EDITOR’S NOTE: This piece originally ran in Wrestling Revue in January-March 2004. It is reprinted with permission of Arcadian Vanguard.

I’ve been writing about wrestling for over 18 years now, and a fan just as long. But in just two-and-a-half hours on the phone with Ole Anderson on a Sunday evening in November, much of what I thought I knew about wrestling was altered.

Despite what people may think of the man as an individual — I dug out the quotes “tyrant”, “intimidating,” “cheap,” “loud” and “out of touch from my own files in 30 minutes — Ole Anderson is indeed a wrestling icon and one of the most influential people in the business over the last 30 years.

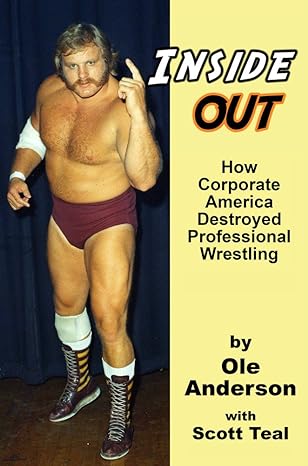

Now, he’s teamed with respected Whatever Happened To … writer Scott Teal to create his autobiography Inside Out: How Corporate Wrestling Destroyed America. You won’t find it in stores, only at Teal’s website. The book itself is a step up from the self-published genre, with Teal’s years of publishing experience creating a polished feel to the book.

But back to Professor Anderson. The interview was arranged to promote the book, to get the word out about it and direct people to the site to buy it. But boy, did I get much more.

He has a foul mouth and is extremely opinionated, neither of which is news to people who know him. Ole also likes to challenge you. He’ll start a thought, and expect you to finish it. Or ask you a question, and before you get a chance to answer, he’s called you too young/dumb/stupid/ignorant to know. It’s a test, and I didn’t do as well as I thought I would have.

Still, as they say, every cloud has a silver lining. The interview was challenging and draining, but ultimately rewarding. And it gives me a chance to share with the readers of Wrestling Revue magazine some lessons from Professor Ole Anderson.

WHY BOOKERS TEND TO PUT THEMSELVES OVER

It’s a common lament from wrestling fans: Bookers have a tendency to shove themselves (or their siblings) down the people’s throats. As a booker for years and years in Georgia, Charlotte and even in WCW, Anderson has his own thoughts on putting people over, and why bookers push themselves. “I put people over when I thought it was important to put ’em over and it would help them,” he said.

Anderson is never mentioned in the same breath as relentless self-pushers Dusty Rhodes, Fritz von Erich or Verne Gagne. Yet, he’s quick to remind you that he did put himself over. Just not all the time. “I did put myself over when it was needed, and I also put myself in a position where I’d let other people beat me when it was also needed.”

It is hard to find someone to trust in wrestling, so sometimes, you have to do it yourself. “If you’re the guy that has the belt, Verne Gagne in this case, he knows when he tells Verne Gagne what the hell to do that night in the ring, he’s going to have a pretty damn good match and he also knows he’s not going to have any argument. … he knows exactly what Verne Gagne is going to do, and so he doesn’t have to worry about putting the fate of the match or the crowd coming on some other guy, maybe the guy’s okay, maybe the guy isn’t okay. Because he knows that every time that Verne Gagne goes out there, Verne Gagne is going to do exactly what Verne Gagne wants him to do. Well, it was the same with me.”

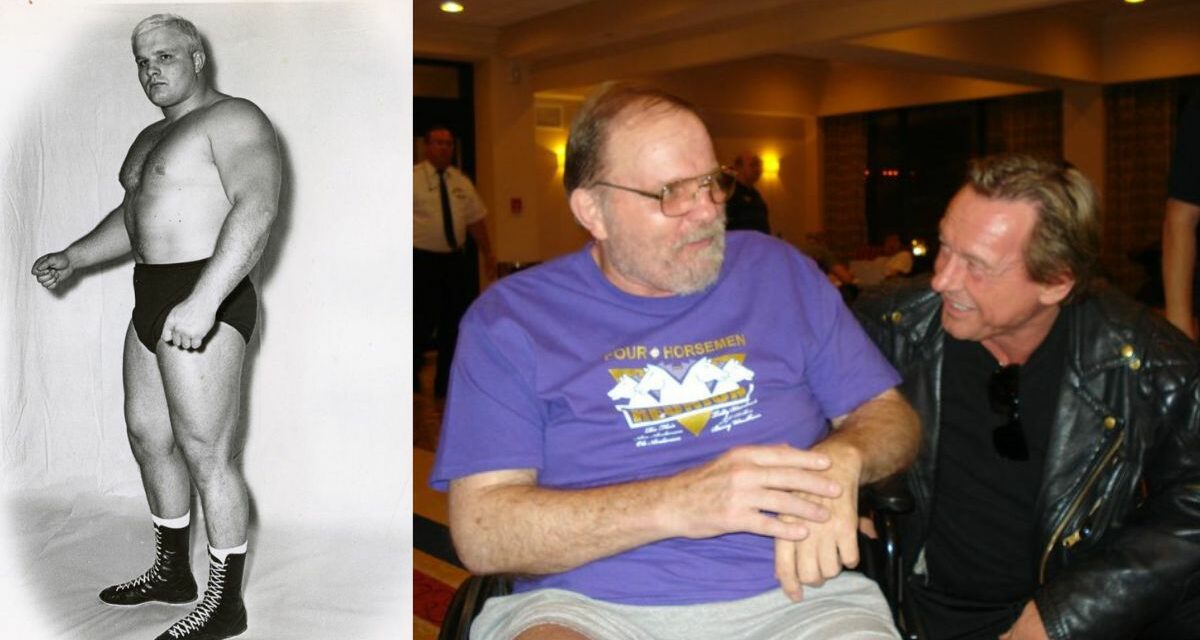

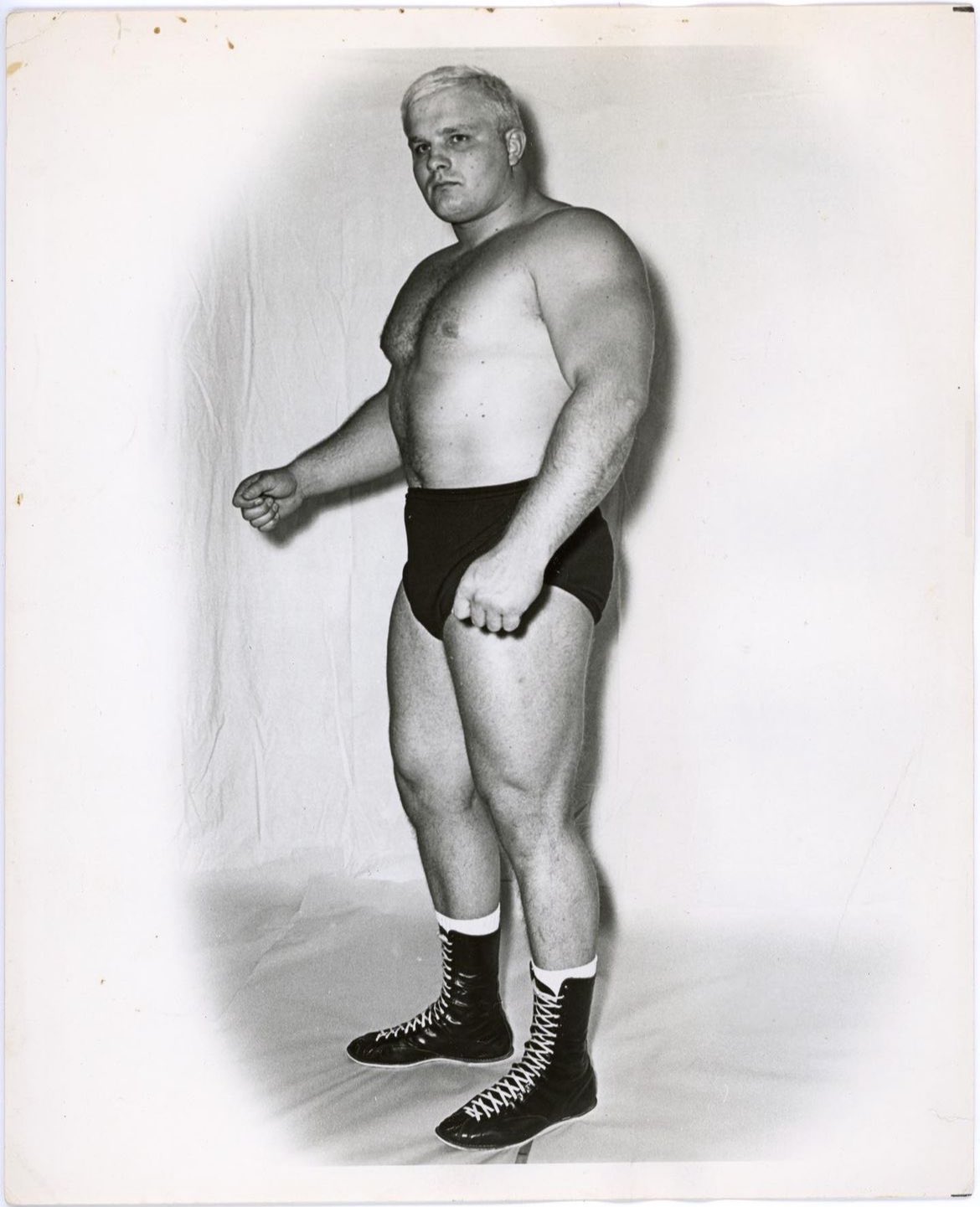

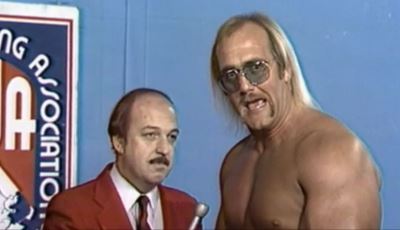

A young Ole Anderson.

A SUCCESSFUL WRESTLER OR TAG TEAM STAYS IN ONE SPOT (TRAVELING IS FOR LOSERS)

For your average fan, the life that the average wrestler leads is somewhat of a fantasy. Travel to far off places, see the country and the world, meet interesting people and come home to tell about it. Sure it’s rough on the family life, but it all works out in the end.

Bullshit, says Ole (and he says it a lot).

“For Gene [Anderson] and I to stay in the Carolinas for ever and ever and ever and ever, and in Georgia for ever and ever and ever and ever was because we were making money.”

He said that he got a call once about induction into the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame, and ended up in a debate with the caller.

“Yeah, so what do you want?”

“Well, we’ve got one little problem.”

‘Yeah, what the hell’s that?”

“Well, you guys [Ole & Gene Anderson] really didn’t go many places. You pretty much stuck to the Carolinas, and then Georgia and a little bit in Florida maybe. Individually, you were both up in Minnesota for a while.”

“Let me ask you a question. Why do you think we stayed in Georgia, why do you think we stayed in the Carolinas for so long?”

“Well, I don’t know. Maybe nobody wanted you in San Francisco? Maybe they didn’t want you out in Oregon?”

“Let me ask you a question. Let’s say I’m a wrestler.” [Ole asks him who he’s got in the Hall of Fame, who they are considering.] “Why did you choose them?”“Well, because they were in Oregon and they wrestled in California, and they spent some time down in Texas, they were up in Minneapolis, they also went to New York. Yeah, they went to the Carolinas, they went to Florida.”

“You ignorant son of a bitch. … Is that the kind of guy you would want to have in your Hall of Fame or would you rather have two guys who stayed in Georgia and the Carolinas? … If the fucking people that are running this Hall of Fame are as ignorant as you are, I wouldn’t want to be part of it.”

With a slap to the face, he’s back to his point. “The first concern to me, as I already mentioned, was to make as much money as I could make. So if I wasn’t making any money, I wouldn’t be in the damn territory no matter what. But, do you suppose for even one second that a guy would go to Florida, wrestle there for four, five, six months then pack up his wife and his kids, pack up his bags and head to Oregon to wrestle, wrestle there for a few months, then pack up his wife and kids and go down to California, wrestle there for a year, and pack up his shit and go to Texas, then pack up his shit again and go to Minneapolis because he wants to be in the fucking Wrestling Hall of Fame? No. He didn’t have a choice. He wasn’t able to make money in any of the places, so therefore he had to continually move. In fact, it wasn’t even his choice to move. Most cases, the promoter said, ‘Listen, your time is up. Goodbye. And maybe I’ll find a place for you to go, but if I can’t, you’re still going to be done.’ That’s one thing that nobody thinks about because they’re not either smart enough or they don’t know how the wrestling business works. Do you think that a promoter would keep anybody in any territory if they weren’t drawing money? Why would you do it? Just because you liked him? You liked to watch him take a shower? They had nice perfume or cologne?”

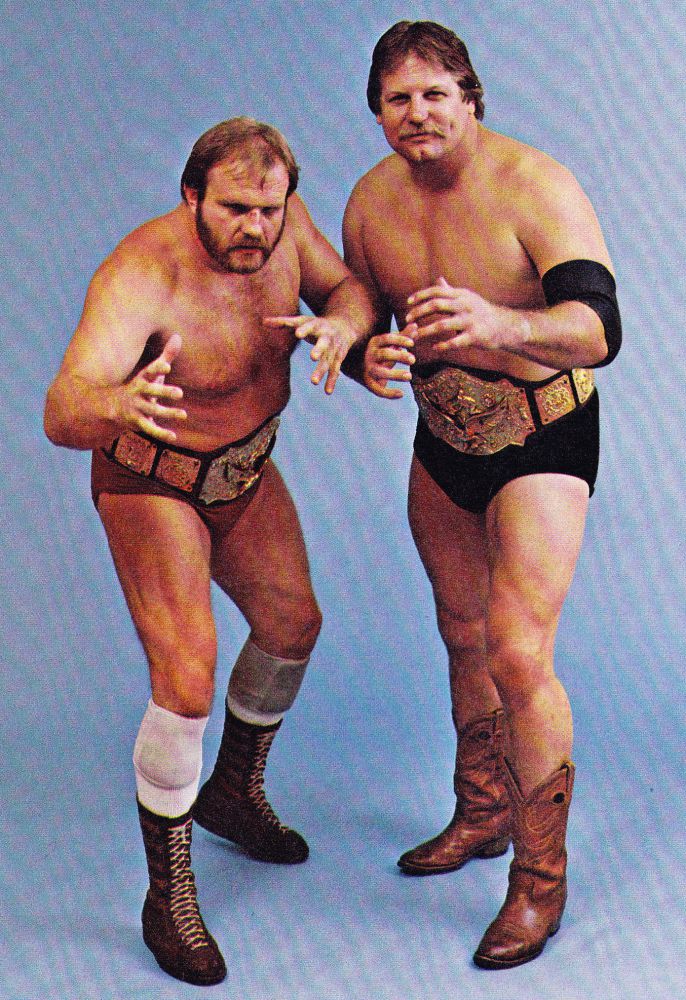

Ole Anderson and Stan Hansen from a 1983 Georgia calendar.

THE DEVIL WENT DOWN TO GEORGIA (AND MADE LOTS OF MONEY)

Ole is quite open about money, unlike a lot of wrestlers from the past. He is proud to have stopped wrestling at 40, with a good bank account, a nice house on a lake in the northeast corner of Georgia where he can look into South Carolina.

“Just for the hell of it, do you have any idea what the guys were making, in terms of money back in 1967? Or 1975, or 1978? Any idea?” he challenges. Given that I’m 32 years old, it’s hard to picture what people might have been making before I was born, but I hazarded a guess.

“$100,000?” I ventured cautiously. For top guys, like Bruno Sammartino.

A scoff and a pulled punch from Ole, but an acknowledgement that Bruno was indeed in that range his whole career.

Let’s go back to 1967, when he first started in Minneapolis for Verne Gagne’s AWA. A successful amateur wrestler, he was a natural to be trained by Gagne. Anderson bucked the trend though, and refused to be a referee or to haul the ring truck around like Gagne had made Bob Windham (Blackjack Mulligan) and Jim (Baron von) Raschke do.

A second guess is offered, $30,000?

“Dickie Steinborn and Doug Gilbert, they were Mr. Hi and Mr. Low, and the tag team champions in the early ’60s. I almost fell over, $15,000. That was their damn paycheck from the houses. … so let’s just say that was a bad year, or a few bad years, or whatever it might be. Let’s say they made $20,000. What the fuck is that?”

With a stomp to the solar plexus, we jump to the late ’70s, in the booming Georgia Championship Wrestling territory. “I paid guys here, in the late ’70s, Stan Hansen, Tommy Rich, Mr. Wrestling II, they made anywhere between $90,000 and $100,000 in a little damn territory. So I kept Wrestling II for ever and ever and ever. I kept Stan Hansen for ever and ever and ever. I kept Tommy Rich for ever and ever and ever. Why? Because I was making money with them. As long as I could keep making money with them, I could stay. If they gave me any shit, and I didn’t make money with them, they’re out of here.”

Ole is not about the little people. “All the little guys who were underneath that I didn’t give a fuck about, that didn’t make any money for me and were just filling up the card, they got to go all over, because I didn’t want ’em! So they went to Texas and they went to Oklahoma, they went to California, and they went to Oregon, they tried to get to Minneapolis and they might have gone to New York, and they might have gone to Florida, and they might have gone to Detroit. So they’re the guys that are going to get into the Hall of Fame, because they’ve been all over.”

Gene Okerlund and Hulk Hogan in the AWA.

THE HOGAN SUCCESS STORY: GETTING OVER IN A BIG TERRITORY

It’s a given to most wrestling fans that Hulk Hogan was the right man in the right place at the right time to get over like a mega-star. He had to have been in a territory like the AWA or WWF that featured big men, a series of obstacles for the good guy to overcome and eventually prevail over.

But Ole made me think about something I never had before. It was that Hogan was in a territory with big wrestlers; he only succeeded when he did because he was in a BIG territory.

Of course, Ole booked Hogan back in the day, about 1978, when he billed him as Sterling Golden in Georgia. “He was the shits. He was a great kid … he had the look but what would you do with it? The only way you could possibly use him was if he went to a territory like New York or like Minneapolis, because we used to run towns on a weekly basis.

“So if you put Hulk Hogan back at the very beginning in the towns down here in Georgia that we ran week after week after week after week, it would take the people about two days to realize he didn’t know his ass from a hole in the ground. If you took him to New York, and you were careful, and you put him over somebody who knew a little bit about being in the ring, you might have the chance of making Hogan look like something. And the guy who really made Hogan Hogan wasn’t New York, who was it? Verne Gagne. But Verne also had the luxury of being able to put a guy in Minneapolis, and he didn’t have to worry about coming back for two or three or four months. Hogan didn’t overexpose himself.”

Looking deep into the recesses of my own memory, it all makes sense. Here in Toronto, we’d only see Hogan a couple of times a year during his WWF tenure, and therefore fans would ache for him to make another appearance.

THE POWER OF TBS

The reach of WTBS continued to grow during Ole Anderson’s stay there. And as its power grew, so did the booker’s ability to bring in whatever talent he wanted.

“Anybody who was anybody for the most part was happy to come into Atlanta because of the television exposure,” he explained. “We used to take people from territories all over because in truth, a lot of territories were upset about the fact that we even had that television that was going all over. So to even placate them to some degree, we used their talent.”

There was nothing formal in writing, and it never came up at the NWA meetings. Ole would just call up a promoter and see who he wanted to send, or the promoter would call up and ask to give someone a little more exposure. “It’s not that they needed it, it’s not that they begged, it was the just the idea that it gave me a different look, have a few different people to make our television look a little bit different. It also reinforced their territories because now, instead of a guy being a local guy staying Kansas City, all of a sudden, he’s an international star because he’s been on Atlanta TV, that’s all.”

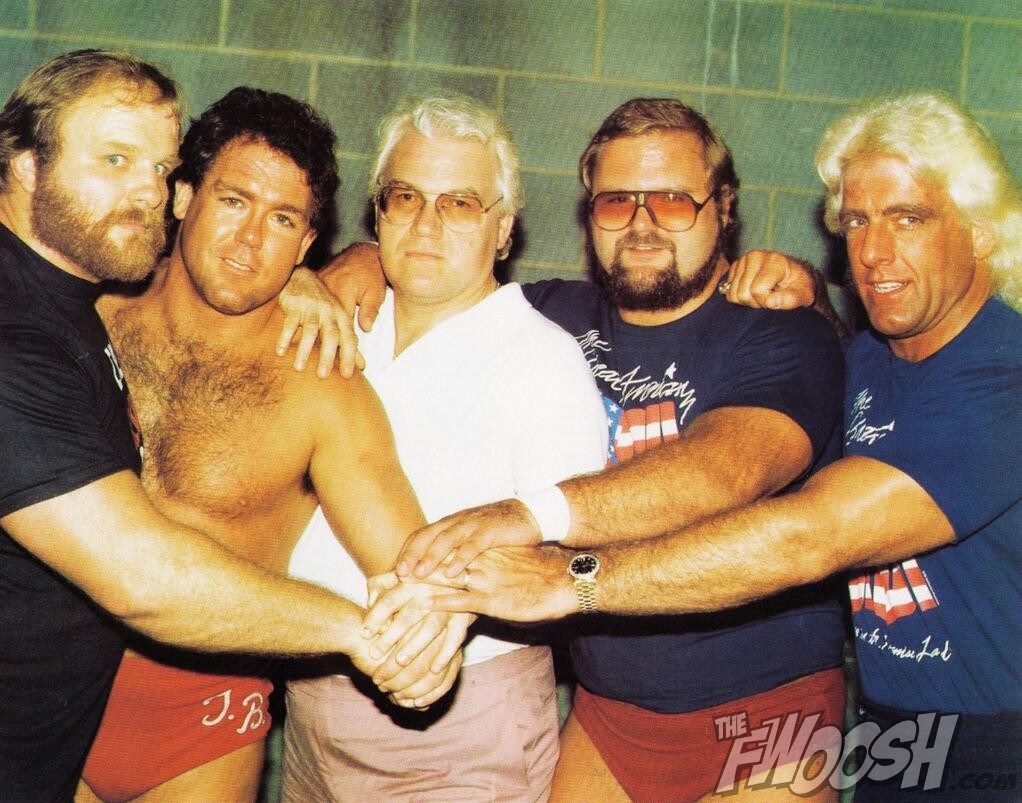

The Four Horsemen of Ole Anderson, Tully Blanchard, JJ Dillon, Arn Anderson and Ric Flair.

A BIG WHAT IF: BLACK SUNDAY ON TBS

In 1984, Vince McMahon bought out the TV time from Georgia Championship Wrestling and put his growing WWF empire onto the nation’s only SuperStation, Channel 17 from Atlanta, better known as WTBS. The outcry was immediate from the long-time fans. They didn’t want the cartoons, they wanted their heroes and their villains back. Within two weeks, they were back.

As the booker at the time, Ole Anderson was caught in the middle of it all. Needless to say, he didn’t appreciate the arrogant McMahon coming in and throwing his weight around. From the get-go, they were like oil and water, unable to exist together in the same room. Ole’s book recounts more than a few tales of the takeover, including instances where he told off McMahon and his wife, and even had him thrown out of the building.

Yet, in hindsight, Ole realizes that he missed out on something. (Not that he regrets it — he just realizes it.)

“If I had had a fucking brain, you know what I would have done? You know what I should have done? … I should have said, ‘Damnit Vince, you’re the smartest son of a bitch in the whole fucking world. How much do I get?'”

Having been in the business for 20 years at that point, Anderson had faith in the men he worked with on a regular basis. “I was stupid enough to think, number one, that the rest of the promoters, from Verne to Jimmy Crockett to Bill Watts to Don Owen to whoever, wouldn’t allow Vince McMahon to take over wrestling. I was stupid because I miscalculated everybody, thinking that I know something about people. I really hit an all-time low, because I didn’t factor in the idea that these guys had such tremendous egos that there was no way that they could agree to formulate a plan where we could all work against Vince McMahon.”

When Georgia Championship Wrestling reclaimed its spot on TBS, Anderson says that he pushed for expansion then, that the time was right and they had THE station to make it work. “I made the comment to the people at TBS, ‘Listen, right now with this television station going all over the United States, and then some, this could be the mecca for wrestling. This could be the biggest damn wrestling city in the world.'”

Instead, he ran into small-minded, southern thinking; that a little old southern town like Atlanta couldn’t possibly compete with New York.

As hard as that is to comprehend, remember this was only a short while before Atlanta hosted its first Super Bowl, went to the World Series and held the Olympic Games.

Superfan Peggy Lathan and Ole Anderson

LAMENTING JOBS LOST

There’s no denying that pro wrestling has changed over the past 20 years. Ole experienced it all, hanging on in WCW until he became just another expense to cut from a bloated, corporate takeover. (Eric Bischoff did the dirty work.) At the end of his time there, having been dismissed from booking duties, he worked out with wrestlers, sharing his years of knowledge.

The guaranteed contracts in WCW and the “downside guarantee” deals in the WWF had changed the desires of the wrestlers, he said. At different times, he worked out with Sting, Steve Austin and Lex Luger, but they all came to the realization that they didn’t have to work as hard as Ole had for a job. It was handed to them on a platter.

The end result of the laissez-faire attitude of that generation means that there is really only one option for full-time work in wrestling, maybe a hundred full-time workers where there used to be thousands.

But to focus solely on the jobs lost is to miss the bigger picture, said Anderson. Where there used to be dozens of shows each and every night across North America, now there are two major WWE events and an occasional independent show.

It’s mind-blowing to think about what a hotbed of wrestling the southeastern U.S. was during the 1970s and into the 1980s. The territory system was peaking. “Let’s take a year during the ’70s, let’s take 1975 just for the hell of it. Georgia was running three towns a night, except on Fridays when we ran two or one, depending. And there was opposition from Ann Gunkel, who was running two towns a night. So you could basically say in Georgia, on any given night during the week, you would have as many as five towns that had wrestling, which also translates into saying you probably had in the neighborhood of 40-50 guys that were employed as wrestlers. At the same in the Carolinas, they had three towns a night as well. Sometimes we ran as many as five towns a day in the Carolinas.”

As the booker, Anderson would try to get to as many shows as he could. In his absence, he’d usually leave instructions for a referee that should be followed. “On a Saturday, for instance, I wrestled two TVs here in Atlanta, I wrestled on TV in Columbus on Saturday afternoon and I wrestled that night in either Griffin or Carelton. So I handled all those towns that I was in and all those TVs I was in.”

Yet the bottom line to the booker isn’t what they did in the ring that particular week, it was the attendance the following week. If his carefully-laid-out plans had been followed, attendance should rise for the subsequent weeks. “I could find out if [my plans] were done or not very simply by asking somebody what the crowd reaction was, which may or may not be a clue — it doesn’t mean everything, but it gives me some idea. And the better proof is what? …. What happened the next week! If next week went down, somebody screwed up someplace. Now maybe they didn’t do it exactly how I wanted, maybe it wasn’t done exactly how it should have been done, but if it was good enough to draw more money again, so you have to say, okay, it must have been close.”

UNCHANGED MELODY: DRAWING HEAT AND TV VIEWING

We’ll close with some thoughts from Ole on drawing heat and viewers, intertwined as they are.

He thinks that the number of wrestling fans has stayed fairly consistent through the years as populations grew in metropolitan areas. Television is available to almost everyone, yet the fragmenting of the audience to the 500 channels is a new challenge. Still, to Ole, the principle is pretty simple. “If you had something that was worth watching in terms of professional wrestling, the people would. The fact that there’s a million channels on the television isn’t going to change it because I’ve got a million channels on my TV, and my TV is off. Why? Because there’s nothing worth a shit to watch! And I would be happy to have something to do.”

The obsession with quarter ratings of Raw and Smackdown! make Ole laugh even harder. “They’re analyzing it. Why? Because they don’t know what the fuck they’re doing. They’re not doing good, they’re doing bad! And they are trying to find out what the good is from the bad so they can figure out how to duplicate the bad and maybe erase some of the bad. But they’re so horrible and they’re so stupid that they don’t have any idea what they’re doing, so that’s why they’re coming out with a break by break by five minutes by 10 minutes, or whatever it may be. ‘Now, who was in this period? The damn ratings went up? Who was there? Now, what did they do?’ They don’t have a clue what’s going on. This is the 21st Century, this is all different, TV of the 21st Century is a lot different than the TV in the ’60s and ’70s. No, it’s not. People turn the fucking TV on and they watch. If they like it, they stay tuned. That’s all. If they don’t like it, they turn it off. It’s as simple as that. If there’s nothing on television that encourages them to go to the wrestling matches, they don’t go there either.

“Vince and those people up there that run that damn thing, they just don’t have a clue. And they never will have a clue, they never will, because they’ve never been down there in the ditches, trenches, to know how to make it happen. I was asked, several years ago, what I would do if I got the opportunity to run Vince’s show, if I got the opportunity to run Ted Turner’s show. I said I wouldn’t take it. They said, ‘What do you mean?’ I said, ‘Well, nobody knows how to do what I’d want to have done! They just don’t have a clue.'”

Especially at TBS, he ran into suits who figured that wrestling was such a simple proposition — put two people in tights in a ring and the people will come — that anybody should be able to do it.

“A lot of guys tried it. A lot of guys couldn’t do it. If you look at what causes people to come to wrestling, and you realize that the biggest thing that’s involved in my mind, anyway, is the human emotions. And if you’re going to tell me that human emotions have changed because it’s the 1990s or the 21st century, it’ll tell you, number one, you’re an ignorant mother son of a bitch. People still love, people still hate, somebody wants to screw his neighbor’s wife, somebody wants to kill his neighbor, somebody wants to rob somebody or shoot him, or whatever it might be. The emotions we have as humanity haven’t changed for thousands and thousands of years.”

Wrestling was never about being real or fake, it was about making a fan believe in something, whether it was backing Wahoo McDaniel as he fought against the odds or that Roddy Piper really was crazy. According to Anderson, who was stabbed seven times during his career, the primary thing that has been lost is the ability to create doubt in the minds of the viewers. “Why would anybody willingly come down and stab me, because they have to think at some point that there might be consequences for their actions, which of course could lead to jail. But no. They were so caught up in the whole damn thing that nothing made any sense to them but that they wanted to hurt me anyway they could. Go to a match today, and tell me who gets upset.”

Close your notebooks, class. Today’s lesson is over.

TOP PHOTO: A young Ole Anderson; Roddy Piper listens to Ole Anderson in 2011. Photo by Peggy Latham

RELATED LINKS