To be a big star in professional wrestling is to have your name on the marquee. Very few ever got to the next step however — having a TV show named after you. For six years in the late 1960s and early ’70s, Championship Wrestling With Johnny Powers came out of Buffalo, proclaiming its Hamilton, Ontario-born star (and part-owner) Johnny Powers as the star of stars.

It is time to remember his stardom, as Powers died peacefully at his home in Smithville, Ontario on December 30, 2022.

He was born Dennis Arnold Waters in Hamilton, Ontario, on March 20, 1943, to Vera and Arnold Waters. As a youth, Waters played hockey, until he grew into the 6-foot-4 wannabe—285 pounds at age 17—that took a risk on an outlandish new career, his time at McMaster University studying geology having disenchanted him quickly.

Bruce Swayze was there when a youthful Waters walked into Jack Wentworth’s gym on Hamilton’s east side. “This kid walked in, he had a big towel around his neck. He was a tall, impressive kid. He had just finished high school at Delta Collegiate. He wanted to join the gym, work out, and become a wrestler. I’ll never forget it. I was covering the office for Jack Wentworth, who was out having lunch,” recalled Swayze. “He started working out. He had rapid gains, real fast. He was a quick study, learned the business quick. He was actually out on the road within two years.”

Having survived the training in “The Factory,” as Hamilton was known, he headed off to Detroit, still a teenager, where promoter Jack Britton dubbed him Lord Anthony Lansdowne, his Canadian enunciation apparently close enough to British royalty. At 20, he was a full-time wrestler.

“There were times when I really felt I was the mark, the kid from the east end of Hamilton going to the big city, downtown Detroit, the den of inequity, with all the hookers and the hotel, giving $5 blowjobs to truck drivers and charging the wrestlers more, I think,” Powers said in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes & Icons.

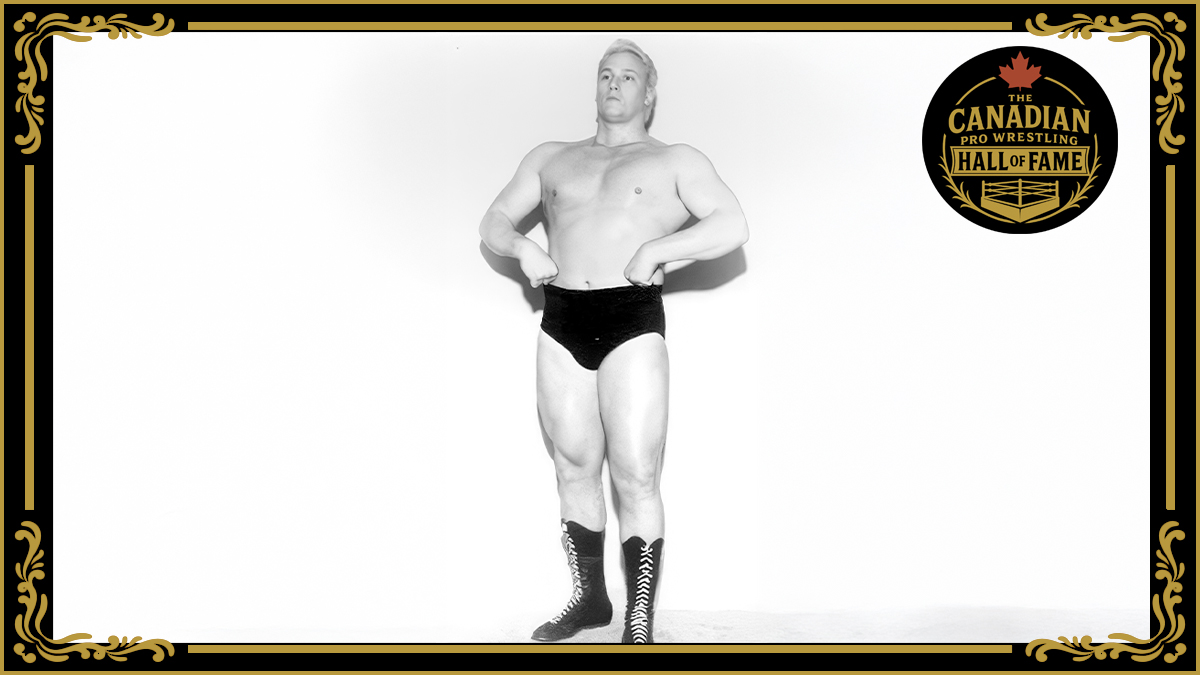

In Pittsburgh, he became Johnny Powers, with bleached blond hair, and got to the top of the cards, learning later in life that it was Bill Watts and Killer Kowalski that stood up to promoter Ace Freeman, saying “Don’t hurt the kid.”

“He’d come in for the show and he was the driver for the midgets,” recalled Watts. “Bruno and I were on a card and I said, ‘Bruno, you’ve got to watch this kid. He’s got a lot of box office.’ So Bruno put a word in with Ace Freeman.”

Powers created a style based on Lou Thesz‘s strong wrestling basics, Johnny Valentine’s punch mouth toughness and Buddy Rogers‘ show-stopping pace. He meshed his tae kwon do skills in with his natural frenetic wildness.

“My break came when I wrestled Bruno Sammartino in Pittsburgh,” Powers told SlamWrestling.net, recalling those days in 1963. His power move-based style worked well against the Italian strongman Sammartino. “I did a lot of ground work. I evolved a figure-four leglock into something that was called a Powers-lock. I had a lot of success with that. So, I worked strongly on the ground and strongly at the top.”

Powers didn’t go over Sammartino, who was the WWWF Heavyweight Champion, but it propelled him up the card for good. In a rematch in Philadelphia, Sammartio and Powers tangled again, with Tony Galento, a boxing champion as referee. That set the scene for a series of matches with boxing champions including such greats as Rocky Marciano and Joe Louis. Powers also had four professional boxing matches in his fighting career, and later tried promoting mixed martial arts cards in Ontario.

Yet main eventing wasn’t enough for Powers, who yearned for more. “By the time I was 22, I was bored with the wrestling side, so I was interested in the marketing aspects, the promoting aspects,” he said. Powers bought the rights to promote in a few Ontario towns, including Sutton (“took me three maps to find it at that time”), then Galt. Following the advice of Toronto promoter Frank Tunney, Powers then purchased part of Pedro Martinez’s operation in Buffalo. “We took it actually from a standstill that was a quasi-dormant territory, and when we finished, it was really moving. That organization had everybody from [Johnny] Valentine to The Sheik to [Bobo] Brazil. There was a lot of quality talent at that time.”

The Buffalo territory ran from western New York to Cleveland, and Powers became a star. He also worked with Martinez to change the way wrestling was marketed, taking the newly christened NWF and syndicating the TV shows around the world. Clients included the Armed Forces Television Network, Telesystema de Mexico, and the Japanese Television Network. “Within reason, I guess I was a pioneer at international syndication and I ran that as a part of National Sports Television in Buffalo.”

Through the Championship Wrestling With Johnny Powers program, Powers reached into the hearts of fans, facing down a wide variety of villains, utilizing his Power-lock leg hold to triumph. There were the traditionalists, like Johnny Valentine, the wildmen, like The Sheik and Abdullah the Butcher, and the unforgettable icons, like Ernie Ladd and Wahoo McDaniel. “I believe that separate from the fact I was an owner with influence, my longevity in a weekly territory primarily came from an adjustment to each heel’s style,” said Powers, “with me letting him play to his strengths and letting him get over.”

The Buffalo/Cleveland promotion would evolve into the National Wrestling Federation and established its own World title in 1970 with, naturally, Powers as champ. Neither the title nor the promotion lasted long, but its influence continued.

In 1967, he did the first of more than 30 tours of Japan. Powers established a friendship/rivalry with Antonio Inoki, leading the Japanese star to gain control of the NWF title—and basically what was left of the NWF promotion—in 1973, making it a Japanese-based belt, the World title in New Japan Pro Wrestling, shut out from the NWA World title by rival All-Japan. “I had some great matches with Inoki, who was a heckuva guy, just from the ability to move in the ring and keep going. I had over 50 matches with Inoki through the years,” said Powers, known as “The Iron Man” in Japan.

In Japan, he exchanged the NWF World belt with Seiji Sakaguchi and battled Inoki countless times. It was the first world title won by a Japanese wrestler, and in 1973, New Japan bought the NWF. “They bought, quote, the franchise, the rights to the National Wrestling Federation Association,” Powers said. “The baton got turned over to Inoki and association. So the titles got turned over, and the association got turned over.”

On an international scale during that time period, no one came close to Powers. “There is actually nobody that has the international exposure as a Canadian that I had for the period of time that I had it. Nobody in that era, the ’60s and ’70s, was going to Japan as much as I was and was doing Singapore and stuff like that,” he said. In all, he estimated that he did over 30 tours of Japan.

Besides the wrestling, Powers also got involved in promoting musical events like rock and roll revival shows and the Harlem Globetrotters. The idea of the spectacle led to a major show in Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium, where there were 50 wrestlers on the show, and three rings going at the same time, set up at home, first and third base.

Powers retired in 1982, but returned a year later for a series of matches with the proceeds being donated to charity.

“I had done 20 years in the business, and I was getting tired of it,” he said. Powers ran a wrestling school with Sweet Daddy Siki in Toronto for a time, and got involved in many other ventures. Siki noted that Powers helped at the school for less than two years, before Ron Hutchison assumed a role as trainer. “Johnny Powers, when he came in — I’ll tell you the truth — he’d show up once a month and get in the ring with some of the guys for 10, 15 minutes, and that’s about it, and takes off. I’m there every day,” recalled Siki.

The wrestling business was a wonderful learning opportunity for his next career. “I use my marketing side and my deal-making experience that I garnered from the wrestling business to carry me over,” he said. “I learned how to sell tickets, in other words. From a public persona standpoint, and also from a deal-making standpoint, and that has been a solid understanding.”

Powers has distanced himself from his old occupation. “When I retired, I said I was going to step away from the business,” he said. When the Japanese Wrestling Hall of Fame wanted to induct him, it took them two years to find him.

Yet Powers has no regrets about his past. “For the time and for the moment in its context, I achieved what I wanted to achieve. From the east-end of Hamilton, going up through a sport and ending up on top of the sport for a while, both as a competitor and also as a businessman.”

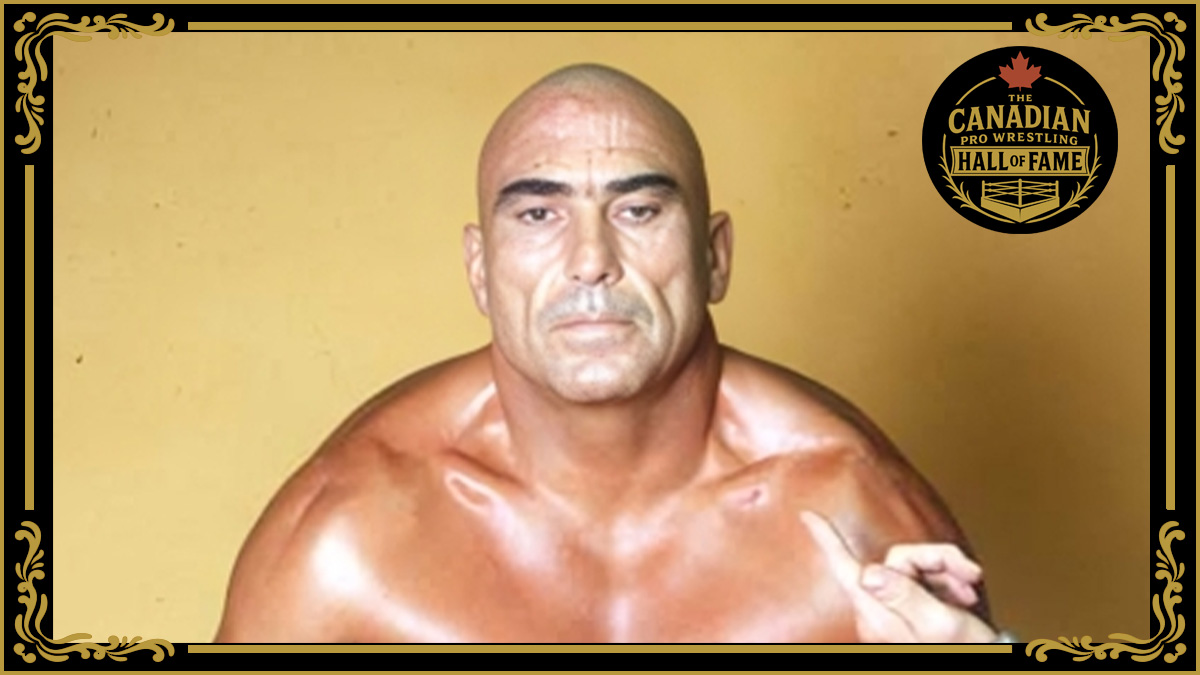

To the wrestling scene in and around Hamilton, Powers was a bit of a recluse. He didn’t attend the regular oldtimers luncheons organized by Ernie Moore, and rarely ventured out for wrestling events. With his hair gone and having gained a few pounds, he was unrecognizable to many. Osteoarthritis slowed him to a crawl, the result of many, many bumps. “It’s the same for many football and hockey players. We’re paying the price for it now,” he said in 2008.

Therefore it was a major moment when Powers arrived on January 28, 2018, at the celebration of the life of Johnny Evans, who wrestled as Rotten Reggie Love. “The reaction from everyone was absolute respect,” recalled long-time Hamilton fan Kevin Hobbs, who was there.

That might have been Powers’ last public appearance relating to pro wrestling.

He is survived by wife Rosalee Doering, son Sean Powers and grandchildren Peyton and Storm, daughter-in-law Shelly Powers and granddaughter Sienna, sister Jackie Hammond (Ron), niece Michelle Silver (Tim) and grandnephew Jacob Burns. He is predeceased by his parents Vera and Arnold Waters and his son Kirk Powers who passed away in 2020. There will be a celebration of his life later this spring.