Writing about the wrestling days of Emile Dupre, who died on September 17, 2023, at the age of 86, was fairly straightforward.

Writing about his days as an assistant promoter to Cowboy Len Hughes and then running his own promotion in the Canadian Maritimes for 20 years is not so straightforward.

There’s backstabbing between promoters, cries of cheapness, accusations of being behind the times — which could be in almost any territory.

But there’s also success, a lot of it, and with it comes jealousy.

The key to the promoting days of Emile Goguen lay in the fact that, as Emile Dupre, he truly paid attention as he traveled the globe to wrestle. He made friends, didn’t burn bridges, and could call in favors.

He once summed up his thoughts on professional wrestling as such:

There’s an old saying, “When you’re in this business, you’ve got to win the dressing room.” If the guys are starting to dislike you, or something like that — there’s always some; I always found if you could win the dressing room with the guys, it’s like a team, and that’s how you wind up doing good in this business. I’ve seen guys, cocky-type of guys, and some of the guys start to dislike them, and they don’t do too well, I’ll tell you that.

Perhaps it’s a simplistic take, one that didn’t necessarily age well, but it was his vision.

So was this: “I quickly learned the most important thing in this business was the bottom line.”

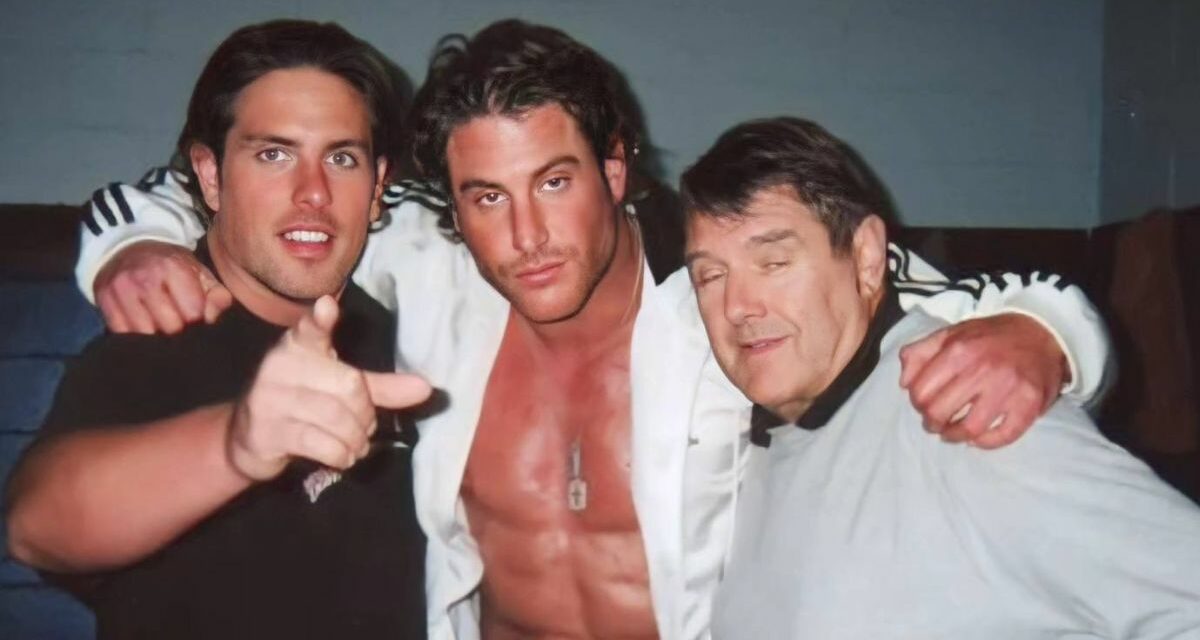

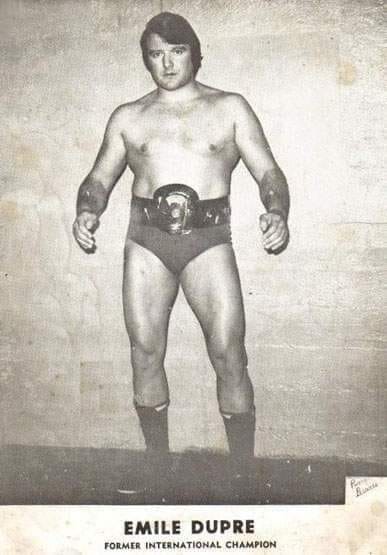

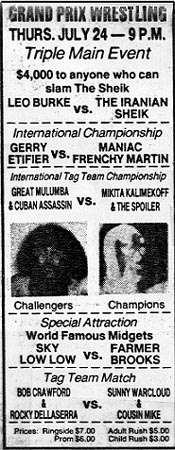

An Emile Dupre promotional photo.

To truly understand the appeal of wrestling in the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, you have to think summer. Beaches. Fishing. Fresh seafood. Relatively short drives to shows. Small towns without a lot of other attractions, vacationers looking for something to do. Regulars who went to all the matches. Festivals, and rings set up in a farmer’s field for a celebration of all things potatoes. The Halifax Forum, the biggest venue in Atlantic Canada at the time, was built in 1927 and could seat about 7,000 for pro wrestling.

NWA World champion Harley Race, in a SlamWrestling.net interview, once addressed a tour of the Maritimes: “Truthfully, the week I enjoyed up there was very enjoyable. I met a lot of great people and ate a lot of lobster. If I had the opportunity to go back, I’d go back.”

And Goguen was a homer, he loved to come home himself for the summers when he could. “I wanted to be in the Maritimes in the summertime. I didn’t want to be anywhere else no matter how good I did,” Goguen said. “I left San Francisco, I left Charlotte, North Carolina. They said, ‘Why, you’re doing great?’ I said, ‘I know, but I want to go home.’ They didn’t understand that. When a wrestler was doing real good, why would he want to take off? My thing is that I was going to wrestle, but from June to September, I was home. That was the deal, no matter how good I did.”

He kept in touch with old friends. Despite not finishing high school, he was financially savvy, having listened to friends. He once talked about the life lessons he absorbed:

I had friends. When I started working out with the weights, they went to university and became professors at Moncton University. One guy became my accountant that I used to work out with when I was a kid. He was quite good in business. Sometimes we’d have a coffee and talk about different kinds of stuff. He was interested in real estate. He was the first guy to say, “Look,” as he started poking around, “in wrestling, how are you doing? How are you making out? Do you get to save a little bit of money?”

I said, “I’m not a millionaire or anything like that, but I did save a few dollars.”

He said, “I’d advise you, for maybe a pension or retirement kind of stuff, invest in real estate.” It was a small investment. He said, “Try it out,” which I did.

Holy crap, that was the best move I ever made in my life. It was a rental, it was a duplex. I was only 20 years old. I learned right quick. My problem was that I wasn’t here, so I had to have somebody take care of it. How it worked out, the real estate agent, the guy who sold me the place, just said, “Look, we’ll take care of it. We’ll collect the money and see that it’s rented. We’ll charge you a small fee. When you come back in the spring or summer, we’ll have all the receipts.” Jesus Christ, I wasn’t there. They had something to put in the bank.

They said, “Look, we have another building we’d like you to see.” Exactly the same thing. It was a three-unit apartment. Then it went from there, until I owned as much as 65 units. Buildings I bought years ago, one in particular, I paid $82,000, and 14 years later, I sold it for over $200,000. The building had paid itself three times. So there you go. As a matter of fact, I made more money with real estate than I did with wrestling. …

If it hadn’t been for wrestling, it would never have happened, it would never have happened. I had no college education or anything like that, let’s not forget. I was just going on a shoestring.

With that mentality at Goguen’s very core, he saw pro wrestling as a means to an end, a way to further his slowly-growing empire.

He wasn’t shy about asking questions, observing how things worked behind the scenes in pro wrestling. Two key figures were Johnny Doyle and Jim Barnett, who were co-promoters in Detroit, Indianapolis and Australia at various times, and ran territories on their own too. Dupre learned a ton from Barnett, especially. “I just had to observe what was going on. I learned from him is right. I became a promoter in a smaller way, but everything I knew about promoting wrestling, I learned from them, him and Johnny Doyle. I had a lot of respect for both of them.”

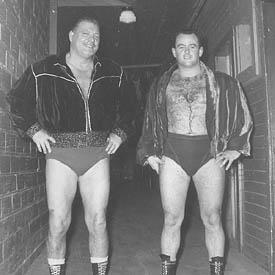

Cowboy Len Hughes and Bud Cody in London, Ontario, in the 1950s. Terry Dart Collection

Back in the Maritimes, Goguen had already worked for Len Hughes, who was an American who married a woman from Halifax, and settled in as a promoter after his wrestling days had ended. Hughes was getting older and Goguen stepped up to help, circa 1964. It was an apprenticeship … until it wasn’t.

After a stint in the United States Navy during World War II, Hughes got involved in the promotional end of things in the Maritimes, partnering with Clary Harris and Alvin Brown, who owned a furniture store in Halifax. Harris and Brown also promoted boxing.

“Len Hughes was the one that knew all about wrestling, but these guys had the money,” recalled Goguen. “They were three partners running the business, they were the investors. I want to tell you, they did great, until Clary Harris got cancer and passed away. The other guy, Brown, was strictly the bookman. When that happened, he wasn’t interested. I was wrestling in those days.”

Goguen did invest with Hughes, becoming a partner. Eventually there was a falling out, and, like any good wrestling promoter story, there are many questions about who betrayed who. In one take, as told by Al Zinck, another Maritimes promoter, Goguen started booking arenas on his own, without Hughes, leading to the separation.

Goguen’s take was different.

“To make a long story short, I invested money with Len Hughes,” said Goguen. “Another guy invested too. The thing was dead, then all of a sudden it started booming. We brought in [Whipper Billy] Watson and Gene Kiniski. I remember being on my knees to bring the little midget girls. He said, ‘Why would people want to see that?’ He couldn’t understand that. We brought them in and drew $7,000 in those days with the small prices, $7,000 in Halifax. Moncton was $4,000, where we had been drawing $1,000, $1,200. He said, ‘I don’t understand, how come that can draw?’ I said, ‘That’s attractions that they’ve never seen before.’ He couldn’t see through that. He had lost it. The business went great until the end of the summer. I was getting paid like a wrestler. At the end of the summer, when it came time to settle up for my investment — I hadn’t put in a million dollars, I had only put in $5,000 in the deal. In the middle of the summer, he gives me my $5,000 back. Now he had a cushion, he’d made money. At the very end of the season, I asked, ‘What did I get for my investment?’ He sat down with a bunch of papers and showed what all the expenses were. He settled up and I had made some money. ‘But,’ he said, ‘that was for one season only. It isn’t for next year.’ Now that the thing was on fire, it wasn’t for next year. It was morally wrong, but business-wise it was good, which is okay, that’s fine. It seemed to me that when a guy invests, he should be included next year now that the ball is rolling. He said, ‘Maybe that’s your point of view, but that’s not mine.’ I said, ‘Okay, that’s fine.’ That’s when I became a promoter, right there and then. That was his downfall. I put him out of business.”

Hughes continued to run the next year: “He didn’t do good, though. I’m going to tell you the truth — I didn’t do that shit hot either! But what happened was I got myself involved in dealing with the different arenas. I started learning what I could do, and the people I could get. After that, I tried again. It was no million dollars coming in, it was still barely living, still barely surviving. But it got me in as a promoter, and that’s the story of my life right there.”

Not widely known was the fact that Goguen brought in Don Leo Jonathan (Don Heaton) as a partner in what would become Atlantic Grand Prix Wrestling for a few years, though was initially International Wrestling.

“He was in Newfoundland and he was in the diving business. But I knew him long before that. I first met him in Boston and the Forum in Montreal in my early days,” recalled Goguen. “I was just about the close the territory. I had a wrestling bear, and I was just about the close. He called me up and said, ‘I’m on my way through from Newfoundland next week. Do you have anything going?’ I said, ‘Geez.’ He was an attraction. He had been on television from Vancouver, All-Star Wrestling. … I said, ‘Look, give me a phone number.’ I got on the phone and I started calling different towns and telling them they could have Don Leo Jonathan.’ … I said, ‘I’ll tell you what, after all the card is paid, all the expenses is paid, whatever is left, we split 50-50.’ He said, ‘Wow, that sounds like a fairly good deal.’ And I didn’t realize at the time, but it was a hell of a deal — for him and for me. I drew more opening the territory for six weeks, than I had in the whole summer. I said to Don Leo, ‘Look, would you be interested in coming back here next year, on the same kind of deal?’ ‘Yeah.’ So he brought his wife, his kids in here for the whole summer. He was here two, three summers. It worked out real good for me. Naturally, we got Andre the Giant, Edouard Carpentier was here; he was the guy wrestling them.”

The Andre the Giant story was often-told by Goguen. “When I brought in Andre the Giant as a promoter, we’re talking about profit. I made as much money in 10 days that I had or put away in my first 10 years of wrestling.” The reported amount was $40,000 in one telling, $100,000 in another.

Things and dates get confusing. For a time, Goguen didn’t promote, and Eastern Sports Association, which was the promotion run by Rudy Kay and Al Zinck in the Maritimes, was the main show in town, roughly from 1969 to 1976. Since so many of the same talent were used first by Goguen and ESA, it is easy to combine it all into one continuous promotion — but that is not the case.

In 1977, Goguen finally landed a television deal on his, which ran for a decade. ESA had been competition for a time, but now it was gone.

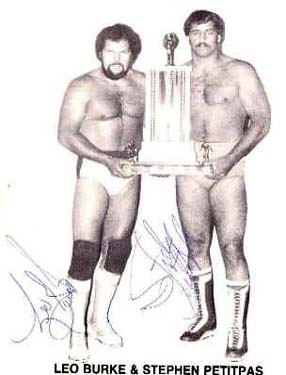

It was the beginning of a magic time, said Leo Burke, who had worked with his brother, Rudy Kay. “After Emile Dupre took over, I was away maybe three years. I was in Charlotte, North Carolina. I was fed up and wanted to come back home, so I gave Emile a call. I did tremendous business again for Emile for seven, eight years. In fact, it was so successful, he was running two groups.”

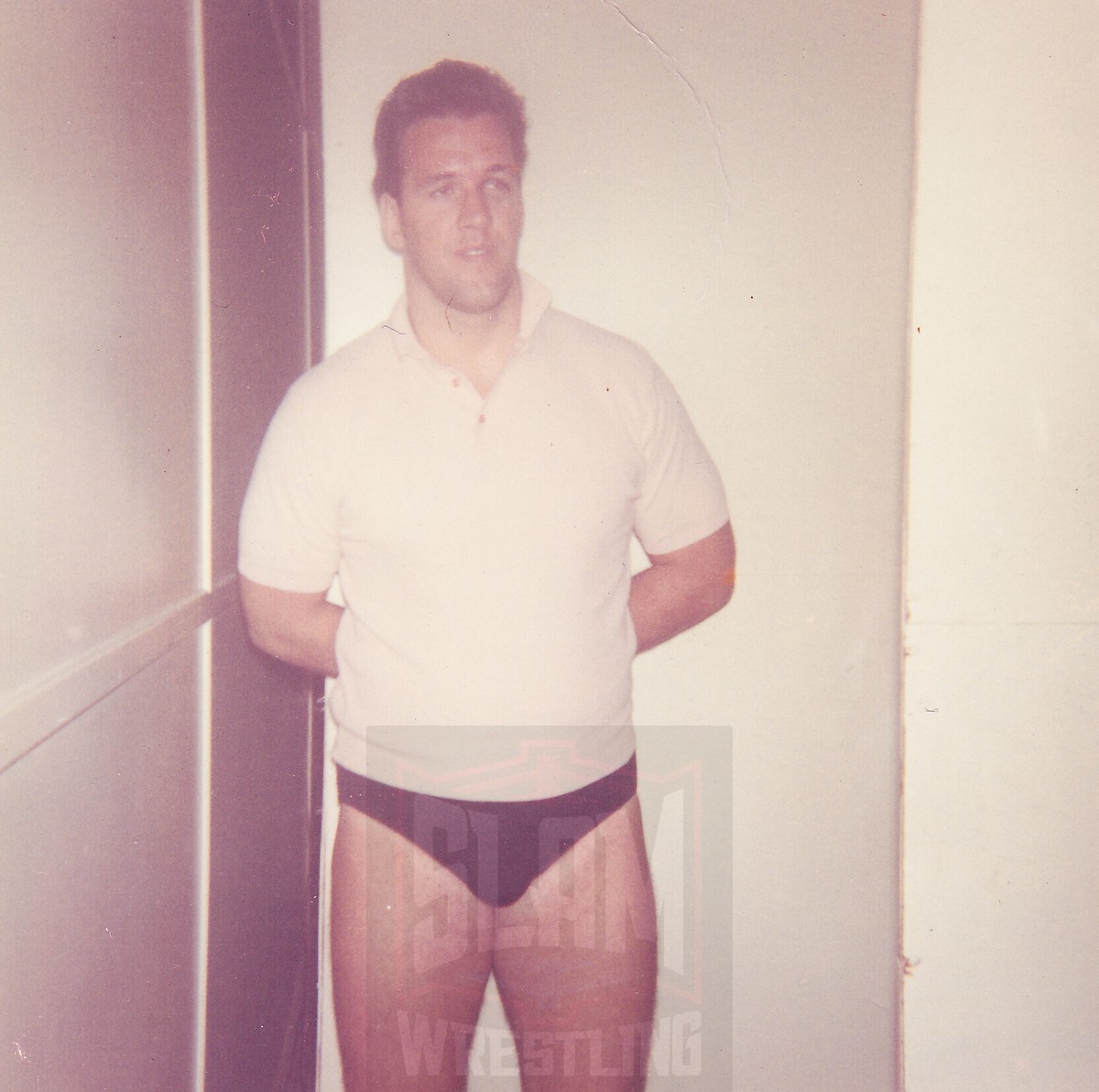

Leo Burke and Stephen Petitpas

Indeed, Atlantic Grand Prix ran shows on the same night during the heart of the summer. By the time the promotion was closing down for the season, usually around early October, near Canadian Thanksgiving, it was single shows. “That’s how I used to run things. I used to run 14 shows a week, I had two groups,” said Goguen. “I had two rings, three rings, really, two rings, two trucks, two vans.”

Goguen once explained the merchandise table and the importance of 8×10 photos — always of the heroes — at his shows. “It would cover the cost of the truck, motels, and setting up the ring. I want to tell you, I used to sell as much as $2-3,000 a week. My brother [Ron] was in charge of that,” he said, adding cagily, “It was just prints, and the government doesn’t know how much you sold.”

The success of the shows wasn’t consistent, and history has a way of glorifying in retrospect. But the TV shows of ESA and then AGPW were truly ingrained into the memory of wrestling fans in the Maritimes. It was Killer Karl Krupp calling Bill McCullough “MrMcCluckCluck!” The antics of “No Class” Bobby Bass and Goldie Rogers. The stylings of Sweet Daddy Siki. The heroics of Leo Burke. “Rotten” Ron Starr breaking a bottle over his head. The untrustworthy Cuban Assassin.

Thursday nights at the Halifax Forum were key, said “No Class” Bobby Bass. “We made him a lot of money, I don’t care what anybody says. Me, Leo, Frenchy [Martin], all the guys there who worked the main events. His big house was on a Thursday night in Halifax. That paid for everything, and everything else was all gravy. He was the first guy that I knew that ever said, ‘Bring me the money!'”

It was more than just the big arena, of course. “When we got the TV and all that, we could have had a wrestling match in a hayfield somewhere and draw a crowd. It was good. For me, it worked out great,” said Goguen.

Don Jardine — the future Spoiler — in Halifax, August 1964.

Atlantic Grand Prix was also young, up and comers. Often overlooked through Goguen’s days as a wrestler and then a promoter was his influence on younger talent. There was a young Don Jardine, years away from headlining as The Spoiler, or his neighbor Stephen Pettipas befriending Goguen and learning the trade. Likely any talent from the 1960s onward that came out of the Maritimes owes Goguen a debt of gratitude.

A wrestling ring would be set up on Goguen’s property in Shediac. “I don’t run a wrestling school,” Goguen once said. “If I talk to you and think you have potential, I’d train you and not charge you. … Maybe to get a couple of guys with fat bellies hanging out saying, ‘Hey, I want to collect a couple of thousand of dollars from you, show you a couple of dozen holds and send you home,’ I’m not going to do that.”

Goguen was always on the lookout for talent. “I was in Shediac, and I used to work in dance halls,” recalled “Stompin'” Paul Peller. “We had a sea-side arena there. Emile Dupre in Shediac, he had started out and he asked me if I was interested. I wasn’t very interested because I didn’t know anything about it.” But Peller did train and wrestled for two decades.

Through the years, Japanese talent came in too, like Masahiro Chono as Tokyo Chono, Junji Hirata as Sunny War Cloud, or a young Seiya Sanada in 2015.

The later generation, even when Goguen didn’t have television, benefitted too.

Robert Maillet, who wrestled in WWF as Kurrgan, was trained by Goguen disciple Petitpas, and then got a chance to wrestle for AGPW for a summer. “It was a thrill of a lifetime,” Maillet said of being in the ring. “My first big opportunity, my dream really, that I had been thinking about since I was a kid, a teenager, was wrestling. Working for Emile Dupre, Grand Prix Wrestling I watched for years. I was a big fan of it, and all of a sudden you’re in the ring with your heroes. It was a big thrill, and I remember that summer very, very well.”

Ron Hutchison was one of the few who worked both eras of Goguen, as the Masked Thunderbolt. “I spent six summers touring for Emile Dupre, working 7 nights a week for months on end working with some of the best names in the business. It was a learning experience like no other and one I’ve, publicly, been thankful to Emile for since the very beginning,” Hutchison posted to Facebook.

Ron Hutchison and Emile Dupre. Facebook photo

Dick Durning posted a note of condolence after Goguen’s death: “Rest easy Emile Dupree, if it wasn’t for u taking a chance on a rugged kid from North End Saint John NB I wouldn’t be who I am today.”

“I have nothing but mad respect and appreciation for Emile,” Kowboy Mike Hughes — named by Goguen after Cowboy Len Hughes — told SlamWrestling.net. “Always have always will. He changed my life and gave me opportunity to see the world.”

“Hercules” Peter Smith, who later became Kingman, started his career with Goguen. “Emile was my first promoter. Although we had our disagreements in later years, I always held him in the highest regard and always will. I’ll never forget the lessons he passed down or his passion for pro wrestling.”

It was the desire of Goguen’s son, Rene, to become a pro wrestler, that got Emile back into promoting summer wrestling in 1997, offering one of the few places in the world at the time that would allow talent to work night after night. His other son, Jeff, would wrestle too, but was nowhere near as successful as Rene.

A whole new generation would not only get a chance to wrestle, but, with the growth of the internet and the general deregulation of pro wrestling and the smoothing out of the playing field meant that there would be promotions vying for the same arenas and venues. Real Action Wrestling was one, and there were countless others.

“In this territory here, I know my onions,” Goguen once said cryptically in a story about all the competition.

It became an annual tradition where Goguen would get in touch with SlamWrestling.net and spread the world about where he’d be putting on shows in the summer.

There were plenty of different criticisms for Goguen’s promoting.

He changed wrestlers’ established names on a whim. He duplicated names that were in other promotions. He played fast and loose with copyright. Some felt he held down local talent in favor of the bigger names that were paid more and came from afar.

“He was pretty fair with the guys. He wanted to change my name, I remember, to Bad Mad Dog Bass, and I said no,” recalled Bass, who wrestled and managed for Goguen.

There was a cheapness, though, added Bass. One time, Goguen came into the hotel room Bass [Dennis Baldock] was sharing with his wife, Helen, and praised Bass for drawing so well with Cuban Assassin. “Now, don’t tell nobody — I’ll give you a couple of extra bucks,” said Goguen. Bass picks up the story: “He whipped out a roll of money that could choke a horse. He had a hundred in his hand. I looked at Helen, she looked at me, and we looked at that hundred dollar bill, and the next one was a fifty. He pulled out the fifty and put the hundred back in the roll. He left, then we roared.”

In the end, no wrestler is ever happy with a promoter.

But there’s a legacy, concluded Hutchison. “Emile Dupre was an often overlooked Canadian pro-wrestling icon. He gave work and opportunities to so many of us with his Grand Prix Wrestling territory. A grand territory that just might have been the best kept secret in pro wrestling.”

TOP PHOTO: Jeff, Rene and Emile Dupre. Facebook photo

RELATED LINKS