Danny Hodge was the rarest of individuals who inspired universal awe and admiration across the combat sports spectrum.

In American amateur circles, he was without peer, and already an icon by the time he retired. Before his name was ensconced on the Hodge Trophy, synonymous with the highest level of achievement in American amateur collegiate wrestling, those who faced him on the mat already realized that they were, at best, competing for second place.

For professionals who faced public skepticism around the legitimacy of their craft in an era where the business had to be protected, Hodge was always “the realest man in the room,” and someone who could be pointed to as affirmation for the toughness of the professional business.

For figures involved in the contemporary efforts to revive catch-as-catch-can wrestling as a legitimate art, Hodge, who died on December 24, 2020 at 88, was considered one of the art’s last great figureheads following the passing of Lou Thesz, Karl Gotch, Billy Robinson, and Billy Wicks.

For pioneer athletes involved in the fledgling “shoot” and MMA movements of the 1990s, Hodge was a source of both inspiration and speculation around “what might have been.”

Above all, however, Hodge was a towering figure of kindness and humility to all who knew him.

Hodge’s rugged upbringing in Perry, Oklahoma, as vividly described by Steven Johnson in his recent article for SlamWrestling.net, forged him into a mentally indomitable athlete who would never back down from a fight.

That attitude, coupled with freakish physical strength and technical wrestling prowess, catapulted him to the top of the amateur ranks.

By the 1950s, Oklahoma was one of the great national hotbeds for amateur wrestling in the United States, and Hodge, who wrestled for the Oklahoma University Sooner squad, was the state’s undisputed star.

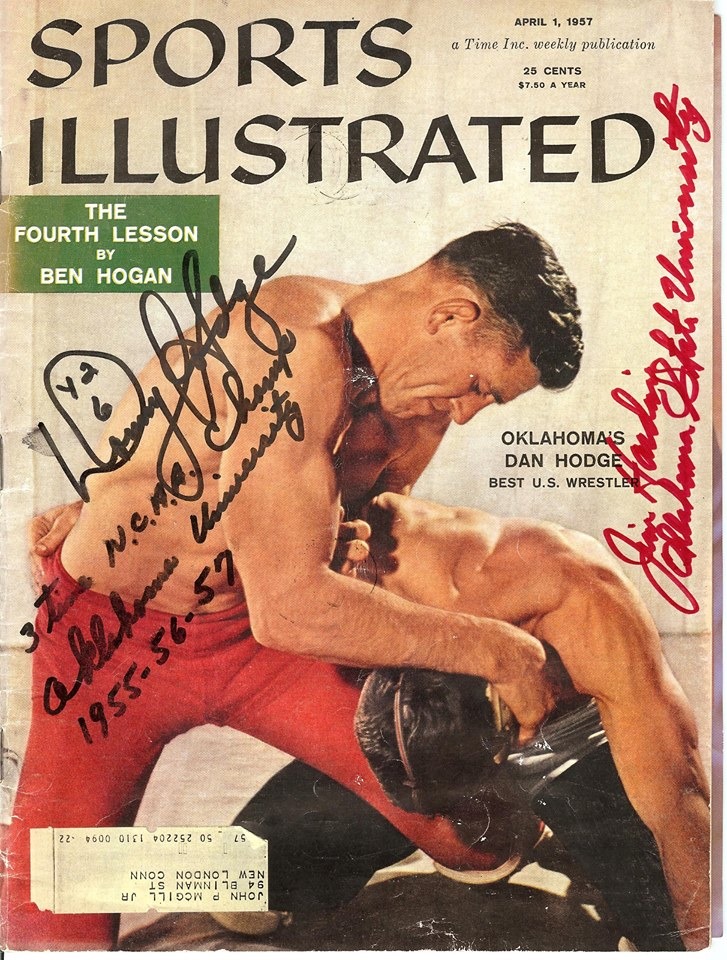

Perhaps the only Sports Illustrated signed by both Danny Hodge and Jim Harding. Courtesy Steve Nelson

Jim Harding, who wrestled for the rival Oklahoma A&M (by 1957, Oklahoma State University) recalled that, as a freshman, he ended up standing next to Hodge at a tournament. “Hodge was right beside me, and I looked at him and he was impressive… He would demand your attention just to look at him.”

As his amateur career proceeded, Harding would have an even closer encounter with the famed son of Perry—and not just on the cover of the April 5, 1957 issue of Sports Illustrated, where Hodge is tying up an unnamed wrestler—Harding—making the pair the only amateur wrestlers ever on the cover.

During the 1950s, NCAA wrestling was contested in weight brackets, between 137 and 177 pounds, that were separated by 10 pound intervals. In 1956, Oklahoma A&M had a deep talent pool at 157 and 167 pounds, so it was not possible, according to Harding, to make the team at those weights. However, when the time came for a state dual meet with Oklahoma University, opportunity knocked in the 177 pound division.

Two brothers who were in the 177 pound weight slot at Oklahoma A&M decided they didn’t want to wrestle for a spot on the team, only to face the certain defeat that would result from a match with Hodge. Harding, however, much to their astonishment, decided to take the chance.

As Harding recalled, one of them said, “Do you really want to wrestle that big son of a bitch?” Harding was game, they replied, “Well, you go right ahead. We’re not even going to rank this week.”

Harding figured that a quick takedown could score him a point because Hodge wouldn’t expect it. Against Hodge, who was never taken down in his collegiate career, it was bad strategy, and any hopes of executing it immediately evaporated.

“When it came time for the match, it was a large crowd, it was at Oklahoma State, and when he grabbed my wrist, I thought the blood was going to spurt out the end of my fingers. It was unbelievable,” said Harding. “The thought of doing anything was just out of the question. It was probably one of his quicker pins, and fortunately for me he got it over with.”

Harding was wrestling out of his weight, but even when Hodge met men his own size, it really didn’t matter.

Mixed martial arts star Matt Hughes, the legendary amateur wrestler and coach Dan Gable and Danny Hodge in July 2013. Photo by Joyce Paustian

In 1957, Hodge faced off in a match against Gary Kurdelmeier at Iowa University. Kurdelmeier was incredibly well built and had an impressive list of accolades behind him, including winning two Iowa state high school wrestling titles in the heavyweight division, and the 1957 Big Ten title at 177 pounds. Harding, who made the trip to Iowa, thought, “We’re finally going to see some competition.”

He was wrong.

“There was absolutely no competition. [Hodge] just sort of toyed and played with him for a few minutes then just pinned him,” recalled Harding. “And Kurdelmeier jumped up and he was mad, and I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, don’t make this worse for you than it has to be!’”

Kurdelmeier went on to win the 177 pound NCAA championship one year later (defeating the future “Mr. Wrestling” Tim Woods in the finals). By then, of course, Hodge had graduated.

Even when wrestling far beyond his weight limit, elite wrestlers proved to be putty in the hands of the man with perhaps the strongest hands in wrestling history.

One such individual was Gordon Roesler.

Roesler was the NCAA heavyweight champion in the unlimited class in 1956, and placed third and second in the 1957 and 1958 championships, respectively. He was the best of the big men on Oklahoma mats at that time. Harding recalled, “He was about 6 foot 4 or 5 and he weighed 245 lbs. and he didn’t have an ounce of fat on him, and he could pick up those 300 pound guys and just throw them around.”

Every spring, Oklahoma University held a sports day that would feature a variety of athletic activities, and wrestlers from different weight categories would face one another. Despite a 60 pound weight handicap, all of it muscle, Hodge put Roesler’s shoulders to the mat.

Even into his golden years and long retired from active involvement in sports, Hodge could bring the frightening strength he used to pin the best collegiate wrestlers of his day into play when desired.

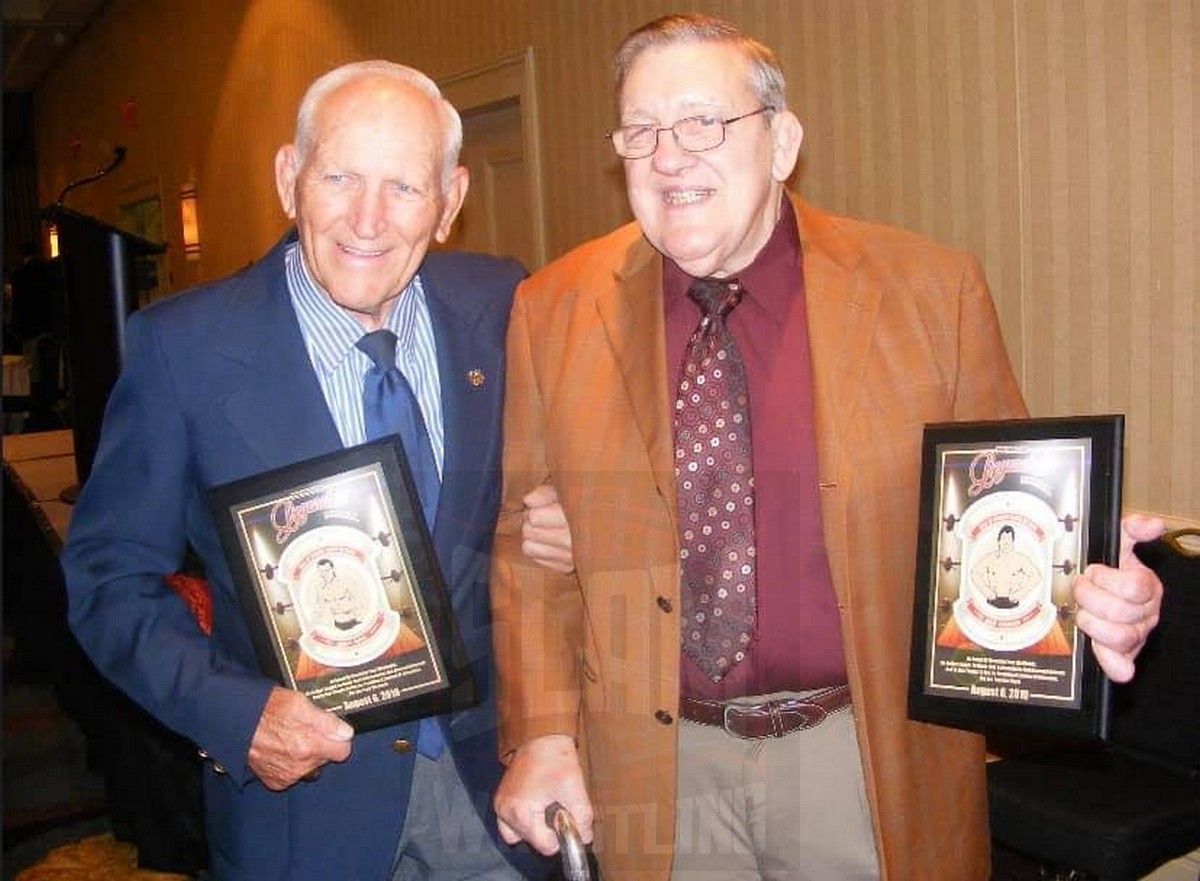

Danny Hodge and Billy Robinson in 2010. Photo by Christine Coons

During the 1990s, Hodge, along with Thesz and Robinson, were recruited by Japan’s UFWi organization to lend it credibility as it sought to challenge more established promotions such as New Japan Pro Wrestling for market dominance with their “more authentic” brand of wrestling. Talented athletes with solid amateur wrestling credentials were also enlisted, among them Gary Albright, who finished second in the unlimited weight class at the 1984 NCAAs, and Mark Fleming, who had been a wrestling standout at Norview High School in Norfolk, Virginia, and a personal protégé of Thesz.

Fleming recalled that, while staying in a hotel in Japan, he and Albright accompanied Hodge down in the elevator, where they were going to meet Thesz in the lobby. Hodge stood between the two of them and said, “Let me show you guys a type of wrist lock that nobody can really do.” Grabbing Fleming with one hand and Albright with the other, he simply pulled their wrists back and twisted.

“He had both of us on our knees, and he was laughing,” said Fleming.

When the door opened, Thesz was standing there and Hodge had both Fleming and Albright, who outweighed him by roughly 80 and 200 pounds respectively, on the floor.

Even much later, that strength persisted. NCAA wrestler and current Brazilian Jiu Jitsu competitor Johnny Buck met Hodge when he was a teenager. Buck didn’t follow sports, despite participating in them, and didn’t really know who Hodge was at the time, but the impression the Oklahoma wrestler left was unforgettable.

“His grip was insane. He had to be in his 70s when I met him,” said Buck. “When I shook his hand my eyes got real big and I looked down at his hand. It felt like wood.”

Although Hodge’s grip strength is the stuff of legend, it’s a mistake to assume that his bodily power was confined to his digital extremities. Hodge was strong all over.

Later in his life, when Ed Lewis was living in Oklahoma, he brought one of his headlock machines, which consisted of two half circles of wood separated by springs, over to the former Sooner star to see if he could close the wooden sides together. Hodge succeeded on the first try; a feat that Thesz later recalled had only been done by Lewis himself.

Fleming asserts, “It wasn’t weight lifting strength, it was tendon strength.”

As his amateur wrestling career drew to a close, Hodge embarked on a second athletic path as a boxer. In short order, he won a national golden gloves amateur championship. His professional career was short-lived, but much of that may have been due less to skill (which, given time, could have been cultivated), and more due to bad management.

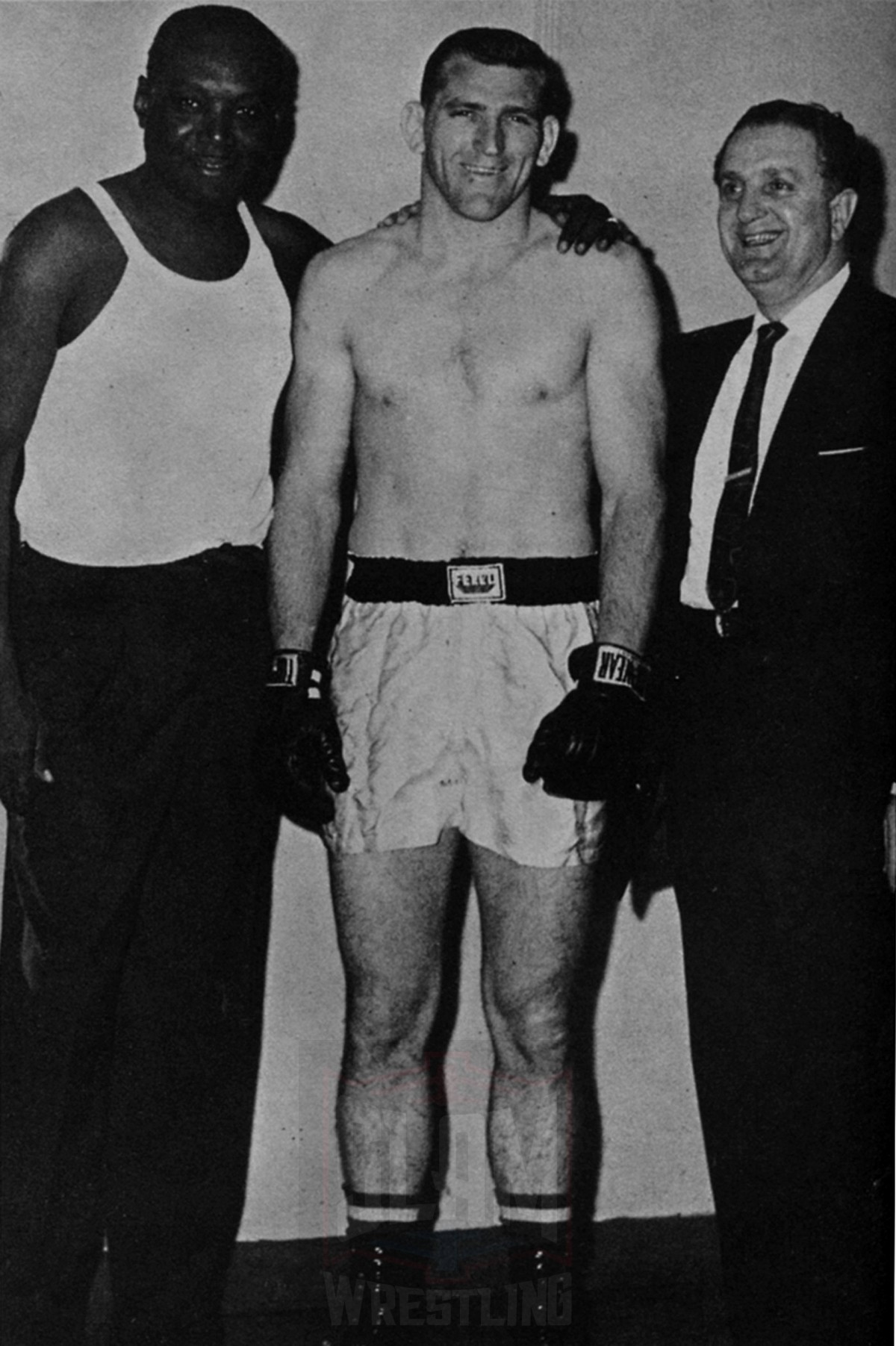

Danny Hodge, center, as a boxer. Photo courtesy Scott Teal, CrowbarPress.com

Frankie Cain, who both boxed and wrestled professionally, stated of Hodge in his autobiography, Raising Cain, “What Danny needed was a manager… a real manager to keep him in Oklahoma… He could have boxed and wrestled at the same time because he was a legitimate junior heavyweight, but his boxing career was handled half-assed.” (EDITOR’S NOTE: Slam will be posting a review of Raising Cain by Hatton soon).

With his background and ability, Hodge had the makings of the ultimate combination man, which was parlance in the fight world for someone who could make money both in boxing and wrestling. Ultimately, however, after boxing, he directed all of his energies toward professional wrestling, becoming recognized as the greatest junior heavyweight of his, or maybe any other, era.

Hodge’s presence in the professional ranks couldn’t help but boost the sport’s credibility, but he also took the business seriously, and protected its integrity, sometimes with frightening intensity.

When Ron Welch (who wrestled as Ron Fuller) began promoting wrestling in Knoxville in 1974, he sought to re-educate his Tennessee audiences, accustomed as they were to bloody brawls, with technical wrestling. To do so, he brought in both Hodge as well as Dale Lewis, who had competed in Greco-Roman in the 1956 and 1960 Olympics, and won gold at the 1959 Pan-Am Games.

Welch adopted the old carnival tactic of having his wrestlers take on challengers from the audience as a means of affirming the sport’s credibility with the public. However, he chose Lewis, and not Hodge, to wrestle the matches. Welch’s rationale was simple: Hodge was simply too dangerous. By contrast, the more mild-mannered Lewis, known for his defensive amateur wrestling style, wouldn’t hurt anyone and open the fledgling Tennessee promotion up to potential lawsuits.

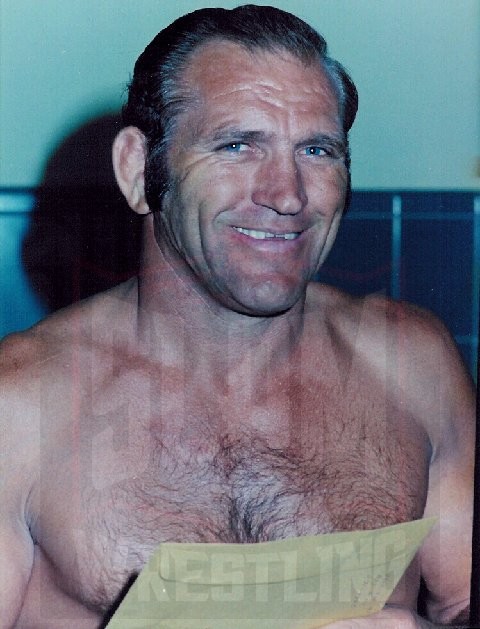

Danny Hodge, the smiling assassin? Photo by Ruth Oman, courtesy Chris Swisher.

As the weeks went on, however, Hodge appeared rankled by his fellow wrestler’s lack of aggression in the challenge matches. As Welch/Fuller related in his Stud Cast podcast, finally, when one mark began to use foul tactics, Hodge came to the ring and told Lewis that, if he did not hurt the man, Hodge was going to get into the ring and hurt Lewis! Fearing Hodge more than any other repercussion he might face, the two-time Olympian injured the mark, leading to legal troubles for Welch and both wrestlers having to make a fast exit from the territory.

As a professional, Hodge’s reputation for toughness, established when he was an amateur, ascended to new heights. Inevitably, over the years, this led to speculation among historians and pundits as to where he sits in the pantheon of all-time greats in terms of his “shooting” ability. The universal consensus puts him at, or near, the top.

In a 2012 ranking, Jonathan Snowden, author of Shooters: The Toughest Men in Professional Wrestling, put Hodge first on that list, ahead of MMA luminaries including Ken Shamrock, Brock Lesnar, and Kazushi Sakuraba. Famed broadcaster and fellow-Oklahoman Jim Ross concurs with the ranking.

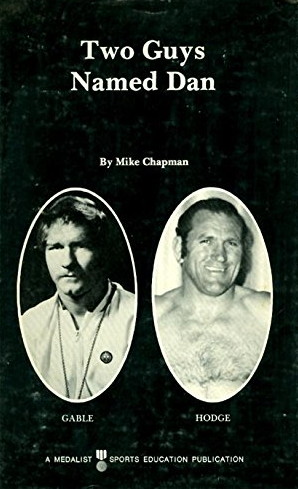

The 1976 edition of Mike Chapman’s Two Guys Named Dan.

Wrestling historian Mike Chapman, hailing from Iowa, Oklahoma’s historic rival in wrestling, permits two men to occupy the throne. “The greatest pure shoot, from what I’m hearing now, of all time, would have been [Frank] Gotch and Hodge,” said Chapman. “Just about the same size, Hodge was about 220 he tells me at his peak, Gotch was about 210 at his peak; they were about the same height.”

Because of his credentials as both a boxer and wrestler, many have also wondered how Hodge would have fared had the sport of MMA been available to him.

Jake Shannon, founder of Scientific Wrestling and a leader in the move to revitalize the art of authentic professional catch-as-catch-can wrestling, believes in Hodge. “He was, along with a handful of other professional wrestlers from his era like Karl Gotch, Billy Robinson, Gene Lebell, Lou Thesz, one of the few from that industry that not only vastly influenced the Japanese proto-MMA scene but would have dominated the sport of MMA had the opportunity been made available.”

Danny Hodge surprises Jake Shannon. Photo courtesy Jake Shannon

Legendary no holds barred fighter, Brazilian jiu jitsu black belt, catch wrestler, and MMA coach Erik Paulson, agreed. “MMA would have been perfect for him, but he was 50 years too early… If MMA was then he would have been a superstar. It’s funny because he had to box separately, he had to wrestle separately, he had to do pro wrestling separately. It was all compartmentalized.”

For others who, like Paulson, were around in the earliest days of MMA in America, Hodge was also an inspiration.

Robert Lucarelli, who fought in the second UFC and trained in catch wrestling under Robinson, stated following Hodge’s death, “He was a great example of being a well rounded fighter… Most of us will fall short as combat athletes in comparison to Danny Hodge but he inspired me and many others to be our best.”

Hodge stood as a giant in the expansive landscape of combat sports, and with his physical and mental toughness, his strength, and his skill, he had few peers. But every tribute paid to his formidable physical prowess is matched by one celebrating his kindness and humility.

Both Buck and Shannon, who knew Hodge in passing, were struck with his willingness, even in advanced years, to share his technical knowledge and training know-how.

Historian Mark Hewitt, author of Catch Wrestling: A Wild and Wooly at the Early Days of Pro Wrestling in America, recalled that, during Hodge’s induction into the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame, he “was very humble and appreciative of anyone remembering him.” Hodge also playfully traded holds with fellow ‘shooter’ and AAU Judo champ LeBell, to the delight of onlookers.

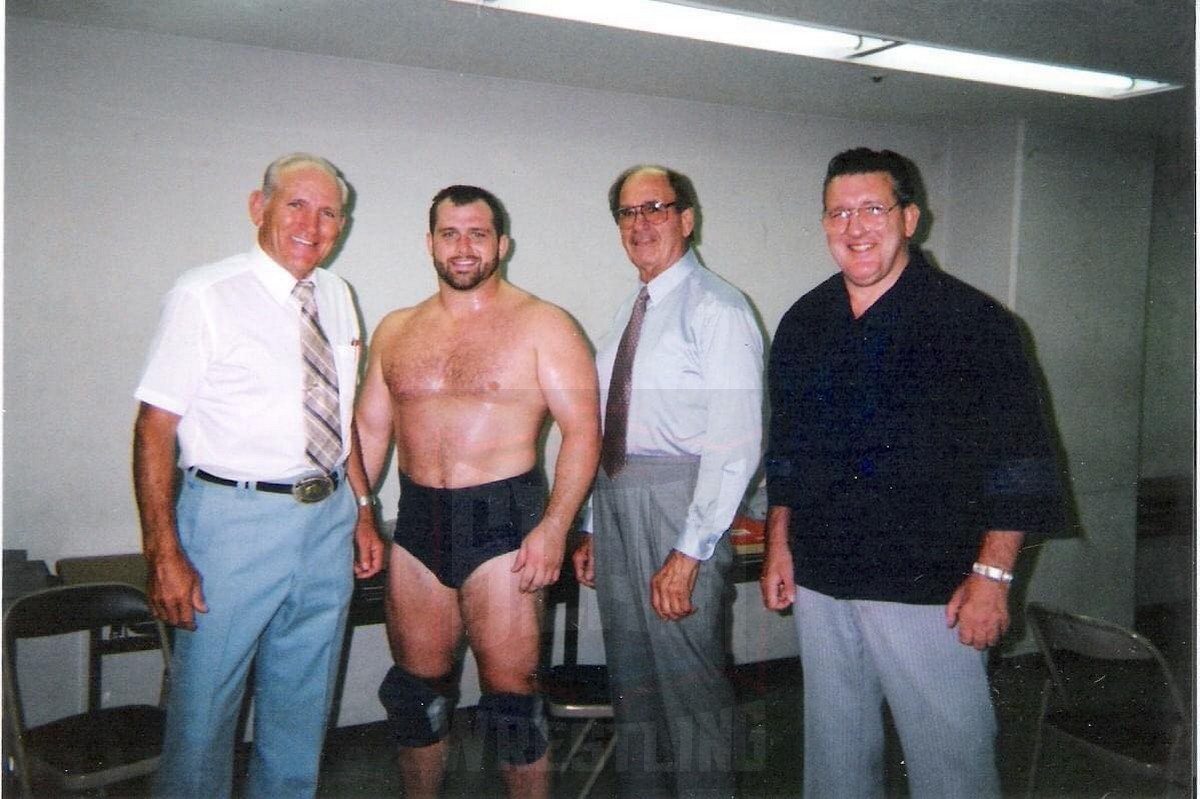

Danny Hodge, Mark Fleming, Lou Thesz and Billy Robinson in Japan. Photo courtesy Mark Fleming

Fleming, who became close with Hodge during their time in Japan, recalled how friendly Hodge was. “He was so nice. I never saw him shun a fan. He didn’t have a bad word to say about anybody. He was just so willing to help… None of us were in his class at all. And I’m talking none of us could touch him in his prime but he didn’t make you feel that way. He always treated us with respect.”

Harding reflected, “He was an amazing athlete and he was really a neat man. He was as nice as can be…. He was so down to earth and so nice. He was a real joy.”

Hodge’s legacy as one of the toughest men in wrestling will long survive him, only overshadowed by the accolades of those who remember him as one of the finest men to ever grace the mat.

RELATED LINKS