision to leave Europe and to focus solely on his art, that the name of the exhibition was apt—that he’d been blessed, or rewarded, with a life that, on the whole, was amusing. Certainly, the artist recognized that he’d covered tremendous ground and had an important legacy to leave behind—a legacy that could conceivably earn him recognition one day as one of the most original and expressive Canadian artists of the second half of the twentieth century.

RELATED LINKS

- Dec. 20, 2022: George Gordienko finally has his day with great biography

- Apr. 28, 2022: BC police on hunt for stolen Gordienko art

- Jan. 17, 2022: Thesz wanted Gordienko, not Watson, to win NWA title in 1956

- Jan. 10, 2022: Gordienko: Canada’s top wrestler worldwide from the 1950s-1970s

- May 12, 2004: Nephew aims to boost Gordienko’s legacy

- The Artistic Canvas section

- Buy George Gordienko: Canadian Wrestler, Artist and Renaissance Man at Amazon.com or Amazon.ca