When Greg Oliver and I conceived of The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes & Icons in 2007, Ricki Starr was one of the guys we targeted from the beginning. At the time, Starr was more than 40 years removed from his heyday as a star in North American wrestling circles. But he had never told the story of how he used a pair of ballet slippers to ascend from lowly opening matches in Texas gyms to the top rank of pop culture superstardom.

Born Bernard Herman in St. Louis, Starr had a well-deserved reputation as the J.D. Salinger of wrestling; he achieved stunning success as a relatively young man and lived his life in comparative obscurity in London after retirement. “He disappeared off the face of the earth for a number of years,” said Exotic Adrian Street, who wrestled him in Europe and retains ties to the British wrestling community.

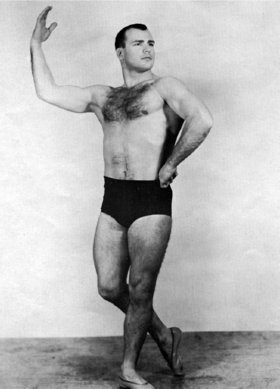

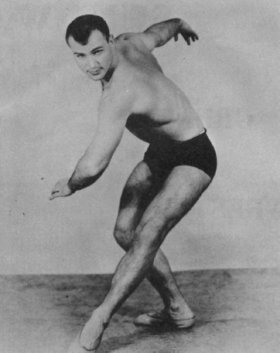

Ricki Starr. Photo courtesy Crowbar Press, www.crowbarpress.com

Our notebooks are brimming with interviews and observations from his relatives, high school friends, fellow ballet trainees, wrestlers, promoters, and others who encountered him during his life. A favorite is from George “Zebra Kid” Bollas: “Give Rickey Star my fondest, sexiest wishes. He’s so cute, I wouldn’t know if I should wrestle him or fu– him. Ha ha.” And we have a thick swath of correspondence from Starr to his manager Jack Pfefer that ranges from the mundane to the exotic to the erotic.

But despite years of our letters, emails, messages and the generous intercession of intermediaries, we whiffed on Starr. Street explained that Starr also rejected overtures from his fellow combatants; he had become a spiritualist who divorced himself from his past. “He was never right in the head, quite honestly,” Street quipped. In 2009, when an old classmate from Soldan-Blewett High School in St. Louis posted some information about him on the Internet, Starr asked him not to write about him any more. That part of his existence was concluded.

With Starr’s death after a brief illness Sept. 20 in London at 83, we’ll never get his life history, but that’s acceptable in a way. Our overriding goal in writing profiles for the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame series has been to explain who these wrestlers were, not just what they did, and Starr’s devout introspection was one of his identifying traits. As he observed in a 1967 interview, “There is something lacking in my makeup that prevents me from winning true and lasting friendships. I guess I sub-consciously feel that I have a hard enough time getting on with myself without inflicting ‘me’ on others.”

So remaining unanswered will be questions such as why Starr bolted to Great Britain for good in 1963 or how he got interested in ballet in the first place. Still, there’s a pretty extensive documentary record that tracks the development of Bernard Herman from the mat at the Young Men’s Hebrew Association in St. Louis to the stage of Mr. Ed, the TV show about a talking horse. As longtime Northeast promoter Willie Gilzenberg put it: “I don’t think there is a wrestler since Jimmy Londos who was able to crack as many outstanding magazines, TV interviews and bring out the best in audiences as Ricki has been able to.”

Starr was a natural fit for the combat arts; his father Joseph wrestled, boxed and refereed in Missouri and Illinois and was dubbed a “professional anguish artist” by the Alton (Ill.) Evening-Telegraph in 1937. Born in 1931, Bernard attended Soldan-Blewett High School in the Academy neighbourhood of St. Louis, leaving briefly in 1949 to work in the Kansas wheat fields so he could finance training as a boxer at Stillman’s Gym in New York. A few sessions with serious pros such as Rocky Graziano convinced the undersized Herman to return to Missouri. “There is nothing so false as a boxer, a puppet for a manager. They prostitute their brains and bodies for peanuts,” he said in a 1957 interview.

In the meantime, he was developing a reputation as a solid middleweight amateur wrestler and all-around tough guy. Stanley Canter attended high school with Herman and wrestled with him at the YMHA. According to a story related by Canter’s son Stan, Herman showed up at the Y one day an hour late and all ripped up. “Seems Bernard had flirted with some guy’s girlfriend, and then found himself surrounded by the guy and about 4 of his buddies. Apparently, Bernard took them all on and was the last one standing.” Herman was at the AAU nationals for three straight years, finishing fourth in 1950 after a loss to future pro Joe Scarpello and placing third in 1951 at 175 pounds. He was briefly at Purdue University in 1950-51, but there’s no documentation that places him on the wrestling team.

By then, he was developing other interests. In 1951, Herman turned to ballet, training on a scholarship at the Lalla Bauman School of Dance in St. Louis with Don Emmons, who’d make it big on Broadway, and Buddy Goldstein. They’d work out for five or six hours a night and then close out things at a bar across the street, said Goldstein, who thought Herman was consciously using ballet as a stepping stone to wrestling.

“He was not very big but he was strong and he was agile. And using the techniques he learned in dancing, to use in his act. If it was a real fight, with some of those guys as big as he was fighting, I’m not sure it would have worked,” Goldstein said. In fact, he was astonished when he later saw clips of Herman wrestling and performing as Starr. “His ballet techniques were really well done. I was surprised. He wasn’t that great in ballet when we were all together.”

Starr would later say he tried without success to break in around St. Louis and had one match in East St. Louis, Ill, for $5 a night. But father Joe couldn’t convince St. Louis promoter Sam Muchnick to give the pint-sized local a chance, so he head to Texas. After working on the undercards, he decided in 1954 to give ballet-style wrestling a whirl. In Amarillo, Texas, he put on purple ballet slippers and a matching leotard, and started executing the moves he learned with Goldstein.

Though the routine smacked of effeminacy at a time when Gorgeous George was a national phenom, but Starr took a more comedic angle, pirouetting around opponents and delivering ballet-style kicks to strategic body parts. “As a straight man, I was lousy,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1961. “I’d always wanted to get into show business. I took up ballet because an actor advised me, ‘You gotta be able to everything kid — sing, dance, act.'” Starr remembered the lesson; he continued to pay for ballet lessons even as he started to ride a crest of mainstream publicity and box office success.

Vincent J. McMahon inked him to a four-year contract on behalf of Capitol Wrestling, the forerunner of the WWE, and Starr broke a 22-year-old attendance mark in Washington, D.C., when he lost an outdoor match to Argentina Rocca in 1957. His mix of comedy, high spots and gamesmanship entertained the most hard-bitten critics. Even New York sports columnist Dan Parker, who loathed wrestling, loved Starr, calling him “an uncommonly gifted buffoon who is a combination of Nijinsky, [vaudevillian] Jimmy Savo and Jimmie Londos. … There’s nothing offensive about his routine.”

In short, he was fun to watch, said Ted Lewin, who wrestled on the New York scene at the same time. “If you don’t have the huge body or the face that looks like a truck hit it or that blonde hair, you’ve got to have something,” Lewin reflected. “He did have this ballet background plus it was well known that he could wrestle. It’s a gimmick. He came up with this idea, he tried it, they bought it, they went for it. It’s hard to believe they went for it, but they did.”

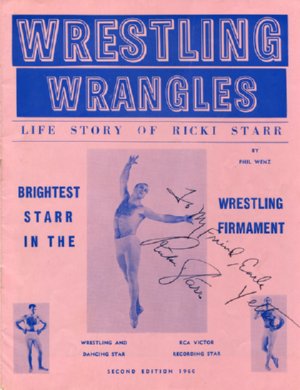

Starr’s top years in the United States were from 1957 to 1962. Pfefer booked him around the country, from arena to arena, as Starr tossed miniature ballet slippers to fans who screamed like he was John, Paul, George and Ringo wrapped up in one. Starr trusted Pfefer to handpick opponents who would go along with his routine, and paid him 20 percent of his payday for his services. “Jack I don’t know how much you ever took from your top boys but if it was 10%, 50%, or 80% I’m sure you were worth every penny of it,” Starr wrote “Kosher Pickle,” a.k.a. Pfefer, in November 1958. Still popping up on eBay every now and then is a 16-page promo booklet entitled, Wrestling Wrangles: Life Story of Ricki Starr. The Phil Wenz-authored promo piece contains pre-written features on Starr for entertainment, society, teen and sports newspaper and magazine editors. For instance, Starr was a wine connoisseur with a French Cote d’or Chablis as his prize. No kayfabe there, Street said years later. “He knew his wine. He taught me a lot about wine,” the Exotic One said.

Fellow wrestlers appreciated Starr’s ability to help them draw money and his conviviality outside the ring. “Ricki Starr was one hell of a wrestler. He could go. He was one hell of a competitor. He was one hell of a party man, too,” Lou Thesz told Scott Teal’s Whatever Happened to …? in 1999. Nick Kozak knew him in Texas and said Starr had a definite party animal quality. “Ricky loved life. Ricky, he was funny to be with, he made you feel good. He was up, he was up all the time,” Kozak said. “He was cool. We got along great.” Though Starr never held any major championships, he didn’t need to; his act was his drawing card and he kept on the move to prevent it from becoming stale in any one place. “If we run into places that aren’t ready for us, we’ll be killing the goose before it lays the golden egg. Right?” he wrote Pfefer in 1959.

In the early 1960s, McMahon started using Buddy Rogers as his feature attraction, as Starr branched out into the entertainment world he coveted. He released a record called “Shooting Star” through RCA Victor and guest starred on the two episodes of Mr. Ed as a wrestler and a bashful beautician. He was so well received that Arthur Lubin, a CBS director, announced the Mister Ed Company was planning a TV series for the 1963-64 season with Starr as the star.

And that’s where the Starr trail became convoluted. With the help of Tony Rocco, Starr hooked up with Paul London Promotions in England and moved his talents to Europe for most of the rest of his career. “He was immense when he came over there at first,” said Street. “He was a hell of a performer. I can’t say I was in love with the guy. He could be a cocky bastard; mind you, he had a right to be because he was good.” Starr used the airplane spin as his finisher to rave reviews. “This is no ponderous swing-round. It is fast and it is graceful,” British wrestling commentator Kent Walton said in The Grappling Game. “You could almost imagine Ricki is on some opera-house stage holding aloft a seven-stone-six-swan-necked ballerina instead of a fifteen-stone massively muscled Pole.”

Starr had a couple of brief appearances in the States thereafter. Gulf Coast historian and ex-wrestler Michael Norris said Starr altered his style when he toured in 1972 and 1973. “Still did the acrobatic stuff and wore the ballerina slippers, but the feminine stuff was gone. He did very well in Amarillo and had a good run in the Gulf Coast as well. The ballerina stuff was legit, he was a trained dancer, but he was also a shooter,” Norris said. Eventually, Starr changed into a Far Eastern gimmick, with a bald head, a top knot and a Fu Manchu mustache before he left wrestling in the late 1970s. Back in Europe, Starr headlined Gustl Kaiser’s international tournaments, wrestling in Munich and Vienna before wrestling for English indy promotions, including one run by superstar Jackie Pallo, in the late 1970s.

And there the story ends, largely because of Starr’s withdrawal from the wrestling fraternity. For years, Internet message boards have been full of “Where is he now?” queries about Starr, only to find, disappointingly, that he didn’t want to relive his life for other people. It’s possible that the last sweetness of Starr’s wrestling memories was drained years ago — it was half-a-century since he hit his peak in the United States. Perhaps there were other personal reasons for his disengagement; his letters to Pfefer refer to a girlfriend named Miriam, who drops out of the very personal correspondence without explanation. It was left to Ken Sowden, a member of the committee of the British Wrestling Reunion in the United Kingdom, to disclose Starr’s death, citing an email from Starr’s son.

In 2011, Greg Oliver talked with the late Billy Robinson about Starr. They were in England and Germany at the same time, counterparts in the ring because Starr was a showman while Robinson was all business. “Ricki and I were very, very close friends,” Robinson recalled. “Don’t know if he’s alive or not. Tell him to get in touch with me.”

A longer profile of Starr is in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes & Icons. Steven Johnson and Greg Oliver are authors of the series. Johnson can be reached at blakeslee_74@yahoo.com.