Lillian Ellison, better known to the world as The Fabulous Moolah, has died. She was 84. To more than one generation, Moolah was more than just a woman wrestler — she was women’s wrestling.

It’s hard to play down her accomplishments. After all, how many other wrestlers — forget just women — have been profiled in lengthy features in Sports Illustrated, as Moolah was in November 1974?

The Fabulous Moolah. – Courtesy of the Wrestling Revue Archives

She was women’s champion, as recognized by the McMahon WWWF and WWF for an incredible 28 years. Moolah controlled women’s wrestling, by training future grapplers at her Columbia, SC estate — where she died Friday night, November 2, 2007 — and then booking them in territories and promotions across the globe.

A member of the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame since 2003, Moolah was also inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 1995.

“Moolah was the epitome of any girl wrestler I’ve ever seen,” recalled Bill Kersten, the announcer in Kansas City for decades. “What made her so good was that she was another one of those people where you give them an inch and they were on you. She never would back down from any of the wrestlers, and she would take a bodyslam, and another bodyslam, and another bodyslam, and get up and whip back down anybody else. She carried on. There wasn’t three seconds that wasn’t action, which was unusual for a lot of the women wrestlers. They’d have to take a break during a match with a headlock or a leglock. Moolah was the queen.”

Ellison was born in a small community between Blaney and Pontiac, SC, the last of 13 children. Her mother died when she was eight years old. To help salve the wound of losing her mother, her father started bringing her to the wrestling matches. She fell for the sport big time.

The 5-foot-6, 135-pound Ellison began her career under the banner of girl wrestling promoter Billy Wolfe in Columbus, Ohio. However, it was a short-lived relationship — Wolfe apparently thought she was too small — and she moved on to work with promoter Jack Pfeffer.

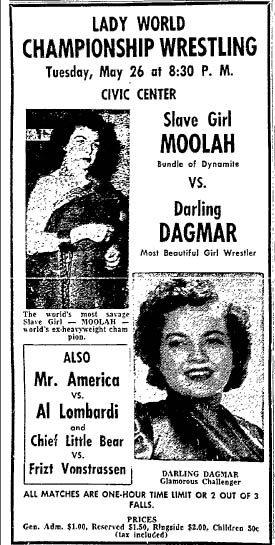

Under Pfeffer, she would accompany The Elephant Boy (Bill Olivas) as Slave Girl Moolah. The name stuck even after she moved past being simply eye candy at ringside. For years, when an interviewer asked about the name, Moolah would recount a little spiel:

“You like moolah?” asked the promoter/trainer, often referred to as Tiger Simpson.

“I love moolah,” she replied.

“Great, we’ll bill you as The Fabulous Moolah.”

Working with Elephant Boy, Moolah was a key part of angles and matches. “Elephant Boy, with the help of Moolah, won the first fall from Carlos Mendoza in seven minutes. The bushy haired “South African” used various choke holds to soften up his opponent and Moolah administered a few blows and held the Mexican on occasion while Elephant Boy pummeled him,” reads one newspaper report from Coshocton, Ohio, in 1952. “He started the same tactics in the second fall but Mendoza let go a haymaker that felled Moolah at ringside and then let Elephant Boy have one. The final fall went to Elephant Boy when he apparently was dazed by some flying tackles from Mendoza. As Mendoza came off the ropes for another, Elephant Boy let go a chop on the windpipe and quickly pounded the Mexican into submission.”

In a 2002 interview at the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion, Olivias alleged that he and Moolah were more than just partners for the audience.

“Wrestling was very good to me. I think that if it hadn’t have been for Jack Pfeffer, I might have been — is she in the room? — I might have been married to Moolah,” he said. “At first, Jack watched us very, very closely. In fact, he always had a room just down from us in the hotels. He would sneak down to Moolah’s room and Pfefer would knock on the door. He’d say, ‘Tony, Tony, I know you’ve gotta the Moolah in there. Come out of there. No lovey-dovey in here.'”

A 1953 clipping.

“The Elephant Boy was a sweetheart. My, did we have some fun on the road. Much of it was at poor old Jack Pfeffer’s expense,” Moolah wrote in her oft-criticized autobiography, The Fabulous Moolah: First Goddess of the Squared Circle. The book, written with Larry Platt, kept somewhat to kayfabe and revealed little about her iron-clad control of the women’s wrestling business. In a 2000 interview with this writer, she decried the difficulties of cramming 49 years in the business (and counting) into one volume. “Hey, 49 years is a long time!” she said. “It is so much. I know that I won’t be able to get it all in there, but I’m going to do my best”

Moolah was never a high-flyer, preferring a ground-based attack. “I know some dirty tricks and I use ’em if I have to,” she told the Washington Post in 1965. “But I leave all my hostility in the ring. I don’t stay mad when the match is over.” In the same article, she claimed to have earned a $100,000 salary in 1964.

Moolah’s crowning glory as a singles wrestler came in Baltimore, Md., on September 18, 1956, when she beat Jennetta Collins in an all-girl wrestling tournament to become the new Women’s Wrestling Champion — though she had been billed as a world champion in Pfeffer’s Ohio promotion. It’s an oft-repeated part of wrestling lore that she kept the title until 1984, losing to Wendi Richter in one of the angles that led to the first WrestleMania. In fact, she traded the title quietly with women in her organization on a few occasions, in never-recognized title changes.

In her hometown of Columbia, Moolah established a school for prospective women wrestlers. Many, many names went through her school, which was both a school for beginners and a place for polishing.

The late Sherri Martel once said that being trained by Moolah was like torture. “She was very strict, very demanding. She wanted perfection from you. She was the most phenomenal woman, but she demanded perfection from you and knew how to get it. I had a bartending job at night and had to be at the gym at 7 and what I didn’t tell you was I didn’t get off of work until 2.”

Moolah instilled in her charges the same love of the business that she had, and the same protectiveness. “She would do anything at all in the world to help the business, to make the machine run,” said Dutch Savage, who promoted with Don Owen in the Pacific Northwest. “She didn’t care what she had to do, whether she had to lose, whether she had to win, whatever she had to do, blade herself, she would do it, because she cared about the business.”

“Moolah, commanded, demanded and taught the female wrestlers how to have respect among the wrestlers while they were on the road. Look at the way the women dressed in the territory eras,” wrote seamstress Juanita Timbs — wife of Ken Timbs — in 2004. “Their suits had to fit in such a manner that their body parts didn’t fall out. I sewed and repaired outfits for the women. They were wrestlers and were expected to be viewed as such.”

For the last decade, Moolah was an irregular on WWE broadcasts, occasionally wrestling and sometimes just appearing in skits, often with her best friend Mae Young (who had a hand in training Moolah).

“As a person, she’s the greatest lady in the world,” Young said in 1993. “She’s been a real friend through the years. You can’t get any better than that. You can’t buy friendship. It’s the most wonderful thing in the world.”

In late 2005, she had knee surgery and lost 30 pounds.

Ellison’s first marriage was to wrestler Johnny Long, who really helped her learn to wrestle. They had one child together, Mary, who briefly wrestled as Darling Pat Sherry. Her second marriage, which lasted nine years, was to wrestler Buddy Lee, and together they started Girl Wrestling Enterprises, which filled the void left by Billy Wolfe’s death in 1962 and booked women wrestlers. Her third husband was not involved in the wrestling business. In her autobiography, Moolah also claimed to have almost married legendary country singer Hank Williams Sr.

RELATED LINK

- May 10, 2018: Complicated legacy of Fabulous Moolah on trial at CAC

Greg Oliver met Lillian Ellison on numerous occasions and always found her to be a Southern belle, but also pretty intimidating considering the small packaging. Greg can be emailed at goliver845@gmail.com.