Had circumstances been different, more people would have known about the wrestling career — amateur and professional — of “The Great Wojo” Greg Wojciechowski. As it turned out, it was the troubled youth of Toledo, Ohio, that were the beneficiaries of his other skill: teaching.

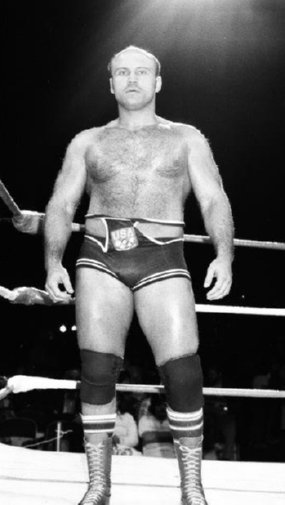

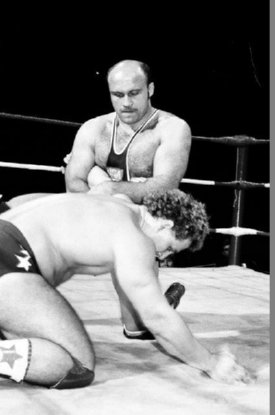

“The Great Wojo” Greg Wojciechowski. Photo by Scott Romer, scottromerphoto.com

Wojciechowski was on the 1980 United States Olympic team, but didn’t get to compete because of the boycott, his nation deciding to protest the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan by staying home from the Games in Moscow. And, as a pro, any opportunity that he could have taken on a national basis was impossible because of matters on the home front.

He’s in the news these days as a honouree in the 2015 George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame at the National Wrestling Hall of Fame Dan Gable Museum in Waterloo, Iowa.

Reached at his home in Toledo, Ohio, it becomes obvious pretty quickly that Wojciechowski is not one to brag.

“Usually I don’t get too excited about Hall of Fames, but this one is connected with the Dan Gable Museum, so I was enthused about it,” he said about his upcoming induction on the July 10-11 weekend.

THE GREAT OLYMPIAN

Mike Chapman is the museum’s founder, and while he isn’t involved in the organization any longer, he remains one of the most respected journalists and historians covering amateur wrestling. He is pleased that Wojciechowski’s accomplishments are being recognized.

“There’s no question he’s one of the finest heavyweights in American history, and I’m glad to see him get this honour, because I think he’s been somewhat overlooked. He certainly deserves every bit of accolade that comes his way,” said Chapman, more than happy to list off some of those feats: “He was a three-time NCAA finalist, a tremendous competitor, and his post-graduate record is superb. I’ve got him down as winning a total of 13 national titles post-graduate. That’s a commitment. Then with his one NCAA title, that’s a total of 14 national titles. Those 14 national titles puts him in America’s elite. He’s up there with Bruce Baumgartner, who has 18, Wayne Baughman, who has 16, Mike McCready, who has 15. Anyone who has won over 10 national titles is in an elite category in my estimation, and Greg fits that category, no question.”

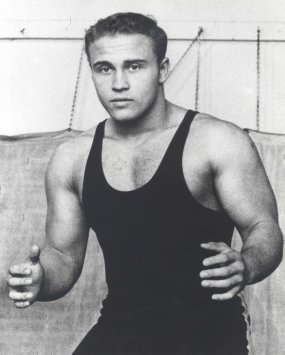

Greg Wojciechowski, amateur legend. Courtesy the University of Toledo

Worth noting, said Chapman, is that five of those national titles are in the Greco-Roman style and eight are in freestyle, proving that Wojciechowski was skilled in both disciplines, if not his timing.

Wojciechowski’s successes began at Whitmer High School in Toledo, Ohio, where he was state champion in 1967 and 1968 as a heavyweight. At the University of Toledo, his elite status was confirmed, as he won the NCAA heavyweight championship in 1971 as a junior, and was the runner-up in both 1970 (to Jeff Lewis) and 1972 (to Chris Taylor).

Involvement in amateur wrestling often means a nose turned down on professional wrestling, the showbiz-like wacky brother of the amateur game. Wojciechowski said that it had always been on his mind though, and his 6-foot, 260-pound body, with bulging arms and thick chest, made for a straight-forward enough transition: “I thought about it all through high school. I wanted to make the Olympic team first, then I wanted to try to get into professional wrestling and make some money.”

But when you’re good, you’re good, and Wojciechowski was in the Olympic picture in 1968, 1972, 1976, 1980 — but never competed in an Olympic Games. A lesser man might have been defeated by the string of disappointments, political shenanigans and sheer bad luck that prevented an Olympic participation.

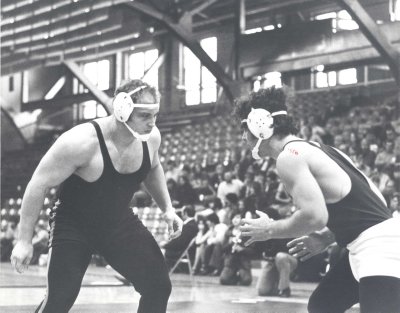

Greg Wojciechowski, left, in amateur action. Courtesy the University of Toledo

Consider that he was a runner-up in freestyle for a spot on the Olympic team three different times: 1968 (losing to eventual bronze medalist and future pro star Bob Roop), 1972, and 1976.

The 1972 one stands out. For one, he was older, more mature, and one of the top collegians in the country. He lost in the Olympic trials to the gargantuan Chris Taylor, from Iowa State, who’d just beaten him in the NCAAs. Their biggest bout before 1972 was in the 1970 Midlands, with Taylor again prevailing.

In August 1972, Taylor talked about Wojciechowski, against whom he measured his improvements through the years. “He always used to beat me — but I’ve won the last five or six times.”

Taylor was a sight to see. He was a massive figure, 460 pounds, a virtual building on legs. The U.S. Olympic Committee believed in his potential so much that they allowed Taylor to compete in both freestyle and Greco-Roman, the first American to do so.

Wojciechowski had hoped to be tapped for the other spot (NCAA wrestling is freestyle, and Greco-Roman isn’t practiced at the schools).

At the Games in Munich, Taylor won the bronze in freestyle, losing to the legendary Russian Alexander Medved. But he flamed out in Greco, with the famous over-the-head suplex by West Germany’s Wilfried Dietrich the lowlight.

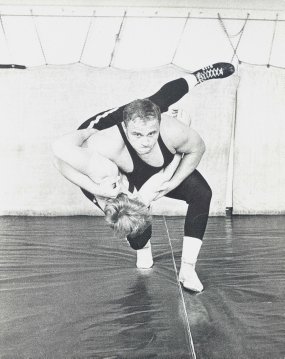

Greg Wojciechowski demonstrates a takeover in practice. Courtesy the University of Toledo

“His heart wasn’t in Greco,” said Chapman. “He went out and got pinned right away. A lot of people don’t know that.”

To compete in the 1976 Olympics, Wojciechowski dropped weight to the 220-pound level. Russ Hellickson bested him in freestyle, and future pro Brad Rheingans took him out in Greco.

“Brad knew his stuff. I cut down to 220 for about four years,” recalled Wojciechowski. “He came out of nowhere in Greco-Roman and beat me. Probably one of the better matches I wrestled, he beat me like 7-4, or 7-3. He was a good amateur.”

Come 1980, Wojciechowski was back at it chasing the elusive dream. He had to get through two big names — 1976 Olympian Jimmy Jackson of Oklahoma State and Bruce Baumgartner, who would go on to future Olympic success (two golds, a silver and a bronze) — to get there, but he did.

But the U.S.S.R. invaded Afghanistan in December 1979, and the Games in Moscow in July became a political hot potato. The United States, led by President Jimmy Carter, were at the forefront of the boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics; other major countries that also stayed home included Japan, West Germany, China, the Philippines, Argentina and Canada.

The Washington Post ran an Olympic preview despite the boycott: “The Soviets should win eight golds, one silver in the freestyle. Without the Japanese and West Germans in the Greco-Roman events, the Soviets could be just as awesome in that competition. Greg Wojciechowski of Toledo and Russ Hellickson of Oregon, Wis., would have made matches very tough for the USSR. Ben Peterson would have been a safe bet for a silver and, with a little luck, could have won a gold.”

THE GREAT PRO WRESTLER

Wojciechowski, disappointed, turned professional in September 1980. He learned the sport from Jerry Jaffe, an old friend from high school who’d turned pro, wrestling as Jerry Graham Jr. Three years senior to Wojciechowski, they’d also worked out as amateur wrestlers at the Toledo YMCA under a program run by pro wrestler Dick Torio.

“I trained him at Torio’s Gym. He was a good student. A lot of amateurs can’t make the transition,” recalled Jaffe. “He understood we were trying to make money.” Interested in furthering his training, Wojciechowski and Jaffe also traveled to Al Costello’s gym to learn a little more from the Fabulous Kangaroo.

To help the money-making prospects, it was then that Wojciechowski grew the Fu Manchu-style mustache that he became known for.

Wojciechowski said he wasn’t ever “smartened up” to the inner-workings of pro wrestling — “I always knew it,” he said. His amateur buddies recognized his years of dedication to their sport, and accepted that he needed to make a buck. “I didn’t get too much (hassle). It was 1980 and I was already 29 years old, so it was time.”

It was in Dick the Bruiser’s territory that he first debuted, working Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and other mid-west states.

Both Bruiser and Crybaby George Cannon, based out of Windsor, Ontario, wanted Wojo, “so he got instant booking,” said Jaffe.

“The Great Wojo was a mean-looking guy, pushing 280, 290, and he was benching 500 pounds,” said Jaffe. “He got the job done. You had to believe him. When he came to the ring — that was still in the days of kayfabe, and people did or didn’t believe — but when Wojo came out of the dressing room, the one thing you had to do, you had to believe that he was tough. There was no other way about it. If somebody tried to get cute with him in the ring, he wouldn’t last very long.”

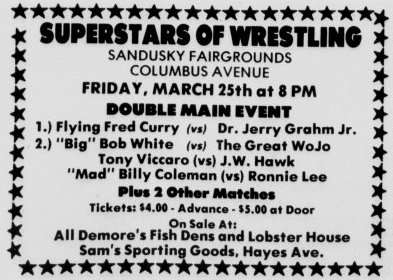

Sandusky, Ohio, March 22, 1983

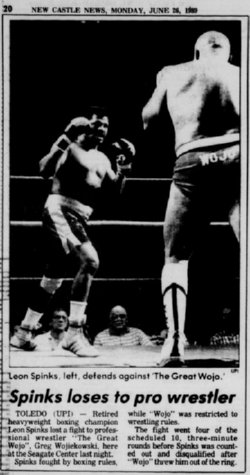

Dick the Bruiser was the central star of his WWA promotion, but Wojciechowski got his moments too, including three runs with the promotion’s heavyweight title. One of his foes in the summer of 1986 was a newcomer named Scott Rechsteiner (later shortened to Scott Steiner). A tour of Japan was a career highlight, and he wrestled in Puerto Rico and parts of Canada. And don’t forget the 1989 boxer versus wrestler bout against Leon Spinks in Toledo.

Perhaps the best gimmick for The Great Wojo — “When I turned into a heel, I thought that would be good for arrogance.” — was his $10,000 challenge.

A newspaper clipping from Wojo’s fight with Leon Spinks.

“That was Jerry and my idea. Especially when I got the belt, then we challenged Hulk Hogan, belt for belt,” Wojo recalled. “It never happened.”

Jaffe described the gimmick: “They had five minutes to pin Wojo for $10,000 … Usually Wojo beat these guys in 15, 20, 30 seconds. There were a couple of guys that came up through the amateurs that were pretty good, but in amateur wrestling, they don’t let you stall, they keep you moving. But who makes the rules for these challenge matches? I’d say 90% of these challenge matches Wojo won in less than 30 or 40 seconds. He’d never try to hurt the guy, but he’d get him down and pin him.”

In today’s litigious society, it’s not a gimmick that could work now — and it didn’t everywhere back then either, said Jaffe. “I would check the laws of the state. In Ohio, it’s called an assumption of risk law.” It was okay in Indiana, but not Michigan, for example. Challengers would sign a release and the promoter made sure they were fit enough to compete, sometimes even requiring a doctor’s note. “It was a draw. People liked it, people enjoyed it.”

THE GREAT DAD AND TEACHER

For all his successes in the squared circle, it’s Wojciechowski’s life outside of it that truly defines the man that he is.

In 1986, with three sons aged 13, 10 and 7, Wojciechowski and his wife divorced and he took custody of Chad, Kyle and Ryan. All decisions moving forward were made far more complicated.

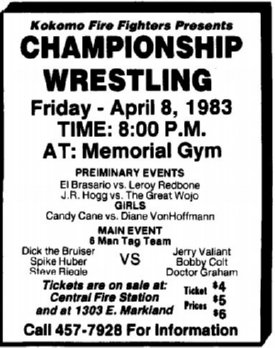

Kokomo, Indiana, April 4, 1983

“I had to slow down quite a bit,” admitted Wojciechowski.

Pro wrestling became a sideline, a part-time job on weekends. His main job was as a teacher and a coach, with one year at Archbold in Toledo, and then 27 years at Libbey High School.

It was not a cakewalk.

“I taught a vocational program. I got kids that were a dropout problem, disenfranchised. I taught them just reading, writing and arithmetic, and I tried to place them on jobs,” he said. “These were tough kids, an inner-city school. It was good to have a shaved head and a reputation that was bigger than life.”

While it may not have been easy, it sure was rewarding “I loved it. It was a good job. It was a gift. Most of the time I could be nice and still get my way, because I could intimidate them a little bit if I had to. But I really enjoyed the job.”

There was overlap from teaching to pro wrestling, until he was forced to stop wrestling in 1999. “I got more respect. Having a shaved head, being big, being that, until we got TV eventually in Toledo, then it was wall to wall. That helped my career in teaching.”

In 1999, Wojciechowski’s life was changed dramatically. He was working out with some high school amateur prospects at Torio’s gym when he felt a burning sensation in his chest. Uncharacteristically lightheaded and weak, paramedics were called for him. It turns out he had a dissected aorta and had been very close to dying.

Jaffe wasn’t there in the gym, but was in the hospital. “He wasn’t taking any visitors but I just barged into the hospital anyway, because he was my best friend. They let me stay.”

Sixteen years later, Wojciechowski dwells on the positives after his heart was repaired.

“The doctors told me, after three or four days in intensive care, ‘The good news is, if you keep taking your medicine, eat right, you might live for a while; the bad news is no more heavy lifting, no more wrestling. I can live with that,” he said, immediately giving up pro wrestling at the age of 49.

It could have been worse, he explained. “I was about to wrestle a small match in Michigan the Saturday after that, so I was lucky that it happened when it did, not out in the countryside of Michigan. I wouldn’t have survived. It was just 15 minutes to the hospital right here in Toledo.”

Forced onto long-term disability and ordered to watch his blood pressure, his buddy handled it all as well as could be expected, said Jaffe.

“When he came out of the hospital, he seemed to deal with it, I guess that’s the best word. You can’t be happy about it. Most people die from it,” said Jaffe. “He almost died, came very close to dying. He got on disability. He goes for long walks. He works out in the gym within the guidelines of his cardiologist. Now he’s up in his 60s. He looks good. He’s lost some weight, weighs about 240 now; doesn’t look skinny by any means, but he doesn’t look as big as he used to.

The Great Wojo arm bars an opponent. Photo by Scott Romer, scottromerphoto.com

“He’s accepted things and gone on to be a good father, grandfather, good husband, good family man. He’s big on family.”

Wojciechowski’s legacy in amateur wrestling is undeniable. It’s certainly acceptable to wonder what he could have done as a pro — if he’d turned pro in 1972 as originally planned, just after his expected Olympic debut — if he hadn’t gotten divorced and taken responsibility for his three boys — if he had been able to travel — if he’d been given a shot in a bigger promotion.

“I think I came in a little late. It was maybe five, 10 years before me, the guys were doing good. Then the big cables took over, Turner out of Atlanta started with the big cable, then the WWE out of New York. They really put the squeeze on us and the local promotions,” considered Wojciechowski.

There was talk of taking a year off from his teaching job, allowed by his union contract, to work for amateur enthusiast Verne Gagne in the AWA, but it never came about.

There was a WWF experience. “I worked for them a few times in Detroit. First of all, I wasn’t willing to travel, so that kind of limited me right there. But they didn’t show a lot of interest. You had to be able to travel to be a good professional wrestler.”

Jaffe always thought that Wojo could have served WWE well. He could have gone to high schools during the day to work out the wrestling teams, but then in the ring that night, he would put up a battle, but ultimately do the honours for the other wrestler, building the stardom of the other guy, as in, “That Hulk Hogan must really be tough.”

“I always thought Wojo would have been perfect for that operation because they had all these colourful guys and they could have had a straight man,” said Jaffe.

While Wojciechowski did stop pro wrestling, he continues to teach amateur wrestling, even if he isn’t as active as he once was. “It’s always fun to stay in touch. I like working with kids,” he concluded.

Through everything, Jaffe has always been impressed by Wojo’s humble nature.

“He’s a very shy, modest man. I’ve seen him mad, and it’s not very often, it’s very rare. He’s a very calm, sedate person,” said Jaffe. “But you’ve got to have that competitive instinct, that fire in your belly some place to do the things he did as an amateur.”

Jaffe is planning to make the trip to Waterloo, Iowa, to see his friend inducted into the Tragos/Thesz Hall of Fame. “He got screwed on the Olympics so many times, at least he’s getting this.”

TRAGOS/THESZ CLASS OF 2015 STORIES

- July 13, 2015: Guest Column: Torch’s Wade Keller worthy of Melby Award

- July 12, 2015: Tragos/Thesz HOF induction: From Bee to Glamazon to Wojo

- July 11, 2015: NWHOF honors Kurt Angle with presentation during weekend festivities

- July 11, 2015: Hopefuls try to get on WWE radar at tryout

- July 8, 2015: Jim Ross: Kurt Angle ‘was born to be a wrestler’

- June 22, 2015: Melding two worlds: Olympic gold medalist Kurt Angle to attend NWHOF weekend

- June 17, 2015: Career interrupted: The story of “The Great Wojo” Wojciechowski

RELATED LINKS