In the 1950s, Hollywood was focused upon big genre blockbusters, with astronomical budgets shot in exotic locales, and where directing and acting took a back seat to set design and costuming. At the end of that decade, a group of filmmakers in France revolted against this style, and took film back to its basics: with stories based on real life, shot in real places, and with shaky, hand-held cameras. The French New Wave, as they came to be known, made films for a fraction of the budget of Hollywood blockbusters, but they changed the world of cinema forever.

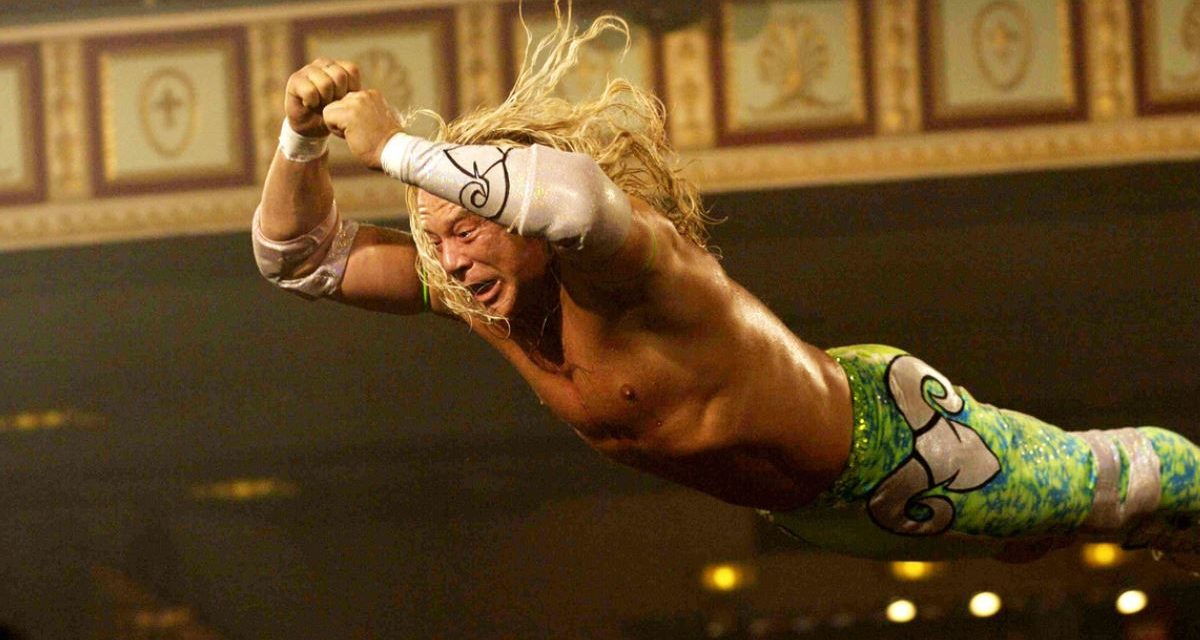

- Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler

Fifty years later, after a summer dominated by expensive genre films created by computer programmers and special effects maestros, like The Incredible Hulk and The Dark Knight, an American filmmaker has rejected this excessive style: Darren Aronofsky has made a loud statement with his film The Wrestler, just as Godard did in 1959. The power of the film, screened at the Toronto International Film Festival, is in its simplicity: while other modern films start with explosions or costumed crimefighters, this one begins by showing us what appears to be a young, jacked-up muscle man from behind, sitting on a chair. But when the camera spins around to show us his face, we are shocked to see that it is wrinkled and tired. And there begins the story of Randy “The Ram” Robinson, a wrestler in his 50s with a roided-up body to make him seem like he’s 30. It is the story of a man who has a choice between living in the illusory world of wrestling and living in the real world — or to use wrestling terminology, between living a “work” or a “shoot” — and the constant struggle he has between those two worlds.

The Ram comes to life thanks to the brilliant performance by veteran actor Mickey Rourke. Rourke actually gets in the ring and executes a number of very difficult wrestling maneuvers, including an off-the top turnbuckle head-scissors takedown. A former boxer, Rourke decided to train as a wrestler for this film, going to the school of wrestling legend Wild Samoan Afa’s wrestling school in Pennsylvania for a number of months. As anyone who has ever survived Afa’s wrestling school will tell you, it is like going to hell and back, if your body can withstand the punishment. Rourke did not wish to be an armchair critic of the pain that wrestlers must endure: he experienced it first hand, spending a few nights in the hospital due to injuries sustained during his wrestling training. Add to this Rourke’s own mastery of playing outsiders and anti-heroes, and you have nothing less than an Oscar-worthy performance. If he is denied it, then the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is as fixed as a pro wrestling match; they have a choice this year of rewarding Rourke, who battled his own demons and ultimately defeated them to engage in one of the greatest performances ever seen in American cinema, or the overrated Heath Ledger from an overhyped CGI film wearing clown makeup who decided to throw in the towel against his demons and take the easy way out.

Also memorable in roles are Ernest “The Cat” Miller, who appears in the film only briefly, but steals every scene he’s in, calling into question the wisdom of wrestling owners who banished him from their shows; and Dylan Keith Summers, known to the most hardcore of wrestling fans as “The Necro Butcher.” As much as Beyond the Mat immortalized Mick Foley, The Wrestler has instantly immortalized The Necro Butcher, an American wrestler whose style involves him doing real damage to his body in the ring, like having his opponents really fire staples into his skin via a staple gun. Some film critics thought that he was invented for the film — they couldn’t believe that he was for real. Because of his vicious style, none of the mainstream wrestling companies have hired him to date, and he might have only been remembered by the most hardcore of wrestling fans, were it not for The Wrestler. It is ironic that it is Hollywood that has given him the credit he so rightly deserves. Fans of wrestling will also recognize many other cameo appearances from stars of Ring of Honor and Combat Zone Wrestling. It pays tribute to them, their athleticism, their fraternity, and the tenderness they show to their fans. Long dismissed by the mainstream media and Hollywood, The Wrestler recognizes that they are real American heroes. Wrestlers are not monsters here.

Amidst these three fantastic portrayals, one might think that Marisa Tomei might be overshadowed, but her role as a stripper and love interest of The Ram is powerfully portrayed. Tomei does the impossible: she takes the role that would have easily been interpreted as something seedy and questionable, and turns it into a role of a female savior. It is no accident that her character praises The Passion of the Christ to the Ram, as Tomei makes her role akin to Mary Magdalene.

At the same time, this film is not a Ready to Rumble lovefest. Screenwriter Robert Siegel deserves much credit for writing The Wrestler, leading to it becoming the best film ever made about professional wrestling. His script also calls into question some of the risks wrestlers take in terms of their physical well being, and the low payoffs they receive from promoters in return for sacrificing their health for them. Researching even the phenomenon of wrestling conventions, in one of the film’s most touching scenes, we see old wrestlers sitting at tables hawking their 30-year-old t-shirts and photos of them in their youth. No one visits their tables, and they sit alone in wheelchairs, falling asleep, with wrestling fans flocking to younger wrestlers instead. We see The Ram at his table, still remembered by some fans, who buy his merchandise, while the older wrestlers look on sadly, like dogs at the pound begging to be picked up before being put to sleep. The film then cuts to The Ram, his eyes looking at them as a harbinger of his own future.

No film’s component parts can shine unless a master auteur is at the helm, and Aronofsky reveals himself to be worthy of that title. He has not abandoned the visionary power witnessed in Pi and The Fountain: he is as uncompromising as ever, and that takes The Wrestler beyond the category of a merely great film to that of an “Instant Classic,” to quote TNA wrestler Christian Cage’s catchphrase. It takes a while for the rest of the world to catch up with the wisdom of a genius, and it his critics that have had to eat crow and finally appreciate his filmmaking style. Aronofsky deserves an Oscar for his direction.

He inoculates the film with a passion and energy that makes it awe-inspiring without allowing it to be held hostage by CGI. Everything about this film is real. His camera does the talking and shows us the world through The Ram’s eyes. One of these brilliant visual touches occurs when The Ram retires from the world of wrestling to take a job as a butcher in a grocery store. On his first day, Aronofsky’s camera tracks him from the grocery dressing room through the long corridors of the warehouse, until he finally steps through the curtains to appear in front of the public; the exact same shot is shown earlier in the film when The Ram is walking to the ring. The Ram is doomed to see the world only through wrestling terms.

Other than his visual style, Aronofsky’s most important tool at his disposal in this film is his choice of music. It opens with the rousing ’80s Quiet Riot metal anthem, “Metal Health,” which becomes the theme music of The Ram. Other ’80s heavy metal classics, like “Balls to the Walls,” are also played in the film, mostly used as theme music for the wrestlers, reminiscent of Paul Heyman’s use of loud, alternative music for his wrestlers in the original incarnation of ECW. After all that loud music, Aronofsky ends the film with the quiet, elegiac song The Wrestler, written and performed by Bruce Springsteen, specifically for the film.

Evan Rachel Wood and Mickey Rourke.

While a work of cinematic art, Aronofsky makes no bones about his intent to also make it a film about social change. His film celebrates the artistry and humanity of professional wrestlers, but it in no uncertain terms condemns the way they are cast aside by wealthy wrestling company owners. The Wrestler is The Grapes of Wrath meets Raging Bull. In fact, this film will be spoken of in the same breath as Raging Bull. The Ram is a broken man, who lives on the edge of poverty, and who has sacrificed everything for his professional wrestling masters, including his family and friends. But professional wrestling has given him nothing in return but misery and a dying heart. At an age when other sports heroes are comfortably retired, he has to continue to put his body and health on the line. Aronofsky draws attention to this lifestyle in all of its horrible brutality. In this way, his film is much like the late, great John Huston’s film exposing the evils of the boxing profession, Fat City, and just as dark: we see wrestlers juicing, we see them taking somas, we see them taking painkillers, we see them taking cocaine, we see them with bags of drugs that would make a pusher jealous.

Like a French New Wave film, the tone of this film is not meant to be a happy one. The Ram chooses to ignore the reality of his situation and overstay his welcome in the imagined world of piledrivers and dropkicks. His daughter (Evan Rachel Wood), his girlfriend, and a medical doctor try to steer him off that path. But The Ram opts for oblivion over salvation. And the sad thing is that this is not simple fiction. There are many Rams in the world of professional wrestling, and unfortunately they outnumber The Rocks. While some would have us forget who they are and erase their existence from their shows and official histories, The Wrestler tells their stories, and forces the world to pay attention to them. This is not a romanticized Chariots of Fire, but instead, to quote Alan Moore, about men who are “Chariots of Wrath, by demons driven.”

THE WRESTLER (2008) LINKS

-

- June 17, 2009: The Wrestler still resonates with Ring of Honor

- May 23, 2009: The Wrestler ‘really got to me’: Piper

- Feb. 23, 2009: Analysis: Rourke’s predictable loss at the Oscars

- Jan. 20, 2009: Associate Producer of The Wrestler documents wrestling’s killing fields

- Sep. 17, 2008: Aronofsky and Rourke passionate about The Wrestler — and wrestling