One can’t tell the history of professional wrestling in the Maritime provinces without talking about “Cowboy” Len Hughes, who was one of the first major stars in the area he became an influential promoter.

Or in the words of one of his protégés, Emile Dupre: “He was the one that really started the ball rolling here.”

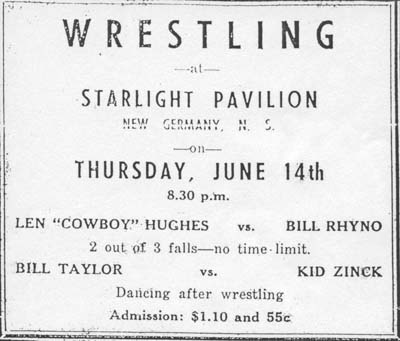

Len Hughes in a classic Tony Lanza posed handout photo

Leonard Richard Hughes’ story begins in Cisco, NY, in 1908, the son of Merton Edith (March) Hughes, though he grew up in Northampton, Massachusetts, near Springfield, where his father apparently worked on a trawler further east. Despite Springfield being the cradle of professional basketball, it was professional wrestling that would win the heart of the 6-foot, 225-pound, strong husky athlete.

He was wrestling by the 1930s, a migrant worker, heading from town to town, and seeing lands few others did. Hughes made at least three tours of England, and was one of the pioneer wrestlers to head into Cuba, under the promotional auspices of famed boxer Jack Dempsey, who had the connections to make it happen in the pre-Castro nation. His opponent in that main event in Cuba was Angelo Savoldi. “He was a tough boy,” Savoldi remembered of his long-ago foe. “He was just a tough guy to wrestle, let’s put it that way. He knew how to handle himself. … always a smile on his face, but inside the ring, he was Cowboy Len Hughes.”

In the 1930s, a man known only as the Masked Marvel debuted in Atlantic Canada. According to Al Zinck, a fan turned wrestler then promoter, “his mask reached the bottom of his neck. His trunks and wrestling boots were of different colors and his long leg tight pants. All in all he was quite colorful.”

Wrestling in Halifax was a weekly feature during the summer — generally the third week of May until the second week of October — at the old Halifax Arena, which was on Pepperell Street. The next location was the Shirley Street Arena, placed, appropriately, on Shirley Street.

According to Zinck, the Masked Marvel continued to wrestle during a second summer in the Maritimes, but “Cowboy” Len Hughes also competed as well. Eventually, fans clamored to have the two heroes fight.

That impossible plan was derailed, however, by Sal Balbo, another fan favorite. “He managed to get the Masked Marvel in a reverse chokehold around the neck, locked him in under the armpit with his left arm and hand, untied the lace with his right hand, under [Hughes’] neck,” recalled Zinck. “Balbo pushed him into the ropes, the mask came off as he was ready to dropkick him. The mask was in his right hand. The crowd went wild when the mighty Masked Marvel was revealed to be none other than their hero Len Hughes.”

The fame of Hughes only grew from there. He would drop the “Cowboy” nickname while fighting in the Maritimes in the summer months, but keep it while on the road during the rest of the year.

“The Spoiler” Don Jardine was one of those who hero-worshipped Hughes. “He wasn’t fancy, but he was good,” the late Jardine recalled in 2006.

A 1951 Halifax card.

“He was truly a hero among local sports fans,” wrote columnist Al Hollingsworth in the Halifax Daily News after Hughes’ death in 1984. “When Len Hughes came to town there was a little extra hype given the matches”

“Len, it seems, was a born wrestler and one of the astute people you could find in the ring. He could rough it up, and usually did, but he also knew all the clever tricks of the trade and could hold his own with any rival when the action was on the mat,” wrote Ace Foley in the Halifax Chronicle-Herald in 1983.

The heroic figure didn’t necessarily translate away from Canada’s east coast. “He goes all out to win regardless of the rules, regulations, or referee, and many times is disqualified because of this,” reads a Wrestling U.S.A. magazine from April 1954.

“Another guy that worked me over was Cowboy Len Hughes. I don’t know if the office told him to do that,” explained Danny O’Sullivan (Jim Wyatt) in the first Shooting With the Legends book. “He treated me like a rag. Every time I’d get up, he’d start beating me again.”

Hughes continued to wrestle up until the late 1950s, even though his prime was clearly over. During that time, Hughes went to work for Larry Kasaboski in the Northlands Wrestling promotion in Ontario. “Larry had worked for [Hughes] in Halifax in the mid-40s,” recalled historian Gary Howard. “Kasaboski always looked after his friends. Len didn’t have much spark left by that time. One of Larry’s weaknesses was his loyalty to the old guys who were over the hill….he gave them one last hurrah.”

Long-time fan Terry Dart remembers Hughes working around London, Ontario, as the 1960s began. One incident still makes Dart laugh. “I had a guy in a headlock in the parking lot, and the guy was whining and moaning. He said, ‘Here comes Cowboy Hughes. Wait’ll I tell him!’ I said, ‘Oh, I’m in trouble now.’ Hughes comes along and he looks at me. He said, ‘What are you doing?’ I said ‘Putting a headlock on the guy.’ Hughes said ‘You’re not doing it right.’ Hughes takes my hands, clips them together and said, ‘There, that’s the way you put a headlock on. Now keep him in it.'”

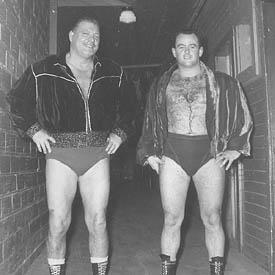

Len Hughes and Bud Cody in London, ON. The Terry Dart Collection.

After a stint in the United States Navy during World War II, Hughes got involved in the promotional end of things in the Maritimes, partnering with Clary Harris and Alvin Brown, who owned a furniture store in Halifax. Harris and Brown also promoted boxing.

“Len Hughes was the one that knew all about wrestling, but these guys had the money,” recalled Dupre. “They were three partners running the business, they were the investors. I want to tell you, they did great, until Clary Harris got cancer and passed away. The other guy, Brown, was strictly the bookman. When that happened, he wasn’t interested. I was wrestling in those days.”

Hughes would help inspire and start numerous wrestlers over the years, including Billy Taylor, Al Zinck, and O.J. ‘Ossie’ Timmins.

Those that worked for Hughes said he was fair. “He was alright with me. A lot of guys didn’t like him. He was an ex-wrestler,” said Hans Schmidt, who said Hughes paid well. “There was no doubt about that; he always did pay me.”

Very early in his career, Dominic Denucci worked in the Maritimes for Hughes. “From what I remember, I never had any problems with the money or anything. What he promised me wasn’t a guarantee, but he paid,” said Denucci.

Hughes used his connections made over the previous years to book good talent, and knew a thing or two about getting the word out about shows as well. One of his stunts was to drive around Halifax in an open convertible, using a megaphone to advertise the matches that night. Often, the star of the evening, like Whipper Billy Watson, would be in the car as well.

The story of Hughes’ departure from the promoting ranks around 1965, in part because of his bad knees, is different depending whose side you hear. Both Dupre and Zinck would go on to be promoters in the Maritimes for many years, Dupre with his Atlantic Grand Prix, and Zinck with International Wrestling, in conjunction with the Cormier family.

First up, Dupre. Around 1964, Dupre, having made a very good living on the road as “Golden Boy” Dupre, decided to get involved with promoting himself at home. Brown wanted out, and he stepped in as a partner to Hughes.

“To make a long story short, I invested money with Len Hughes,” said Dupre. “Another guy invested too. The thing was dead, then all of a sudden it started booming. We brought in Watson and Gene Kiniski. I remember being on my knees to bring the little midget girls. He said, ‘Why would people want to see that?’ He couldn’t understand that. We brought them in and drew $7,000 in those days with the small prices, $7,000 in Halifax. Moncton was $4,000, where we had been drawing $1,000, $1,200. He said, ‘I don’t understand, how come that can draw?’ I said, ‘That’s attractions that they’ve never seen before.’ He couldn’t see through that. He had lost it. The business went great until the end of the summer. I was getting paid like a wrestler. At the end of the summer, when it came time to settle up for my investment — I hadn’t put in a million dollars, I had only put in $5,000 in the deal. In the middle of the summer, he gives me my $5,000 back. Now he had a cushion, he’d made money. At the very end of the season, I asked, ‘What did I get for my investment?’ He sat down with a bunch of papers and showed what all the expenses were. He settled up and I had made some money. ‘But,’ he said, ‘that was for one season only. It isn’t for next year.’ Now that the thing was on fire, it wasn’t for next year. It was morally wrong, but business-wise it was good, which is okay, that’s fine. It seemed to me that when a guy invests, he should be included next year now that the ball is rolling. He said, ‘Maybe that’s your point of view, but that’s not mine.’ I said, ‘Okay, that’s fine.’ That’s when I became a promoter, right there and then. That was his downfall. I put him out of business.”

As Zinck tells the story, Hughes found out about Dupre going behind his back to the arena managers, and fired him.

Hughes faded from the scene, but not from the Maritimes, which he had grown to love. He had married a local girl named Christine MacLellan — “Kitty” to everyone — not long after getting involved in promoting. The couple did not have any children. Initially, they lived in a trailer at the bottom of South Street in Halifax, on the shore. When the land was sold, they moved the trailer to Nine Mile River, near Timberlea. Their first home was in Allen Heights, until failing health forced the Hugheses to go to Shoreham Village in Chester.

On Christmas Eve 1984, Hughes passed away. His death barely made a ripple, lamented Hollingsworth in the Halifax Daily News. “Wednesday, a 15-line account of his death was carried at the bottom of page 35 in the Chronicle-Herald. Len Hughes had passed away on Monday at the age of 76,” he wrote. “And while he is gone from our midst, those of us who shared his corner for so many years, will never forget the pleasure he brought to our lives.”

A cat story that’s not for cat lovers

Bob Geigel was in the Maritimes in 1952 or so, and was friends with Len Hughes. Len’s wife Kitty had a cat, and while driving home one night, Geigel saw a cat that looked just like Kitty’s. Determined to play a rib, he shot the cat and took it to the Hughes’ trailer, where he strung it up outside the door. Later, Kitty emerged and screamed, thinking that her cat had been brutally killed. Geigel told her it was a rib, but it took a long time to convince her. The next time he was in the ring with Hughes, Geigel recalled him saying, “You’ve gone too damn far,” and that the match was “a little more rugged” than usual.