Al Zinck, a former amateur wrestler turned pro, and a boxing and wrestling promoter in Atlantic Canada, died on Sunday morning. He was 91.

Many of the tributes to Zinck, who died on April 7, 2024, after battling dementia for years, will refer to his time as a promoter, primarily in the 1970s and into the early 1980s, but the fact is that he never would have gotten to that position without a good solid understanding of the basics.

He was a fighter to the end, said his only son, Shane. Al Zinck was moved to long-term care at Camp Hill Veterans Memorial Building during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it was quickly realized that he was a handful.

Familiar with what happened in a nursing home in Minnesota where legendary shooter/wrestler Verne Gagne accidently killed another resident in 1999, Shane advocated to his sister, Krista. He said, “Krista, they’re going to have to get somebody on that floor with him who knows wrestling or Judo or Jiu Jitsu or something.”

Like his father, Shane Zinck could put up a fight, and wrestled very briefly in the 1990s. “They didn’t do it … and he had a couple of times there in that home there with some people, we got phone calls that he hit somebody or something,” recalled Shane, who had been estranged from his father for a few years. “He tried to escape one day and it was four or five security guards that headed [to look for him, and] he took a few of them out before they could subdue him.”

Al Zinck was born on January 27, 1933, in Halifax, Nova Scotia. With five brothers and one sister, he was the only one who was really into sports big time.

His father spent his life in the Canadian Navy, mainly as a cook. At one point, he was the chief cook at the Stadacona Barracks, feeding up to 5,000 service members a day.

It was his father that introduced him to boxing and wrestling, including boxer Gene Tunney and “Cowboy” Len Hughes, who was the Maritimes’ most popular wrestler and behind the scenes was the promoter.

At age 14, Al Zinck started amateur wrestling at the Halifax Wanderers Grounds, outside, and at the gyms at the YMCA and the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. Often, the amateur bouts were open to the public.

“At that time, there wasn’t much around the city, so wrestling was pretty popular,” Zinck said in 2009. “We were truly wrestling, amateur wrestling.” While there might be a pro bout or two on the cards, the amateurs didn’t share in the money, as their share would go to the club.

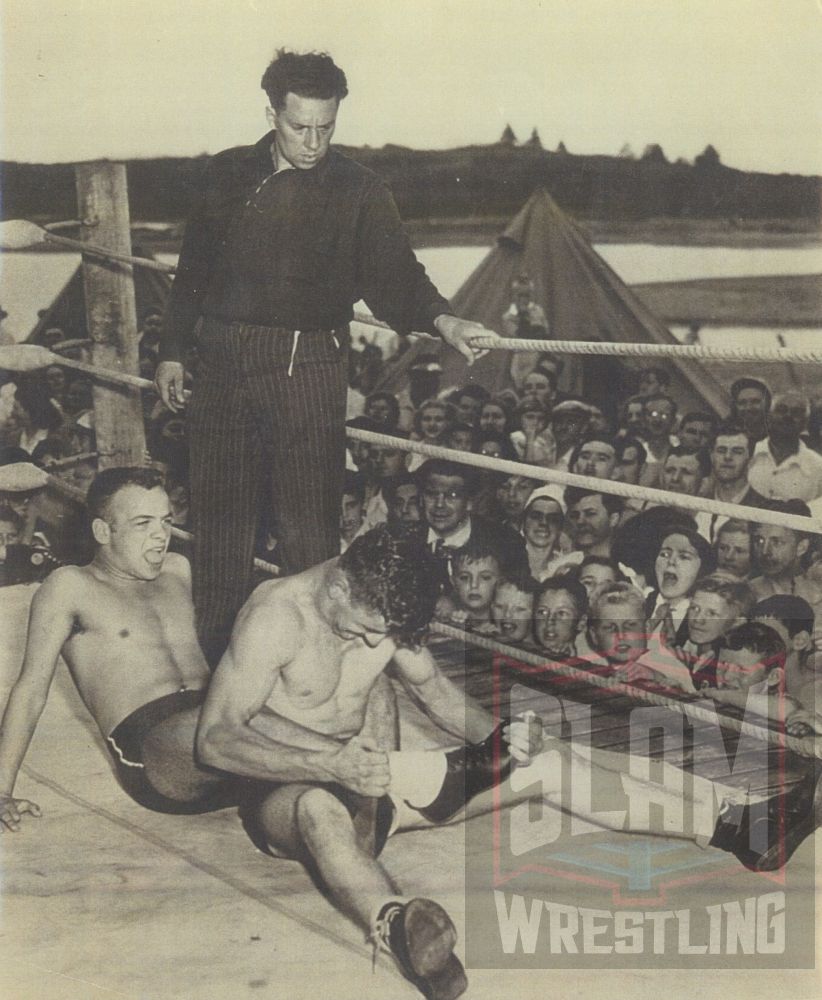

Al Zinck in action, as he is being bent by Ron “Bingo” Mayfield as referee Curly Aguire looks on, during matches held at the “Dockyard Picnic” in 1949.

His father’s old friend, Hughes, saw potential in a few of the amateurs, and helped Zinck, Billy Taylor, Ralph Morse, Reg Hamilton, and Len Brisco turn pro.

While Zinck was paid for a bout in 1951 as “Kid Zinck”, but he doesn’t consider that his career as a pro began until about 1954-55. “We used to wrestle for Len in 1951, but that was out of town. We used to sneak our way into getting paid. Those early bouts of pro wrestling were out of town,” he said.

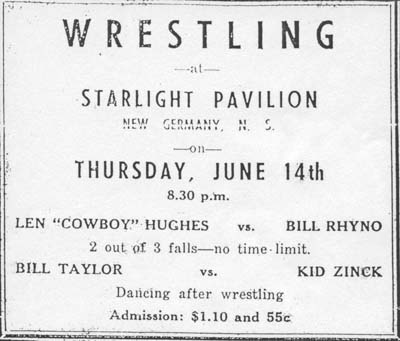

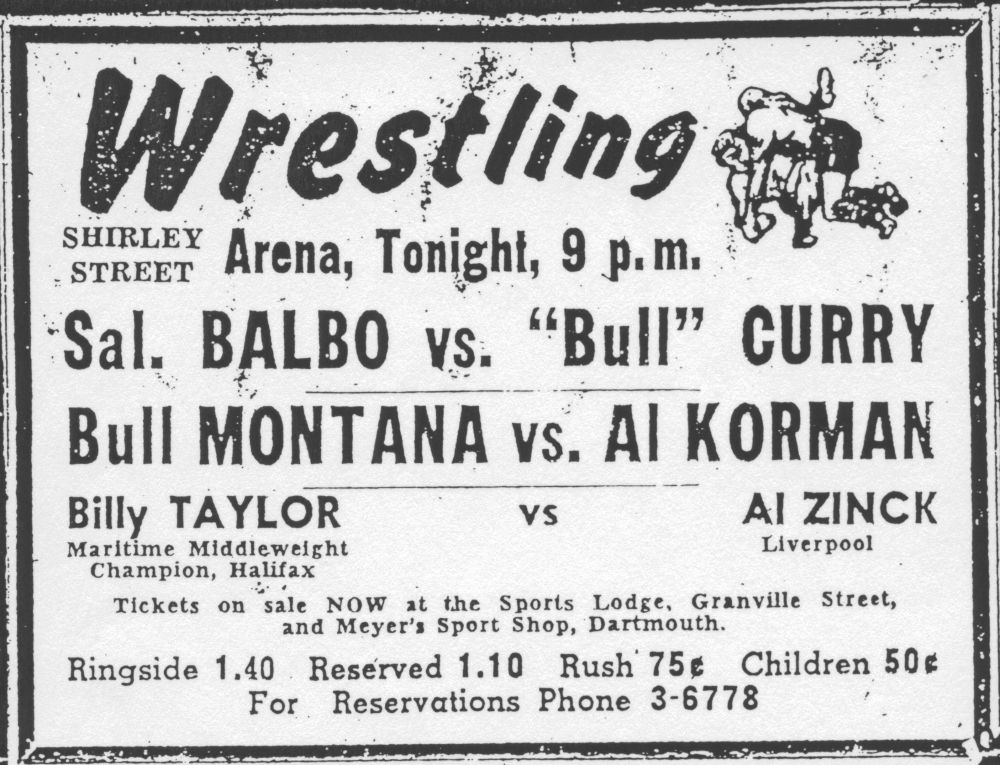

A 1951 Halifax card.

A bodybuilding and health fanatic, Zinck also studied for a time at Bill Pearl’s gym in California, and, in Toronto, around 1954, he worked out at the YMCA and made boxes at Massey Harris.

Zinck was not a big man and had zero issue admitting he was never a main eventer: “Nothing like that at all.”

Al Zinck on a 1951 show.

Upon returning home to Halifax after a few years on the road, Zinck enrolled at the Technical University of Nova Scotia (which later merged with Dalhousie University), where he studied plumbing. Again, the road called, and Zinck worked in remote locations like Goose Bay, Labrador, and on NORAD bases. Eventually, he got a full degree in mechanical engineering, plumbing and heating.

He kept up the amateur wrestling, and a little pro action here and there, and refereed. “In 1961, I wrestled Billy Taylor at the Halifax Forum for Len Hughes. I did a couple of matches as well as refereeing, same as Billy … we were on opening bouts. Then I was on a semi-final against Ossie Timmins at the Halifax Forum,” recalled Zinck. He enjoyed training amateur wrestlers at the YMCA.

It’s notable that Hughes had stopped promoting in 1964, and Emile Dupre and partner started up. But that fizzled out without a proper TV deal and come 1969, there was an opening.

It was as a plumber that Zinck was brought back into the pro wrestling business.

Rudy Kay, who was a part of the Cormier family with The Beast, Leo Burke and Bobby Kay, ran into Al when Zinck was on a plumbing job in 1968. According to Zinck, Kay said “Al, you ever thought about being a promoter? There hasn’t been any wrestling around here lately. Al, if you’re ever interested, I’d like to show you the tricks, show you the ropes, what to watch for, how to do up your gate control sheet, and all that stuff.”

Zinck: “Are you kidding? You don’t sound serious.”

Kay: “Al, I think you can do it.”

Zinck’s said he’d think about it, and eventually he and Kay worked out a partnership to begin what became Eastern Sports Association (ESA) in 1969.

“Rudy, he stayed in the background. He didn’t want nothing to do with the company, okay? So I did it all on my own. I formed a company called Eastern Sports Association presents International Wrestling. I had that name throughout United States and Canada, copyrighted, to protect me against fellows like Emile Dupre. And I wrestled for Emile Dupre one time, up in Bathurst, back in the early ’60s,” Zinck once told this writer.

From here, it’s a he said/they said situation.

“Al Zinck was just a frontman. Rudy was the one who was running everything. At the time, Rudy was wrestling and he didn’t want everybody to know that he was involved in promotion. So he used Al Zinck as a frontman, but he ended up thinking, his head got big, and he thought he owned everything. They went half and half on the promotion part of it,” Bobby Kay once said. “He did a good job, but he didn’t have a clue what he was doing. That wasn’t his fault. He was a good-hearted person, I guess. As far as running a business, he didn’t know. If you said something was black, he’d say it was white. Not that he was a bad person, it’s just that he didn’t know and he was too stubborn to admit it. Maybe he thought he knew, I don’t know. Like us, we were in promotion all over the world all of our lives. We had a pretty good idea how things should be done.”

Les Thatcher was one of the wrestlers the Cormiers brought into ESA. Thatcher said that Zinck didn’t understand that he was just the promoter. “He was too big for his britches. He wasn’t one of the boys, but he came across like he was,” explained Thatcher. “He’d hear us talking carny, and he’d act like he knew what we were talking about. Of course, we knew he didn’t. … He was a mark for himself.”

An oddity in the pro wrestling business, Zinck detested foul language. “They called me The Preacher … I didn’t come down to their level,” summed up Zinck.

But boy oh boy did International Wrestling mean a lot to Atlantic Canada, running in the summer months (usually May to late September) until 1975 with Zinck/Kay, at which point Bobby Kay ran it for a season.

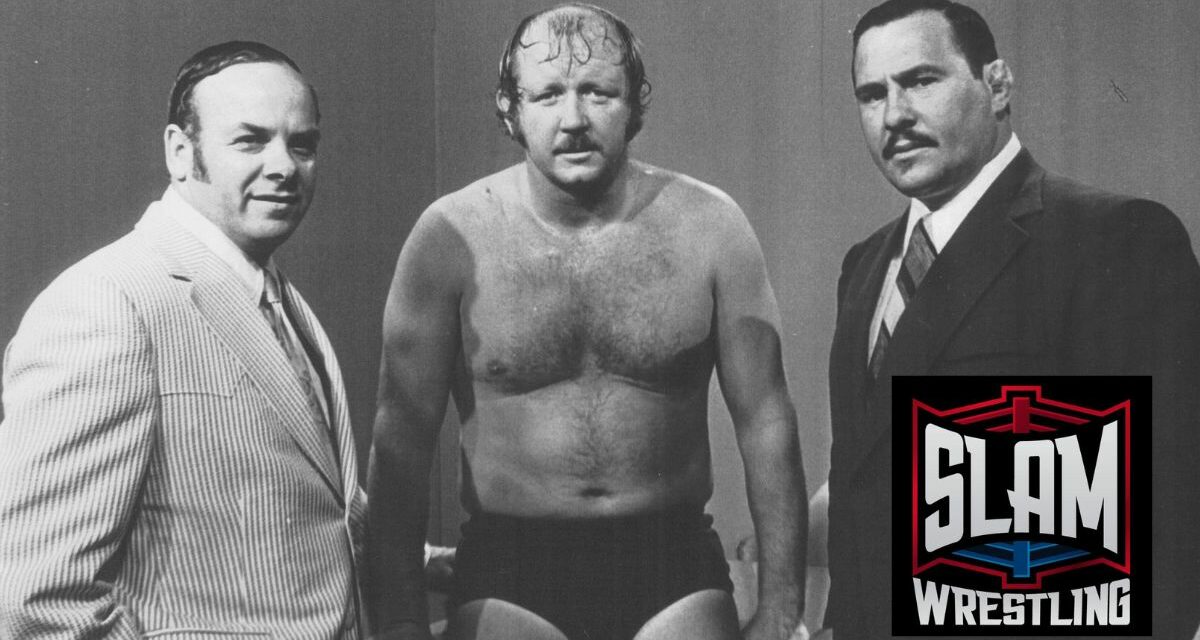

A program featuring Al Zinck, Clary Flemming and Rudy Kay.

The weekly TV show, taped on Wednesday mornings on CJCH-TV in Halifax — following a house show on Tuesday nights at the area’s biggest arena, the Halifax Forum — became a staple of Canada’s eastern provinces. (“He got the first TV show by luck,” once said Dupre of Zinck.) The tours were matches every day, but the towns weren’t that far apart, money was decent, and there was the stunning scenery, friendly people, and food.

Host Clary Flemming became part of the culture. “Wrestling was his big break,” said Zinck. “Clary was a good, straight-level pro.”

“I put up every doggoned cent. I paid to bring every wrestler in here. I most certainly did,” insisted Zinck. “I had to mortgage my home, then I had to re-mortgage my home again because our gates weren’t coming up — until we got the TV over. Once we got the TV over, after about six weeks, then the gates started to climb. The first years, I was mortgaged to the hilt. Rudy never put one cent into it, not one. My wife was worried sick. I drove a taxi that winter. But when I opened up in 1970 — we started in 1969 — and when we opened up in 1970, gee, I couldn’t believe it. We played our tapes about six weeks in advance on TV before we opened, and the crowds, they just started to come. What a relief.”

A behind the scenes shot of International Wrestling from a program includes, left to right standing, Ed Brown (producer), Larry Knoke (program manager), Al Zinck (promoter), George Flie (scriptwriter), and Curly Aguire (timekeeper), with George Cannon (commentator) and Johnny Wall (ring announcer) seated.

NWA World champion Harley Race came in for a week, and recalled it in a SlamWrestling.net chat: “Truthfully, the week I enjoyed up there was very enjoyable. I met a lot of great people and ate a lot of lobster. If I had the opportunity to go back, I’d go back.” Other NWA World champions like Dory Funk Jr. also came in.

The Cormiers would bring in their friends from territories where they worked in the rest of the year, like Charlotte, Texas or Stampede Wrestling. You’d have Johnny Weaver and Tommy Gilbert come up for a summer each, whereas villains like Freddie Sweetan, Mike Dubois, Killer Karl Krupp, Jim Dillon, and others might come back for a program every summer. Plus, there were many young talents that got opportunities out there, including some of the first matches for Rick Martel, Roddy Piper and Terry Gordy.

There’s a reason that Kay and Zinck didn’t last. According to Zinck, “Rudy had no business head.” He was also “soft with the boys, but I wasn’t.” Especially the prelim guys; “I want my openers to be as good as my main eventers.” That was a lesson he learned from Hughes, said Zinck.

Then it fell apart. “Rudy double crossed me when I was in the hospital,” said Zinck, who had fallen off a horse. “When I was in the hospital, Rudy asked for checks, and like a fool, I signed them.”

Without Zinck, who made the TV deals, the Cormiers eventually had to stop promoting. Emile Dupre, who had promoted at times in competition to ESA, ramped up after the promotion folded, and controlled the territory for the 1980s.

As a boxing promoter, Zinck had some success too. Former WBC World heavyweight champion Trevor Berbick was a youngster who had moved from Jamaica to Halifax, where he got into boxing. “I was the first one to have him. I started him,” once bragged Zinck, launching into a story.

“I got rid of him. I had six months to put up with him. Tom McCloskey carried on a little further. Tom was about the best trainer in Canada, bar none,” said Zinck. “I washed my hands of [Berbick] … I tore my contract up right in front of him … He would never, never, never listen. That man would never listen. We had our problems. We had to beg to get him out there in the ring to fight. But when he got out there, he could fight.”

Dave Downey was another Halifax boxer that Zinck managed for a time. According to Zinck, Downey once backed out of a big fight against Joey Durelle, and Zinck had to refund $85,000 in ticket sales.

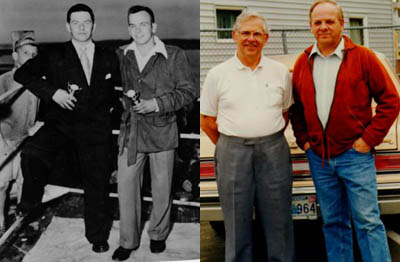

But it was wrestling that ran in Zinck’s blood. He kept in touch with many old pros, including his old buddy Billy Taylor. Not one to hold a grudge, Zinck attended the 2006 fest of all things Cormier in New Brunswick.

Billy Taylor and Al Zinck in 1950 and in 1995.

With his engineering background, he built wrestling rings. Zinck loved to brag about them, figuring he made 14 total. “My masterpiece belongs to WWE, Vince McMahon. I sold it to Ted Turner for $7,000. It’s got 3/8 plywood fiberglass sheeting, and it locks together in the center, and it bolts together in the center. You put the ring together in 35, 40 minutes. It’s all cable steel, the ropes are cable. It’s the first time they ever had this type of ring. He made duplicate copies off of it to go on the road.”

When the Toronto promotion run by Jack Tunney switched allegiances from the NWA and Jim Crockett Promotions to the expanding World Wrestling Federation, Zinck saw an opportunity. It was Zinck who ran WCW shows in Toronto and in the Maritimes. [See REVISITING NWA/WCW’S RETURN TO TORONTO IN JUNE 1990]

Zinck worked with WCW/NWA from 1989-1993. “I was always a straight shooter … I almost had Maple Leaf Gardens. I was so close,” he claimed. “I was ready to under cut Tunney.”

Shane Zinck can still recall the way his father would get into trouble as a promoter. “I used to go to the wrestling with him in the circuits. And every once in a while I’d get a call to over the PA system. ‘Shane Zinck, please go to the office,'” he said. “I’d only be a kid, like eight, nine, and he’d be beating up five or six guys who to attacked him. And I mean, he cleaned house on them. He was a real scrapper.”

There’s no question that some of his father’s stories got embellished through the years, said Shane. Since Al would be asked about the NWA/WCW all the time, the tale started to include him meeting owner Ted Turner, when that never happened, said Shame.

Al Zinck was a man of many interests — and surprises. At various times, he was a drummer in a Halifax pipe band, an award-winning photographer, and even studied opera in Boston for a short while. “I loved it. I like to sing opera arias,” said the tenor. He ran a stable at Miller Lake, with dressage the main focus, with about 40 horses.

Zinck was married to Tootsie over 50 years. Tootsie was short for Josephine. “They call her Tootsie because her father says she was born with her feet in her mouth,” chuckled Shane Zinck. Tootsie is still alive, but is also confined to care, with dementia.

Al and Tootsie had six children, in order: Cindy, Carla, Krista, Alexis, Shane, Natasha.

Funeral arrangements are not known at this time.

TOP PHOTO: Al Zinck, Dory Funk Jr. and Rudy Kay.

RELATED LINK