With Keiji Muto being in wrestling news of late, fans of his have a golden opportunity to read about the man behind the gimmick. Much has already been said about Muto’s influence on pro wrestling itself as a wrestler, but what about his other work? What about his work as a promoter and company president? Thankfully, Jonathon Foye’s The Muto Years fills that void.

Taking off right where his first book Ganbaru ended, The Muto Years is an almost historical piece of wrestling posterity. It covers the period of Muto’s All Japan presidency (2002-13) and highlights Muto’s changes, successes, and failures as a man that balanced wrestling in AJPW and elsewhere with running a whole company.

For readers that still follow the wrestling business now, reading about Muto’s experiences will lead to interesting parallels with the modern wrestling landscape. For those unfamiliar with wrestling, the book will provide an interesting overview of how one of wrestling’s most revered in-ring innovators failed to bring that same ingenuity into the business side of wrestling.

Foye’s book is split into chapters that cover each of the Muto years one by one (with one exception being made for a multi-year highlight of Toshiaki Kawada’s 18-month reign as world champion). Each chapter/year serves to highlight the theme most consistent throughout Muto’s tenure: the idea of “the best of times and the worst of times.” No matter what Muto does that’s positive, there’s always something negative that either equals or outweighs his positive momentum, some of which is within his control and some not.

There are some great examples found throughout the book: All Japan did good business in 2002 but it came at the expense of the classic wrestling style of Giant Baba’s era. The company bounced back in 2004 in terms of fan interest and match quality but costs forced All Japan to book smaller venues. And what little momentum Muto made in creating new stars in 2009 was completely overshadowed by the death of his friend and fellow wrestling legend Mitsuharu Misawa. The book’s final chapters focus on a worsening situation for Muto as a backstage fight leads to his resignation as company president, followed by a change in company ownership that forces Muto to replicate the events of the 2000 split that led to his working for All Japan in the first place.

Foye’s book is an excellent piece of wrestling literature for 2022 because it couldn’t have come at a more opportune time. The lessons and experiences from Keiji Muto’s tenure as All Japan’s president and booker generate images of “regime change” not too far removed from what has happened in both WWE and AEW this year. Vince McMahon’s departure has been seen by many as the end of an era in WWE, not unlike the Babas’ association with All Japan. There were changes big and small that Muto made in All Japan that weren’t so different from the kinds of changes Triple H has since made in WWE or Tony Khan in AEW. Muto removed the giant poster of Giant Baba above the entrances early on. Triple H greenlit the use of the words “pro wrestling” that had been rumored to be verboten under McMahon. Triple H has done away with certain PPV concepts popular under his predecessor. Muto toyed with removing established tournaments if they didn’t draw. A backstage fight caused a scandal in All Japan and something similar has mired AEW in a fog for months, with any good news being overshadowed by any rumors and criticism towards AEW management relating to that fateful September incident.

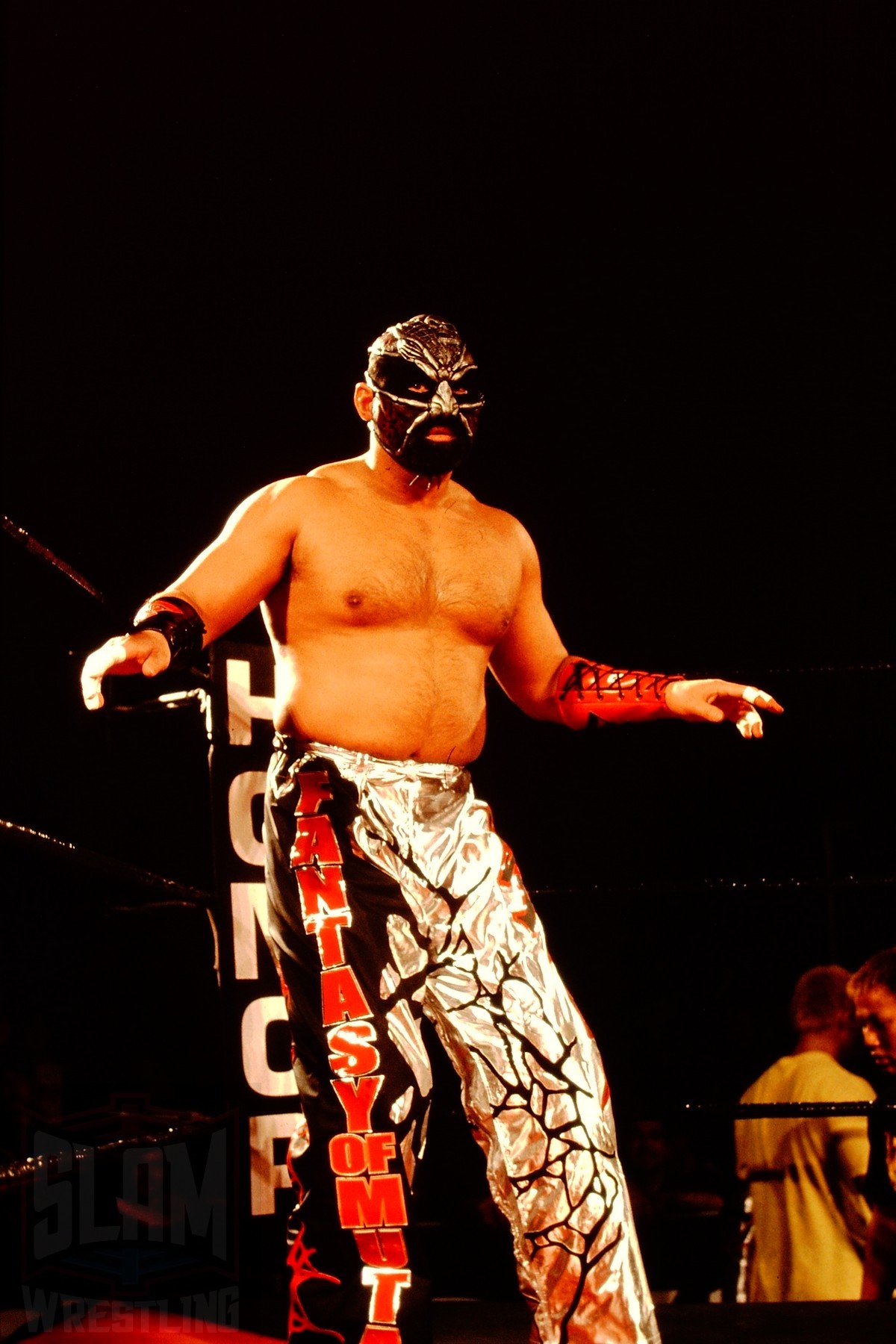

The Great Muta in Ring of Honor. Photo by George Tahinos, georgetahinos.smugmug.com

Perhaps the only key difference between WWE and AEW and Muto’s All Japan concerns access to money. Neither WWE nor AEW have been/are in a position where money is tight and finding business partners to serve as sponsors is a struggle. But Muto found himself in that position many times throughout the 2000s, to the point that he was forced to make some questionable business partners such as Dream Stage Entertainment and a Japanese porn company. But this added layer of pressure on Muto makes his struggle to keep All Japan going all the more compelling, in spite of the failures that seem to come up year after year.

The book provides many examples of Muto’s experiments and how they were perceived. It brought to the forefront an important dilemma that any wrestling/entertainment promoter should ask: whether to appeal to an established fanbase that knows what it wants and is resistant to change, or to expand and diversify the product to appeal to a wider audience. Muto’s various projects and booking philosophies aimed at achieving the latter, but as Foye’s book highlights, his biggest successes were related to the former. Muto’s wrestling/MMA hybrid produced alongside DSE (the owners of PRIDE) failed. His more gimmicky ideas like The Voodoo Murders and their Russo-style cheap interference finishes turned fans away. His attempts at balancing “defensive” wrestling (keeping the old stuff) with “offensive wrestling” (pushing new ideas) often saw him favor offense way more than defense. With each passing year/chapter, Foye highlights another piece of the past gone: Giant Baba’s image, his widow Motoko’s involvement, Stan Hansen’s removal as chair of the company’s title governing body, and the eventual departures of company mainstays Toshiaki Kawada and referee Kyohei Wada. By the time Muto leaves in 2013, All Japan barely resembles its King’s Road golden age.

Really, the only major successes Muto had while booking All Japan were Toshiaki Kawada’s 18-month world title reign, Kawada passing the torch to Satoshi Kojima and the successful rise of a wrestler named SUWAMA. And those creative directions were built on the classical King’s Road foundations that Muto was simply preserving.

The book also points out how wrestling’s history appears to be cyclical and filled with almost ironic twists and turns. Some of Muto’s earliest partnership endeavors led to All Japan booking MMA fighters on his shows. And it was this animus towards wrestling/MMA hybrid contests that caused Muto to defect from New Japan in the first place. It seems that no-one in the pro wrestling world could escape the shadow that MMA cast over the combat sports world in Japan during the 2000s.

Muto is praised by his peers for being an in-ring visionary, but the man himself admits that his management style “ruined two companies” in AJPW and Wrestle-1. This view is bolstered by several sources and interviews conducted for this book. These include: multiple editions of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, Stan Hansen’s autobiography The Last Outlaw, several interviews with Japanese wrestling journalist Fumi Saito and puro blogger HISAME, as well as journalists and commentators from around the world, including Toronto’s own WH Park and yours truly.

Jonathon Foye

If there were two lessons to learn from Foye’s book, it’s these. First, a pro wrestler can’t be expected to run an entire company while also maintaining the rigorous schedule needed to maintain ring shape. Muto’s split responsibilities caused him to struggle in both areas as the years went on, causing his great matches to become rarer and his business dealings to struggle. But he wasn’t alone in that struggle; Foye makes an excellent point to note that Mitsuharu Misawa did the same thing and he, too, struggle to live up to lofty expectations while balancing dual responsibilities. Even when Muto lost enough weight to compete in the junior heavyweight division for a short time, that didn’t translate into much upward momentum for the company, even if it added some novelty to Muto’s matches.

Secondly, change isn’t always good. Muto came into All Japan and promised to make minimal changes at first. That proved to be false. With each passing year, Muto made more changes and proposed additional ones, all of which caused All Japan’s fanbase to shrink. The fans wanted classic All Japan, and for a decade they still got it, albeit in very small doses. The book contains a postscript list of hidden gem matches, with most of them being either from Kawada’s reign or involving more classic King’s Road-style wrestlers. Foye’s interviews with Saito and Hisame gives readers insight into fans’ mindsets at the time and how Muto’s attempts at bringing in new viewers came at the expense of driving established ones away. One of the final chapters includes an epilogue of sorts that explains how Jun Akiyama took over All Japan after Muto and brought it back to its Baba and Four Pillars-inspired roots and is now thriving (relatively-speaking) while Muto’s Wrestle-1 has folded. At the end of the day, taking too much away from one’s core audience is likely to leave a business in dire straits long-term. Loyal AJPW fans bowed out year after year, while Muto’s gains with his bold new style didn’t translate into long-term financial success, especially since a similar project was underway with Tajiri in HUSTLE.

This isn’t just a book about wrestling; it’s a book about culture and people. It’s about people from different worldviews trying to work together in new environments but their interrelationships end up more jagged than smooth. Many people saw Muto’s changes to All Japan as him trying to fit a square peg in a round hole. He achieved some success but it came at very high costs; Foye noted several times that Muto had to spend millions of his own personal fortune to keep AJPW alive before it was sold to an IT firm.

So while Keiji Muto’s 2023 retirement is fast approaching and fans discuss his accomplishments, it’s important to take a look at Foye’s book here. Much has already been written about Muto’s genius in the ring, including in North America as The Great Muta. He’s quite possibly the most emulated and copied Japanese wrestler ever. But it wouldn’t be fair to judge such an important wrestling figure without taking a careful look at his business acumen and what he achieved outside the confines of the squared circle. Foye’s book does just that and does most of the heavy lifting for the reader in terms of aggregating information and explaining it in neutral terms. All the reader has left to do is judge for themselves as to whether Muto’s genius really expanded beyond the squared circle.

RELATED LINKS

- Order The Muta Years from Amazon.com or Amazon.ca

- SlamWrestling Master Book List