Recurring payments you set and forget are an unfortunate part of modern life. Whether it’s your cell phone bill or your streaming service, seeing that chunk of change debit out of your account each month can be frustrating – especially when it’s a subscription to a newspaper archive. Fortunately, this month, I got far more entertainment than I bargained for. Intrigued? Read on.

While thumbing through records for Texas in the early 1950s, I came across something odd – and it involved one Johnnie Mae Young.

Mae Young

Mae Young is someone all wrestling fans know of – but few really know about. And I throw my name into that uninformed list. Sure, I knew of her wrestling, notoriety, and exploits with the Fabulous Moolah during the Attitude Era, but there was much I had no clue about – and I am not alone.

Young was a challenging character, part sweet, part spicy, but full of chaos with an indomitable spirit. As one reporter so eloquently put it in 1948, “Mae Young, the gal of a thousand moods and grimaces does a good job of out Dr. Jekylling-and-Mr. Hyding the famous Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

For example, I recently learned she was a preacher in the late 1940s. And I want to cover another lesser-known Mae Young role today – one she briefly held in Paris, Texas. For you see, in late 1950, along with an associate by Eva Lee McDevitt, the name of Mae Young added another hat to her collection: wrestling promoter.

But the story of a small, short-lived promotion is far less interesting than the whirlwind partnership of Eva Lee and Mae Young, two names inextricably linked to some of wrestling’s most infamous moments.

BORN TO RAISE HELL

Growing up a tough tomboy in Sand Springs, Oklahoma, the young Johnnie Mae initially found fame on the school’s varsity sports teams – both the boys high school wrestling and football teams – in addition to being a standout softball player with a championship team based out of Tulsa.

But her challenge to women’s champ Mildred Burke in the late 1930s drew her towards the professional wrestling ranks, as recounted in Greg Oliver’s career retrospective on Young from 2014 after her death.

According to Young’s story, she went up to the promoter and outright asked for a match with Burke. Though she was denied her request, it planted a seed. In other retellings, Young instead wrestled Burke’s opponent, Glady “Killem” Gillem, and quickly dispatched her in a shoot.

The following decade is somewhat hazy, but it’s clear that Young spent much of the 1940s crisscrossing the country and establishing her name as one of the toughest female wrestlers in the game at that moment – and potentially of all time.

TROUBLEMAKER

But there were also run-ins with the law, a testament to her take-no-prisoners mindset. In 1945, fellow woman wrestler Elvira Snodgrass talked about how Young got into trouble in Little Rock, Arkansas, one night. “Young is a natural roughneck,” said Snodgrass. “This night in Little Rock, she said something to a man fan, and he kicked her in the face. Then Mae took him. His wife came to his assistance, and Young sent both of them to the hospital.” The aftermath was a trip to the jailhouse for Mae and a fine.

By the early 1950s, Young already had legendary status in the wrestling business – with a list of accomplishments as long as her rap sheet. She also had extensive connections, particularly in Oklahoma, Texas, and Louisiana, making a promotional gamble logical.

But who is her partner? Who is Eva Lee McDevitt?

Eva Lee McDevitt

EVA LEE: MORE THAN JUST A PRETTY FACE

As always, the promotional materials and press coverage are essential for cracking the mystery. According to the Alexandria Town Talk of Alexandria, Louisiana, on her debut in that city in February 1951, Eva Lee was “attracted to professional wrestling from a financial angle, being a successful businesswoman herself.” At 26, she was already busy with an eight-year-old daughter and a successful restaurant and cocktail lounge in Houston, run by her mother while she was wrestling.

The public records provide a little more clarity – but not much. It appears Eva Lee was born sometime around 1924 in Texas, the daughter of Lee R. Loftis and her mother, Gladys. Eventually, Gladys separated from Lee, marrying a man named George Nelson, with Loftis eventually moving to Colorado City, where he died in 1955.

There are a few references to Eva Lee in childhood. A May 1939 article in the Houston Chronicle made note of the upcoming “state jitterbug championships” at the City Auditorium. The contest would see sectional champions battle it out to see who exactly was the jitterbugger in Texas. One of those contestants was a young 14-year-old, “Ms. North-side,” Eva Lee Loftis. It seems the young Eva became an equally young bride, marrying a Neale E McDevitt that same year – July 1, 1939. She would have been 15 years old at the time of the marriage, which we know likely produced one child, a daughter, around 1943. How long the marriage lasted is unknown, but it’s clear that by 1950, it was finished, as Eva Lee was residing with her mother and stepfather.

Eva Lee Loftis gets married, July 1, 1939.

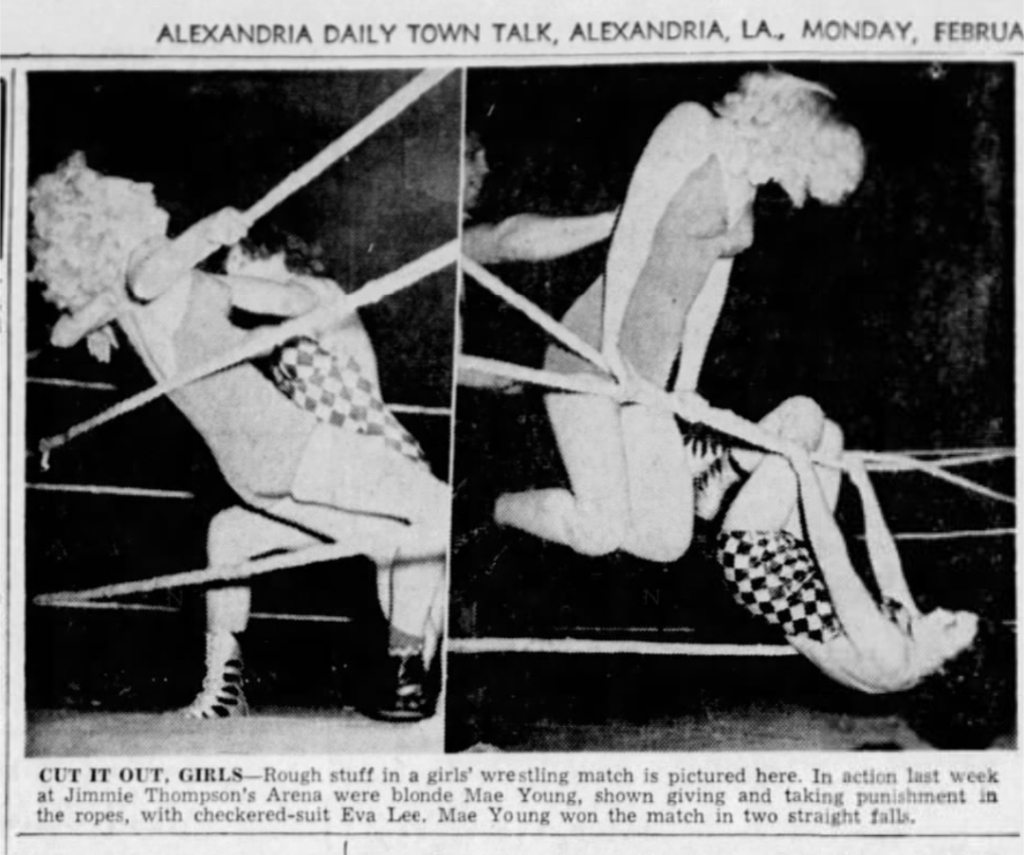

As a wrestler, Eva Lee was graceful, quick, and scientific. That grace was due to her previous success as a fencer, with a lighter frame giving her a speed advantage versus other opponents, including Young, on that evening. The two were constant in-ring rivals, facing off so frequently in Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma during the period that it would make Diamond Lil and Darling Dagmar blush.

Eva Lee’s run with Mae Young appears relatively short, allegedly from 1948 until the pair parted ways sometime around 1952. Despite this, the relationship – whatever its true nature – certainly left plenty of lasting memories.

DEATH OF A SALESWOMAN

In the ring, there was the ultimate tragedy, with both Young and McDevitt taking part in a bout that saw the death of Jeanette Wolfe, the adopted daughter of women’s wrestling kingpin Billy Wolfe.

Jeannette, born Janet Boyer, was from Minnesota but found her path after begging promoter Wolfe for a shot at grappling, claiming to have “never met a boy who could beat me.” The kingpin, liking her spirit, took her under his wing, with the pair eventually becoming so close that Wolfe formally adopted the young woman.

The tragedy occurred at Patterson Field Stadium in East Liverpool, Ohio, on July 28, 1951. Jeannette worked an opening match with Ella Waldek, getting pinned after a fierce slam. Returning to the dressing room, she complained of a “busting” headache,” but returned to the ring later that evening, partnering with Eva Lee vs. Mae Young and Ella Waldek.

The press described the rest:

She tagged Eva as a signal she wanted to be relieved. Eva jumped into the ring, and Jeannette started to walk away. Then she collapsed on the ring apron, clutching one of the ropes. She never regained consciousness. Jeannette died in Osteopathic Hospital in East Liverpool on Saturday.

According to a grief-stricken Billy Wolfe, the body slam probably caused a cerebral hemorrhage, something backed up by the coroner.

Of note, Waldek and Young would play up their roles in the incident later in their careers, aiming to use tragedy to show their in-ring cruelty.

STAY OUT OF RENO

Outside of wrestling, it would appear that the two women were opposites. Eva Lee was a successful Houston-based tavern owner, while the always-outspoken Mae Young was a barnstorming grappler from the old school, matching slick in-ring skills with legendary toughness and tenacity – and a heaping pile of carny.

It just seems like an odd fit. Johnnie Mae had a fearsome reputation, including tales of seducing and assaulting lonely businessmen and then helping herself to their money. That’s a tough life – one a young businesswoman was sheltered from.

However, mugging businessmen is a dangerous side hustle, so it’s best to have help to avoid getting overwhelmed, just like Salvador Manriquez, a Sacramento-based cafe owner.

On the bitterly cold evening of January 29, 1948, Reno police discovered Manriquez battered, bloody – and barefoot off a secluded, snow-covered Reno road. Disoriented, Manriquez told officers that he met a trio of women in the Bank Club earlier that evening, amidst a 26-hour gambling spree. From there, the party continued throughout the night, before he blacked out after leaving his drink for a moment. He had then awoke half-naked, freezing, and $1,100 lighter.

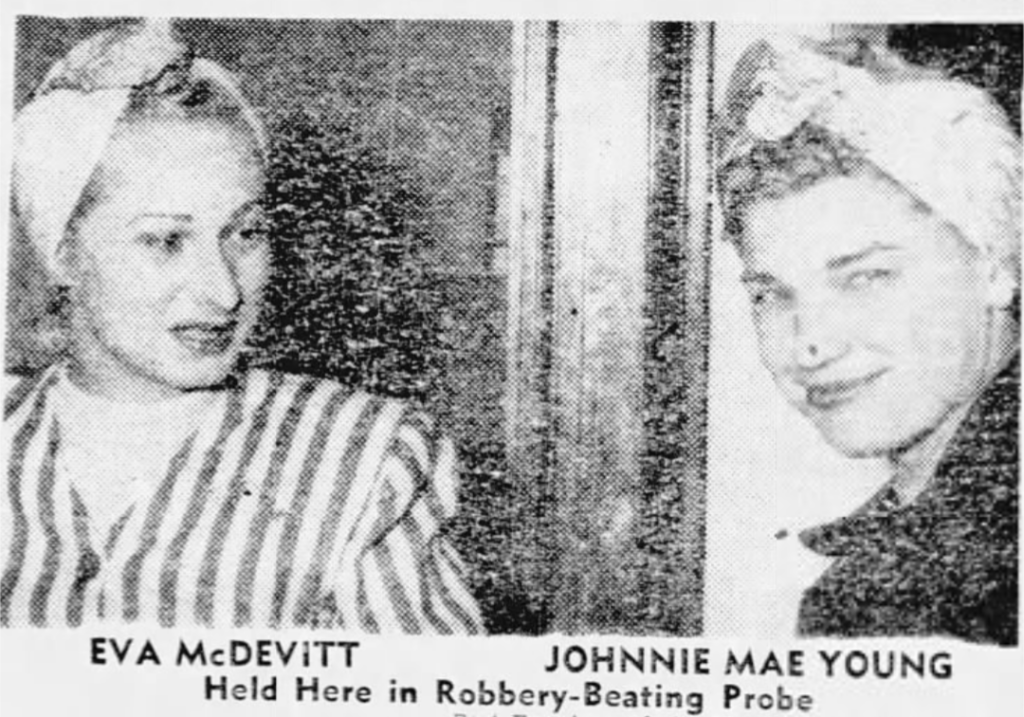

Arrests were soon made. The accused? Johnnie Mae Young, 28, described as a wrestler and evangelist; Mary Anise Huse, 22, former barmaid and night club photographer from Monrovia, Alabama; and Eva Lee McDevitt, 24, Houston bar owner.

Mary Anise Huse, Eva Lee McDevitt, and Johnnie Mae Young in court in Reno, NV.

Mae Young was residing in Oakland at the time of her arrest, working as an evangelist preacher. As recounted to SlamWrestling.net by Young herself, “Well, my sister was involved in the church, and I went out there and got involved. I became an evangelist. I worked for two or three years as an evangelist.”

That story is further fleshed out by a July 6, 1948 profile in the Chattanooga Daily Times: “It was Christmas before last,” Mae told reporter Edna Wells, “that I witnessed the faith healing of an old man paralyzed for 18 years. This Incident played a big part in bringing me into the church known as the Body of Christ in Oakland, California.” Young even went so far as to claim over 150 conversions in just one night of her preaching.

And she was serious about her beliefs – at least for a while. The thrust of Johnnie Mae’s evangelical efforts was to raise funds for a church and school, something she sought to accomplish through preaching and grappling. “The dream of my life is to build a wonderful temple, with a school in connection, where those who wish Christian training may attend free of charge.”

She was supposed to be “back in the grunt and groan business just long enough to raise money to build a church and a school. Just where the missing money from Manriquez ended up is a mystery.

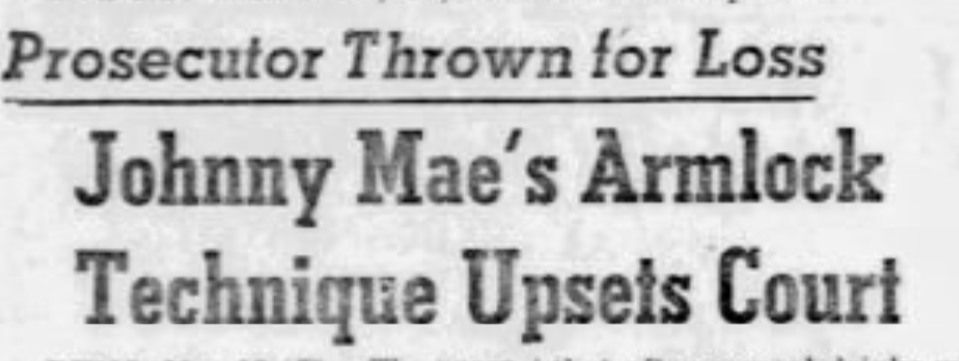

The trial, as expected, quickly devolved into farce, with plenty of wrestling interspersed. According to the women, Manriquez was overly amorous, getting a little too friendly in the backseat of Eva’s card for the liking of Mary Huse – the focus of his lothario lusts. For his trouble, he got a slap, a glass bottle to the face from Huse, an arm bar, and plenty of kicks from Young. The women then jumped back in the car and fled into the desert, later telling authorities that they opted not to file a rape charge because of Johnnie Mae’s wrestling career.

The prosecution highlighted numerous holes in the women’s tale. For starters, there was the issue of the missing $1,100 Manriquez reported to police. The women claimed it was theirs, but prosecutors wondered why the money was covered in blood – had they used it to defend themselves?

According to Huse’s police statement, she had gone into Manriquez’s pockets looking for keys. But on the stand, her story changed. The reality, she claimed, was that she had reached into her pockets looking for a scarf to wipe the blood off her hands from the struggle, and the money just happened to be in there; hence, it was bloody.

So, what was the cause for the discrepancies in her testimony? The policemen must have misunderstood her in the confusion, right?

Mae Young demonstrated her armbar in court on May 18, 1949.

Then, there was the matter of a letter Huse had written (but not sent) while in jail in Oakland after her arrest. The letter, quoted in court, stated, “I know damn well these western Yankees don’t like us southern rebels. Everybody gives me a big rib about holding the sack. I’m mad as hell I didn’t get the loot.”

Oops.

Fortunately, Huse had a response for this as well, explaining that this response was “jocular” and sarcastic and that deputy sheriffs “pestered her frequently about the case, and that she had told them the trio didn’t have any sack to hold.”

Surprisingly, the trio were acquitted on May 20, 1949. After this date, Eva Lee began appearing in the records as a wrestler. Maybe she got a taste for life on the wild side and liked it?

A wise man once said, “Fool me once, shame on – shame on you. Fool me – you can’t get fooled again.” Well, if the Manriquez was a case of non-consent, then the women certainly didn’t learn any lessons about choosing their casual acquaintances in the following months.

Just months later, there was a similar incident. Elmer J. Nelson met Young at a restaurant and went to town with her and a friend. Later, he was found beaten and robbed and sent to the same hospital in Reno, Nevada. The missing amount in this instance was $100. The friend? Mary Huse.

The duo were acquitted again, but Young would later let her story slip in a syndicated news piece, telling the United Press that “Maybe I did work Mr. Nelson over a little.”

PARIS PROMOTERS

Enough about the two promoters’ backstories; on with the story of their short-lived promotion!

Young and McDevitt appeared first as Paris wrestling promoters in November of 1950. The women had lined up Barrett’s Skating Rink as their venue, with the city’s normal venue, the Coliseum, closed for renovations. Their Tuesday night cards were to be the first in the city in several years.

Barrett’s Skating Rink

The cards the women promoted were a cavalcade of independent talent, a highlight of Texas wrestling in the era – a period that saw Ed McLemore in Dallas and Morris Sigel in Houston go to war.

Present, for example, is Otto Kuss, a name synonymous with midcentury independent wrestling as Thunderbolt Patterson in the 1970s and ’80s.

There was also Tommy Phelps, a Texas-born wrestler-turned-preacher (like Mae Young), who was, at this period, Jack Pfefer’s righthand man in Texas, serving as a messenger, scout, and liaison for the diminutive, eccentric, and itinerant wrestling tsar.

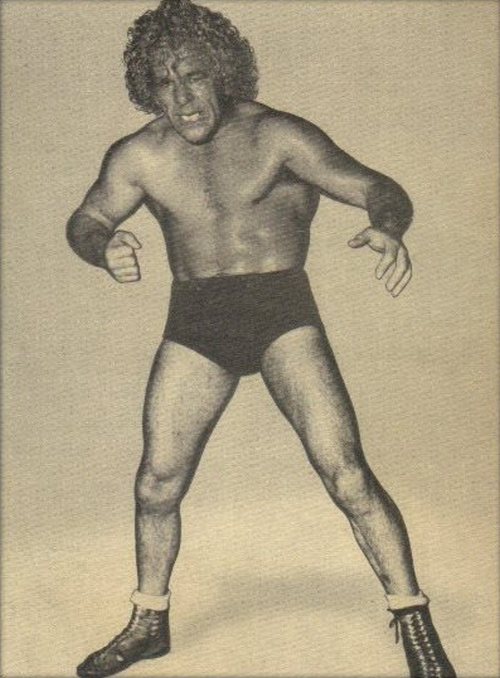

And speaking of Russians, there was Leon Kirilenko, The Mad Russian.” While not a Russian in the slightest, Kirilenko – or rather, Albert Rosburg – was a long-serving grappler who was fresh off spells as the Rocky Mountain heavyweight and Midwest junior heavyweight titles. But his gimmick, that of a madman, was soon to come true in the most horrid way.

Leon Kirilenko

The Milwaukee Journal on October 30, 1952, recounts the story:

Leon Kirilenko, 34, who wrestles professionally as the Mad Russian, was sentenced to one to two years Wednesday in criminal court for a crime against a child. He was arrested in August after police found a 9-year-old girl in his hotel room. Kirilenko denied that he molested the girl.

According to the allegation, Kirilenko met three young girls on a street corner playing when he invited all three to buy them milkshakes. Two girls refused, but a third agreed and went with the wrestler. After buying her a milkshake, Kirilenko invited the 9-year-old child to his apartment.

“Pearshape” Powell was another Pfefer talent, working under a slew of “imposter” names, including the next year (1951) as both “Bunny Rogers” and “Young Buddy Rogers.” Similarly, Phelps would spend 1951 as “The New Nature Boy” and “Nature Boy” Phelps – attempting to pick up the slack after Buddy Rogers’ departure.

It wasn’t successful.

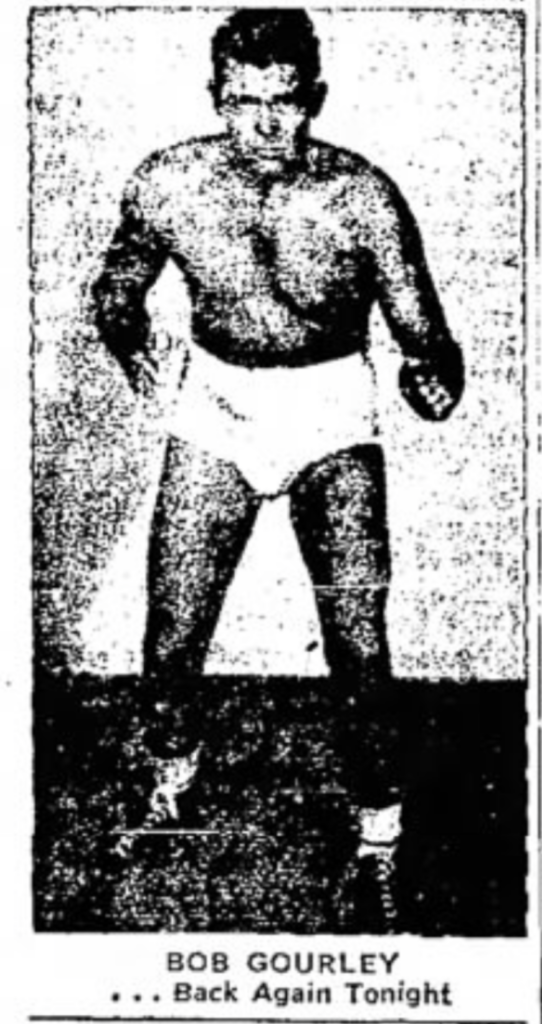

The other wrestlers on the card were two roughnecks, “Bad Boy” Brown and Bob Gurley, who “put the show off on its right foot with a one-fall brawl.” I’m not sure of the background of Gurley, but “Bad Boy” Brown was Jack Brown, another veteran of the ring wars who had been wrestling under that name since at least the early 1930s.

DID THEY SPOT A MONEY MARK?

But what’s really interesting about the Mae Young/Eva Lee promotion in Paris, Texas, is its brevity. The overall timeline is impressive, showing the pair promoting from 1950 into 1951, but in reality, it was just two shows. So, what was the plan?

The ultimate goal was to sell their stake – and quickly. As mentioned, the pair used the relatively small Barrett’s Skating Rink, hosting grappling on Tuesday nights. The rink wasn’t ideal for wrestling, but it was all available, with the Coliseum at the Lamar District Fairgrounds out of commission due to extensive renovations. The smaller venue hurt attendance, with the second show attracting a crowd of just 200.

The Coliseum in Paris, Texas

At the center of the renovations was a local promoter, Thad Davidson, who planned to expand the Coliseum to provide better acoustics, a false ceiling for better heating and cooling, and improved seating for over 1,000. He also planned to bring dances, wrestling, and other events to his new and improved venue shortly.

SELLING OUT

That near future was Young and Lee’s second card. An announcement was made at that card that Davidson, a local businessman, had purchased the Paris pro wrestling franchise and would operate the sport there after January 1, 1951.

The arrival of Davidson’s promotion saw further use of Pfefer’s talent. Beyond Kirolenko and Phelps, there was Abe Stein and Gorilla Macias, And if you need more proof that Jack Pfefer had his hands on the promotions? The Paris news reported, “The Mad Russian will take on Light Heavyweight Champ Vern Gayne.”

So, what was the reason behind those brief promotional efforts? Did they realize the Coliseum was being refurbished and would need wrestling shows to fill the calendar? Did they think they could make a go of it in an area starving for pro wrestling and eventually get brought into the fold with the Coliseum? Or did that want a quick payday and saw Thad Davidson as an easy mark to sell a “successful promotion” to?

I guess we’ll never know.

While their foray into promotion was brief, the partnership between Eva Lee and Mae Young continued through the year, with the pair competing against each other repeatedly across the southern United States. The pairing abruptly parted after a historic bout in Hammond, Indiana, on September 18, 1951 – the first women’s match to take place in the state after the state legislature overturned a ban on women’s wrestling only the day before.

Still, that’s a hell of a run for a relationship of roughly four years.

WHATEVER HAPPENED TO EVA LEE?

So, what came next for Eva Lee?

Following the long journey with Young, Eva Lee took up the equally arduous task of a player in the Billy Wolfe repertoire. This involved plenty of matches in the Midwest, particularly Indiana, Ohio, and Western Pennsylvania.

After her tour with the Billy Wolfe and Jack Pfefer circus in 1952, Eva Lee McDevitt disappears from the records. For a woman of such excitement, youth, and vigor, the lack of closure with the story of this intriguing young woman is frustrating, at best.

There are hints, but these are few and far between and riddled with conjecture. Perhaps the best evidence comes from a marriage license issued on August 3, 1956, in Richmond, Texas. On it, McDevitt wed one George William Howard, Jr., another Texas native. But here there is another roadblock with the future of Eva Lee and her daughter still lurking in the shadows.

THE CORONATION OF MOOLAH

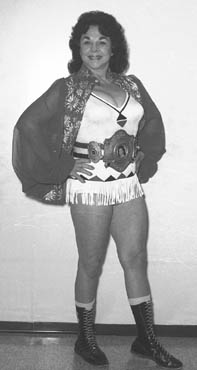

The story of Eva Lee and Mae Young, while incomplete, does provide a sort of full-circle closure regarding their being intrinsically interwoven in some of the biggest events in the history of women’s wrestling. Beyond the assaults, promotions, and being the first female wrestlers to compete in Indiana, the two were also part of the crowning of the sport’s “longest reigning” women’s champion – the Fabulous Moolah.

The Fabulous Moolah

Both Eva Lee and Mae Young were part of the one-night tournament that saw Moolah crowned women’s champ and presented with the belt now synonymous with her name. Held at the Coliseum in Baltimore, Maryland, the tournament included many of the biggest names of the day, including Mary Jane Mull, Carol Cook, and Judy Grable (the first one).

Despite the significant layoff, Eva Lee proved something of a success on the evening, facing off against former partner Mae Young and defeating her in the quarterfinals before finally succumbing to eventual runner-up Judy Grable in the first semi-final.

For most of the women in the tournament, the loss was just another bump in the road, but to Eva Lee, it proved the end of the road. There are no records of her after this date – her life slipping back behind the shrouding mists of time, where it’s rested for years.

Still, even without the proper conclusion it truly deserves, the story of Eva Lee and professional wrestling is more than full of the stuff of which legends are made. Hopefully, we can discover more about this fascinating entrepreneur, restauranteur, mother, and all-around colorful character of wrestling’s past in time.

NOTE: I would like to thank Steve Johnson for his assistance on this and other projects. His contributions to the research of this article were essential for finally getting to grips with the identity of Eva Lee. Now go read his article “Before the Iron Claw: the Origins of Fritz Von Erich,” it’s really, really good!

RELATED LINK