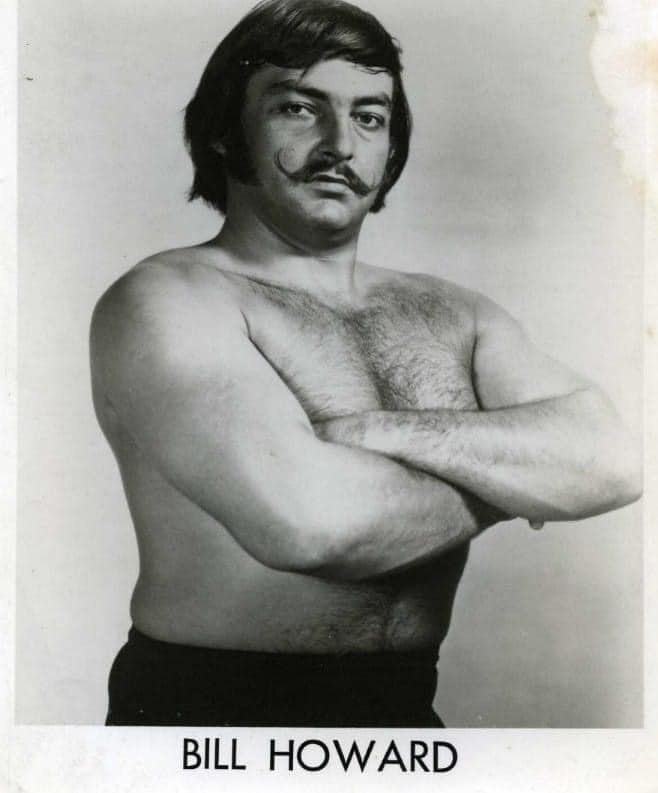

Howard Newell, who lost plenty of matches under the ring name Bill Howard, had the in-ring instincts of a winner until the end.

Battling against chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), his son Frank was at his bedside, a few days before Howard died on Saturday, October 7, 2023, at around 10 p.m.

“He went through an episode again and we didn’t know if he was listening or not. I leaned down and I go, ‘Dad, you’re gonna kick out again, aren’t you?’ And he kind of shook his head and I went, ‘One, two …’ and I swear to God, he kicked his right foot,” recalled Frank Newell a few days after his father’s death.

The late manager Gary Hart once praised Howard and his ilk. “Bill Howard, yes, made a great living as a middle of the card wrestler — I don’t know how great, but he made a living. There were tons of guys like that,” said Hart. “They’re so important to wrestling. Someone has to get you over. Someone has to work on the first match, second match, third match, fourth match, fifth match. In a perfect world, all of those matches have to be good.”

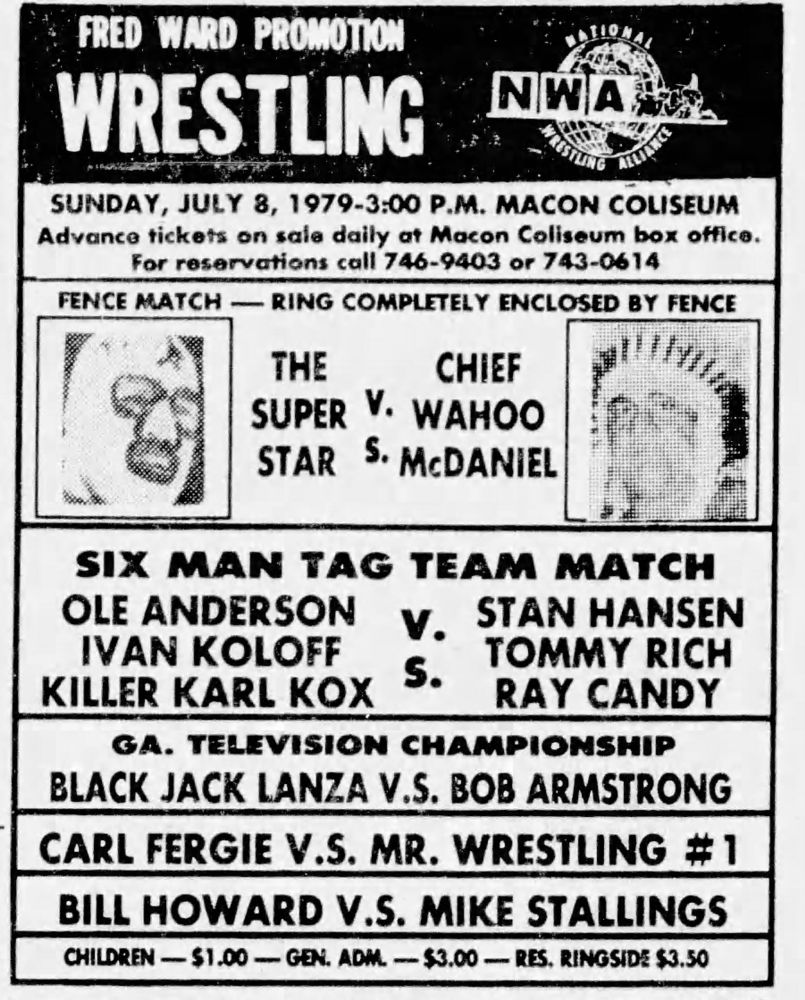

Bill Howard in an opening match in Macon, Georgia, on July 8, 1979.

Howard Newell was born on May 12, 1945, in Burlington, Wisconsin. He was not a big man, 6-foot, struggling to get to 200 pounds consistently.

He left home at age 15 to join the circus, and did a variety of jobs, including wrestling bears and alligators. A bear claimed part of his middle finger.

In a 2006 interview with this writer, Howard shared how he got into pro wrestling — when he was only 16 years old.

“I was going with this girl in Chicago and we just talked about it. She and I called Billy Goelz, who had a school at the old Marigold Arena, him and Johnny Gilbert. I just went down there and started training,” he recalled.

As the newly rechristened Bill Howard, he worked mainly outlaw groups to start. “At 16 years old, nobody took you too serious,” he said.

Then he wrestled a bit for Jack Pfefer when the notorious promoter took over Chicago after Fred Kohler retired. Pfefer was a real character “almost to the point he was a real pain. He was funny. He had a fingernail that was real long that he used to stab pickles with,” said Howard.

From there, the breaks came pretty easily. “I never had a problem at all, never. I don’t know why … Actually, I can’t ever remember anybody sending me anywhere. I made all the calls myself,” he said.

“Colonel DeBeers” Ed Wiskoski, who knew Howard in Kansas City, described the benefit of not being a top guy. “He enjoyed his position, had a lot of laughs and made a little money,” Wiskoski said of Howard. “Back then, if you could make a living and do jobs, there was no pressure. Nobody would point fingers, ‘Oh f***, you can’t draw, you son of a bitch.'”

Howard didn’t have a problem with that description. “I got out of it what I wanted. I never wanted to be a star. We’ve got mirrors in our house, and I look and say, ‘You know what? I wouldn’t pay to see me, and I don’t think anyone else would,'” he cracked.

After all, this was someone who once told Verne Gagne, who was heading out for the main event, “Think of all the late movies and cold beers you’ve missed.”

“It was fun underneath. You got out of there early,” Howard said.

Each territory treated its enhancement talent differently when it came to pay, he explained. “In Kansas City, the payoff from the top to the bottom wasn’t that much of a difference. St. Louis, if you were on top, you got more than I did. I think the guys on top were making $450, $500 a week, and the guys underneath were doing $350 a week,” he recalled. “Minneapolis, yeah, there was quite a bit of a difference. Charlotte there was a tremendous difference between the guys underneath and the guys on top.”

When new talent was starting up, the so-called “jobbers” were called upon to help the rookies get their ring-legs. Among the wrestlers Howard worked with early in their careers were Ricky Steamboat and Hercules Hernandez.

That’s not to say Bill Howard wasn’t ever a featured performer. After Hercules Cortez was killed in an auto accident 1971, Howard toured Japan as Red Bastien‘s tag team partner as AWA tag champions. In all, Howard did four shorter tours in Japan, three or four weeks at a time, once for All Japan and three times for the IWA.

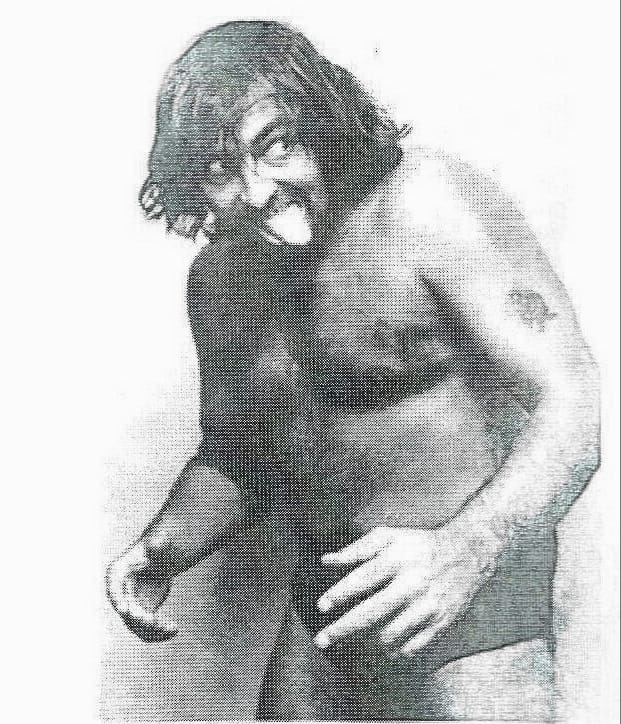

Bill Howard as Ratamyus.

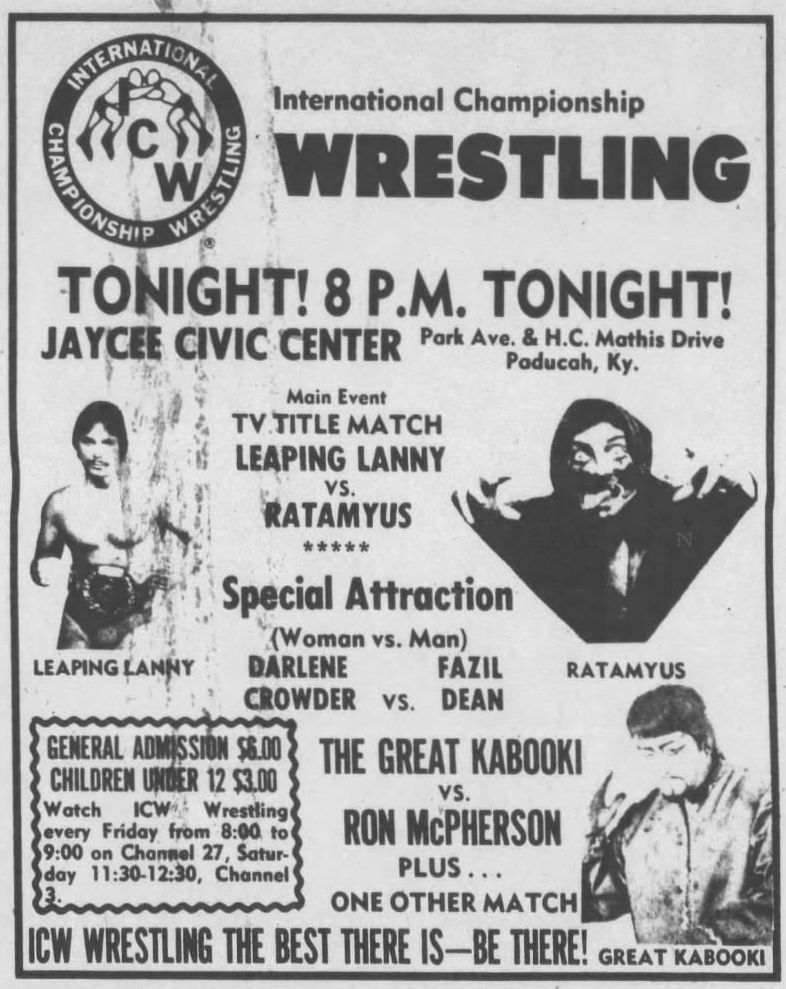

Then there was the only other name that he ever used: Ratamyus.

“His biggest claim to fame, of course, was the Ratamyus gimmick. Of course, we could never talk about it,” chuckled Frank Newell. That was in the outlaw ICW promotion run by Angelo Poffo. “He grew up with Angelo Poffo, Angelo Poffo was from Downers Grove, Illinois. My dad was from Burlington, Wisconsin, so they knew each other from kids. So, when they were ready to push Randy, and ready to push Lanny, my dad went and did it. So my dad had a lot of Randy Savage‘s first matches. And a lot of them were as Ratamyus in the southeast, mostly, but he was with them for a long time.”

An ICW show from Paducah, Kentucky, on Sunday, November 28, 1982

Ratamyus was also the name Howard used in Puerto Rico. “I never even thought there was much pressure on top. We were on top in Puerto Rico, and it was a piece of cake. I didn’t see any pressure,” said Howard. In Africa, there was no pressure, none whatsoever.”

Right, South Africa. Howard had been hired to be the booker there in 1984.

He’d been wrestling in San Antonio, getting ready to quit wrestling. It was there that he met Steve Simpson, whose father, Sammy Cohen, was the promoter in South Africa. They were workout buddies, and one night in the gym, Simpson simply said, “My dad wants you to come to Africa.”

“So I figured, ‘Hell, I can’t pass that up,'” said Howard. It wasn’t really a money move, but it was a chance to book some friends on the tours.

“Sammy took pretty good care of everybody as far as buying food and stuff like that. He paid for the hotel and all the transportation, so really, there weren’t a lot of places to spend money unless you bought trinkets from the Zulus,” explained Howard.

At that time, Johannesburg was one of the most dangerous cities in the world. Howard saw that first-hand. “I went down there with Bobby Jaggers. You couldn’t go anywhere on the street. There were little gangs all over the place. Two guys that Jaggers knew from before then on another tour he was on, they picked us up at the airport, and that night, they were both shot in a bar.”

At one point, Howard arranged for “Nature Boy” Roger Kirby — one of his best friends — to go to South Africa. Kirby was often matched up with the notoriously tough to work with local hero, Jan Wilkins. “All I got was a postcard from him. And on the postcard it said, ‘What a thing to do to a friend.'”

It’s Kansas City, Missouri, that Howard is most associated with, since he settled there. It was where his wife, Judy, was from. They had just the one son, Frank. The Newells enjoyed watching their grandson, Peyton Newell, play football at Nebraska (2014-2018), as a defensive lineman. Another grandson, Bradyn, is currently in high school.

Wrestling was around the family all the time, said Frank Newell. Bob Orton Sr. and Rufus R. Jones were regular visitors to the family home on weekends. Christmas cards would come from the McMahon family. Howard and Bobby Heenan were “inseparable,” said Howard’s son. “They talked every day and grew up together and wrestled together and so on, so forth.”

“I was fortunate. I was the kid that got to jump off Andre the Giant‘s shoulders in the pool. Kim Duk, was an old wrestler, Kim Duk taught me how to swim,” reminisced Frank Newell.

Where Kansas City was once home to dozens of retired wrestlers, it’s down to just a handful. Akio Sato and Mike George kept in touch locally. “He always got down” hearing about another death, said Newell.

Howard didn’t go out of his way to talk about wrestling, said Newell. “I tried to put a microphone in front him, I go, ‘Dad, just 30 minutes before you go to bed each night. Just tell stories.’ You can imagine the stories back when it was $50 payoff, a six -pack and everybody jumped in a vehicle and went to the next town.”

Bill Howard post-wrestling.

As Howard got sicker — he had a close call during the COVID-19 pandemic — his son would find himself quizzing him about wrestling.

“One of the websites had that he had over 1,688 matches and I asked him that. He said, ‘At least … that doesn’t count as a manager and as a referee,'” recalled Newell.

When Howard stopped wrestling, Terry Garvin hired him as the local referee for WWF in Kansas City, though he went into Iowa often, and occasionally afield to places like Phoenix or Las Vegas. It was part-time work.

“It worked out great for me because I still had my job,” said Howard, referring to the floor and carpet cleaning company that he ran, LIK-NU Carpet & Upholstery Cleaning, and which his son worked for a time. At one point, Judy Newell ran four beauty shops. Together, they peaked employing about 130 people between the two of them. “That can be pressure,” said Howard. He was a fill-in a couple of times too in the WWF: June 13, 1986, Hart Foundation (Bret Hart/Jim Neidhart) defeat Bill Howard/Lanny Poffo at house show at Kiel Auditorium in St. Louis, MO; March 21, 1987, Rougeau Brothers (Jacques Rougeau/Raymond Rougeau) defeat Bill Howard/Terry Gibbs at 1:59 at Superstars of Wrestling TV taping at Thomas & Mack Center in Las Vegas, NV; March 22, 1987, Koko B. Ware defeats Bill Howard at 2:24 at a Wrestling Challenge TV taping at Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Phoenix, AZ.

The refereeing was for fun, and ended in 1990 when it just wasn’t fun any more. “Business was exceptionally good. You never heard of a $80,000 house in Wichita, Kansas before, and you’d never heard of a $300 or $400 payoff for refereeing before either, and that’s what we were getting.”

Pro wrestling was at the core of his father, said Newell.

“He was always the job guy. He loved it, because he loved the business. He loved people, he just loved everything about it,” he said.

In February 1989, both Vince and Linda McMahon testified under oath at the New Jersey State Senate that pro wrestling wasn’t on the up and up, with the goal of deregulating wrestling in the state. It became major news.

Howard took it to heart, said his son. “My dad literally did not come out of the house for three weeks, did not come out of the house, he was so pissed off. He was just so sworn to secrecy.”

Howard was preceded in death by his mother, Dorothy, his father, Dr. Frank Newell. Howard is survived by his wife of 51 years and caregiver, Judith Newell; his son Frank (Stacie); grandchildren Peyton & Bradyn and a host of friends. A celebration of Life, with snacks and drinks provided, is scheduled for Saturday October 21, 2023, from 3-6.sharing of memories, begins at 4, at the Seven Bridges Neighborhood Community Center, 17800 NW Seven Bridges Rd, Platte City, MO 64079. More information at the funeral home website.