Over his 35 years in pro wrestling, Charles Sprott was known at various times as “The Gladiator” and “Super Gladiator” under a mask, as “Cowboy” Ricky Hunter, and as Buddy Sprott.

His long life came to an end today, February 8, 2022, at the age of 85.

Sprott was born March 1, 1936, in Winnipeg, Manitoba. His father, John, was a fighter pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force, who died in 1941, leaving his mother widowed at a young age with two children — Charles and his sister, Carol. Sports were his main interest, as he dropped out of high school in Grade 11. He played hockey, wrestled, lifted weights, and was an accomplished swimmer and lifeguard.

At the YMCA, he fell under the sway of some of the greatest wrestlers to ever come out of Winnipeg at that YMCA — and into the fire department. George Gordienko was there, and Gordon Nelson, both who’d go on to stardom around the world, and Albert “Ole” Olsen, who stayed home to wrestle and work in the Winnipeg Fire Department. While they all helped school Sprott, it was Olsen who found him a job, a stable base while he grew. For a time, Sprott and Olsen were actually both assigned to the same fire hall, so they could practice during their down time.

Sprott had always been a wrestling fan, having seen some on television, usually the shows out of Minneapolis and Chicago. “There were a lot of young wrestlers from the Winnipeg area who went into the pros, so we watched to see if we’d see anyone we knew,” Sprott told Scott Teal in Whatever Happened To … ? in the December 2002 issue.

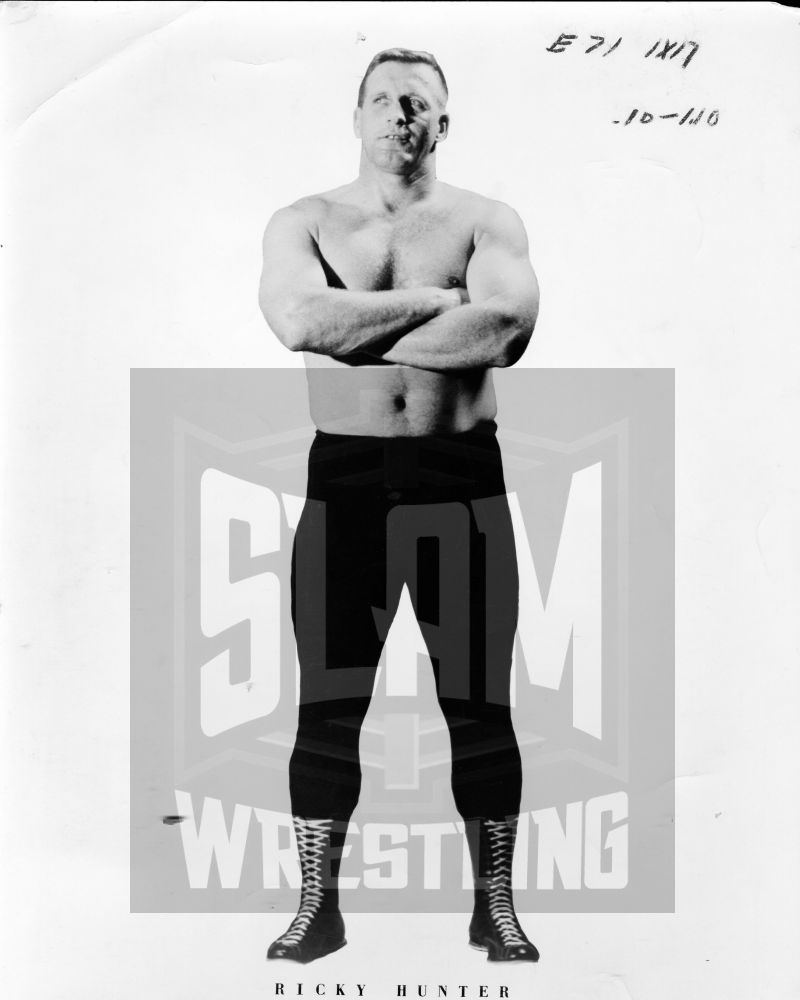

A Ricky Hunter promo photo. Photo courtesy Chris Swisher

Norland Wrestling Club was another place to train, and Sprott said it was about a year before he debuted as a professional, in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, against Olsen. Winnipeg was rich with wrestling at the time, with the Madison Boxing and Wrestling Club and the Atlas Wrestling Club putting on shows. For almost five years, Buddy Sprott wrestled on the local scene.

A connection in the fire department knew Verne Gagne, who was promoting out of Minnesota, and that was Sprott’s entry into the United States.

“Here I was, a young kid barely 20 years old, and I was traveling all over the country. It was magnificent,” he told Teal. “I would take time off from the fire department, or they would rearrange my work schedule to fit my wrestling schedule. The fire chief just adored me. He would come to see me wrestle in different places.”

Sprott improved with Gagne, who then arranged for him to head out to the Portland territory for Don Owen; Sprott quit the fire department to hit the road for good. It was Owen who suggested the name change to Ricky Hunter, thinking that “Sprott” sounded like a disease.

After a good, long stint in the San Francisco territory with promoter Roy Shire, Sprott headed cross-country.

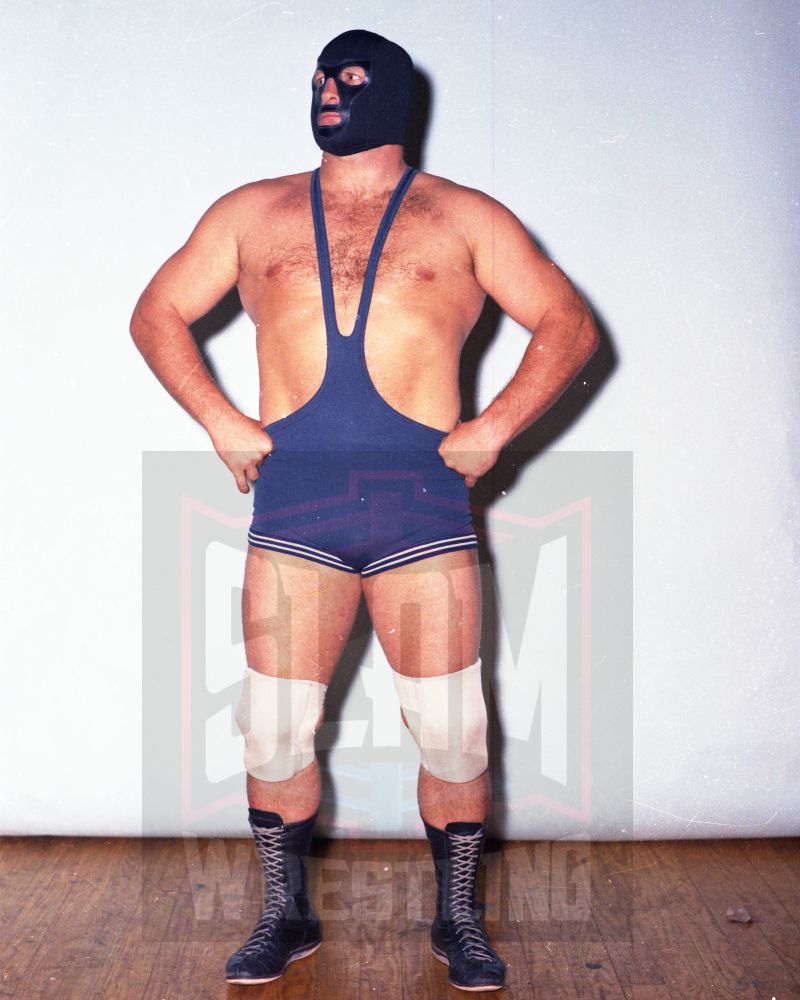

In the fall of 1968, he debuted in Eddie Graham’s Championship Wrestling From Florida under a navy blue mask and wearing a collegiate wrestling singlet. The Gladiator had arrived.

The Gladiator. Photo courtesy Chris Swisher

“Graham called Shire and asked if he could use me. Shire asked me if I wanted to go to Florida and I said, ‘Sure, I’ll try it’ and came down for what was originally a thirteen week contract. I wound up staying much longer than that as The Gladiator because it was working so well and really getting over,” Sprott told Florida historian Barry Rose in 2004. “The talent we had was tremendous at that time. Fellows like Jack Brisco, The Great Malenko, and Hans Mortier. I first met Hans over in Europe while I was wrestling in the tournaments in Germany. Mortier was an international wrestler and had been to many different countries. Nick Kozak and I had wrestled in the Pacific Northwest and Japan together and we were very close. He’s a fine gentleman and an excellent wrestler, as well as fellow Canadian.”

Jack Brisco mentioned Sprott in his book. “Ricky was always trying to impress the boys by using ‘big words.’ Joe [Scarpa] called him The Professor because he always wanted to show us how much he knew, or at least thought he knew.”

Sprott took his act abroad, working in Japan often, Australia, New Zealand, Africa, and in the United Kingdom. “Rick was a truly international wrestler and worked for various promoters around the World. In 1981 he toured the UK and faced many of the top stars we had to offer,” wrote British historian Ken Sowden after hearing of Sprott’s death.

“I met Ricky the first time going through Hawaii to Australia,” Dick Steinborn told Teal in the February 1999 issue of Whatever Happened To … ? “I took an immediate liking to him. He was very aggressive and in your face type of pistol type guy.”

On a national basis, many know Sprott from his time in the AWA, 1979-80 as an enhancement worker.

“When I was a kid, I remember hearing the name Buddy Sprott, because I was familiar with the Madison Cub and some of the other smaller clubs around Winnipeg playing around town,” recalled announcer/wrestler/historian Marty Goldstein. “And I remembered hearing he had gone on to wrestle in the States, but didn’t realize that he was Rick Hunter until the mid ’70s when he wrestled in Vancouver. He was a class every moment in the ring. A great athlete, strong. Pretty much anytime we saw him in the AWA in the late ’70s, early ’80s, he would bow to the crowd in the European traditional sportsman manner. Any time he was booked into a match, even on TV against the top guys, you knew that if Ricky had a moment to shine, he was going to look like a total pro.”

Sprott joined the expanding WWWF, transitioning to the WWF. For the McMahon company, he was enhancement talent as the Gladiator or Ricky Hunter, but also was assigned a job setting up the ring in the Southeastern part of the United States, where he’d referee as well. All told, Sprott worked for WWF for six years. “WWF was good to me,” Sprott told Teal. “It was getting close to the end of my career and they took good care of me. I worked fairly regular my first year, then I started slacking off. Instead of taking six bookings a week, I’d take three or four, then I tapered off from that.”

He held numerous titles, including the Florida heavyweight title twice as The Gladiator (1968-89), the Florida tag titles as The Gladiator with Lester Welch (1969), and the Georgia tag title as Super Gladiator, with Tommy Siegler, in 1973, and the Georgia TV title as well that year. North of the border, he was Canadian tag team champion in Vancouver with Guy Mitchell in 1975, and starting out, held the Atlas Junior Heavyweight title in 1958 and the All-Star tag belts with George Eakin in 1961.

He was also in a film, Moonrunners, from 1974.

In retirement, Sprott lived in Clearwater, Florida. He was married to Sherry Zirbel, a school teacher he’d met in Hawaii while wrestling, returning from a tour of Japan. They were married 34 years

Asked by Teal if he ever regretted choosing wrestling over stable employment, Sprott said, “I wouldn’t change a thing. I would do it all over again. I realized that the wrestling was becoming addictive. It was something I was never going to be able to give up because every day was Christmas if you can imagine. Every corner you turned. Every state I went into, I met people. I saw the world and got paid to do it. I didn’t make millions of dollars, but I certainly lived like a king.”

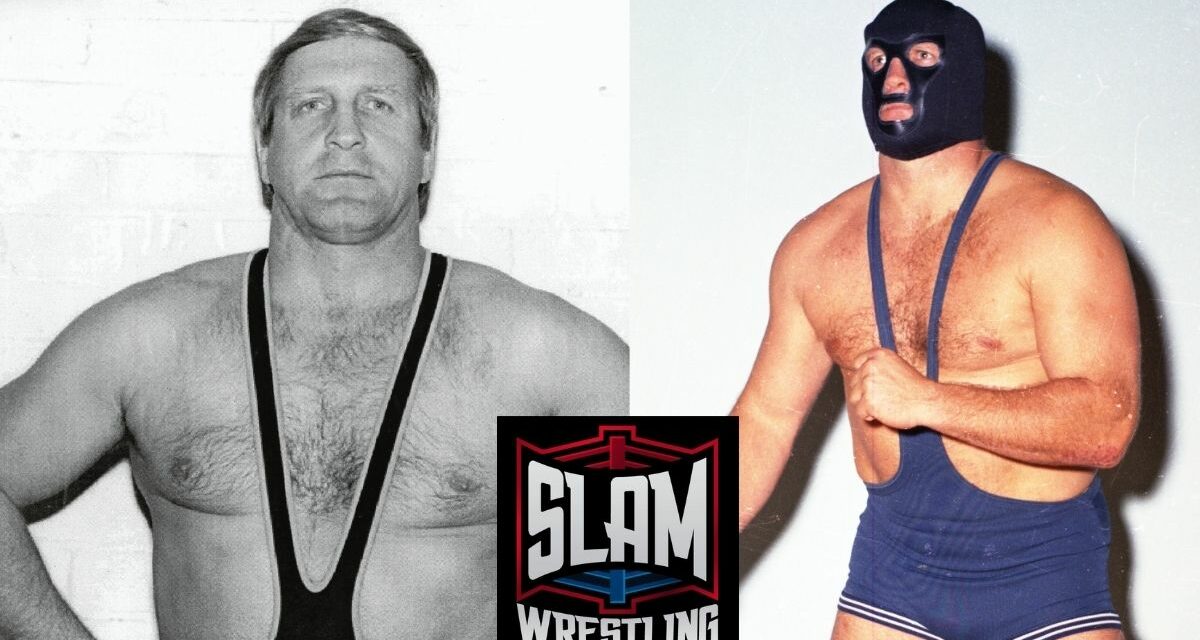

TOP PHOTO: Ricky Hunter and The Gladiator, both photos courtesy Chris Swisher