On February 21, 2023, Japanese pro wrestling legend Keiji Muto wrestled not one but two retirement matches to finally bring his in-ring career to a close. Muto, who also spent decades wrestling as his monstrous alter-ego The Great Muta, wrestled a total of 2,923 between October 5, 1984 and his retirement show, “Keiji Muto Grand Final Pro-Wrestling Last Love, on February 21st. With those two losses, Muto can finally hang up his wrestling boots after an incredible 38 years of grappling, promoting, managing, and changing the pro-wrestling landscape in different ways.

Like many Japanese wrestlers, Muto entered pro wrestling with a background in martial arts and amateur wrestling. With those foundations, Muto received training from Hiro Matsuda (the same man that broke Hulk Hogan in) and then began wrestling all over the world. He followed the generally-accepted wrestling practice of going on foreign excursion to learn about different styles and hone his skills. It was during this period in the mid-to-late 1980s that he wrestled under different names and gimmicks, including White Ninja (in Championship Wrestling from Florida), The Super Black Ninja (in Puerto Rico and WCWA) and Space Lone Wolf (in New Japan in 1986).

But it wasn’t until 1989 that things really took off for him. A week after his last match in WCWA as the Super Black Ninja, Muto appeared under his famous alter-ego for the first time (albeit with a misspelled name “Mota” instead of “Muta”). It was a short match but it was all the introduction he needed to begin his rise to superstardom.

Within a few months, Muto, as Muta, found himself in top matches in the NWA. His feud with Sting is still regarded as the stuff of legends. He began sharing the ring with the likes of Scott Hall, Terry Funk, Ric Flair, Arn Anderson, and “Dr. Death” Steve Williams. This one-year run of Muta’s was so successful that it created many life-long fans of Muta’s, many of whom still look over his 1989-90 run in WCW with fond nostalgia.

Muta would return to the NWA (and later WCW) over the years, but it was his work in Japan that transformed him from a highly-athletic wrestler into a legend. His work in the United States allowed him to add more personality to what he did in the ring and gave more oomph to the various new moves he either came up with or popularized. Whether he wrestled under his real name in New Japan or as his painted up alter ego elsewhere, it was common to see Muta hit explosive moves like his flashing elbow, a corner handspring elbow drop into a bulldog, and his patented Muta lock, an Indian deathlock combined with a backwards bridging facelock. He also popularized the Asian mist – which was a gimmick first introduced by the Great Kabuki – as well as the diving moonsault – which was created by Mando Guerrero and used by Leaping Lanny Poffo – and made them into his trademark moves. On many occasions, all Muta needed to do was spit mist in someone’s face to get a huge reaction.

With such an incredible appeal and impressive display of athleticism on his feet, on the mat, or in the air, it’s no wonder that Muto/Muta became such a successful wrestler.

In 1992, Muto continued pushing boundaries of what he could put himself and his opponents through in the ring. Not only did he want there to be a visual distinction between Muto and Muta, but he also wanted there to be a stylistic distinction as well. Muto was your bog-standard fiery babyface that channeled fighting spirit and never gave up. It was a simple but timeless gimmick that, coupled with his high-risk offense, made him easy to cheer for and rally behind. In contrast, Muta was every bit the monster he dressed as: unpredictable, remorseless, and excessively violent. Muta wasn’t above using weapons and putting his opponent’s life in danger.

This was put on full display on December 14, 1992 when Muta and Hiroshi Hase wrestled their bloodiest match yet. That match became famous among wrestling fans for reaching (at the time) new heights of bloodiness in a wrestling match. It led to the creation of the Muta Scale, an informal rating of match bloodiness, with the amount of blood Muta lost here serving as the template (1.0). To this day, only a handful of widely-known matches have seen more bloodshed than this one.

But it was only onwards and upwards from there. Muto was the first of New Japan’s Three Musketeers (Muto/Muta, Chono and Shinya Hashimoto) to win the IWGP Heavyweight Championship. He was one of NJPW’s main defenders against Nobuhiko Takada’s UWFi invasion that dominated the promotion from 1995 to the end of 1996. And if there was every any proof of Muto’s popularity, it was his first Tokyo Dome main event. NJPW v UWFi All Out War took place on a Monday in October, nowhere near any major holidays. And yet, in one of the rare cases of non-hyperbole in wrestling, the show drew a legitimate sell-out of 67,000 fans as Muto defeated Takada in one of the highest-drawing wrestling events in history. And if that still wasn’t enough, Muto and Takada did almost the exact same numbers in the Dome three months later.

Muto spent the rest of the 1990s as arguably New Japan’s top draw, though he wasn’t necessarily presented that way. Despite being the flashiest and most innovative, he still took a backseat to Hashimoto, whose aura as a legitimate tough guy made him better suited for the role of stalwart company ace defending the company from outsiders. Muto also had to contend with Chono having arguably more inherent popularity as he exuded that sort of New World Order cool heel-charisma that made him likeable even when he was portraying a heel.

Bad News Allen Coage talked about Muto on his old website: “To me, from the new generation of wrestlers, developed by New Japan, he [Keiji Muto] was the most talented and charismatic. After Mr. Inoki left wrestling to go into politics, I thought they should have given him the big push. I felt he could have been Japan’s Next big star but the company went in a different direction. He is a great wrestler and a great talent.”

Yet Muto stayed consistent. By 1999, he had spent almost a full either main-eventing shows or being in the top three or four matches on NJPW’s biggest cards. He also had plenty of accolades to show for his effort: three long and successful reigns as IWGP Heavyweight Champion, one reign as NWA World Heavyweight Champion, five reigns as IWGP Tag Team Champion, multiple tournament wins, and a bevy of great matches under his belt against opponents like the Steiner Brothers, Jushin Liger, Big Van Vader, Hiroshi Hase, Genichiro Tenryu, and, of course, Chono. And by wrestling as both Muto and Muta, he managed to split his time between wrestling the ‘pure’ New Japan strong style matches and the more gimmicky violent bloodbaths and other hardcore matches without his reputation being tarnished since Muta stayed to the gimmicked stuff and Muto wrestled the more demanding realism-focused core NJPW style.

But as the 20th century drew to a close, Muto found himself at a crossroads. One path would’ve led him to retirement, and few would blame him if he chose that one. By 1999, he had been wrestling for 15 years and doing moonsault and other highly acrobatic moves had taken their toll on his body. But instead of choosing that path, Muto took the other one, which saw him continue wrestling… for another 24 years.

In 2001, Muto had arguably the biggest career renaissance in modern times. He changed his look completely: gone was the clean-shaven, wavy-haired babyface with bright neon orange wrestling trunks. In his place was a brooding bald man with a goatee and long tights with complex patterns on them. His wrestling style changed as well; to prolong his career and put less strain on his already shot knees, Muto build his matches in a way that combined classic ring psychology with a 5 Moves of Doom practicality. Most Muto matches saw him spam dropkicks to his opponents’ knees, dragon screw leg whips, and the odd amateur takedown, before applying the figure-four leglock. Muto went full speed ahead with the less-is-more philosophy and had wrestled in a way that saw him destroy his opponent’s legs before softening them up for his finisher. But it wasn’t the moonsault that Muto won most of his matches with; it was his new finisher, the Shining Wizard, which has become arguably the most copied move in modern times.

Muto’s change in look and wrestling style was also marked by a massive change in environment. His 2001 renaissance took place at the same time as Japan’s wrestling landscape was recovering from a bombshell of a transformation. After Mitsuharu Misawa led most of All Japan’s native roster on an exodus to his newly-formed Pro Wrestling NOAH, AJPW was left with what barely qualified as a skeleton crew. Yet All Japan still had the legendary Toshiaki Kawada, and he – as an AJPW representative – helped keep All Japan afloat in 2000 and 2001 by working big cross-promotional matches with New Japan.

But when it was over, Muto shocked the world by defecting from New Japan to All Japan. Unhappy with Antonio Inoki’s continued focus on his puro/MMA hybrid, Muto jumped ship to AJPW and, with the help of Kawada, Satoshi Kojima, and Genichiro Tenryu, Muto saved a Japanese wrestling institution from closing its doors forever.

But the 2000s was not all sunshine and roses for Muto. As Jonathon Foye covered in his book The Muto Years, Muto struggled to balance wrestling actively with managing and running an entire company. While the company had a decent core of big names, they were few and far between. This put pressure dual pressure on Muto, both as a wrestler and as a promoter. And while Muto became the man in charge after he bought Motoko Baba’s majority share of the company, it was really Muta who ruled All Japan as the company embarked in a strange direction that emphasized entertainment over the classic AJPW style.

Muto did his best to try and improve AJPW’s situation by trying to make the company as open for business as possible. He achieved some mild success, which included a long reign for Toshiaki Kawada, a huge cross-promotional match between himself and Misawa in 2004, and the crowning of Kojima as the new Triple Crown Champion in 2005. At the same time, with each passing year it became clear that Muto’s business and creative decisions weren’t translating into either new fans or happy established ones. Whether it was a departure from the classic King’s Road style, a greater emphasis on characters and gimmicks, or an inability to create compelling stars that could compete with the talent in New Japan or NOAH, Muto’s decisions slowly chipped away at All Japan as his continued efforts in the ring chipped away at his body.

Whether it was that unyielding strong style-inspired tenacity or sheer stubbornness, Muto refused to give up. Even if he had to pull the weight of several men, that’s what he did if it meant helping All Japan in some way. That led to Muto wrestling all over the world and working for several different promotions at the same time, including a one-off tag match for Ring of Honor in 2003. He also spent part of 2008 as a dual world champion.

Shinsuke Nakamura faced Muto, and wrote about it in his book, King of Strong Style: 1980-2014. “Fighting for the first time then, I really felt how huge he was. And then that distinctive pause,” noted Nakamura. “I think there was also the fact that I was young, but from the perspective of his opponent, the sense of space he brings into play caused me an incredible amount of stress.”

Nakamura quoted Riki Choshu once saying, “You can drink a cup of coffee when you’re fighting Keiji.” To Nakamura, that “meant that Mutoh didn’t match his own rhythm with the pace of the match.”

But even as his business ventures struggled or failed, his in-ring genius was still there. Nowhere was this more obvious than at NJPW’s Wrestle Kingdom III show when he wrestled his pupil Hiroshi Tanahashi in the main event. And despite being the wise old wrestling master both in gimmick and in terms of experience, the student beat the master. With Tanahashi’s win, New Japan turned its fortunes around and began an upward climb that only halted when the COVID-19 pandemic forced promotions around the world to close their doors.

In an ironic twist, the same wrestler exodus that brought Muto into All Japan also led him out. In 2011, All Japan faced a major scandal after a backstage fight between two wrestlers left one of them severely injured. The bad press following the incident and following Muto’s initial reaction to it led to him resigning from his position as All Japan’s president. He continued to wrestle for the company until he and his partners sold their shares of All Japan stock to an IT company. And when the president of that company fired Muto’s longtime friend and right-hand man, Masayuki Uchida, Muto left All Japan as well and took several wrestlers to form Wrestle-1.

Michael Majalahti who wrestled as “Starbuck” fought Muto at that time, and wrote about it on Facebook. “I had the honor of facing Muto in 2011 in Tokyo, as we had a six-man tag where I started the match with him. In the dressing room prior, Muto looked at me from his chair, then looked to his NJPW class of 1984 comrade and my good friend Akira Nogami, asking him ‘How is HE?’, looking directly at me. Akira responded, ‘European style, very good!’ to which Muto replied, ‘Ok, you and me, we start.’ We wrestled on the fly, move and countermove, hold for hold, old-school style before an appreciative Korakuen Hall audience. It was one of the most prolific moments of my wrestling career, and one that I will forever cherish.”

Unfortunately, there isn’t much to discuss about Wrestle-1. It wasn’t anything like the NOAH exodus; there were few big names involved (aside from Muto himself), it didn’t fit any particular niche or cater to any specific wrestling audience, and the market was way more saturated to begin with. With its only big moment featuring Muto hitting the final moonsault of his career, Wrestle-1 closed completely in April 2020, becoming one of many businesses to shut down permanently due to the COVID pandemic.

But even if Wrestle-1 was gone, Muto wasn’t. He signed with NOAH in 2020 and stayed there until his very last match. And just to prove how tenacious/stubborn he was, Muto won the GHC Heavyweight Championship in February 2021, at age 58. Even as surgeries mounted and his mobility became more limited, Muto was still able to extend his career longer and longer. He stuck to his formula rigidly; but considering that he managed to extend his career by more than two decades with it, said formula clearly worked.

But not even Muta could wrestle forever. The past several years have seen him wrestle fewer and fewer matches. In 2021 he wrestled only 30 matches all year. In 2022, that number dropped to 12. In both cases, most matches were tag matches and he didn’t have to do as much. But in 2023, the pressure re-emerged when he announced his actual retirement. Determined to leave with a bang, Muto embarked on a grand retirement tour that saw him tie up some loose ends, so to speak. He had one final match alongside Sting, the man that made Muta famous decades earlier.

He wrestled Nakamura one last time, with Nakamura getting revenge for beating him for the IWGP Heavyweight Championship back in 2008.

And while he wrestled all over the world and faced a wide range of opponents, it was fitting to see things come full circle on his retirement show. After losing to Tetsuya Naito in his “official” retirement match, Muto announced one final surprise: another last-minute singles match between himself and the man he defeated in his first match, Masahiro Chono, in what was also Chono’s official retirement as well.

With Muto’s in-ring career over, his legacy will be one of immense impact in the ring but less so outside the ring. There’s no denying that he was innovative and creative in the ring, to the point that countless wrestlers have adopted one or more of his signature moves. He is also a perfect case study in extending one’s in-ring career by adopting a more simplistic and limited move-set without sacrificing logic and psychology during a match.

In the ring, Muto will be remembered for being a dazzling performer that blended speed with incredible technical grace. He was a heavyweight that hit a snap moonsault like someone much smaller. His entrance attire and costumes made him look like a painted up Undertaker. He was clever and devious with his use of the Asian mist. He was so talented that he even managed to get a halfway passable match out of Bob Sapp, whose wrestling training bordered on nonexistent.

There is a legacy, many who were influenced by him, including Joe Doering. “He’s been really good to me. I’ve learned a ton from him. He’s good about giving me feedback on my matches and things I can do better, et cetera,” Doering once said of Muto. “Being in the same ring over and over with a legend like that, you have no choice but to grow as a performer and wrestler.”

At the same time, Muto’s ability as a booker and company manager is dubious at best. By his own admission, his mistakes “ruined two companies.” All Japan bounced back when Jun Akiyama took over in 2013 and is still alive while Muto’s second promotion, Wrestle-1, folded in 2020. And while he was able to help NOAH maintain some momentum, questions have risen as to whether he was right to go over the company’s younger stars.

In the end, Muto was actually a man of three faces, not two:

- There was Muto the wrestler who put on fantastic matches and influenced an entire generation of copycats.

- There was Muta, who brought presentation and gimmickry to a new level and made so much more out of the supernatural character he was given. In another wrestler’s hands the Muta gimmick would’ve failed but Keiji Muto made it work.

- Lastly, there’s Muto the businessman, and unfortunately, he just couldn’t measure up to the genius of those first two.

Keiji Muto spent the last decade of his career billing himself as “the pro-wrestling master” and had the word “genius” written on his tights. Sadly, things could’ve been much better for him if he stuck to the ring instead of trying to be a genius in the boardroom.

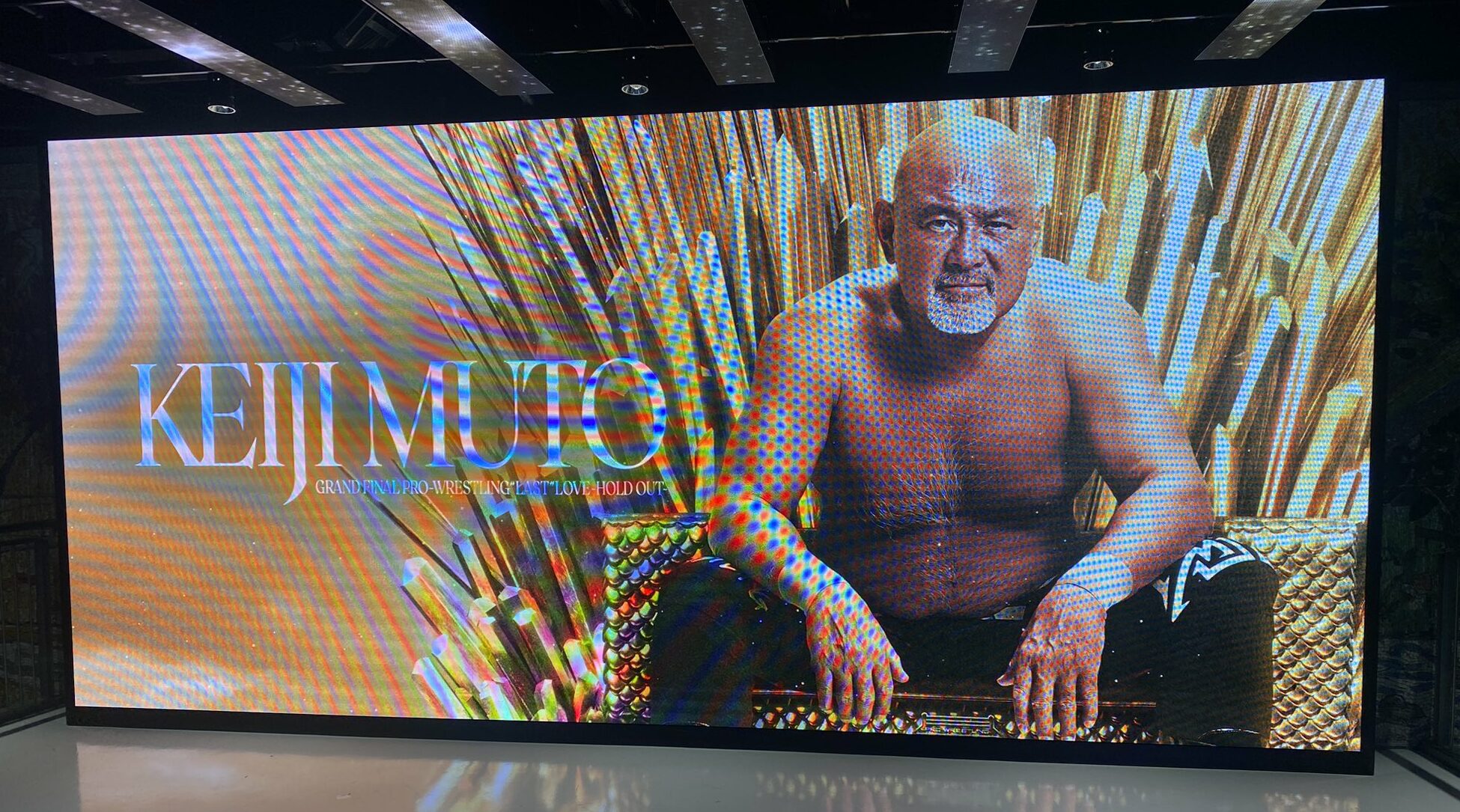

A Muto retirement electronic poster.

Recommended Muto/Muta matches:

- Great Muta vs. Antonio Inoki – Wrestling Dontaku 1994

- Great Muta vs. Hulk Hogan – Wrestling Dontaku 1993

- Keiji Muto vs. Big Van Vader – G1 Climax 1991

- Great Muta vs. Jushin “Thunder” Liger – October 20, 1996

- Great Muta vs. Sting – NWA Power Hour, September 1, 1989 or The Great American Bash 1989

- Keiji Muto vs. Genichiro Tenryu – AJPW, June 8, 2001

- Hiroshi Tanahashi & Kazuchika Okada vs. Kaito Kiyomiya & Keiji Muto – NJPW Wrestle Kingdom 16, Night Three

- Mitsuharu Misawa & Yoshinari Ogawa vs. Keiji Muto & Taiyo Kea – NOAH Departure 2004

- Keiji Muto vs. Toshiaki Kawada – April 14, 2001 or February 24, 2002

- Keiji Muto vs. Masahiro Chono – NJPW Violent Storm in Kokugikan – August 11, 1991

- Keiji Muto vs. Hiroshi Hase (the Muta Scale match) – December 14, 1992

- Keiji Muto & Hiroshi Hase vs. The Steiners – NJPW ’94 Battle Field In Tokyo Dome

- Keiji Muto vs. Hiroshi Tanahashi – NJPW Wrestle Kingdom III

TOP PHOTO: Keiji Muto says goodbye. Pro-Wrestling NOAH Twitter photo