Brian Dixon may not be a name that wrestling fans in North America know well, and Dixon’s death on May 27, 2023, didn’t get the coverage of, say, the Iron Sheik.

But Dixon meant so much to Impact Wrestling star Nick Aldis that our recent chat, arranged to talk about his upcoming challenge of Alex Shelley for the Impact World title, was derailed by Dixon talk.

It was obvious that Aldis could have kept talking for another hour about all his memories of working with Dixon and his All Star Wrestling promotion in England.

Dixon started promoting Wrestling Enterprises in Birkenhead, England, in 1970, a company that would eventually become known as All Star Wrestling. He’d already been in the wrestling business as a photographer and referee, but actually got his connections to pro wrestling by heading fan clubs, such as the Jim Breaks fan club in the 1960s. In some British magazines from that decade, he was often featured in articles presenting some of the top stars with fan-voted awards. He put in over 50 years as a promoter, with a true who’s who of international talent coming through his doors: Marty Jones, Johnny Saint, Pat Roach, Brian Maxine, “The Golden Boys” tag team comprising of Steve (William) Regal and Robbie Brookside, Tatanka, John Quinn, Satoshi Kojima, Hiromu Takahashi, Ricky Knight, Metal Maniac, Fit Finlay and Mark “Rollerball” Rocco. Perhaps the individual talent who went on to the greatest fame from an early start in All Star was “Flying” Fuji Yamada, who would become better known as Jushin “Thunder” Liger. Yamada was working for All Star to hone his craft as a young lion while on an excursion for New Japan Pro Wrestling.

Perhaps greatest achievement as a promoter was ending the grip that Joint Promotions had on the coverage of British wrestling on national television. After a significant publicity campaign, All Star was given a portion of the wrestling coverage that was showcased on ITV, as part of a revised rotation of coverage which also included the WWF. For around 30 years, Joint Promotions (a syndicate of promotions that operated like the National Wrestling Alliance in the United States) had an exclusivity agreement with the broadcaster.

What set Dixon apart was, at that time period of the 2000s, there really wasn’t anywhere else, aside from Japan, where someone could wrestle on a daily basis. This was due to Dixon’s agreement with the “holiday camps,” such as Butlins. These resorts are where families can go on vacation in the United Kingdom, which would offer a range of attractions. During the summer months, there would often be multiple wrestling shows each day, presented to a diverse audience. It was a valuable place for young wrestlers to learn their skills and ply their trade to mixed crowds, some who attended simply to heckle the talent. It also enabled the workers to learn the tricks of crowd manipulation, stemming from a “pantomime” culture that existed in the camps. It was a territory long after the territory system had died off.

Brian Dixon

“There was nowhere doing that at the time where were Brian was,” said Aldis. “I cannot stress enough how fortunate I was to get a chance to work for Brian Dixon and All Star Wrestling so, so early in my career when I really was so green and really had no business being a full-time wrestler.”

So many stories to share.

“I was training at school down near London, and Doug Williams came in, and coached for a day as a guest. He was the one who said to me, ‘You’re on the right track, you’ve got a good look, you’re a good athlete,’ that sort of thing. And he’s like, ‘You need to get some more work.’ Then Doug got me booked for a promotion where he had me booked to wrestle him. He says, ‘I’ll hold your hand through this.’ And, sure enough, he did, and carried me through a match, and everyone was happy with it,” recalled Aldis. “I appreciated even then that Doug had really done all that for me for no other reason, then he just wanted to.”

It was Williams who said: “You need to call Brian Dixon, because you’re perfect for him. He’s everything you want. But you have to call him, he doesn’t do emails, he doesn’t do texts. You have to call him on the phone.”

“The National Treasure” expanded on that point.

“This is how old school it was in that respect in that Brian was never the most tech savvy person. By the time I finished working with him, and obviously moved on to TNA and everything, by that point, he was doing emails once a week. He said, ‘I do emails on Mondays.’ He had an office in Birkenhead at a place that we called The Digs, which was like a little house, like a flophouse for wrestlers, where, particularly the international guys would stay in between the holiday camp runs and stuff,” he began. “But he also had one room in that house that was his office. So he would go in there on Mondays, because Mondays was always the off day, and that’s when he would do his emails, to check his emails, respond to them, give out dates, and that sort of thing.”

To Aldis, that structure was similar to the traditional territories.

He recounted the initial call to Dixon:

It was very strange, and I’ll never forget this, I got a number for him and they said, “Call on a Monday,” because again, that’s when you’ll actually get him on the phone because the rest of the time he’s on the road doing shows.

I called him on a Monday and I say, “Hello, Brian, my name is Nick Aldis, and Doug Williams recommended that I call you.”

“Oh, okay.”

I said, “I just wrestled Doug recently on a show for John Fremantle, and blah, blah, blah.”

Brian just cuts me off and goes, “How tall are you?”

I’m like, “I’m about 6-3, 6-4.”

And he goes, “Okay. You look good?”

And I said, “Well, I’ve got an okay physique.” I was 18 at the time, so I was in my mind, I was like, Well, I think I’ve an okay physique.

He’s like, “Well, if you’re tall and you look good, I can use you. Can you start tomorrow?”

And I’m like, “Sure.”

“Okay, come to Skegness tomorrow, be there at 12 o’clock. Pack for the week. All right, good man, see you then. Bye.”

And it’s like, pack for the week?

It was a different era. A wrestler might be able to email an 8×10, with a brief biography, and perhaps they had a grainy video available somewhere they could link to.

“When I signed on with Brian — I say signed on, I mean, there was no contracts or anything, it was just a handshake,” added Aldis.

So Aldis’ true journey in wrestling began.

A “then” and “now” set of photos Nick Aldis posted to Facebook.

“I took my gear and took everything I had, and obviously a change of clothes and stuff like that. Sure enough, he was like, ‘Right, you’re on.’ It was like that, then for pretty much that whole year, I was wrestling six days a week. Mondays off, Mondays I’d go back to my parents and do laundry and eat some real food. And then that was it, back to the grind,” said Aldis.

Looking back now, memories triggered by Dixon’s passing, he is appreciative.

“I 100% took it for granted only in the sense that I had no idea until later on, when I came to the States how there was nowhere else you could do that,” he said.

Aldis went to a Harley Race camp in Missouri, and found himself talking to the other young trainees. They all seemed to have side jobs, teaching or as an electrician, or in construction. They asked Aldis, and it was honest — he was just a wrestler.

“And they were like, ‘Wait, that’s it? How many times do you wrestle?'” he recalled. “I said, ‘Well, I worked for Dixon, so most of the time I work about six shows a week.’ And they were just like, ‘What, how is that possible?'”

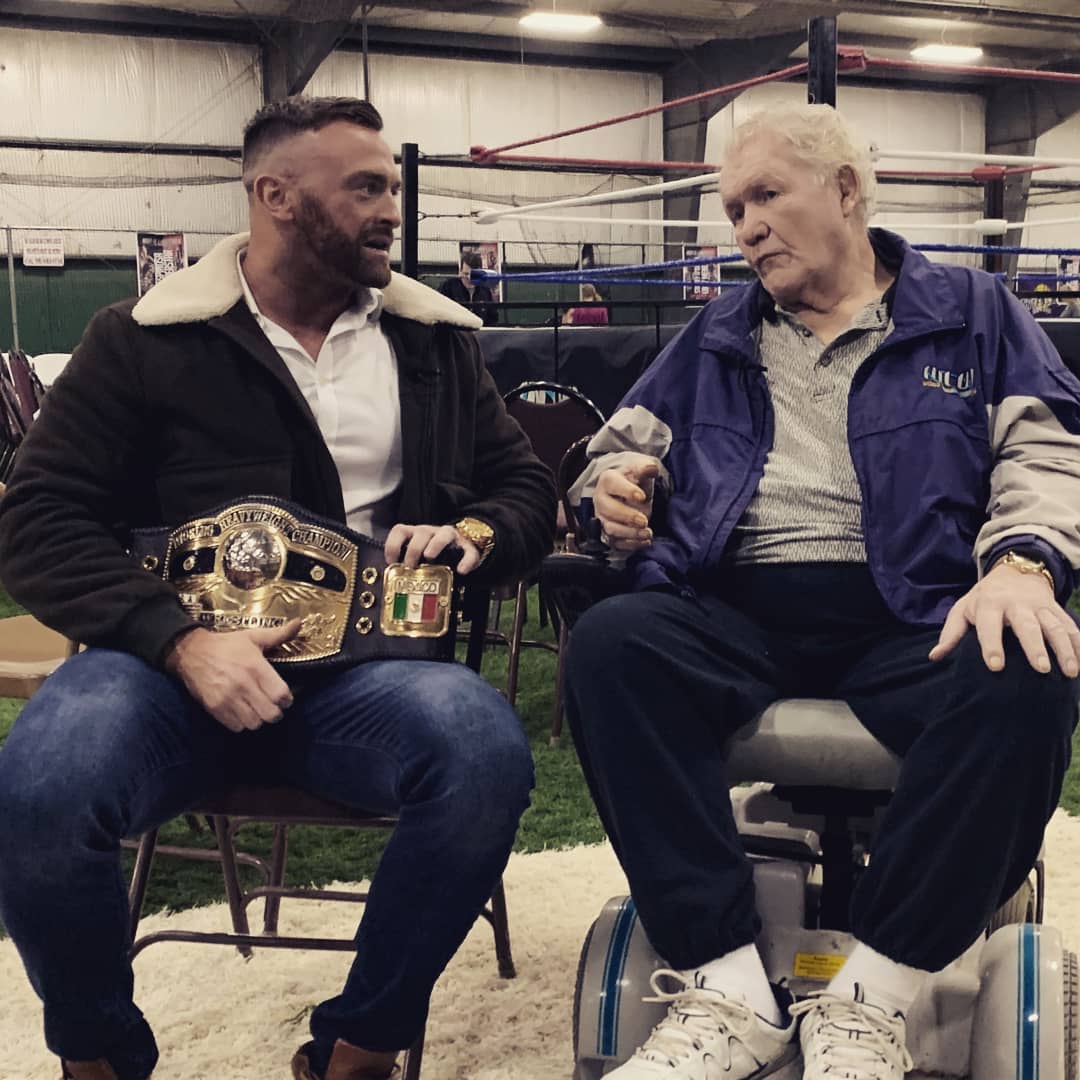

Two NWA World champions, Nick Aldis and Harley Race. Facebook photo

It wasn’t hard for Aldis to start rhyming off towns: “Skegness on a Tuesday, Bogner on a Wednesday, Minehead on a Thursday, back to Bogner and then back to Minehead and back to Skegness, and then we have Mondays off.” That didn’t include the other shows that Dixon would promote, perhaps bigger shows that were more of a spotlight and not just in a holiday town.

By Aldis’ estimation, “In that year, which was ’05 or ’06, he probably ran 350, probably maybe more, shows. Sometimes he had two or three teams out on the road at once.”

When Dixon’s death made the rounds, so many others chimed in: Gangrel, Sam Adonis, Stu Bennett / Wade Barrett, Bryan Danielson, William Regal.

“There’s so many of us who owe so much to him,” summed up Aldis.

Those smaller shows at vacation spots were a throwback to the territory days. Dixon referred to them as “cowboys and Indian” shows as everything was in black and white.

“They will always good, he always drew well, he knew how to promote. And we were so, so spoiled, because we just had night after night of wrestling in front of full houses, and full houses of family audiences with kids who were just like there for entertainment and yay, boo, and they weren’t, ‘This is awesome’ or ‘Fight forever,'” said Aldis, not with scorn for today’s fan but with a wistfulness, that there was a way to go back to something similar.

— with files from Bradley Craig

TOP PHOTO: Samuel Shaw and Nick Aldis, left, at the Harley Race camp in 2007; Jushin Liger and Brian Dixon. Facebook photos.

RELATED LINKS

Had the pleasure of working on a show that Nick Aldis was headlining (Ohsweken, Ontario) Septemeber 2022, and we discussed this very thing. To say I was bit jealous is putting it mildly.