The stories are certainly varied about the death of Freddie Sweetan at age 36: His barbecue exploded; He was shot; He fell asleep with his cigar still lit; His charcoal grill fell over. The fact is that he died alone that summer day back in 1974 at his little shack in the woods in New Brunswick, and no one will ever know the exact details of his demise.

Thirty years later, the memories of his fellow wrestlers may be a little clouded in regards to Sweetan’s death on July 26, 1974, but his impact on their lives comes back very easily.

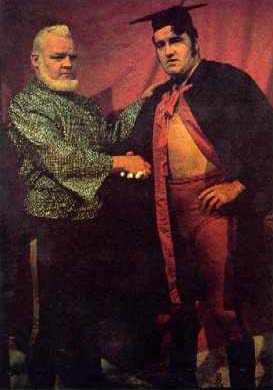

Freddie Sweetan, left, and Michel “Le Justice” Dubois. Courtesy Pat Casey

“You couldn’t ask for a nicer person, that’s the gospel truth,” said Eric Pomeroy, who first met Sweetan in Kansas City. “He was a hard worker, good performer in the ring, really a nice person. I couldn’t say anything bad or detrimental towards him. He was down-to-earth. His word was his bond.”

“Freddie, as far as I’m concerned, was a real, real man,” said “The Beast” Yvon Cormier. “He was a big, tough wrestler, but he was the type of guy that wouldn’t lie or wouldn’t take advantage of anybody else. That’s the type of guy he was.”

Freddie Prosser was from Shenstone, in Albert County, New Brunswick. He was a big kid — 6’2″, 260 pounds — who could handle himself if needed.

“He was a raw-boned kid. He was really rough looking,” said “Stompin'” Paul Peller, who would team with Prosser under masks in Stampede as The Butchers in 1968. (Sweetan was Butcher No. 1, Peller No. 2.)

Peller had met Prosser in New Brunswick, however. He had started his own wrestling career in 1961, and sought out Emile Dupre to school his new friend, Sweetan.

“I’m the guy who started him out,” Dupre recalled. “He lived quite close to Shediac. He lived in Hillsborough, which is about 40 miles away. Paul Peller introduced me to him and told me that he was interested in breaking into the business. We had a gym set and we started working out.”

Prosser’s first big break was under a mask in the winter in Calgary, teamed with Peller. “I thought we had made the right combination,” said Peller, who considers their championship run in Stampede the pinnacle of his career. “They gave us a chance and we proved it. By proving it, we started drawing big. We sold out four weeks in a row in Calgary and Edmonton. We had matches against the football player Bob Luce and Emile Dupre. We were drawing big.”

After Calgary, Prosser followed the lead of other Maritimers like Peller, Dupre and Leo Burke, and returned home for the beautiful summer circuit that frequented the small towns and cities. “He’s from the Maritimes and loved the Maritimes,” said The Beast. “He came every summer. He was a good performer, he did a good job,” remembered Dupre.

In 1969, Prosser was back in Calgary, but this time without the mask. Promoter Stu Hart decided to team him up with another rough, rugged brute of a wrestler — “Bruiser” Bob Sweetan — and make them brothers. With his new bleached blond hair, Prosser learned from the veteran Sweetan, who had been in Calgary off and on since 1965. They were a good, solid team, recalled Stampede promoter and photographer Bob Leonard. “Bob always had good heat here (had a long tag run with Gil Hayes), and Fred fitted right into things. Bob tended to be the bombastic loudmouth, Fred more the strong, quieter brute of the pair.”

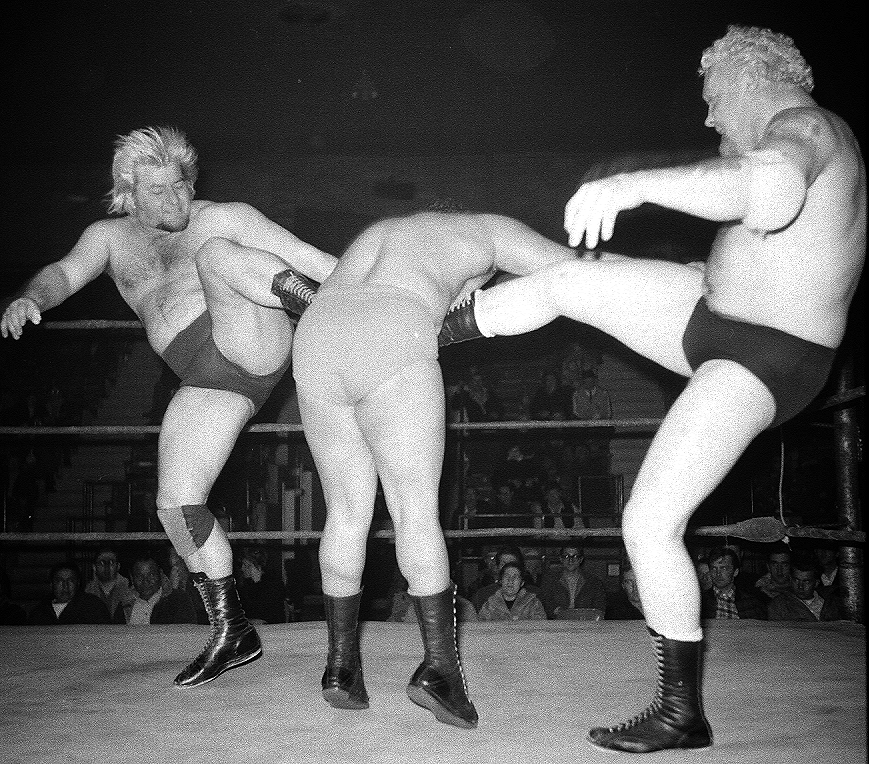

Fred Sweetan and Paul Peller in Stampede Wrestling. Photo by Bob Leonard

Sweetan and Burke got Prosser hooked up into Kansas City, where he was Killer Cox, brother to K.O. Cox (Bob Sweetan). “He wrestled for us a long time down here. He was a hell of a performer too,” recalled Central States part-owner Bob Geigel.

But “Bruiser” Bob Sweetan and “Stomping” Paul Peller aren’t the only partners that Prosser gelled with over the years. He teamed with The Beast one winter in Texas, and in a few locations, he battled alongside Michel “Le Justice” Dubois. “Nobody was better, to me, than Michel ‘The Justice’ Dubois and Freddie Sweetan,” said Leo Burke.

Bob & Freddie Sweetan lay in the boots in Stampede Wrestling. Photo by Bob Leonard

Fan Donnie Mason recalled seeing Sweetan and Dubois faces the likes of Terry & Bobby Kay, George & Sandy Scott and Big Boy Brown & Klondike Bill around 1973 in Virginia. But a five-match run that Sweetan & Dubois had with the Royal Kangaroos really stands out for Mason. “It was the wildest and bloodiest series I EVER saw,” he said. “Everything was done to perfection, buildup, finishes, the whole nine yards. It was a true classic. The funny thing was this was a feud that only ran here in Lynchburg. There was no buildup from TV. It all started here as a Battle of the Bullies and it just took off here for a 5 match run that packed the Armory. To this day I still can not figure why the bookers never took the hint and built something for the whole territory. I know it would have done big money if they put on the shows they did here.”

But for the folks in the Maritimes, the pairing of Prosser and Pomeroy comes up most often. “[Pomeroy] and Freddie Sweetan made a real good team, a super team,” said The Beast. “God almighty, me and Rudy [Kay] wrestled them quite a few times, and me and Leo, here in the Maritimes, when we clashed together, the people just sold out the places.”

The late referee and wrestler Ossie Timmins wrote about a Beast-Sweetan battle in a column in the Whatever Happened To… newsletter in November 1999. “I remember a strap match a few years later in Berwick between the Beast (Cormier brother) and Freddie Sweetan. They were both bleeding freely. As I looked at their faces, there was no color … only an ash gray look on their faces. Me … I was covered in blood, and so was the white canvas. It made me think of a time when warriors fought to their deaths. I couldn’t wait to have a shower and head for home.”

Pomeroy consider Prosser like a brother, and his voice cracks as he recalled the last days of his friend and partner, which were not peaceful at all.

The Newfoundland-born Pomeroy, who also worked as Stan Vachon and Stan Pulaski, recalled a conversation with Prosser’s father. “His father was sitting in my motorhome. We were somewhere up there… I said to him, ‘How you feeling?’ He said, ‘Oh, I don’t feel good. As a matter of fact, I think I’m just going to go home and shoot myself.’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘No, I’m serious.’

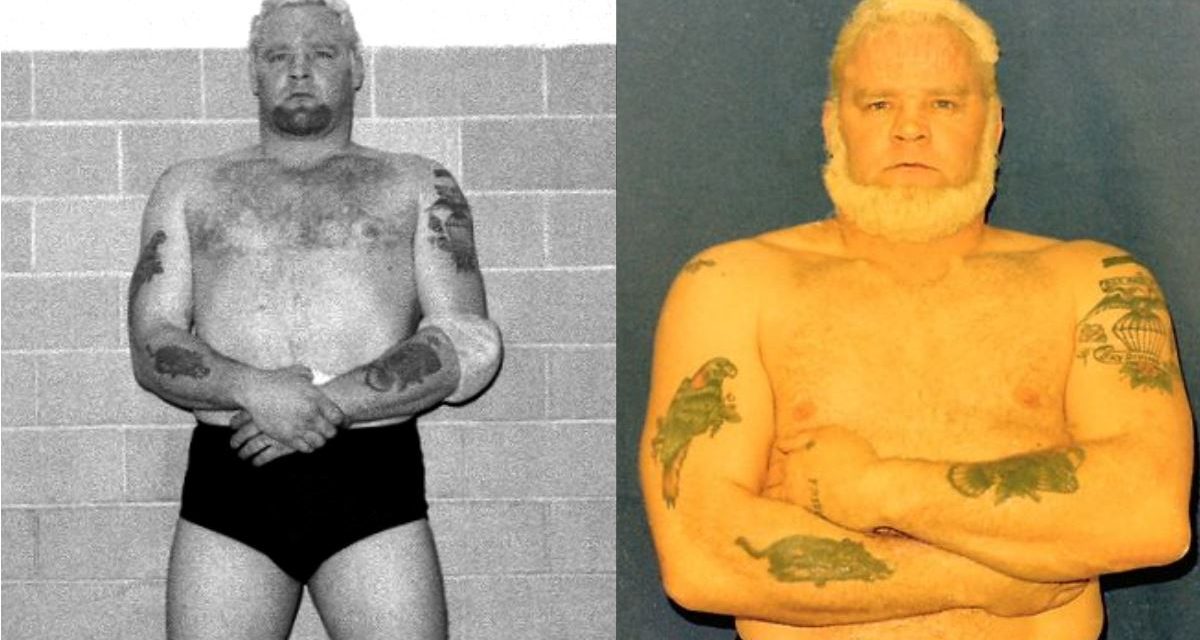

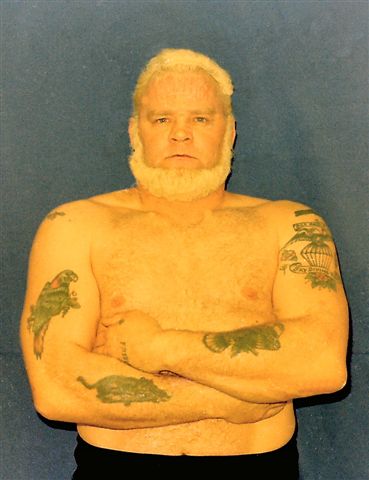

Freddie Sweetan. Photo by Dave Drason Burzynski

“I’ll be a son-of-a-gun, when we came back that night, there were four or five Mounties waiting for me at my trailer. Freddie was in my car. A Mountie walked over to me and said, ‘Fred, why don’t you stay in the car a minute while I talk to Mr. Pomeroy.’ I get out of the car and go over there. That’s where he told me that Freddie’s dad had shot himself. He took a gun from the house, sat down by a tree, took a stick and flipped the trigger, pushed the trigger and shot himself. They had a lot of trouble getting to him because Freddie had a dog down there … the dog was right beside him and they had to tranquilize the dog to get to his dad.”

It wasn’t that long afterward that Prosser died in his cabin at his summer camp at MacFarlane Bridge, 15 miles southeast of Moncton.

“It’s a shame what happened to him. The saddest thing is that I feel bad myself. I always felt bad about it,” said Pomeroy. Prosser had a small party planned at his cabin on the Friday night, but Pomeroy wanted to go to his motorhome near Moncton to get a good night’s sleep before doing an interview the next day.

“We were wrestling that night in Saint John, New Brunswick. It was Freddie’s birthday. We went to wrestling,” said Pomeroy. “When we came back, he said, ‘Why don’t you come on down to the lake’-on the river down there, he had a little house down there where we’d go fishing. He said ‘We’re going to have a little party down there in the cabin.’ I said, ‘I’ve got to go. I’ve got to go early in the morning to Moncton. I’ve got an interview. Then I’ll meet you down there before the matches. Freddie, I just can’t.”

Prosser and his buddies went down to have their party, with a fire and barbecue. Undoubtedly, Prosser had a celebratory cigar or two (a vice recalled vividly by his friends). “What they think happened is, after everybody left, he sat at the table there, probably with his cigar or something. He fell asleep, the cigar fell down and caught the place on fire,” said Pomeroy. “The whole place burned right to the ground. When they found him, he was right by the door. He was strong enough. He was like a bull. He could have walked through the walls. The Mounties thought that maybe smoke had stopped him from getting out of the building.”

Dupre heard it a little differently, and said a barbecue was to blame. “It was one of these charcoal things. They stay hot for quite awhile. Apparently, he fell asleep on the table or something, maybe had a few beers. I don’t know the whole story, but it was told to me, that’s what happened.”

The news story in the Halifax newspaper (where he is called “Prossner”) references the barbecue explosion. “An RCMP spokesman in Moncton said last night that Sweetan died in the blaze, which besides destroying his camp, burned his late model car parked nearby,” read the obituary. “The spokesman declined to reveal circumstances surrounding the blaze.” An autopsy was performed at the Moncton hospital. (Sweetan had been advertised for a July 30 show in Halifax against Bobby Kay in the July 27 newspaper, and the match was removed in the July 28 listing.)

As such a close friend, Pomeroy was asked by Prosser’s mother to look after the funeral. Freddie Prosser was cremated and buried in the same plot as his father.

Pomeroy offered up one last what if. “If he hadn’t have died, I’m telling you, he was young enough that he probably would have went on and made some big money in the business.”