In the many times that I interviewed Danny Hodge over the years, I was always curious about how this mild-mannered, soft-spoken, God-fearing son of the American Dust Bowl could burn with the ferocity of a dozen suns.

The answer came a few years ago in a conversation we were having about Lou Thesz, the great National Wrestling Alliance champion, who Hodge adored. Speaking by phone from his living room in Perry, Okla., Hodge started to digress and tell stories, and one story shook me to the core.

It seemed as though tornado had emerged about one-half mile southwest of the claptrap house where Hodge lived. He figured he was about eight at the time. He saw the familiar tornado funnel and decided he’d like to pour water in it. Hodge went inside to tell his mother, only to be quickly grabbed with his brother and shoved into the cellar.

“I tried to look out the window,” Hodge recalled, his voice distant, “and she slapped me and I haven’t forgot that yet. I said, ‘Never do that to me again. The next one that slaps me, I’ll break your arm.’”

“A matter of respect?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “Just slapping me will be a broken arm.”

The slap always seethed. Hodge’s accomplishments are legendary, but he didn’t want to just beat you; he wanted to destroy you. “I got on the mat; I didn’t want it to go to the second period. You see what my goal was? I was a pinner and that’s what sold the crowds out.” The result: The Dan Hodge Trophy is the Heisman Trophy of amateur wrestling. To have one’s name associated with Hodge, who went 46-0 as a wrestler as a NCAA champion at the University of Oklahoma, is enough to take your breath away.

Hodge is in every wrestling hall of fame, amateur and professional, and his fabled double-tendon grip strength enabled him to break pliers and crush apples, as well as beat a generation of wrestlers.

And, for a while, boxers. Hodge boxed as an amateur after a controversial silver-medal finish in wrestling at the 1956 Olympics. He applied the same ferocious mindset to his boxing training. He ran for mile after mile, throwing imaginary punches with bricks in his hands.

“You started boxing and three minutes later, you can’t hold your hands up. The gloves get heavy. So I ran with the bricks in my hand and I guess that’s why I knocked everybody else out except one,” he said.

That would be Louis Coleman at the 1958 Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions in Chicago, which Hodge won as a heavyweight. “Out of the three minutes, I bet he didn’t throw eight punches. He was blocking. He was staggered in the corner but his kept his hands up and his elbows in and he was the only one that I didn’t knock out in all my amateur matches.”

Read that again carefully. Hodge was a national champion in wrestling and boxing. There was no such thing as UFC at the time, but there was street-fighting, and one can only delight in how Hodge might fare in the octagon. “These Air Force boys come over for Perry girls, I’d whip ’em and send ’em home. One, two, three at a time. I was in shape,” he said. “I could fight or I could wrestle and I don’t think you wanted to be on either end of it.” The 1980s athletic icon Bo Jackson may have “known” sports, but Danny Hodge knew them a long time before that.

The pro boxing career was less satisfying; he didn’t have the refined technique of lifelong boxers and ended up in a legal dispute with his management team. “I told them I can get all the fights I want here in Perry, Oklahoma, for nothing. And I don’t have to train near as hard.”

Without telling wife Dolores, always “Mama” in conversation, Hodge embarked on a pro wrestling career based in promoter Leroy McGuirk’s Oklahoma-Texas-Louisiana territory. Even as a wrestler, the slap still seethed. Asked what he thought when he got in the ring, Hodge responded with what he thought about his opponent. “You’re in shape? I don’t care what you do. I know you can’t outwrestle me and you can’t outfight me and you can’t outshape me.”

“Danny never completely got the competitor in him under control,” said Texas referee James Beard who recalled how Sputnik Monroe was hesitant to hold the NWA junior heavyweight title if it meant facing challenger Hodge.

“Sputs told me, and anyone else who’d listen, he made a lot of requests to just give Danny back the belt before he got killed trying to defend it against him,” Beard said.

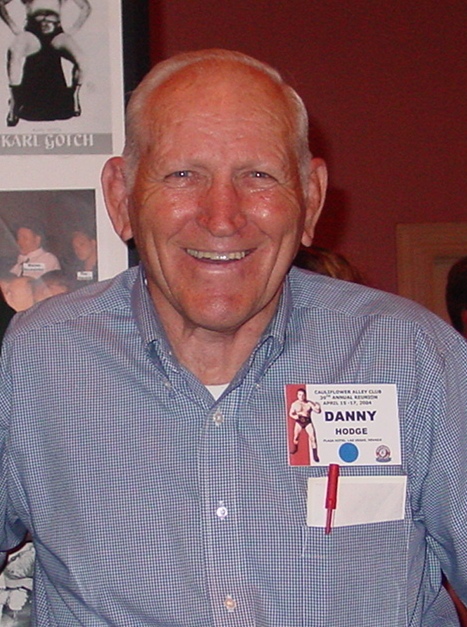

Danny Hodge at a Cauliflower Alley Club reunion. Photo by Steve Johnson

In fact, Hodge was NWA junior heavyweight champion on and off from 1960 to 1976, when injuries from an auto accident ended his career. By then, he’d been around the world 44 times, by his count.

Eventually, we wound back to Thesz in our conversation that day. Hodge had wrestled him something like a dozen times during Thesz’s final NWA title reign from 1963 to 1966, always unable to topple the champ.

In 1968, Thesz held the Trans World Wrestling Association world title, the top crown in a small Japanese promotion. To Hodge’s surprise, Thesz put him over in a Tokyo bout, though the two wrestled a strong, competitive match.

“Lou was, I’d say, fighting for his life. Can I put it more plainly like that?” Hodge asked. “The surprise was that he dropkicked me out of the ring. I got up in it, and he gave me another dropkick and then I come up and flew through the ropes and hit him in the stomach and cradled him and one, two, three. I’m shocked he didn’t kick out and the match was over.”

“We wrested numerous times in El Paso and Amarillo and New Orleans and several places. And the matches, time run out or he got disqualified. In Japan, I won. I was more shocked than anybody. It was a feeling like I never thought anything like this would ever happen. Here I am the world junior heavyweight and the heavyweight champion at the same time,” he said.

It began with a slap in a rundown house cellar and led to with thousands of fans cheering a champion. No wonder my last note from that conversation with Hodge was this:

“God’s been good to Mama and I.”

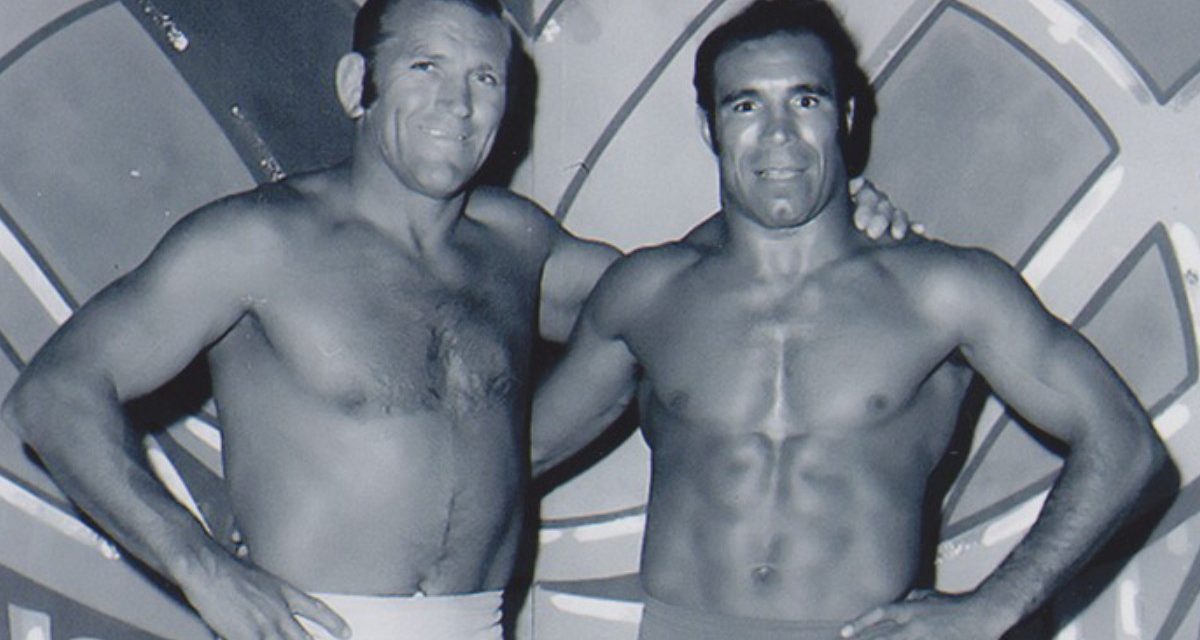

TOP PHOTO: Danny Hodge and Khosrov Vaziri — the future Iron Sheik.

RELATED LINKS

- Dec. 26, 2020: Legendary Danny Hodge dies at 88

- Danny Hodge story archive