If you polled wrestling fans in Canada and asked who was the most successful Canadian wrestler worldwide during what was arguably professional wrestling’s peak period from the 1950s to the 1970s, you’d likely hear a lot of answers. Topping the list, perhaps, would be Gene Kiniski, who had an outstanding NWA world title reign from 1966–1969 and definitely made a big mark in Canada and abroad. Others might mention Canada’s other NWA world heavyweight champion, Whipper Billy Watson; Earl McCready or Yvon Robert, two Canadian legends whose outstanding careers were winding down in the 1950s; or Mad Dog Vachon, Killer Kowalski, Abdullah the Butcher, or Ivan Koloff, who were among top heels of the era. While it’s less than certain which wrestler Canadian fans would put at the top of the list of Canada’s top wrestlers worldwide during that period, one thing seems clear: George Gordienko would finish well down the list, if he made it on the list at all.

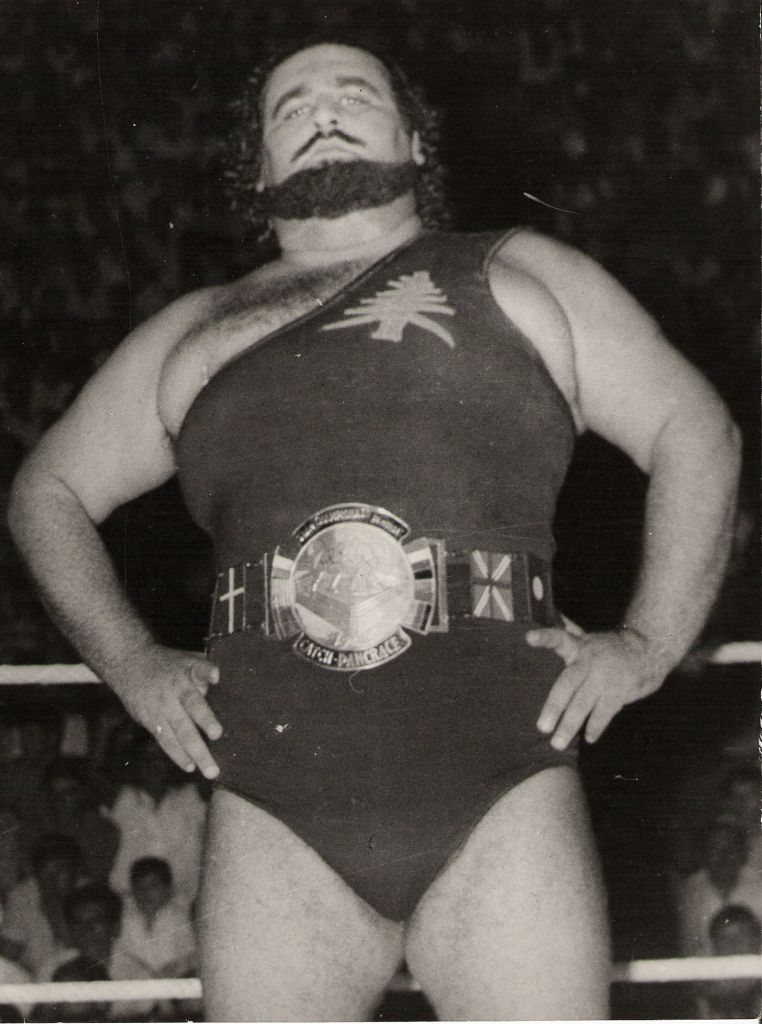

The oversight would seem reasonable, given that Gordienko—who held championships in British Columbia and the Prairies over the course of his long career—spent the vast majority of his wrestling career overseas. From 1957–1975 he was based primarily in the United Kingdom, where he held several championships and was widely considered one of the top professional wrestlers and shooters of his era, a consummate professional in the ring and in the gym, and one of the most respected wrestlers to travel the circuit for Joint Promotions, which at the time was one of the world’s busiest wrestling organizations.

But as successful and respected as he was in the United Kingdom, it was really through his travels away from his base in the UK that Gordienko made his strongest case for being considered the most successful Canadian wrestler worldwide during his years in the ring. During absences from the United Kingdom, Gordienko wrestled in a long list of countries that placed him among the top international wrestling attractions of his day. Among other countries where Gordienko wrestled in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, often in main events, were France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Spain, Lebanon, Iran, Libya, Nigeria, South Africa, Zambia, Australia, Trinidad and Tobago, Pakistan, Nepal, and Japan—and that’s not a complete list.

Gordienko’s reputation abroad was such that he was the wrestler of his era most often brought into a country—with the possible exception of his close friend Lou Thesz—to help establish a domestic wrestler as a national or world-class star or simply to help boost professional wrestling’s profile by filling stadiums for matches against domestic opponents who’d get a major rub from battling it out with the Winnipeg powerhouse. But while Gordienko was a proven attraction and main-eventer in many countries, it was especially his work in four countries that seems to cement his case for being considered the most successful Canadian wrestler worldwide during his era—and perhaps the most successful wrestler worldwide of any nationality from the 1950s–1970s.

GREECE

From 1963–1970 Gordienko participated in several spring and summer tours of Greece, a country that already had several decades of history as major center of professional wrestling. According to Bulgaria-based wrestling historian Phil Lions, the first major pro wrestling show in Greece, reportedly drawing between 40,000 and 50,000 people to a stadium in Athens, appears to have been a Dec. 2, 1928, event featuring Greek-born North American superstar Jim Londos in the main event. Major wrestling shows in Greece would follow in subsequent years, along with smaller shows held regularly in Athens and other cities around the country featuring local or regional wrestlers and typically drawing 1,000–2,000 fans.

Gordienko made his first visit to Greece in 1963 and was billed under a new surname, Korienko. Booked as powerful foreign heel, “Korienko” spent about a month facing a variety of opponents during Athens’ summer “catch festival.” His most notable opponents were Andreas Lambrakis, the top Greek wrestler of his era to fans in Greece; Spiros Arion, a young Greek who’d wrestled abroad but was just getting unveiled to fans in Greece in 1963; and George Bollas, a close friend of Gordienko’s whose ethnicity, grappling background, size, and masked persona (as the Zebra Kid) made him appealing to fans in Athens. Those four were the stars of the festival; and Gordienko, over the course of a month in Athens—which may have been interspersed with a few wrestling dates in smaller venues outside the city—definitely made a strong impression on thousands of fans who saw his battles with Lambrakis, Bollas, Arion, and other opponents in the 1963 Athens catch festival.

In May and June of 1965, Gordienko made the second tour of his career to Greece to participate in what was billed as the “Official World Catch Festival.” According to Lions, the abundance of stadium shows in Greece in May and June, along with other big shows peppered throughout the rest of the year, made 1965 “a big year in Greek pro wrestling [and] probably one of the most successful ones too” (see Lions’ excellent article, “The History of Greek Pro Wrestling,” at wrestlingclassics.com). Without a doubt, Gordienko, appearing again as Korienko, was a major part of that success; and according to records compiled by Lions, Gordienko drew multiple crowds of about 15,000 to Athens’ Apostolos Nikolaidis Stadium, which was a midsized soccer stadium of about that capacity.

In 1969 Gordienko returned to Greece for what, Lions says by phone, “was probably his biggest run.” That summer, three major competing groups ran series of successful stadium shows—totalling about 50 outdoor events—in Athens. The most prominent group was Harry Karpozolis’ promotion, which held another “World Catch Festival” from June to September, most of that time featuring George Gordienko—again, appearing in Greece with the surname Korienko—as the top foreigner.

As Lions reports in “The History of Greek Pro Wrestling”:

Initially the big superstar attraction on the catch festival shows was the returning George Gordienko. A lot of the shows were built around him defeating various Greek wrestlers until he finally met his match in the returning Spiros Arion. … Their rivalry culminated in the first ever cage match in Greek pro wrestling history.

The culmination of Gordienko’s success in Greece was his series of matches in 1970 against Atilio, one of many fierce opponents Gordienko considered a friend (thanks to Ted Gordienko).

While Gordienko was working for the Karpozolis promotion, opposition shows promoted by Theodoros Nikolarakos featured as the top heel a wrestler named Atilio, billed—falsely, according to Bulgaria-based Lions—as a Bulgarian. Atilio had wrestled in Athens for a few summers prior to 1969, and he, Gordienko, and George Bollas were probably positioned as the top foreigners who wrestled in Greece in the 1960s. But while Gordienko and Bollas had faced off in several high-profile matches during that decade, the 1960s came to a close without Gordienko and Atilio working for the same promotion and having any opportunity to face off. That changed in 1970, when Gordienko and Atilio both worked for the Karpozilos promotion.

Lions reports, in “The History of Greek Pro Wrestling”:

The major feud from July 1 through early August was Atilio vs. Gordienko. They wrestled each other in a couple of tag team matches and several times in singles bouts. Atilio won their first singles match via disqualification. The angle in the second match was that Gordienko beat him up so bad that Atilio had to be taken to the hospital. Gordienko won the third match as well. Then came time for the big blow off match, which was on July 26th. It was a cage match, the second cage match in Athens history ([the] first one being Gordienko vs. Arion the year prior). In the cage Atilio finally managed to defeat Gordienko.

Summing up Gordienko’s contribution to professional wrestling in Greece, Lions writes, “I would definitely put him up there with Atilio as the top foreign star in the history of Athens. They both made several trips to Greece, always worked on top and drew some big crowds.”

NEW ZEALAND

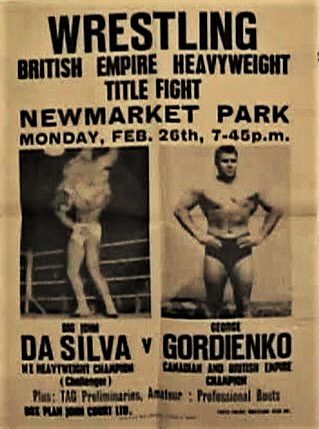

One of the best examples of Gordienko answering the call to help establish a national wrestling hero came in 1968, when, billed as the British Commonwealth Heavyweight champion, he geared up to defend that title in New Zealand against John da Silva. While most of da Silva’s work as a wrestler since he’d turned pro in 1958 had been overseas, primarily in Europe but also in North America and Australia, it appears da Silva had been recognized as the New Zealand Heavyweight champion for about half a year prior to facing Gordienko at Newmarket Park Stadium in Auckland on Feb. 26, 1968. That match, which drew about 10,000 fans to the midsized stadium, appears to have ended without a conclusive finish.

A poster touting one of the matches that would help establish John da Silva as a bona fide hero to New Zealanders (thanks to Ted Gordienko).

In the return match three weeks later, before a packed crowd at Auckland’s indoor YMCA Stadium on March 18, 1968, da Silva captured the British Commonwealth Heavyweight championship from Gordienko after a highly heated battle. For the next eight years da Silva would trade the British Commonwealth title with major wrestlers coming to New Zealand from overseas, and he continued to hold the New Zealand Heavyweight title—which wasn’t on the line during his Auckland matches against Gordienko—for about another decade after winning the British Commonwealth championship.

While da Silva was a successful and respected wrestler in the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, India, and elsewhere, he was positioned at an altogether different level in New Zealand, based in large part on the amateur credentials he’d established in New Zealand and overseas in the 1950s. For a solid decade from 1967-1977, da Silva combined moderately successful travels to Europe and Asia with wildly successful spells wrestling around New Zealand, where he faced off against highly regarded foreign competitors brought in to establish his credentials to the New Zealand audience as a grappler who was second to none. As far as Gordienko was concerned, New Zealand wrestling historian Dave Cameron—who lived in Britain for several years in the 1950s and 1960s and rates Gordienko as “one of the very best wrestlers I ever saw”—says, “[John] always told me he was going to bring George out here [to New Zealand].” In 1968 da Silva got his wish as he hosted Gordienko, both as a wrestling promoter and as a friend who opened his home to Gordienko for several weeks as the two tore things up in a series of outstanding matches that established da Silva to New Zealand fans as arguably the best wrestler in the world and set the tone for a successful era of wrestling in New Zealand.

As da Silva put it in an Auckland newspaper—possibly the New Zealand Herald—the day after capturing the Commonwealth title from Gordienko, “If I had lost, I intended to go back to [Europe]. Now—except for an occasional overseas trip—I will stay here.

“New Zealand will now see world class wrestlers. They will have to come here for my Empire title.”

Da Silva’s prediction came to fruition as he proved himself a worthy champion and representative of his nation against the best from the outside world, and for years afterward he made good on his promise to attract, and turn back, world-class challengers from around the globe. But among the top wrestlers he ever faced, da Silva, at kiwiprowrestling.com, rated Gordienko as the toughest. On top of that, Cameron reports that, many years after the 1968 Gordienko-da Silva series in New Zealand, “[John] told me George was his greatest friend in wrestling.”

IRAQ

Arguably the highlight of George Gordienko’s wrestling career was a visit he made to Iraq in late 1970. The instigator of Gordienko’s Iraqi tour was Adnan Al-Kaissey, well-known to North American fans of the recent era as an Iraqi heel in the 1980 and 1990s—most famously, as Saddam Hussein sympathizer General Adnan.

Although Adnan’s real-life views at the time weren’t at all what was portrayed by the then-World Wrestling Federation, Adnan actually had a real-life connection to Saddam Hussein. According to Mike Mooneyham, Adnan attended the same school as Saddam Hussein, who was two years his senior and “a boyhood acquaintance of [Al-Kaissey].” According to the book Weird Minnesota: Your Travel Guide to Minnesota’s Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets, Al-Kaissey, who’s spent much of his adult life living in Minnesota, “played backgammon with Saddam Hussein in a Baghdad café” (all Weird Minnesota quotes are from p. 117). Mooneyham writes, “The two played sports together, matched skills at dominoes in open-air coffee shops, and dined on their favorite meal of shish kebob.”

Adnan was a gifted athlete and amateur wrestler who left Iraq for the United States in the late 1950s. After two years as an All-American wrestler at Oklahoma State University, he left the university to get into professional wrestling and won numerous titles during the 1960s as Native American character Billy White Wolf.

After wrestling in Japan, Australia, Hawaii, and the Pacific Northwest during the first 11 months of 1969, Al-Kaissey made a visit to Iraq. By that time, his old acquaintance Saddam Hussein had risen to the position of deputy minister, and after Al-Kaissey arrived back in Iraq near the end of 1969, he says in Weird Minnesota, “Saddam saw me on TV and sent for me. He told me, ‘This is your country, and you’re not going to leave now.’ If he wants you to do it, you do it, because he has a lot of hit men.” According to Adnan, Saddam wanted to keep him in Iraq because he saw professional wrestling as a potential tool to help consolidate his power in Iraq—or, as Weird Minnesota puts it, “Hussein decided that wrestling matches were the perfect diversion from his many executions.”

Weird Minnesota reports, “[Al-Kaissey] became Hussein’s director of youth activities and promoted his sport across the country.” A major step toward doing so involved setting up a major wrestling show—due to take place in a stadium in Baghdad; and Al-Kaissey decided the perfect opponent for him to face would be George Gordienko.

As Adnan wrote in a letter to George’s nephew Ted Gordienko in 2006, “I met George in London and we became very good friends. We [wrestled] together in England for about one year.”

In a 2005 interview, Al-Kaissey, discussing the promotion of his Nov. 6, 1970, match with Gordienko at Al-Shaab Stadium, told Ted Gordienko he was out promoting the match “for about six [or] seven months, day and night.” In a 57Talk interview with Gary Cubeta, Al-Kaissey said, “I walked around for about six months. … I toured the whole country, talking about it [in] high schools, elementary schools, college, universities, [and to] union people—everything.”

“I got George Gordienko pictures all over the country,” he told Ted Gordienko.

In the Cubeta interview, Al-Kaissey said, “When we had the show with George Gordienko … I kid you not, the whole city of Baghdad was like a ghost [town. There was] nobody in the city. They [were all] at the stadium.”

In various interviews Al-Kaissey estimated the stadium attendance for his match with Gordienko at between 150,000 and 200,000 people, with approximately the same number outside the stadium. “Me and George, we [drew] over 300,000 or 400,000 people,” Al-Kaissey told Ted Gordienko.

As for the event, it was a one-match show, with Gordienko, apparently billed again as the British Commonwealth champion, set to engage in a 60-minute, best-of-three-falls match, apparently divided into three 20-minute periods. The start of the match was delayed, Al-Kaissey told Ted Gordienko, when Saddam Hussein phoned Al-Kaissey in the dressing room and asked him to delay the start of the match for a few minutes until Saddam could get from his palace to the stadium. After waiting for Saddam to arrive, Al-Kaissey said, “I got the message that he could not get into the ringside [area] with the dignitaries” because the crowd on the field was so thick. “He had to stand up in the general admission [area],” where, Al-Kaissey said, “he could not see the match.”

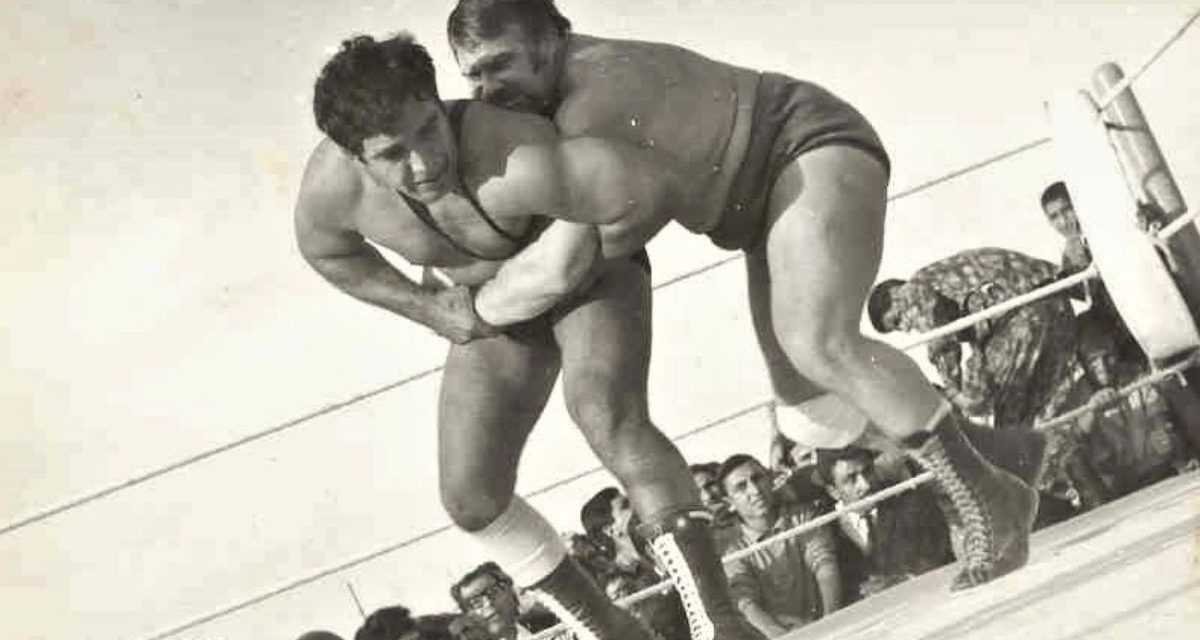

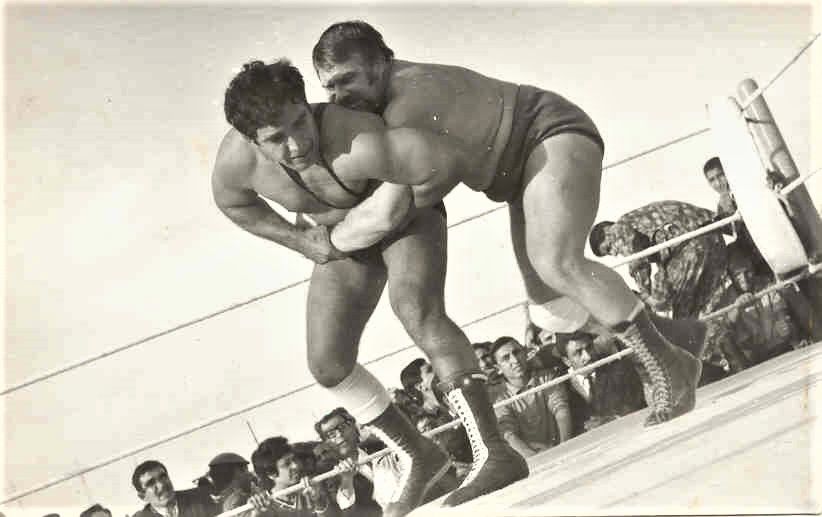

Adnan Al-Kaissey and Gordienko square off in Baghdad, November 1970 (thanks to Ted Gordienko).

Weird Minnesota reports, “The ring was surrounded by guards armed with submachine guns. Gordienko looked around nervously and told [Al-Kaissey] to be careful not to hurt himself for fear of retaliation from the crowd and the soldiers. Guess who won that match.”

The original plan was for Al-Kaissey to win two of three falls, but Ted Gordienko reports things were so heated in the stadium that George called an audible after Adnan took the first fall as planned, by disqualification. As Al-Kaissey reported to Ted, George Gordienko insisted, “You’d better beat me two straight because if you don’t I’ll be dead.” Adnan went along, winning the second fall to end the match after about 40 minutes. After the match, shots were fired into the air in celebration, and fans rushed the ring. According to Adnan’s account in his letter to Ted, “Three people died. They were [stomped] on and died. I had to go to their families and meet with them.”

“I have no idea how [George] got out of the ring,” Al-Kaissey told Ted, describing his opponent’s escape as “a miracle” and adding that, immediately after the match, Saddam ordered the two wrestlers to head straight to a television studio. In the aftermath of the match, Adnan reported, Gordienko continued to get VIP treatment in Iraq. As Adnan wrote in his letter to Ted, “George was loved by the people. They [visited] him at the hotel. They gave him presents—gold chains, watches and more.” Adnan, meanwhile, remained in Iraq for a few more years—he says through no choice of his own—before resuming his wrestling career in North America, where he achieved considerable notoriety and fame, though it probably paled in comparison to what he orchestrated in 1970 with the assistance of George Gordienko.

INDIA

Almost on a similar scale to his presence and impact in Iraq were Gordienko’s tours in India during the middle part of his career and then toward the end of it. In the early 1960s Gordienko spent an extended period in India, where huge crowds were often reported in cities such as Bombay, New Delhi, and Kolkata. As the British magazine The Wrestler reported following a five-month India tour by Gordienko, “Only recently Gordienko returned to England from a very successful tour of India, where some of the biggest audiences—sometimes amounting to 60,000 people—watched the capable manner in which Gordienko handled himself against the top-notchers of Indian wrestling—men who are almost legendary figures in the Far East.”

It’s unclear whether Gordienko faced Indian legend Dara Singh during his 1960–1961 tour of India, though it seems inconceivable that the two wouldn’t have met in some high-profile matches at that time. Some of Gordienko’s travels in later years are hard to trace or confirm, but documented beyond any doubt is a hugely popular pair of matches he had back in India in 1975, as his wrestling career was drawing to a close.

Although Gordienko seemed inclined to call it a career following a serious ankle injury he suffered in the ring in Germany in 1974, he worked himself back into wrestling shape and agreed to wrestle on at least two major stadium shows in India in March 1975, when he was 47 years old—one of them against his good friend and bitter ring rival Dara Singh.

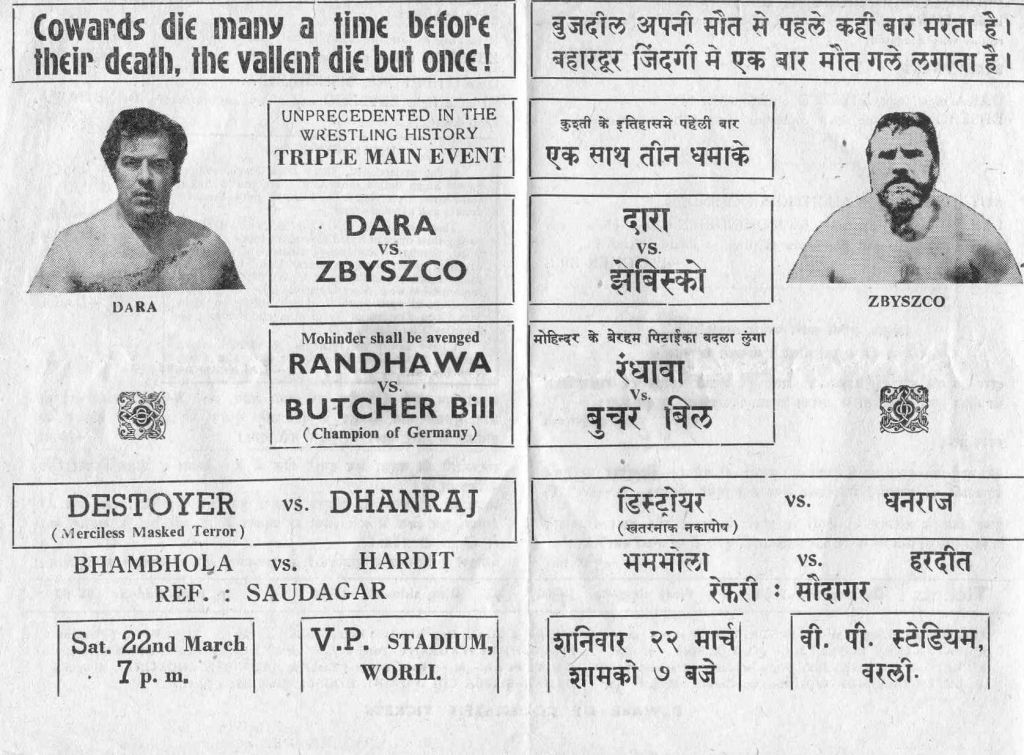

Before getting to Singh, however, Gordienko—billed in India as Firpo Zbyszco—had to face Dara’s younger brother Randhawa on a March 1 show at Mumbai’s Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium. For over three decades from the 1950s–1980s Randhawa was an extremely popular wrestler in India—at times billed as the Indian champion—who, like his older brother, got into movies, though he was nowhere near the level of star, in or out of the ring, that Dara was. A newspaper ad touting the match, held in a stadium likely accommodating over 50,000 fans for wrestling, featured a single photo—that of a hulking, imposing-looking forty-something version of George “Firpo Zbyszco” Gordienko set for battle, with a caption or heading to the side: “Randhwa’s Life in Danger.”

Fortunately, Randhwa survived the match, though he lost his battle with “Zbyszco.” Coming out of the match was an announcement that the main event on the next big show three weeks later would be a meeting between Dara Singh and the dreaded Firpo Zbyszco.

George “Firpo Zbyszco” Gordienko’s March 1975 showdown with Dara Singh in Mumbai, India, was intended to be the final match of Gordienko’s wrestling career. Their meeting was so successful, however, that they had another showdown in Southern Africa five months later to close out Gordienko’s career (thanks to Ted Gordienko).

This time it was Dara’s life that was deemed to be in danger, and as an apparent precondition to his Mar. 22 match in Mumbai against Firpo Zbyszco, Dara Singh publicly signed and released a statement indemnifying the wrestling promotion in Mumbai “from all responsibility whatsoever as regards injury of any sort, crippling, or even death to myself, during my fight with Firpo Zbyszco at V.P. Stadium, Bombay [Mumbai], on Saturday 22nd March, 1975.”

Gordienko/Zbyszco’s March 22, 1975, battle with Dara Singh, reportedly, was as brutal as expected, and the end of the match apparently came after Gordienko launched himself from a corner post or turnbuckle and put his knee right through the ring boards when Singh rolled out of the way just in time. Apparently on the heels—and as a result—of the resounding success of his 1975 program in India against national icon Dara Singh, Gordienko/Zbyszco was invited to reprise his mortal feud with Singh later that year in Zambia, a nation in which an Indian minority had a significant stake in the national economy. That encounter, in August 1975, about five months after their pairing in Mumbai, would be the final match of Gordienko’s wrestling career.

* * *

And what a career it was—one that makes a compelling argument that Gordienko was Canada’s top wrestler worldwide from the 1950s to the 1970s … and one that strongly suggests he’s deserving of a serious look back by North American fans in the current era at a wrestling great whose legacy shouldn’t be overlooked any longer.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Watch for more from Steve Verrier previewing his George Gordienko biography in the coming weeks. Steve Verrier has also contributed in the past to SlamWrestling.net.

RELATED LINKS

- Dec. 20, 2022: George Gordienko finally has his day with great biography

- Apr. 28, 2022: BC police on hunt for stolen Gordienko art

- Apr. 25, 2022: Gordienko was destined to be an artist

- Jan. 17, 2022: Thesz wanted Gordienko, not Watson, to win NWA title in 1956

- May 12, 2004: Nephew aims to boost Gordienko’s legacy

- Buy George Gordienko: Canadian Wrestler, Artist and Renaissance Man at Amazon.com or Amazon.ca