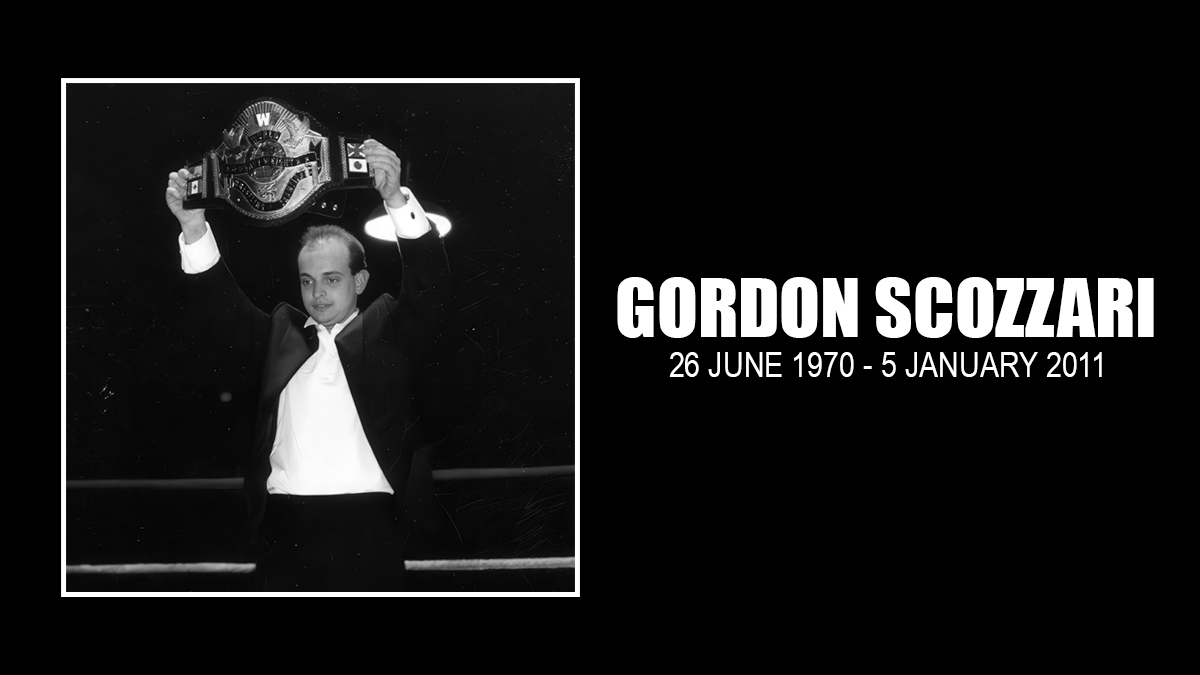

In 1991, 21-year-old Gordon Scozzari began running shows under the banner of the American Wrestling Federation (AWF). For Scozzari, wrestling should have provided him with worth, purpose, and escape. Instead, the business consumed him until his last days, leaving only myths, controversies, endless tragedies, and unrecognized achievements behind.

Scozzari’s story reveals the ruthless dog-eat-dog side of wrestling. It’s a business that can sniff out the vulnerable and dispose of them, which is seemingly justified by the thinking, “If they don’t know how to protect themselves then they deserve it.” As fans continue to open new promotions, Scozzari’s tale is as relevant today as it was decades ago.

Scozzari was born on June 26, 1970. His family was originally from England but later moved to the United States where they settled in the Brooklyn/Queens area of New York. Scozzari adored his mother, who passed down her love of British wrestling to her only child.

While Scozzari enjoyed watching the squared-circle brutes, his appearance couldn’t have been more different than those in the ring. He was an awkward and gawky kid.

Pro wrestler Sunny Beach (Rick Allen) remembers Scozzari well.

“I thought he was a loner. He didn’t have too many friends. He was a little eccentric. I don’t want anyone to take this the wrong way, but he was a little nerdy, skinny,” Beach says. “He wasn’t a sissy, but he wasn’t a tough kid. He was a gentle soul.”

Scozzari wasn’t the casual fan who would occasionally watch WWF Prime Time Wrestling. He craved more. Born with an insatiable curiosity, Scozzari dug into the inner-goings on of the sport by reading newsletters and trading tapes with other fans across the country.

The newsletters sometimes ran reader pages where fans could connect with other diehards.

One of those diehards was Mike Henry, who met Scozzari through a mutual friend named Evan Ginzburg. Henry was the co-promoter of Northeast Wrestling. He became one of Scozzari’s best friends.

“It was like a conglomerate of friends here in New York. It was Mike Johnson [of PWInsider], Evan Ginzburg, and a few other people,” Henry recalls. “I’m further upstate. So, I didn’t get a chance to see them as often as I did. But we talked all the time. And so, it was kind of like a mutual-admiration society for newsletter people back in the day.”

Scozzari also began to befriend insiders such as Beach.

“Gordy used to come to some of our shows, independent shows, in Brooklyn and around Staten Island and stuff. He lived in Brooklyn, downtown Brooklyn, and he’d come to those shows and he’d hang out, then he’d pick my brain and we became friends,” Beach remembers.

Still, Scozzari wanted a bigger presence in wrestling and it was at a time when he could realistically achieve it. It was early 1990s. Most of the regional territories had closed, and independent promotions, some run by fans with no real experience, were taking their place.

Scozzari realized this. He regularly attended independent shows at New York’s Penta Hotel, which were run by a wrestling newcomer named Herb Abrams. If Abrams could do it, Scozzari knew that he could do it, too – but better. He had a broader knowledge of the wrestling landscape than Abrams did, and he didn’t have the personal demons that haunted Abrams.

It was still a large risk, which Beach knew from running his own independent shows.

“I tried to tell him not to do it at first. I said, ‘Save your money. That’s a wrestler’s business. You’re going to lose all your money,’” Beach recalls.

In what would become a reoccurring theme, Scozzari insisted on going forth with the AWF despite the warning. Although he wished that Scozzari would wait, Beach still gave his time to the fledgling promoter.

“I spent a lot of time with him. He would come to my house in Brooklyn almost two, three times a week before he was booking the show and picked my brain and I gave him phone numbers of guys to talk to. I did a lot of stuff for the guy and, believe me, I didn’t take his money like everybody else did,” Beach says.

Scozzari could run a wrestling promotion, but whether or not he could run it efficiently was unclear. In an industry populated with larger-than-life roughnecks flexing massive chests and 24-inch pythons, Scozzari’s sickly, rail-thin physique couldn’t command the attention nor the respect that a burly, baritone-barking leader like Bill Watts or Fritz Von Erich could.

To complicate matters further, Scozzari didn’t just look ill. He was ill.

“His health issues during the AWF times were bad,” Henry says. “He had kidney disease. And he was taking medication for that, and he was trying to control it. But he didn’t really take good care of himself with that.”

Despite being fully aware of the uphill battle ahead of him, Scozzari wouldn’t back down. He knew struggle. He knew disappointment. And by the time he was 21, he knew tragedy. Both of his parents passed away from cancer less than a year apart. The life that Scozzari knew was over, but his new life had yet to start.

While the death of his mother left an emptiness in him that wouldn’t subside, Scozzari still had a lifetime in front of him. He had to fill the void. He had to start the AWF.

He’d bankroll the AWF himself. He had the cash, which itself has been a source of mystery and speculation. The rumor, which has been reported by newsletters like The Pro Wrestling Torch, is that the money came from his parents’ inheritance, but his parents were modest librarians. There wasn’t a huge nest egg waiting for him.

There have been other explanations. On the WrestlingClassics message board in 2007, Scozzari wrote that the money for the AWF came from stocks and a share of profits from a company merger. The truth might be somewhere in the middle.

“He had ventured stock options from his parents, because he had an inheritance. And a lot of that was basically stocks. He also put a lot of money away,” Henry says.

Scozzari had an unwavering vision for his AWF, and no one, not even his closest friends, could persuade him otherwise. It didn’t matter how much evidence or logic there was to the contrary, such as when Ginzburg asked why Scozzari planned to run the first show on December 14, 1991, in Asbury Park, New Jersey.

Ginzburg is the creator of the newsletter, Wrestling – Then and Now. He was also the associate producer of the films The Wrestler and 350 Days.

“I’m going, ‘Gordon, Gordon, this is a summer resort town. It’s bitter cold there in the winter. The transportation is lousy. Nobody’s there in the winter, okay?’” Ginzburg remembers. “‘Gordon, wait, at least wait till the summer.’ I said, ‘This is not the place to go in the dead of winter.’ He was consumed by it. You couldn’t talk to him.”

Scozzari needed bookers. He enlisted Beach to secure local talent, but he also had to find a matchmaker. For that job, Scozzari chose Eddie Gilbert, who was the hot booker at the time, having found success in the Continental Wrestling Federation and Bill Watts’ Universal Wrestling Federation.

Although Beach worked on finding talent, Scozzari already had ideas of his own.

“Gordon had a great thing for getting unique and independent talent,” Henry says. “He could see things that other people couldn’t see and find uniqueness in other people that they didn’t see.”

Some of those unrecognized stars included Dave Finlay, Robbie Brookside, and William Regal. However, this skill wasn’t always the most constructive when it came to determining his AWF roster.

“[Scozzari]’s furiously booking that show for months and he’s calling me, ‘I got this guy, I got that guy,’” Ginzburg explains. “I’m like, ‘Gordon, nobody knows this guy in America. The guy’s from England, nobody knows him.’ I go, ‘Yeah, TNT is big in Puerto Rico, but nobody knows him in New Jersey.’”

Scozzari wrote on WrestlingClassics that he had to rely on talent outside of the region, because Beach “had heat with every local wrestler you could dream of” which forced him to look elsewhere for talent.

Beach disagrees.

“I got a lot of friends in the wrestling businesses. If I had heat with anybody, I never knew it,” Beach says. “I mean, I’ve booked a lot of shows here in New York, for myself and for Herb [Abrams], and I was on a lot of shows with Tommy D and you name it, every promoter on the East Coast, I probably worked for at one time or another. And I don’t think I had heat with too many people. I mean, I always did my job.”

While he landed some worldwide talent, Scozzari never factored in the detriment that it could have on his budget. Wrestlers such as Hercules Ayala and Savio “TNT” Vega from Puerto Rico were solid acquisitions who could bring a Caribbean flair to the show, but some questioned whether or not their involvement on a show in the Northeastern United States would be worth the investment.

“He’s talking like an obsessed sheet reader. He wanted to book the best show possible,” Ginzburg says. “He wanted to bring in names that meant a lot to him and the hardcores and the guys that think like him.”

Scozzari claimed this was never his intention.

“My original idea/vision which I should have gone with (and would have if Sunny hadn’t made enemies all over the tri-state area) was to do small shows ala Johnny Rodz when he used to run the old Gleason’s [gym] — all locals with maybe two names. Things got out of hand. Maybe I just should have canceled, or stiffed people on pay then I would have fit in nicely with all the other scumbag promoters I was being compared to,” Scozzari wrote on WrestlingClassics.

Most of the wrestlers Scozzari chose were actually located in the United States. These included marquee names like Stan Lane, Paul Orndorff, Nikolai Volkoff, Bob Orton Jr., Manny Fernandez, Adrian Street, and the Junkyard Dog. He also chose some of the best up-and-comers like Chris Candido and Sabu.

Scozzari didn’t skimp on their payouts, or anyone’s payouts, for that matter.

“I don’t think anybody taught him what a pay scale of what an actual independent wrestler is,” Henry says. “I think he paid them as if he thought he was going to be Vince McMahon.”

“He was spending money a lot. All the people really wanted from Gordon was his money, to be brutally honest,” Beach says.

That’s when the news made its way around.

“In the wrestling business, if you’re a novice, and you’re new, the guys, when they find out that you’re willing to pay an exorbitant amount of money for talent, then they tell other people,” Henry says.

In a business where promoters wield almost all the power, Scozzari wanted to be the anti-promoter. He wanted to be fair and reasonable. It didn’t work. The wrestlers took advantage of his people-pleasing naivety, gouging him for every last dime.

On December 1, 1991, Scozzari appeared on John Arezzi’s wrestling radio program. He sounded hopeful as he listed several matches for the Asbury Park event. These included Paul Orndorff vs. Nikita Koloff, Hercules Ayala vs. TNT, Kamala vs. Norman in an explosion match, the Sheik and Sabu vs. Ron Garvin and the Cheetah Kid, Eddie Gilbert and the Dirty White Boy vs. Sunny Beach and Jeff Gaylord, and Robert Gibson and Jeff Jarrett vs. Bob Orton and Barry Horowitz. None of those matches would take place.

On the night of December 14, 1991, these aforementioned factors turned the heavily planned Asbury Park event into chaos. This wasn’t just because the wrestlers didn’t accept Scozzari as an authority figure, but also because the original booker, Gilbert, no-showed the event despite already getting paid.

“Eddie had good intentions and he was going to be there,” Henry remembers. “But Eddie was scatterbrained and double booked himself. That’s just as simple as that.”

Scozzari needed to find a booker quickly. With much of the talent looking out only for themselves, Savio Vega, Dutch Mantell, and Pez Whatley helped to restore order.

Gilbert wasn’t the only absence. Ron Garvin, Jeff Jarrett, Robert Gibson, Tom Prichard, Cheetah Kid, Steve Williams, Tim Horner, Jim Cornette, Stan Lane and Dan Spivey were also absent from the arena. The Sheik was scheduled to wrestle, but the New Jersey State Athletic Control Board hadn’t cleared him. Angelo Poffo was set to perform the ring announcing, but he left early and Scozzari had to take over the reins.

Then there was Nikita Koloff.

“Gordon thought that it was a coup to get Nikita on the show because Nikita hadn’t been on TV [in a while], and he thought that he would work,” Henry says. “But Nikita couldn’t work. So, he paid him a whole lot of cash for nothing, just to come in and cut promos, to lead to something with him and Orndorff down the line. But Nikita really didn’t do anything for him. And I know that pissed him off.”

On WrestlingClassics, Scozzari acknowledged that Koloff couldn’t wrestle, but he didn’t harbor any resentment towards the faux-Russian. According to Scozzari, Koloff “developed a hernia a week before the show” but “brought him in anyway to counter all the changes and no-shows.”

Orndorff and Koloff never had their program. They both moved on to bigger paychecks when the opportunities arose.

The Wrestling Observer reported that the show drew 275 fans. Scozzari never publicly confirmed nor denied the number, although he did write that 475 fans actually paid. A winter storm may have played a part in ticket-holders choosing to stay at home.

To make matters worse, the Asbury Park show was intended to be taped but the cameras never arrived.

The novice promoter had another shot, however.

On December 16, 1991, Scozzari ran a television taping in Lowell, Massachusetts. While an estimated 1,600 tickets were sold, only around 450 fans attended the show due to a blizzard. The AWF had another chance, but it quickly turned into a repeat of Asbury Park.

For the Lowell event, Scozzari spared no expense for the taping. He recruited the experienced crew who worked on International World Class Championship’s television. He invested heavily in the production, arranging for a four-camera shoot with one camera attached to a crane. Pyrotechnics were also on display in an attempt to differentiate it from every other independent show. In all, the production cost $22,000.

The Lowell show was centered around a one-night tournament to determine an AWF World Champion. The finals saw Paul Orndorff win the title by defeating Stan Lane. Recognizable names in other bouts included Sabu, Kimala, Adrian Street, Junkyard Dog, Bob Orton, Barry Horowitz, Nikolai Volkoff, Manny Fernandez, Chris Candido, and Hercules Ayala.

Some of the talent on the Asbury Park show were scheduled to appear on the Lowell taping. However, Scozzari paid them with one check for both days and a few of the wrestlers didn’t bother to show up for the second show.

With the second AWF event descending into madness, Scozzari lashed out.

“He kind of blamed me for all his misfortunes,” Beach says. “And I was like, ‘I don’t know what’s going on with this.’ And I felt terrible about him losing all his money, but he did it to himself.”

The troubles continued after the event. Orndorff kept the AWF World Championship belt, explaining that he needed it for a video game commercial that he and Hulk Hogan were shooting. Orndorff never returned it. The whereabouts of the belt are unknown to this day.

Controversy followed the promotion everywhere. In one of AWF’s most infamous scandals, Scozzari allegedly paid Jeff Gaylord $5,000 to beat up Gilbert at the Dallas Sportatorium during a Global Wrestling Federation taping as revenge for Gilbert skipping the AWF events.

Scozzari’s responded by writing on WrestlingClassics that “the only reason I ended up connected to their fight (which was really over Eddie not using Jeff when Jeff was late to four shows in a row) is the fact that Jeff, who I and Savio Vega (Juan Rivera) fired when we were taping extra footage in [Puerto Rico] for wrestling under the influence of pot, was Jeff’s decision to wear an AWF T-shirt when he did it.”

In an interview with Highspots Wrestling Network, Gaylord claimed that Scozzari did pay him to rough up Gilbert. However, he says that he and Gilbert agreed to stage the fight and split the money afterwards. Also included in the fight was Gilbert’s brother, Doug Gilbert, who assisted his sibling.

It was also rumored that Scozzari was visiting the Junkyard Dog backstage at a WCW event when Madusa (Debrah Miceli), who was Gilbert’s wife at the time, confronted Scozzari as payback for the incident involving Gaylord.

“This is how crazy that story gets,” Henry says. “Originally, I got told the story happened somewhere in Massachusetts or Maine. And I said to Eddie, I was like, ‘Did it happen in Dallas?’ And he goes, ‘Oh, that story took on a life of its own.’ He says, ‘I can’t even remember anymore. I was screwed up during those Dallas tapings.’”

Gilbert didn’t even know where the supposed fight took place.

“And I said to him, ‘Do you even remember what happened?’ And he goes, ‘Well, I remember what happened, and Doug [Gilbert], and Madusa kicking Jeff in the head,’” Henry says. “And I’m like, ‘Yeah, but did it happen in Dallas, or did it happen in Worcester, or did it happen in Maine?’ ‘Michael, I don’t even remember wrestling in Worcester and Maine unless it was for Vince. Jeff Gaylord was probably still in diapers then.’”

Madusa herself didn’t deny an incident with Scozzari, but doesn’t remember much about it, beyond pushing and shoving.

None of this kept Scozzari away from the wrestling business. According to Scozzari, he ran 10 shows after the AWF events, most of which he said made a profit. Oddly enough, he co-promoted with Beach on a show in Staten Island, despite the animosity Scozzari felt for him. Never one to pass up an opportunity to be in the industry, Scozzari even worked as a ring announcer for IWCCW.

Then Scozzari endured another tragedy. His fiancée died (though no one interviewed could recall her name). The mental strain caused him to quit promoting. It just wasn’t worth it anymore.

“That was a car accident,” Henry remembers. “And they’d just gotten engaged. And that’s the one that, besides losing the money, is the one thing that he never wanted to talk about. The money thing, he knew that I knew. And I said to him, ‘Look, you can tell me. I’m not going to run to anybody and tell them anything. Do you need anything? You need any money? Are you okay?’ And he said he was okay. He said, ‘If I needed anything, I’ll ask.’ And he would get pissed off.”

It devastated Scozzari. The stress got to him.

“He would yell at me, and then curse me out, and hang up the phone,” Henry says. “He had a tendency to do that. But then once he cooled down, he knew that I was only looking out for him, and then he would call me back and apologize. He would apologize quite quickly. There wasn’t a time where he and I really ever would hate each other.”

While the AWF event had been a disorderly mess, the multi-camera footage looked impressive. If he had any chance to save the AWF, it’d have to be by selling the show into syndication. That never happened, so Scozzari continued to wait for a break that would never come.

Scozzari’s luck looked to have changed when he became the booker for Gloria Uribe’s AWF promotion in Puerto Rico. Although the initials remained the same, the name was altered slightly from the American Wrestling Federation to America’s Wrestling Federation. Scozzari kept the lineage of his tag title, but ignored his World Championship, and brought in the belt-holders Jeff Gaylord and Sunny Beach. They lost the championship soon after to Jose Estrada Sr. and Jose Estrada Jr. who were then defeated by Bruno Sassi and Dan Ackerman.

This felt different to Scozzari. Things were looking up.

Henry visited Scozzari in Puerto Rico for two weeks.

“He was living on the beach in Isla Verde. At the time, I think it was the happiest he ever was because he thought he was going to put that AWF fiasco behind him,” Henry says.

It just fit. Scozzari loved Puerto Rican wrestling.

“Gordon, like everybody else back in the day, read the magazines, and used to look at the pictures in the back of Wrestling World magazine in Puerto Rico with the blood and the gore. And that’s what he was fascinated by, and he wanted to do the same exact thing since he was a horror-movie freak,” Henry says.

It seemed like the he was finally achieving the success that had eluded him all his life. Scozzari hoped to land a television deal in the United States for the Puerto Rican AWF and subsequently run shows in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and up through Maine.

A promotional battle erupted in Puerto Rico between the AWF and Carlos Colon’s World Wrestling Council with the AWF signing WWC’s Chicky Starr, Hercules Ayala, and Hugo Savinovich. It was the right time for the AWF to strike. The WWC was still reeling from the backlash that followed the murder of Bruiser Brody in 1988.

When the AWF landed a television deal with a Spanish-speaking channel in New York, the promotion’s future looked promising.

“The thing about Puerto Rico is that when they really go to war, in a promotional war, it’s really a promotional war. You could be threatened at any time down there,” Henry says.

Not everything was perfect. The plan to bring the AWF stateside proved to be harder than originally thought since some of the talent didn’t have visas. In addition, Scorazzi didn’t believe Gloria Uribe, the promoter of the AWF, was holding up her end of the deal by supplying wrestlers for the events. Then the television deal fell apart when Uribe failed to send in tapes along with the payments to the station for the shows to run.

The stress continued. His kidneys were still an issue. The health care in Puerto Rico couldn’t properly treat Scozzari’s condition. He left the Caribbean behind and returned to the United States where he slipped back into his job as a legal librarian.

Scozzari didn’t stay in the United States. In 2001, he left the bad memories behind him and moved to England where he ran a pub/restaurant. He mostly avoided the wrestling business, but occasionally worked for Welsh promoter Orig Williams as well as Hammerlock UK and promoter Andre Baker.

“He went back over, because his aunt was over there,” Henry says. “So, he found some place reasonable to live, which wasn’t as expensive as living in New York City. And he found out that, with his kidney issues, they weren’t as well equipped to take good care of him as much as New York was.”

In 2007, after spending years away from wresting, Scozzari responded to fans and critics on the message boards at WrestlingClassics. His health was worsening. He was going broke. Now he once again found himself consumed by wrestling.

“He would respond to everybody that had complaints about him back in the day,” Henry says. “And I told him, ‘That’s not healthy for you. You can’t argue with everybody because not everybody’s going to understand, because a lot of those people are novices and marks, and they don’t understand.’ And they really got under his skin. And he resented everything. And even though I tried to tell him, “Hey, you can’t read all this stuff. It would make you sick and make you go crazy.’ And eventually, it really did.”

Scozzari was resentful. He felt cursed. He lost his parents at an early age. He lost his fiancée. He lost his money. He lost his dream of running a successful promotion. He lost his life in Puerto Rico. He lost his thriving restaurant. Then he lost the function of both of his kidneys.

“Gordon was living in Times Square in a squatter hotel because he couldn’t afford anything else, basically. And so, his health was deteriorating,” Henry remembers. “Gordon was going to dialysis three to four times a week. And I would talk to him every day, like five times a day.”

Even up to his death, Scozzari still thought about putting on shows. He couldn’t quit. No matter how badly the business treated him, he couldn’t turn off his ideas and thoughts.

“He would have lineup sheets of shows he was booking, at least in his head, that never materialized on scraps of paper. ‘I’m going to bring in this guy and I’m going to bring in that guy,’” Ginzburg says.

Scozzari was emotionally wounded. He lived his life through a filter of inevitable disappointment.

“One time, WWE booked a show on the same day as one of his proposed shows that never materialized and he says to me, ‘They’re trying to f*** me,’” Ginzburg remembers. “I’m thinking to myself, ‘That’s crossing a line into obsession, delusion, whatever.’ It basically made him miserable and destroyed his life. With that being said, I never quite knew what was real and what wasn’t real between him and the obsessive fans. You never really knew.”

Although Scozzari and Ginzburg were friends, they still had their share of disagreements. Ginzburg suggested that Scozzari may not be cut out for the wrestling business. An argument followed. Scozzari told him to “Drop dead,” with a religious slur. They didn’t speak for years. However, an encounter at an independent wrestling event reconciled the friendship.

“I would visit him all the time. Why? Because it was just the right thing to do,” Ginzburg says. “It was the decent thing to do. One time he says to me, he goes, ‘You are my best friend.’ I never thought of him like this. I mean, I know a lot of people and I have a best friend going back 40 plus years from when I was a kid. That’s the way he was. Either you could do no wrong, or you could do no right. If he didn’t like you, it was almost obsessive. He hated the sheet people; he hated the website people.”

On January 5, 2011, Scozzari passed away at the age of 40. He went to the hospital on New Year’s Day and never left.

“I was Gordon’s emergency contact,” Henry says. “If anything was to happen, if something were to happen to Gordon, I was his last emergency contact. And the way I found out that Gordon passed away is because Gordon’s social worker, who I kept in contact, called me and said that the doctors were trying to get a hold of me because I was listed on Gordon’s do not resuscitate list.”

This came as a surprise to Henry.

“He actually never told me that I was his power-of-attorney,” Henry remembers. “Only thing he told me was, ‘If you don’t hear from me, and somebody calls you, and you’re the only person that I have that I trust, could you make the decisions for me?’ And I was like, ‘Are you sure about that? I mean, is that legal?’ And he says, ‘Well, I really don’t have anybody else that could do it for me.’ And I was the only person left to trust in, besides Evan, who were local.”

Scozzari didn’t rest peacefully.

“It was a memorial at the hotel where he died and I was the only person from the wrestling community, period,” Ginzburg says. “It was pretty pitiful, the whole thing. There was a lot of mentally ill and drug addicts and such, and not that I’m being derogatory, I’m just stating a fact.”

Henry did not attend the memorial service due to being ill at the time.

“There was a sign on the wall that advertised Gordon’s memorial that emphasized free refreshments, so I’m assuming some of these people there didn’t even know him,” Ginzburg says. “They were there for the free refreshments.”

No one was certain what should be done with the body.

“So, they asked me, ‘What am I supposed to do with his body?’ Because nobody knew what to do,” Henry says. “His parents were buried somewhere, I think, in Brooklyn. And his girlfriend was buried in Brooklyn because that’s where they all grew up. But since I actually wasn’t a member of the family, I couldn’t make those arrangements. I had to call his aunt and tell her that he died, and that she was going to have to make the arrangements through the social worker to take care of his remains.”

Henry never knew what happened to the body. After giving Scozzari’s aunt the news about her nephew’s death, he never heard about it again.

“[Scozzari] really deserved a whole lot better than what he got at the end,” Henry says. “And I really loved him to death. He was really a good guy. He was hard to deal with sometimes, misunderstood. But I understood what he was going through. I just tried to help him as best as I could. And we never hated each other. We may have fought every once in a while, but there was no hate at all. Nobody would make you their power-of-attorney in the end if they really hated you.”

There is still a fascination with Scozzari and the AWF. Ginzburg’s upcoming book, Wrestling Rings, Blackboards & Movie Sets, contains a heartfelt essay on his former friend. And the AWF footage will be officially released by the Savoldi Family Wrestling Library on a streaming service specializing in classic footage called the Savmar Wrestling Network.

Scozzari didn’t have the physical intensity of a Bill Watts, but he didn’t need it to prove his resiliency and toughness. He continued to chase his dream after all the setbacks. He lived two years longer than the doctors thought he would.

In the end, Scozzari lasted longer in wrestling than anyone would have thought and he lasted longer on this world than anyone would have thought.