Part 1 of 4

- Part 1: Seelie Samara a forgotten African-American great

- Part 2: Seelie Samara a star around the world

- Part 3: The final years and legacy of Seelie Samara

- Part 4: Big George: The origins of Seelie Samara

On March 13, 1938, Steve “Crusher” Casey stepped into the Boston Garden ring to defend his newly won American Wrestling Association (AWA) title against a local contender. Having ended a brief spell of uncertainty around the title — one of several of wrestling’s “World Heavyweight Championships” — Casey now sought to silence the critics that believed another man was the true champion of the city.

Opposing Casey that night was someone who was a relative unknown just a few months earlier. A former boxer-turned-carnival strongman, that man, George Hardison, was now the star of the local promotions of Charley Gordon under a new moniker — that of a powerful, gutsy, and furious-yet-friendly foreign champion — Seelie Samara, champion of Ethiopia and himself a claimant to the World Heavyweight Championship.

In reality, Hardison was a Georgia-born kid who sought fame in the boxing ring but found it in wrestling rings across North America — and the world. Newspapers at the time heralded Hardison’s match against Casey as an important milestone — “the first Negro man to challenge for the World Heavyweight Championship.”

But Hardison (or, more correctly, Samara) deserves a much bigger place in history — as a star, a grappler, a man, and as the first true “Black World Heavyweight Champion” of professional wrestling.

This is the first part of the remarkable story of George Hardison, Seelie Samara, and one of the most influential wrestlers you’ve never heard of — until now.

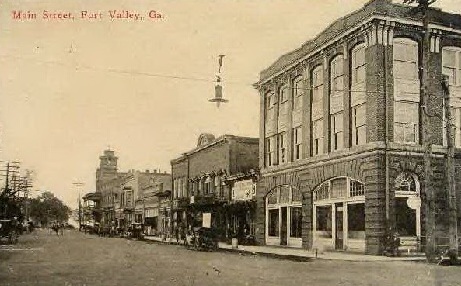

Main Street, looking east. Fort Valley, Georgia, circa 1910.

Early Life

Like many born at the turn of the 20th century, pinpointing the exact birthdate of George Hardison is tricky, as there are two commonly cited dates: December 28, 1905, and July 8, 1906. The second date, however, is the one used by surviving family, so it is the date most likely to be accurate.

Regardless of the day, month, or year, we can confidently say that George Hardison was born in Fort Valley, Georgia, to Alfred and Mathilda Hardison (née Riggins). George was the third child to Alfred and Mathilda, with his older brother, John, born around 1895, and an older sister, Mable, born around 1876.

Little is known of the early life of George, except that he attended the local school and could read and write. What is known, however, is that by 1920 the Hardison family was living in a house on Pine Street, with brother John and his wife, Fannie, the heads of the household. 1

Other residents of the Pine St. household included George, their mother Mathilda (now styled “Mattie” and sadly, a widow), Mable (now surnamed Edwards, also widowed), and her children, Pauline (age six) and Willie (age three). According to census records, both George and Joe were laborers at the local crate factory, while Mabel worked as a cook for a private family in the area.

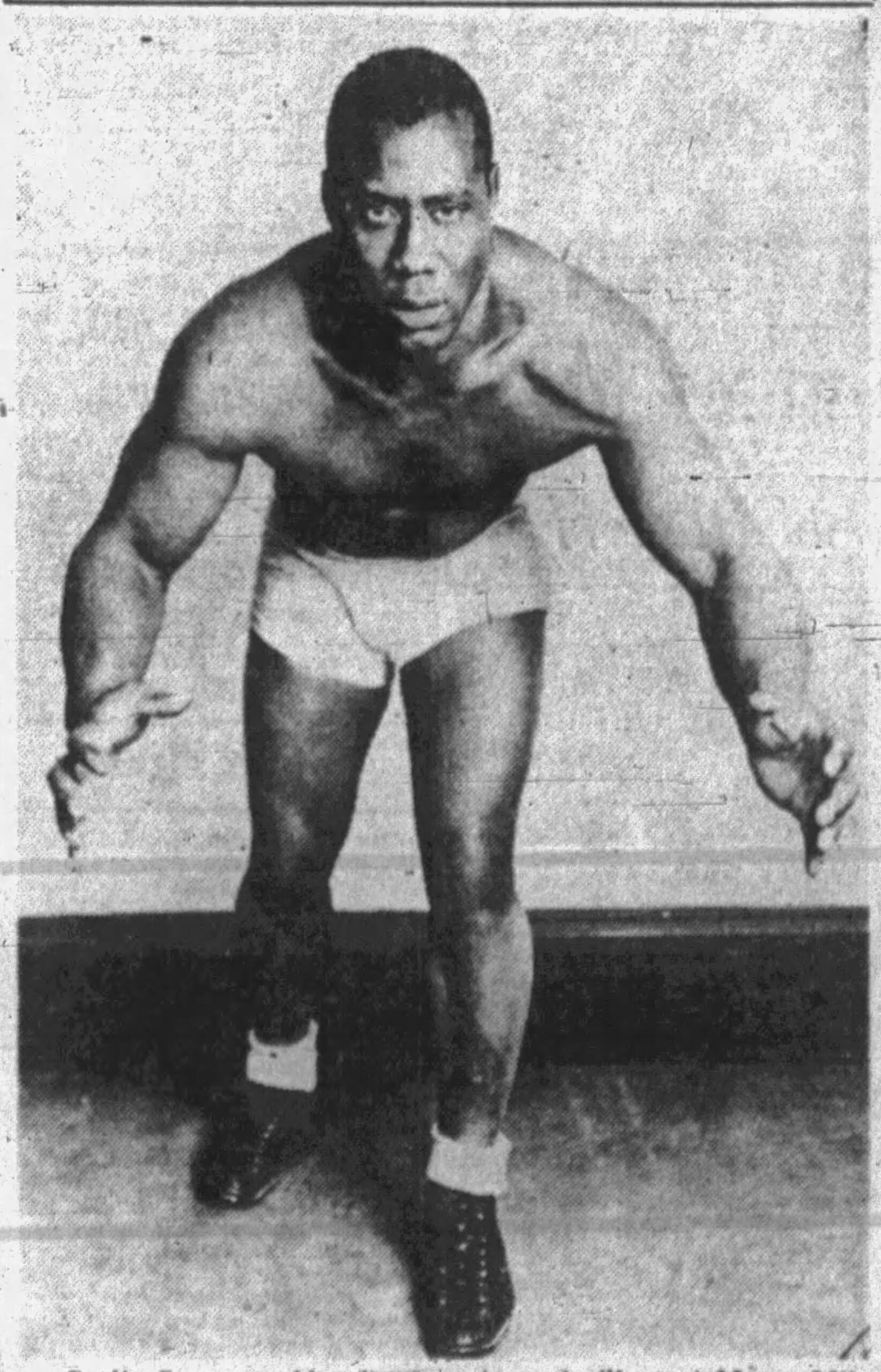

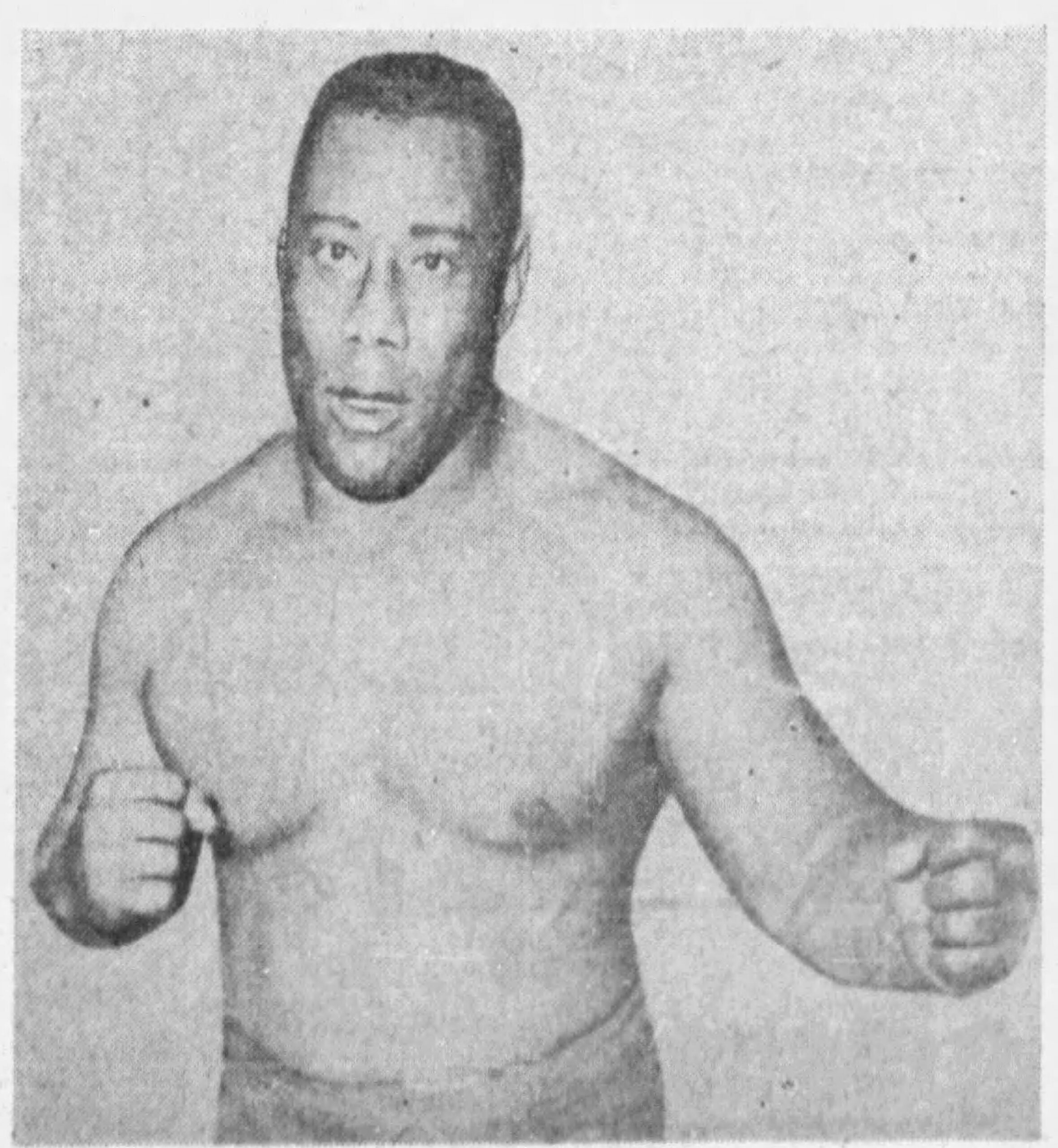

Seelie Samara circa 1938.

Protégé and Pugilist

If the early years of George Hardison provide sparse details, the start of his sports career is the subject of almost complete mystery, beyond the knowledge that he tried his hand as a boxer.

Hardison was a sturdy-built man if there ever was one. He stood 5-foot-11, and weighed 220 pounds in his early career but rose to as much as 265 pounds later on. He was trained by a welterweight boxer named Joe Walcott.

No, not that Joe Walcott. George Hardison’s mentor was “Barbados” Joe Walcott, and the better-known “Jersey” Joe Walcott of the 1930s was actually named Alfred Cream, and adopted the new name in tribute to his idol.

Also known as “the Black Demon,” Barbados Walcott was a formidable fighter who won most of his bouts by knockout. Once having held a claim to the welterweight boxing championship of the world, by his later life, Walcott was facing hard times, having squandered his fortune many times over.

To make money, he worked various trades, including as a stoker 2 , a custodian at Madison Square Garden, and a trainer of prospective boxers, with the young Hardison one such taker. Some sources claim Hardison’s father, Alfred, had a pre-existing relationship with Walcott, leading to the pairing, but this is speculation.

Just when (and where) Hardison trained to fight is, again, a mystery, though it is known that Barbados Walcott spent much of his later life in Pennsylvania and New York. Because of this, there is great difficulty in determining which boxer was Hardison.

The difficulty arises for a couple of reasons. First was the naming conventions used by fighters of the era. Like professional wrestlers, boxers often used ring names to help set them apart from the crowd. One such naming convention was to use the last name of your trainer, with “Young” affixed at the front — a fitting name for a prized protégé.

The only problem was that Joe Walcott taught many fighters, meaning there were many “Young Walcotts” — problem number two. Because of this, differentiating one pugilist from the next can be challenging, if not impossible. Despite that, however, there are some hints.

A likely “contender” for the true identity of George Hardison is a “Young Walcott” of Washington, Pennsylvania, who, at 220 pounds, was billed by the Pittsburgh Press in August 1929 as a “knockout sensation!” However, this identification is uncertain, as Hardison is definitively located in Massachusetts two years later. Still, it remains possible.

Another potential ring name came from Spokane, Washington’s Daily Chronicle, which stated in May 1946 that he “used to box under the name of Young Woldgast (sic).” However, there is no corroborative evidence for this claim outside the article.

Hardison’s life got a little more crowded when he married Mary Louise Andrews on May 26, 1931, in Charlemont, Massachusetts. 3 The marriage was well-timed, as their first child, Douglas, was born just over a week later, on June 8, 1931. Mary had had a rough year, with her mother dying the previous summer, so the double blessing of a child and a husband likely provided joy and excitement in equal measures.

The marriage of Mary and George would prove successful, producing six children: three sons, Douglas, John, and George Jr., and three daughters, including Janice Lee and Lois. 4 The family home in Greenfield, Massachusetts, would be Hardison’s base for at least the next nine years.

“Tiger Man” John Pesek trained George Hardison for the ring. Few wrestlers have as fearsome a reputation as Pesek, past or present.

Carnival Strongman Turned Tiger Man Trainee

Now with a family to feed, Hardison gave up his pugilistic pretensions, ditching the chance of boxing for the steady hustle of the carnival. While carnival life took him from his family, the young father could provide for his young family by performing as a strongman on the carnival circuit.

According to the Harrisburg Evening News on January 13, 1939, while crossing the country with a travelling circus, the legendary “Nebraska Tiger Man” John Pesek “marvelled” at the young Hardison performing a feat of strength and realized he was an ideal pupil. Pesek was one of the most feared shooters (highly trained and potentially dangerous) wrestlers in the sport and knew that George’s strength and his “thousand holds” would make him a formidable force in the ring.

The article places Pesek’s discovery and subsequent training of Hardison as taking place three years earlier, in 1936. How long the training lasted and where Hardison made his debut are unknown — as is the transition to “Seelie Samara.”

The Evening News article provides a contrasting backstory for Hardison. “Samara turned rassler 11 years ago after boxing 5 or 6 years before that as a pro,” sports writer Charles Washington explained. “He changed over because he had gotten too many raw ends of the deals and thought that maybe rassling would be better.”

While the Evening News article provides an impressive wealth of information, the 1930 start date for Hardison’s career simply does not make sense. After all, his own trainer, John Pesek, stated he discovered Hardison with the carnival around 1936. That said, he may have attempted a brief grappling career under the Young Wolcott name before turning to the carnival after minimal success.

Regardless of the article’s accuracy, it provides some insight, from Hardison himself, into his meteoric rise in the wrestling business. The same article states that “Ras (Ras Samara, another variant of the Samara ring name used by George Hardison) believes ‘Negroes chances are good in rassling if he has the guts and is unafraid.’”

As a student of Pesek, this was certainly the case with Hardison. Just when that jump from George Hardison to Seelie Samara occurred is unknown. What is known, however, is that it was likely Pesek, through a connection with either Al Haft, who was Columbus, Ohio’s wrestling kingpin or Jack Pfefer, New York mat impresario, that Hardison gained his initial bookings with Charley Gordon, a secondary Boston promoter.

A Star in Boston

Charley Gordon was himself a former boxer, having gained considerable success in New York rings the previous decade. Now promoting in Massachusetts, Gordon had a steady circuit of 14 clubs throughout the Greater Boston area, including stops in New Bedford, Brockton, Salem, Quincy, Natick, Hyannis, and Boston proper. 5 His main venue, the Boston Arena, regularly attracted thousands of spectators. Still, overall, Gordon lagged considerably behind the promotional powers of Gordon’s rival and the promoter of the Boston Garden: Paul Bowser.

Bowser and Gordon were locked in a promotional war since the start of the 1930s, with Bowser always holding the upper hand, thanks to his control of the Garden — with a capacity triple that of Gordon’s home base, the modest, 5,000-seat Arena. To better compete with the dominant Bowser, Gordon joined forces with Pfefer in 1934.

Pfefer and Bowser were former partners, and the latter was a principal of wrestling’s “Trust” designed to tackle the promotional competition that was Jim Londos. However, Pfefer was never complacent — always on edge for real (or, often perceived) threats to his business — and schemed himself into an agreement with Londos to seize all of wrestling as their own.

The scheme, however, turned out to be a trap, with the erstwhile and diminutive Pfefer unsuspectingly double-crossed while out of the country. The result was a new “Trust” comprising the greatest names in the sports, including Jack Curley, Paul Bowser, and Tom Packs. Combining forces with Londos and his allies, the new Trust was the most powerful force wrestling had ever seen. 6

Pfefer, left on the outs with sometimes partner Rudy Miller and the Johnstone brothers, wanted blood and sought alliances anywhere he could to do damage to his enemies.

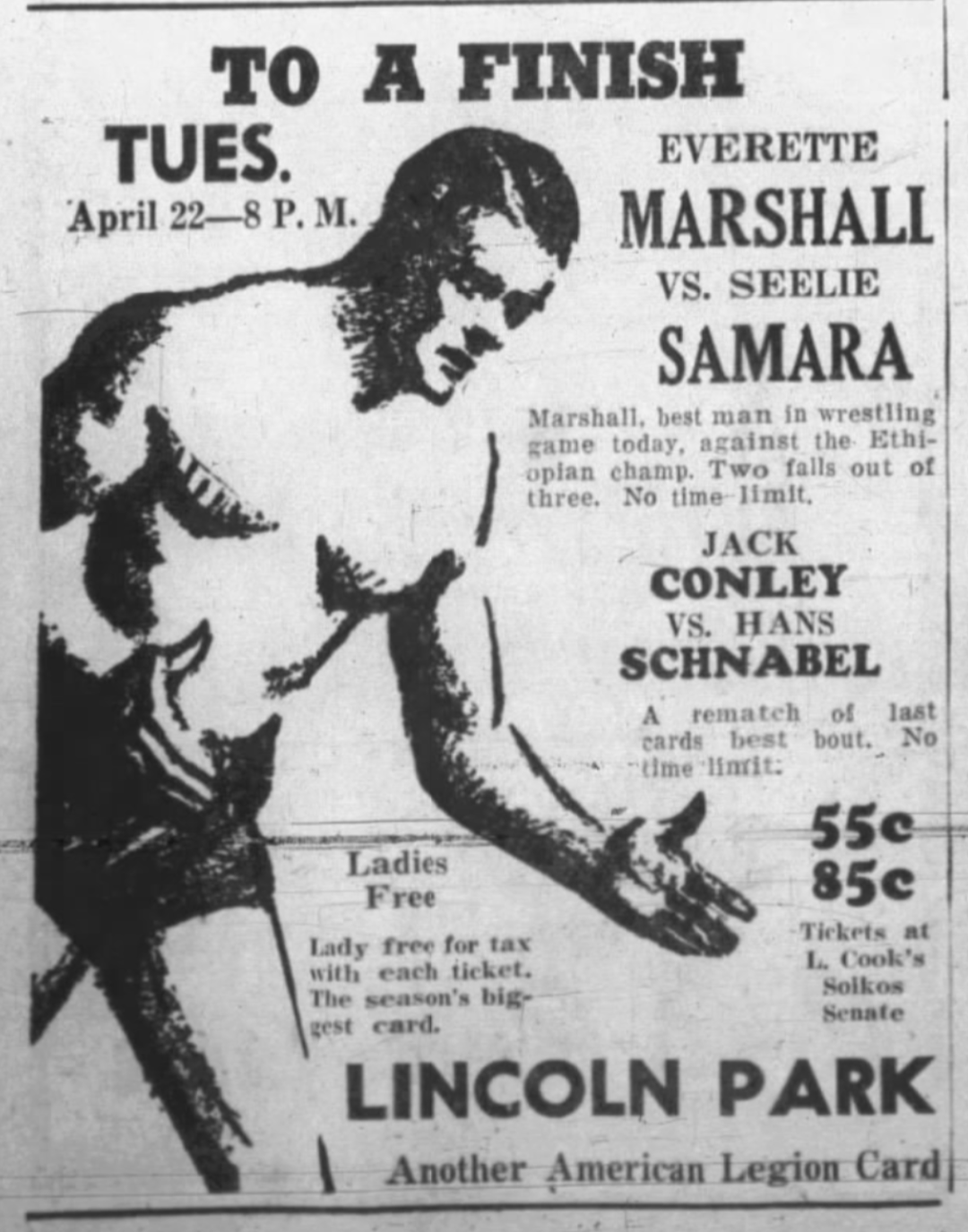

Gordon found a strong ally in Pfefer and used several of his talents in his promotions, including Hans Schnabel, Lee Wang Chong (Chicago-born Chinese wrestler Arthur Henry Wong Dock), Charles “Midget” Fisher, comedic-villain Count Von Zuppe, and another African-American boxer-turned grappler — Tiger “Flowers” Johnstone.

Hardison next appears in the records as “Seelie Samara,” defeating Ed McNeil in 15:48 on December 7, 1937. He followed up his impressive first victory with another over McNeil, taking two straight falls in just 25 minutes in Quincy on November 23. 7 In many of his early matches, Samara used his favorite hold — the “flying horse.”

The origins of the “Seelie Samara” name are something of a mystery. Still, the character is clearly based upon the figure of Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia and a figure of constant fascination during the time period. To add provenance, the backstory was created explaining that Samara was a close friend of the emperor and was Ethiopia’s national champion.

Samara’s rise to prominence continued, with quick victories against Pat Schaeffer, Henry Wycoff, Jesse James, and other names in the coming weeks. In December 1937, the Boston Globe called Hardison the “Sable Sampson” and claimed he was “the strongest negro in the world.”

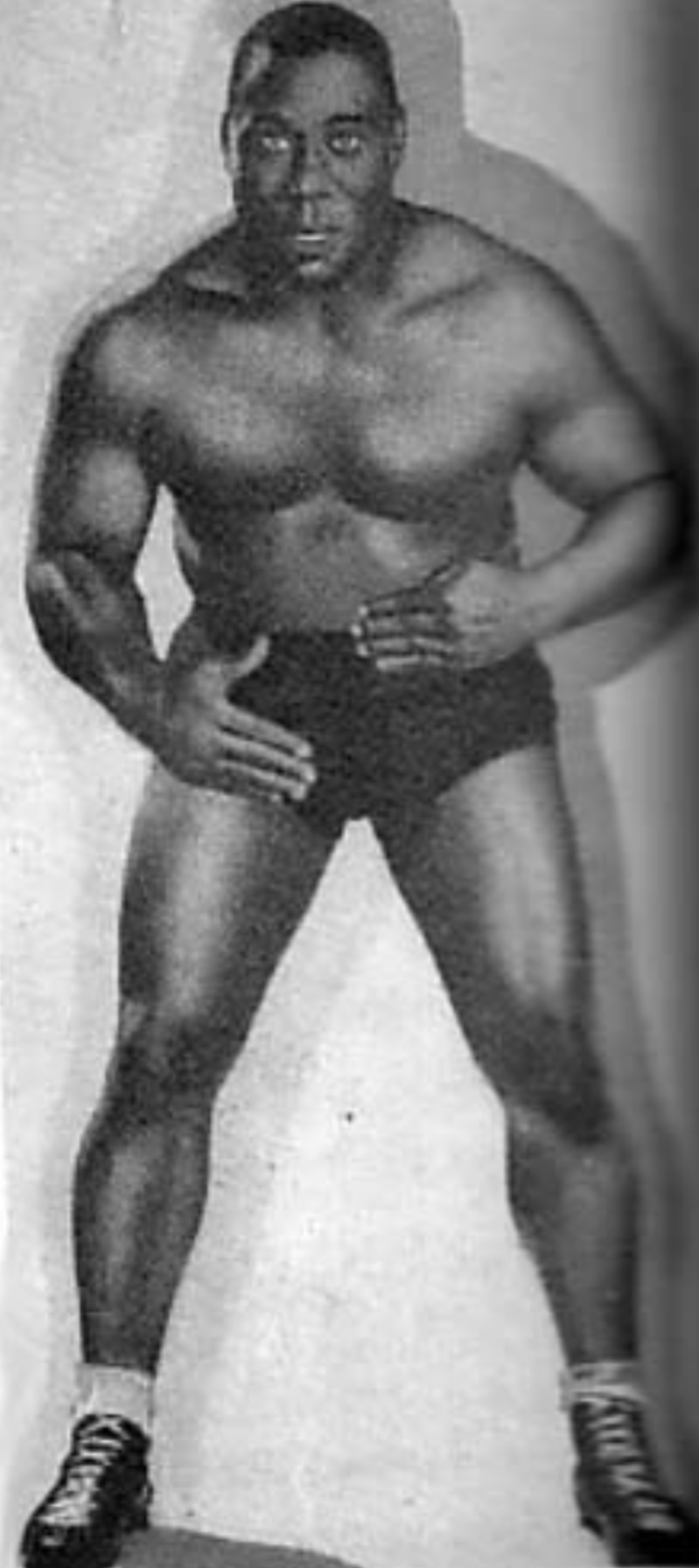

Seelie Samara, circa 1945.

Heavyweight Champion (of the World?)

It was around this time that Seelie Samara’s world championship claims emerged. On December 11, Samara took two falls from Ted Germaine in a “rough and tumble” affair that lasted just 21 minutes. The Globe described Samara as a “heavyweight wrestling championship claimant” two days later. The paper stated that Samara was recognized by Gordon’s Massachusetts Wrestling Association, Inc. (MWA) and the hitherto unknown governing body — the United States Wrestling Association (USWA).

If the USWA existed, there are no records of it before its first appearance in the Globe. Given the nature of “governing bodies” in the area, the USWA title was likely defended under specific rules, which differentiated it from other claims. Bowser’s AWA title operated similarly in the area, with local champions required to challenge Bowser’s best to AWA rules matches.

Paul Bowser created the AWA and named his own champion, too, so why were his claims more credible than Gordon’s? As the situation on the ground in Boston looked — not much.

While Bowser’s group was the unquestioned king of Boston wrestling, the Gordon promotion was no slouch. His promotions regularly attracted crowds of 4,000+ to the Boston Arena, with some events reaching the 5,000 capacity. With a steady stream of New York talent, a dedicated following, and a boxer’s mentality, Gordon’s MWA was no pushover — and Bowser knew it.

The same Globe article also noted that Samara was eager to have his status clarified and was willing to prove his credentials by taking on both Everett Marshall and Yvon Robert, two leading grapplers, on the same night, without pay. Gordon planned to bill Samara as the true champion of Boston — which, in effect, was accurate, as Bowser’s AWA title lay vacant after Yvon Robert failed to meet challenger Lou Thesz in Los Angeles earlier in the year.

While a Thesz victory on December 29 ended the confusion surrounding the AWA title, the shouts for Samara continued to grow — and Bowser was feeling it. He brought Thesz to Boston on January 14, 1938, as an attempt to counter-program the popular Gordon crew running at the Arena. The writers at Globe smelled the fear in Bowser, noting on December 29, 1939, that “Mr. Bowser has finally recognized the penetrating wails for the meeting between the Negro champion, Seelie Samara, and some member of the Garden forces.”

Indeed, Bowser planned to meet the Samara threat head-on by sending his toughest men to end the troublesome pretender at the Boston Arena. The man chosen for the job was Billy Bartush, largely considered one of Bowser’s “policemen,” and the date for the match was January 19, 1938. (A policeman was an extremely skilled and dangerous wrestler who was used to keep potential threats to a promotion’s champions away by defeating them (or at least severely injuring them) before they could get to the champ.)

The “selection of Bartush to meet Samara,” said the Globe on January 14, 1938, “is in line with the long-established policy of dispatching a policeman to answer the claims of a rival promoter, a task for which, the boys say, the rough Mr. Bartush is eminently fitted.”

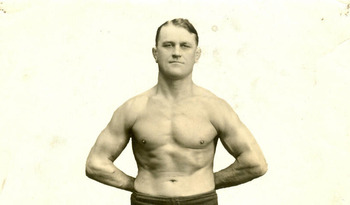

William Bartush was born in 1908 in Chicago to Lithuanian parents. He was a promising athlete early on and became a collegiate wrestling champion at the University of Chicago. Upon his admission to the pro ranks in 1929, Bartush quickly gained a reputation as a feared shooter and an all-around tough customer. Samara was in for a battle — or was he?

You see, Billy Bartush wasn’t nearly as fearsome as he sounded in the press. In fact, he had a long-established relationship with Gordon’s ally and talent supplier … Jack Pfefer. Pfefer had used Bartush from very early in his career, including donning a mask as the “Man of Mystery” in 1930. When the match finally came, Bartush was no match for the reigning USWA champ, dropping two falls in short order.

After Samara’s handy victory over Bartush, Tor Johnson was presented as the next daunting challenge for Samara. Johnson, “the mammoth Swede of the Bowser forces,” as the Globe wrote, was an imposing figure thanks to a 6-foot-3, 400-pound frame and a cue-ball shaved head, but, like Bartush, had a track record of working with Pfefer. He had competed earlier in the year on a wrestling card heavily laden with Pfefer talent card at Turner’s Arena in Washington, DC. His opponent? Billy Bartush. Johnson would later be one of Jack Pfefer’s famed “Angels” as the Super Swedish Angel.

There was a contentious finish to the Johnson-Samara matchup, as the Globe noted on February 9, 1938 that the city censor had some very strong words for Charley Gordon: “if any such aftermath as followed the Samar-Johnson bout occurs again, your license will be suspended or revoked.” The championship reign of Samara was igniting passions in the city — and packing the Arena weekly.

After defeating Johnson at the Arena on February 2, Samara again faced a fearsome foe from the Bowser clan — Hans Steinke. Steinke was a formidable German heavyweight who had risen to prominence earlier in the decade. Again, Steinke had Pfefer connections, as he had operated under the management of Pfefer’s ally, Rudy Miller. And, again, Samara was victorious in a quick effort — topping Steinke in two straight falls (and 22 minutes) at the Arena on February 23, 1938.

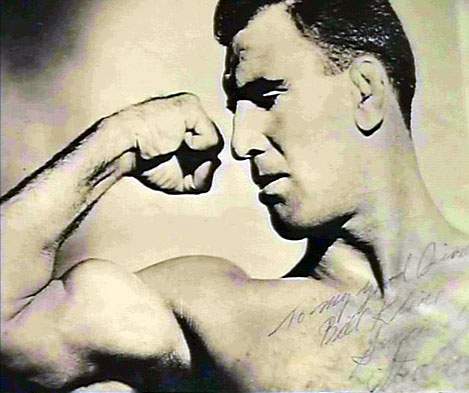

Steve Casey.

Seelie Samara had defeated Bowser’s forces at every attempt, solidifying his claim as the Heavyweight Champion of the World. But Bowser would not be beaten, choosing to stake his own champion, Steve “Crusher” Casey, against Gordon’s champion, winner takes all. Casey had beaten Thesz for the title earlier in the month, and Bowser wanted to make a quick splash, allowing his hero to knock off another pretender on his way to global mat supremacy.

The match was set for March 13th at the Boston Garden. Newspapers across the country carried the ANP Newswire bulletin on March 10, 1938 announcing the upcoming Casey-Samara world title clash, stating that “the first official world’s heavyweight wrestling championship featuring a Negro challenger is cooking on the fire right here in Boston amidst the delightful aroma of baked beans and brown bread.”

The same bulletin noted that Bowser was “the veteran who owns the more veteran and All-Star presentations at the Garden” but that “you know these Gordons; they are natural fighters.” Gordon and Samara had shaken the hornet’s nest and bested the nastiest of the creatures that answered his call. Now, the best-of-the-best, “Crusher” Casey, son of an Irish bare-knuckle boxer, was here to settle the score, once and for all.

If the pre-match hype grabbed national headlines, the match garnered little notice outside of Massachusetts. Instead of newswire bulletins and bold headlines, the results of the Steve Casey-Seelie Samara match only graced the bylines. Samara was defeated decisively in two straight falls, succumbing to a “side arm chancery and press” for the first fall at 27:35 and a “side army lock and leg trip” for the second and final fall at 9:41 later.

Samara’s shot at the AWA title, and his mysterious USWA World Heavyweight Championship, were no more, but this was hardly a sad ending for either Seelie Samara or George Hardison. In fact, he was still recognized by the Globe as the “ruler of the Gordon wrestling clan.” The same March 31, 1938 article notes him as the “lethargic title holder of the St. Botolph St. Guild,” indicating that he still held his MWA championship title — although the title is never mentioned again after this date. 8

While Samara’s title claims disappeared as confusingly as they appeared, it’s tricky to gauge how much traction the Samara USWA title claim held. The USWA was likely a set of rules to govern the match, as Bowser’s AWA operated similarly.

While the old saying “wins and losses don’t matter in wrestling” is hardly accurate, in this instance, it was. Samara was an endlessly popular figure with the New England crowds. His run demolishing Bowser’s best before ultimately succumbing to the world champion had only further established these sentiments among New England wrestling fans.

His first appearance after the Casey defeat only demonstrated further his local popularity. Some 5,000-strong made it out to the Arena on March 31, watching Samara defeat old foe Ed McNeil in a special bout, third from the top of the card. Bookings also expanded, with Samara working dates with Bowser at the Garden, Gordon at the Arena and the Old Mechanics Building (his secondary arena in Boston), and throughout New England. Hardison wrestled over 30 matches in the area — including battle royals — before bookings suddenly dried up after June.

George Hardison as Seelie Samara. While this image is from later in his career, it provides a good example of Samara’s strong physique.

Free Agent

But George Hardison’s dwindling bookings weren’t a sign of a failed career or of an ex-champ who just couldn’t make the grade anymore. Instead, Samara was on to bigger and better things. In the meantime, as his Gordon bookings dried up, Hardison subsidized his wrestling earnings by working as a truck driver. 9

Given the abrupt halt to his career in June 1938, one has to wonder what caused Gordon to stop using his biggest attraction. The answer was likely money, as it was an issue that occurred a few times over Hardison’s career. Realistically, Hardison saw the money that champions like Casey were earning and felt he deserved a bigger stake — and in many ways, he was correct. The likely pixie in his ear telling him he could earn more? Jack Pfefer.

Questions about whether Hardison was under the Pfefer umbrella were definitively answered when Samara returned to action in December in New Jersey, the heart of Jack Pfefer territory. It was a relationship that would see Samara travel across the country, becoming a fan favorite and headliner everywhere he went.

Next Time: George Hardison blazed trails and packed houses from coast to coast. We’ll take a look at the long, winding career of George Hardison, the successes he achieved, the hardships and injustices he faced, and the legacy he forged for future generations.

RELATED LINKS

- Part 1: Seelie Samara a forgotten African-American great

- Part 2: Seelie Samara a star around the world

- Part 3: The final years and legacy of Seelie Samara

- Part 4: Big George: The origins of Seelie Samara

FOOTNOTES

1 — Fort Valley, GA. US Census. Year: 1920; Census Place: Fort Valley, Houston, Georgia; Roll: T625_263; Page: 10A; Enumeration District: 44

2 — “‘Tiger’ Flowers Booked to Box Main Go Here” The News Messenger. Fremont, OH. February 23, 1924

3 — Massachusetts, U.S., Marriage Index, 1901-1955 and 1966-1970

4 — “Hardison Family Tree” Ancestry.com. Provo, UT. Accessed February 2, 2023

5 — Burke, Tom. “Yarns of Yesteryear: the Changing Thirties” The New England Independent

6 — In the Annotated Fall Guys: the Barnums of Bounce, Steve Yohe and Scott Teal do a great job both presenting the facts of this amazing scenario, while debunking some of the myths. Tim Hornbaker’s Capitol Revolution: The Rise of the McMahon Wrestling Empire is another excellent resource for background on this era.

7 — Some of Samara’s early results are courtesy of WrestlingData.com.

8 — His last date is listed against Paddy O’Day, who the Globe described as “Charley Gordon’s latest find” on June 21, 1938

9 — Greenfield, MA. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995. Ancestry.com