Jack Pfefer knew big men. In fact, he practically invented the trope in the mid-1930s after taking Martin Levy, a down-and-out 600-pound man from Boston eking a living out as a circus freak, and turning him into “The Blimp,” a freak of another variety.

Of course, The Blimp was actually Pfefer’s answer to “Man Mountain Dean,” a super-heavyweight finding considerable success with Lou Daro in California. Butt Dean, real name Frank Leavitt, was a military veteran and former football player who could hold his own with the best in the ring, whereas Levy was, as one sports editor put it: “In terms of wrestling ability, he’s very fat.”

But ask Pfefer, and he’d happily tell you, “No living wrestler today can outdraw the human Blimp.”

He continued pushing big wrestlers throughout the years, including “Mighty Jumbo,” “Happy Humphrey,” and even a “Lady Blimp,” amongst others.

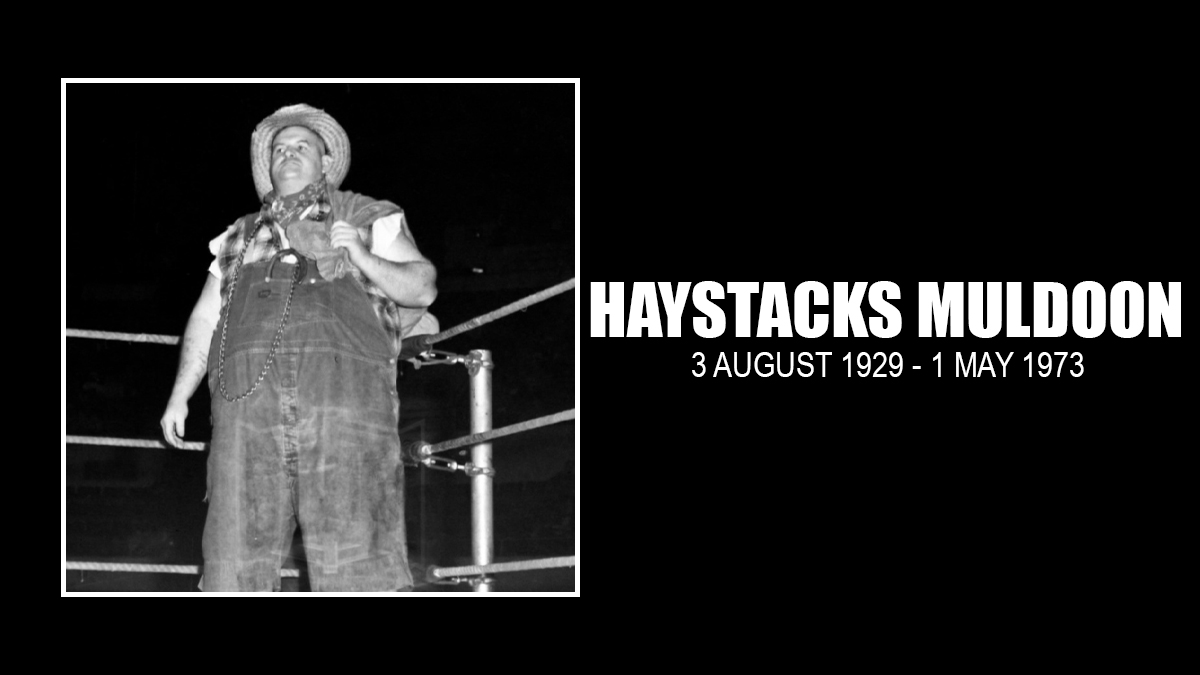

Edward J. Touhey Jr. was another in that line, hooking up with the aged Pfefer in 1959. Billed as a 475-pound good ol’ boy from Arkansas, Touhey became “Haystacks Muldoon,” Pfefer’s answer to Haystacks Calhoun, the superheavyweight of the moment and a major star throughout the country.

But Muldoon wasn’t from Arkansas, a Southerner, or even a real farmer. Rather, he was just an Irish kid from New York looking to make a name for himself in wrestling.

This is his story.

Early Life

While Arkansas was his billed home, the reality for Edward Touhey Jr. was far less exotic. Born on August 3, 1929, to Irish immigrants Edward Sr. and Mary Touhey, young Edward was considered a quiet and unassuming child by his mother.

Very little is known of Touhey’s earliest years. He may be related to Brooklyn’s Edward C. Touhey, a former football player and later a locally famous long-distance walker, who died around the time of Ed Jr.’s youth.

The family grew up in Howard Beach, Queens, New York, at that time a sleepy fishing village just nine miles as the crow flies from the hustle and bustle of Manhattan. The small peninsula, built on reclaimed land by the Aqueduct Racetrack, was working class through and through, the home of the legendary singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie, and a far cry from the upscale seaside village it has become in the proceeding century.

During the Great Depression, the area, like many other New York neighborhoods, suffered greatly, and many residents sought aid from the local charity of Saint Barnabas Church. It is likely that Edward Touhey Sr. was one of those residents in need of assistance. The family’s patriarch, who had previously worked as a construction worker operating a steamroller, found himself unemployed as the Depression unfolded, which was particularly challenging with a young family of four children to support.

As the oldest of four children, Edward Touhey followed the path of many working-class youths of his generation and joined the military after completing his education at a Queens parochial school and a local vocational school.

In the Army he found some success in the military, eventually reaching the rank of private first class. In January 1948, he re-enlisted for another 18-month contract. By May 3, 1949, he was just weeks away from being discharged when he became internationally famous for a brawl with Russian officers in Vienna, Austria.

I Saw Red

“A 19-year-old American GI beat up seven Russian officers in the lobby of their hotel yesterday before he was dragged away by 12 American military policemen and an Army doctor,” read the story in the next day’s St. Petersburg Times.

But if the story sounds too incredible to be true, the reality is even more chaotically amazing.

Private First Class Edward Touhey, who was serving in Austria as a member of the 109th Military Police Battalion, had recently been discharged from a military hospital and decided to familiarize himself once again with his European surroundings.

“I had spent a month in the hospital with athlete’s foot,” he’d later tell Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Hal Boyle in his August 1954 column that was syndicated nationwide. “When I got out, I stopped at a bar. I drank a bottle of cognac — maybe more. I must have drunk it too fast because when I left the bar to go to the barracks, I got on the wrong streetcar and fell asleep. When I woke I saw I was in the international zone and got off.

“I was feeling bad and leaned against the wall of the Imperial Hotel, holding my stomach. It was a Russian hotel. A Russian officer and two armed sentries came out and made me go into the hotel. The officer called me a spy and said I had been taking pictures of Soviet personnel. Then they stood me against a wall and forcibly searched me. They were pretty rough.”

The commotion began at the prestigious Grand Hotel in the city’s International Quarter, home to the occupation forces in post-war Austria when the Russians accused a drunk American serviceman of deliberately taking photos of officers. However, Touhey said the Soviets quickly moved him to the Imperial Hotel.

The hotel, an icon of Viennese style, was originally Palais Württemberg, the neo-classical Palace of Duke Philipp of Württemberg. In the new post-war realities, however, the building served as a billet for Soviet officers, and Touhey was dragged in for questioning. He continued the story:

The Russian officer said he still thought I was a spy, even though he saw I didn’t have any camera. He said I must have handed the camera to someone passing by. Then he said he was going to turn me over to the American military police. I got scared. I thought it was a trick that he would take me to the Russian zone, and I’d never get back. I made a beeline for the door. A sentry put his bayonet to my stomach. I knocked it away, and the Russian officer grabbed me from behind.

That’s when I went berserk. I saw red.

From there, Touhey purportedly turned and kneed the officer, who cried out in agony, with additional Russian soldiers then pouring in from every side. Touhey fought back using fists and an iron chair, mowing them down one by one before breaking free and crashing through a glass door. However, his freedom was short-lived, with another wave of Russian reinforcements finally grounded him.

American Idiot

That’s Touhey’s version of events, though the US Army had a different viewpoint. During the subsequent court-martial, Col. William Leibel outlined the following sequence of events:

Touhey, who had been drinking, engaged in a fight with a Russian sentry outside Vienna’s Grand Hotel in the city’s International District. Following this altercation, Touhey crossed the street to the Imperial Hotel, where he punched another officer at the door. He then proceeded to enter the lobby and launch attacks on approximately 8 to 12 more Russians, one after another. Eventually, he chased a Russian colonel across the lobby, wielding a wrought iron chair, until a group of American military police and a doctor subdued him.

If the attack on Russian military personnel was shocking and astonishing (yet still a very “America, hell ya!” moment), it wasn’t entirely unexpected by those who knew him.

Touhey, known as the “fighting Irishman from Queens” in the press, was exposed as a staunch adversary of all things Russia following the attack. He was apprehended and later imprisoned by Army officials in Salzburg. His arrest also prompted a psychological evaluation. “In simple language, he hated them,” stated his mother, Mary, who noted that her son had expressed his disdain for the Russians in his recent correspondence.

“The Russians put the whole blame on me,” Touhey recalled sorrowfully to Boyle. “They said I’d fractured a colonel’s skull and broken two guys’ jaws.”

Looking back at the situation some five years later, Edward admitted he made one serious error: “I shouldn’t have drunk that cognac so fast.”

The incident marked Touhey’s first — but not last — brush with notoriety.

To begin with, the US Army was compelled to issue a formal apology to the Soviet government. Then, President Truman issued an extra apology to the Russians, hoping to smooth over the suddenly extra-strained relations as the Cold War began to heat up. Finally, Touhey faced a court-martial in Salzburg, resulting in a sentence of six months of suspended hard labor, a $300 fine, and a dishonorable discharge “for the good of the military” on August 10, 1949, after serving three years in the service.

Touhey also had a tattoo on his right forearm that read “Vienna, Austria, May 3, 1949,” as a physical reminder of the event.

However, there were also moments of fame. Gossip columnist and radio news commentator Walter Winchell gave Touhey a shout-out, starting his broadcast one evening with “I am in love tonight with a wonderful GI.” And, most notably, Touhey appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, an appearance that would eventually steer him towards the ring.

“All the publicity was what started me off in professional sports,” Touhey would tell the St. Petersburg Times, noting that his initial foray into the ring was actually as a heavyweight boxer under the tutelage of Jimmy Dixon.

Down and Out

Of course, reality wasn’t so clear cut.

The truth was that the years following his discharge were difficult for Touhey. Initially, he struggled to find employment back home in New York, which forced the 21-year-old Irishman to change his location but not his attitude.

On May 13, 1950, Touhey arrived in Corpus Christi, Texas, looking to start anew. Realizing that his job prospects back home were limited, he saw Texas as the ideal next step in his life. He moved into the YMCA and alerted the press that he was looking for work, no matter what it entailed.

Touhey’s true reason for migrating to Texas was his hope of finding a job in the fishing industry, something he picked up from his youth on Howard Beach and a passion he indulged in his entire life.

Unfortunately, Touhey’s demons, including his propensity for binge drinking and resulting aggression, did not abide by geographic changes. In November 1950, he was again in jail, this time as a civilian. While visiting the Home Road bar, Touhey decided to showcase his strength to other patrons by attempting to push a bus. However, alcohol, the patron saint of misguided confidence, intervened. Touhey ended up in a ditch on the roadside.

Rather than taking his comical stumbling in good nature, Touhey responded by smashing car windows with his fists and attacking up to four bystanders, including a 17-year-old named Charles James, whom local authorities charged Touhey with assaulting. He was charged with disturbing the peace, drunk and disorderly conduct, and conducting himself in a lewd manner.

Unemployed and therefore unable to afford his $381 bond, Touhey decided to spend his time in jail at a rate of $3 per day. If he served the full sentence, he would spend a total of 127 days in jail.

The proceeding years were equally as challenging, with Touhey again unsuccessful at finding gainful employment before finding steady work at a steel mill. Eventually, that security was stripped after a slate of layoffs at the mill in 1954, with the then 350-pound Touhey looking to use the remaining notoriety he had to help establish himself in the boxing world.

At the same time, he turned to the press to continue to tell his side of the story, with the ultimate goal still either an honorable discharge or reinstatement in the Army.

“In three years with the Army, I never went AWOL once,” he told Boyle in his August 1954 column that received considerable coverage across the country. “I understand they were even considering giving me a good conduct ribbon at the time this whole thing happened. Either the Army should take me back into the service or give me an honorable discharge.”

Haystacks Muldoon: A Bumpkin Is Born

His Texas escape turned out to be a dead end, and by the end of the decade, Touhey was back on the New York coast, again bouncing around through a series of semi-regular jobs. It was one such gig, a Good Humor ice cream man, where a fateful meeting with Jack Pfefer would provide him with a new lease on life and a new beginning as an unlikely star in professional wrestling. Pfefer, a wrestling promoter known for his unconventional troupe. recognized the potential in Touhey’s impressive size, around 450 pounds. Despite that weight, Touhey still showcased some of the boxing footwork he had learned from Jimmy Dixon, making him an agile and enormous grappler.

Pfefer combined Touhey’s straightforward and simple Americana charm with the persona of a farm boy from Arkansas, creating “Haystacks Muldoon” as a response to the popular hillbilly wrestler Haystacks Calhoun, who drew large crowds across the United States.

Muldoon’s appearance perfectly matched the expectations of a hillbilly character, complete with denim overalls, a straw hat, and bare feet — a trend popularized by previous stars like Farmer Marlin, one of the most successful hillbillies of the era. To conceal the folds of his large frame, Muldoon wore a plaid or white undershirt and added a horseshoe chain around his neck for good luck, embracing his identity as a good ol’ boy from Arkansas.

With Muldoon, Pfefer secured exclusive rights, complete control, and the ability to pay the wrestler a low rate while still profiting from regional promoters.

While Calhoun undoubtedly inspired Muldoon, he was just one of many obese wrestlers promoted by Pfefer. Pfefer specialized in promoting freaks, especially when it came to attracting media attention. As Washington Post journalist Shirley Povich described in 1941, “Pfefer’s promotional technique doesn’t rely solely on the action in the ring. The focus is on showcasing freaks and providing entertainment, and if Pfefer can get even one picture of one of his freaks in the newspapers before a show, its success is almost guaranteed. His shows are like a traveling circus.”

Pfefer bet big on Muldoon in 1960 as he and Boston promoter Tony Santos aimed to capitalize on their new position at the Boston Garden and a budding relationship with Jim Barnett and his burgeoning AWA, a direct competitor to the NWA and Pfefer’s chance to get back in the big time.

Touhey was trained at Santos’ wrestling school at his wrestling offices in the Boston Arena Annex. The school was one of the few publicly available wrestling schools, a unique selling point that attracted a slew of hopeful trainees, not least of which the great Les Thatcher.

The school was a crash course in the basics of pro wrestling, including instruction from Santos’ son, Gene (The Great Kilroy, Zanzibar Firpo of the Fabulous Zangaroos, Gene Dundee, and Flash Monroe amongst his many monikers), and a firm seasoning by Santos’ policemen, including “Cowboy” Frankie Hill and Alex Medina.

Santos’ school produced plenty of impressive talent, including many women’s grapplers trained by world champ Alma Mills. But the newly christened Muldoon was no ring general; rather, he was a semi-agile big man who relied on his heft to do the work.

Muldoon made his debut in Rhode Island and quickly gained popularity throughout New England, often competing in handicap matches against two opponents, showcasing his friendly and imposing wrestling style while having fun in the process.

“I consider myself a comic wrestler,” Muldoon told the press in 1963. “If you can’t laugh while watching me in the ring, then something must be wrong with me. I’ve always been a favorite among kids, and that’s why I try to bring some humor to my performances.”

That comedic success came from Touhey’s uncensored, down-home persona. But while that country boy approach won the hearts of fans, it often came at the cost of ruffling feathers with the local elites.

Just ask Cardinal Cushing.

Richard Cushing served the Catholics of New England as the Archbishop of Boston from 1944 to 1958 and was raised to the rank of Cardinal. He skillfully navigated the religious and cultural minefields of Roman Catholic and Protestant Boston, gaining immense social clout among the city’s elite.

The Cardinal and Paul Bowser had partnered for an annual Cardinal Cushing Christmas Fund wrestling card at the Garden. Tony Santos and his business partner (and the new director of wrestling at the Garden, Jack Pfefer), hoping to jump into the big time with their new push into Boston, were eager to keep the partnership alive.

In the buildup to the December 16, 1960, card, Santos visited the Cardinal’s home with a few of his stars for a photoshoot. According to Thatcher, who broke in Boston in 1960 and was friends with Touhey during the period, Santos came with his son, Gene, two of his prize talents, Alma Mills and Frank Scarpa, and Pfefer’s latest star, Muldoon.

The Cardinal and Touhey immediately hit it off, enjoying a friendly chat until a housekeeper quickly ushered the Cardinal away to change into his vestments, the press due at any moment.

Cardinal Cushing, now adorned in his ecclesiastical splendor, returned to his conversation with the friendly farmer, excusing himself for his costume change and jokingly questioning Muldoon about his trademark horseshoe and its significance.

“It’s my gimmick, just like yours,” Haystacks responded, pointing to the Cardinal’s vestments.

According to Thatcher, recounting one of his favorite stories of that early year, Tony Santos nearly fainted from shock.

But life in Boston wasn’t all about rubbing elbows with the city’s finest. In fact, the reality was far more gritty, and that extended to the place Santos’ wrestlers called home.

The boarding house at 72 Westland Street, a stone’s throw from both the Boston Symphony Hall and Boston Arena, where Santos was based, was perfect for the wrestlers working under the thumb of the city’s newest wrestling kingpin in that it was close to the action — and cheap.

For just $10 per week, the residents (who also included a fair number of unsavory elements of the city’s underbelly) could enjoy a shared bathroom and sumptuous furnishings, including a bed, a table, and a small black-and-white television.

But where housemates like Thatcher, Ronnie Dupree, and Pat Patterson immersed themselves fully into their new wrestling world, Touhey never seems to have fallen in love with the sport.

Like his previous attempt at boxing, his wrestling move was entirely geared not toward the love of sport but the safe, steady, and lucrative paychecks that had eluded him for much of his adult life.

What’s clear, however, is that Touhey saw his new persona as a chance to reset his life. Despite the brief notoriety he had earned some 12 years prior, Touhey never spoke about his military service with fellow wrestlers, instead focusing on topics closer to his heart — like fishing.

According to Thatcher, who began training with Santos in 1960 and lived at 72 Westland with Touhey and a score of other wrestlers, including Dupree, Patterson, Jimmy “Flash” Thomas, and others, wrestling wasn’t a passion for Touhey, but rather a steady job with good pay.

Muldoon’s biggest in-ring opportunities came at the Boston Garden, where Pfefer hoped he could revitalize the talent pool for the mat shows. This was especially important after Eddie Quinn withdrew from the state and perennial favorites like Don Eagle, Killer Kowalski, Bearcat Wright, and Pepper Gomez left around the same time.

In 1961, Muldoon also played a key role in Pfefer’s short-lived opposition battle against Barnett in Denver. Pfefer promoted Muldoon, along with other similar-sounding wrestlers like Big Daddy Siki, Big Splash Humphrey, and Ali Singh, to his impressive roster.

And while the results may not have been outstanding, Muldoon consistently drew crowds in New England, Alabama, Ontario, the Midwest, West Texas, and even California, where he headlined at the Olympic Auditorium.

He even appeared at Madison Square Garden on October 24, 1960, defeating Larry Simon, the future “Professor” Boris Malenko, on the undercard of the Bruno Sammartino/Antonino Rocca main event. The card also included the Bavarian Boys, Wildman Fargo, and Ricki Starr — a testament to Pfefer’s continued power in the Big Apple despite his move to Boston.

In the ultimate irony, the Garden card also featured a young Karl Gotch working under the name “Karl Krauser,” a rip-off of a Pfefer original: Karol Krauser, later Karol Kalmikoff.

As a Pfefer talent, Muldoon also incorporated a fair share of PR into his bouts, including issuing challenges for wrestlers to see if they could slam the mammoth 475 pounds “Ozark Mountaineer.”

Perhaps the most famous example of the body slam challenge was when Don Leo Jonathan, the Mormon Giant, finally scooped up the giant Muldoon and slammed him to the mat — after plenty of theatrics.

According to Dr. Bob Bryla, an eyewitness to the feat in Utica, NY, Jonathan tried unsuccessfully several times before retreating into a corner to contemplate how to achieve the body slam.

“He finally did it, and the whole auditorium shook,” recalled Bryla.

But as with most things in pro wrestling, it wasn’t a one-time event but rather a gimmick run around the horn.

“Years later, I saw a tape of them doing the same act in Buffalo,” added Bryla, whose father served as a New York State Athletic Commission ringside physician during the period and often brought his young son to the shows.

But if Muldoon’s star was apparently rising, his own stupidity would quickly halt any momentum.

The 500-Pound Fraud

In March 1963, Touhey found a significant gap in his schedule and decided to vacation on Florida’s Gulf Coast. He settled in St. Petersburg Beach (now St. Pete’s Beach), a tourist trap of about 6,000 people at the time. Touhey quickly ingratiated himself with the local population and businesses, enjoying spending his earnings from his wrestling fame.

However, just one month later, Touhey’s world, along with his alter ego, Haystacks Muldoon, came crashing down. He was again in trouble with the law, this time as a fraudster on a truly grand scale.

The problem arose from the personal checks Touhey would sign and hand out to businesses like autographs to his young fans. Unfortunately, these checks, drawn from an unspecified Canadian bank, were immediately returned by the bank with a note stating that the account had been closed.

The account had been closed just weeks earlier, in February 1963, and Touhey was well aware of that fact.

Soon after his departure, the news (and charges) from local police flooded out.

Perhaps the most incredible charges were those at a local jewelry shop just two days before leaving the area. Touhey purchased two diamond rings from the store, both requiring significant alterations to fit his oversized digits. Valued at $10,000 and $3,170, respectively, and paid for with the same bad Canadian checks, the rings were worth an astonishing $135,000 in modern money — fraud on an almost unbelievable scale.

But the most damning act was Touhey’s fraud of a local restaurateur, whom he regularly fleeced during his time on St. Petersburg Beach. Eating at the same restaurant daily, Touhey lulled the owner into believing his biggest fan was a well-to-do wrestler living the high life on vacation.

According to Pinellas Sheriff’s Deputy Harold Glenn, Touhey, who was living his gimmick as a successful country boy, asked the restaurant owner to cash a $970 check so he could buy a used car. Then, the day before he left, Muldoon asked the restaurant owner to cash a second check for an additional $350.

In a seemingly generous gesture, Touhey, learning of the restaurant owner’s financial difficulties, decided to bestow some of his newly concocted wealth on the man. He wrote a check for $1,100 and advised the owner to “use as much as you need and save the rest till I come back next year,” Deputy Glenn reported to the Tampa Bay Times.

Additionally, the Pinellas County Sheriff’s Department charged Touhey with the following fraudulent transactions, all made by check:

- A gold coin, which he purchased from a local resident for $945, paying with a $1,000 check and requesting $55 back as cash.

- A gold watch, which required additional bands to fit his wrist. He paid with a $224 check.

- $550 in checks for his motel, including $300 for “reservations next year.”

All told, Touhey wrote worthless checks valued at $17,640 during his March vacation in St. Petersburg. Accounting for inflation, that sum is $181,000 ($246,000 CAD). With such an almost unfathomable level of fraud committed, authorities in Pinellas County issued an all-points bulletin for Touhey in early April, believing the rotund runaway was heading for Canada, the source of his rubber checks. The FBI wasn’t far behind, issuing a warrant for “unlawful flight to avoid prosecution.”

Fortunately, Touhey wasn’t running for the border. Rather, he was shifting his place in the sunshine, being tracked down to Belmar on the Jersey shore. He was arrested on May 23, and officers from Pinellas County made the trek to pick him up and deliver him to justice that Monday, May 27, 1963.

The Kid’s Favorite Fugitive

If Touhey ever intended to fight the charges, that prevention disappeared almost immediately. Instead, the 5-foot-10 inches, 500-pound behemoth adopted a conciliatory tone more akin to his Christian faith.

The superheavyweight was a popular subject in the Tampa press, which liked to recount the wrestler’s tall tales, including his Vienna brawl and the subsequent fallout.

The papers were especially quick to humanize Touhey, and he was more than happy to chat with anyone while he was in a local lockup awaiting trial. This allowed him to explain his story, his views on life, and his work as a role model for children. Even the officers of Pinellas County were won over by Touhey and Muldoon alike, with Deputy Glenn telling the Tampa BayTimes about the true impact he was having on the nation’s youth.

“Haystack won’t tell you this himself, but whenever he appeared in a city, he always went there a day early and visited the crippled children’s hospital,” said Glenn.

“And when I picked him up in New Jersey,” he added, “Haystack gave a little boy he had met the big chain and lucky horseshoe he always wore around his neck to make the lad feel better.”

Touhey’s commitment to his young fans was no gimmick. Long-time fan Bryla fondly remembers his interactions with the massive Muldoon in Utica, even after all these years.

“Haystack used to take a chair and sit in the back of the audience while the other matches were taking place,” Bryla recounted. “He would always have several kids my age around him, and he seemed to enjoy talking to them and kidding around.

“Once, he put one of us in a headlock and asked if it hurt. Whichever one of whichever one of us it was, Haystack asked if it hurt.

“The headlock recipient, possibly me, stated that it did not hurt, and I remember Haystack saying that he would never think of hurting any of us.”

Jail Bird

When the trial finally came, Touhey never contested the charges, telling Third Circuit Court Judge BJ Driver, “I know I done wrong, I don’t deserve to breathe the same as you do. I know I’m bad.”

His supposed excuse, that he began writing bad checks because of a lull in his bookings (and an undoubted decline in his finances) was pitiful but failed to elicit sympathy from the judge, despite what the press dubbed a “eloquent speech.”

“I couldn’t possibly give a man with your record probation. You are a public figure and have a strong influence on athletic youngsters. I have to be as strict with you as with anyone else.”

“Stricter,” Touhey responded before thanking Judge Driver and resuming his position amongst the other jail prisoners.

Edward Touhey Jr. was sent to federal prison to serve his six-month to five-year term, far away from the smiling faces of fans he was so accustomed to.

Recidivism, Country Style

Haystacks Muldoon eventually returned to the ring upon release, first in Hawaii for Al Karasick in late 1965. But not long after his return, he was arrested again, in Aberdeen, South Dakota, in November 1966, again charged with fraud, this time obtaining money or property under nefarious means.

The arrest listed Touhey as a Fort Lauderdale, Florida, resident and set his bail (which he posted immediately) at $1,000. Touhey again waived a preliminary hearing, apparently hoping to play the apologetic card again.

Unfortunately, there was no follow-up in the South Dakota press, but his prior criminal history and poor financial management (plus Muldoon’s inexplicable disappearance until 1967) make it likely he spent at least some time behind bars.

The Final Years of Haystacks Muldoon (and Edward Touhey)

It’s clear that the South Dakota charges didn’t significantly harm Touhey’s bookings after his possible release, as he once again began to appear for Pfefer and Santos in New England along with a wide array of eastern promoters like Nick Gulas in Tennessee, Pedro Martinez in Buffalo, Jim Crockett in the Carolinas, and Leroy McGuirk in Oklahoma, among others, in the following years, though the bloom was clearly off the rose when it came to singles contests, with Muldoon often facing off against former Santos alums like The Beast (John Yachetti) and Hans Schmidt, often on the losing end.

Perhaps his most significant run occurred in New England, where he resumed his role as the jolly giant. However, Santos’ control over Boston wrestling had faltered with the arrival of the WWWF, promoted by Abe Ford.

Harold Kaese, in the April 8, 1967 edition of the Boston Globe, criticized the state of Boston wrestling, stating:

If wrestling in Boston returned to the big leagues when 6300 fans recently paid to see Bruno Sammartino of Washington, D.C., one of several claimants to the world title, it was back in the minors last night.

The kind of action provided in these weekly shows is not enough to attract more than a relatively few who enjoy their belly laughs or are unbelievably naïve.

If Smasher Sloan was truly enduring such agony from the belly presses of Haystack Muldoon, he would deserve nothing less than the silver gall bladder.

But I never felt so self-conscious in my reporting career as when I tried to type this column on an empty bench in a nearly empty arena beside a ring in which muscular actors were performing…

It has been 13 years since anybody took wrestling seriously enough around here to use a typewriter at ringside.

Despite the declining crowds in New England, Touhey continued to find intermittent success in the wrestling rings of North America for the next five years, again with a heavy emphasis on handicap matches and tag team contests to hide his diminishing skills as his weight continued to climb.

His career eventually wound down in 1972, with his final appearances taking place in South Carolina and Upstate New York.

He passed away in Fort Lauderdale the following year, on May 1, 1973, at the age of 43, and was laid to rest at the Lauderdale Memorial Park cemetery.

Conclusion

Edward J. Touhey lived a life he would have never imagined in his wildest dreams during his youth in Queens. Instead of the life at sea he dreamed about while staring out over Jamaica Bay, he traveled the world with plenty of adventure.

He had single-handedly defeated the Soviet occupation force in Vienna but couldn’t get out of his own way.

Touhey was folksy, friendly, and his own worst enemy. His tendency to drink (and subsequently fight) often left him behind bars. And if that didn’t, his hobby of bank fraud would.

Despite his flaws, Touhey positively influenced those whom Haystacks Muldoon was most aimed at: the children. His visits to children’s hospitals and youth centers were as well-intentioned as they were received.

Bryla summed it up eloquently: “Haystack once said that you can build ships of gold and you can build ships of silver, but the best kind of ship to build is a friendship.”

Ultimately, while the rise of Haystacks Muldoon coincided with the terminal decline of his manager, Jack Pfefer, it’s clear the character was never meant to be that generational-type of wrestler remembered decades later like the man he mimicked, Haystacks Calhoun.

Edward Touhey Jr. was the reason why.