The year 1924 had been disastrous for both Marie Didderich and Virginia Mercereau – the ring name of the woman who rose from obscurity to stake her claim to the women’s middleweight wrestling championship of the world. If she had experienced career highs, they were outweighed by the calamitous ruin of her relationship with a man she thought was a boxing star – and her husband – but was really just a two-bit conman from down the block, all of which we detailed in Part 1: Virginia Mercerau: Early women’s champ bamboozled away from ring.

But the pain of 1924 and 1925 only served to drive the ambitions of a young woman left for junk on the scrap heap of the wrestling business. Marie Didderich was down, but she refused to be counted down. This is the second part of the story of a young girl from Wisconsin who dared to dream big and found success in every endeavor she dared. This is the final chapter in the story of Virginia Mercereau, champion, hero, star, and survivor.

Part 2: Virginia Strikes Back

The years 1925 and 1926 represent the dark ages for fans of Virginia Mercereau. There are no records of the activities of Marie Diderrich for the majority of 1925 or the entirety of 1926, indicating that she had likely taken time off from wrestling to return to normal life in Milwaukee – full of 9-5 jobs, errands, and lazy Sundays, but mostly bare of conman and other n’er-do-wells.

Only in February of 1927 did the once-dominant champion reappear with a big statement of intent – she was moving to Chicago. Marie Diderrich may have dropped the first fall but would not be beaten.

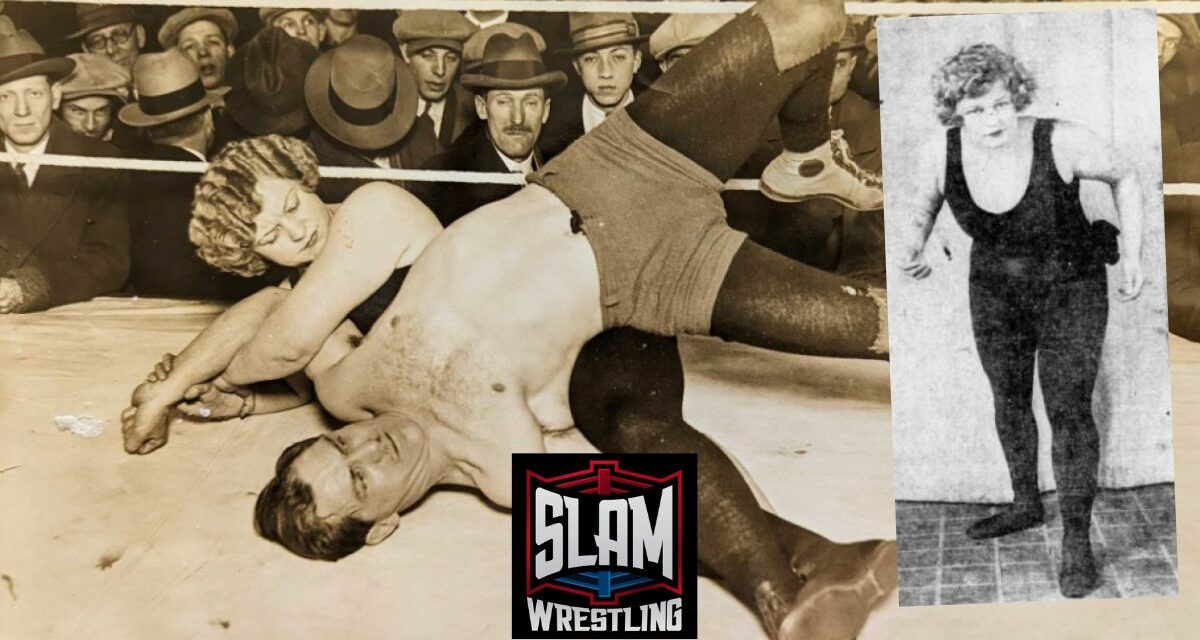

Virginia Mercereau and Ad Herman wrestling. NEA press photo, Feb. 12, 1927

Back In the Big Time

Mercereau had briefly dipped her toes in the water of the big city wrestling with Doc Krone. But her return in 1927 is a defiant answer to anyone who may have remembered her embarrassing marriage and manager fiasco of 1924.

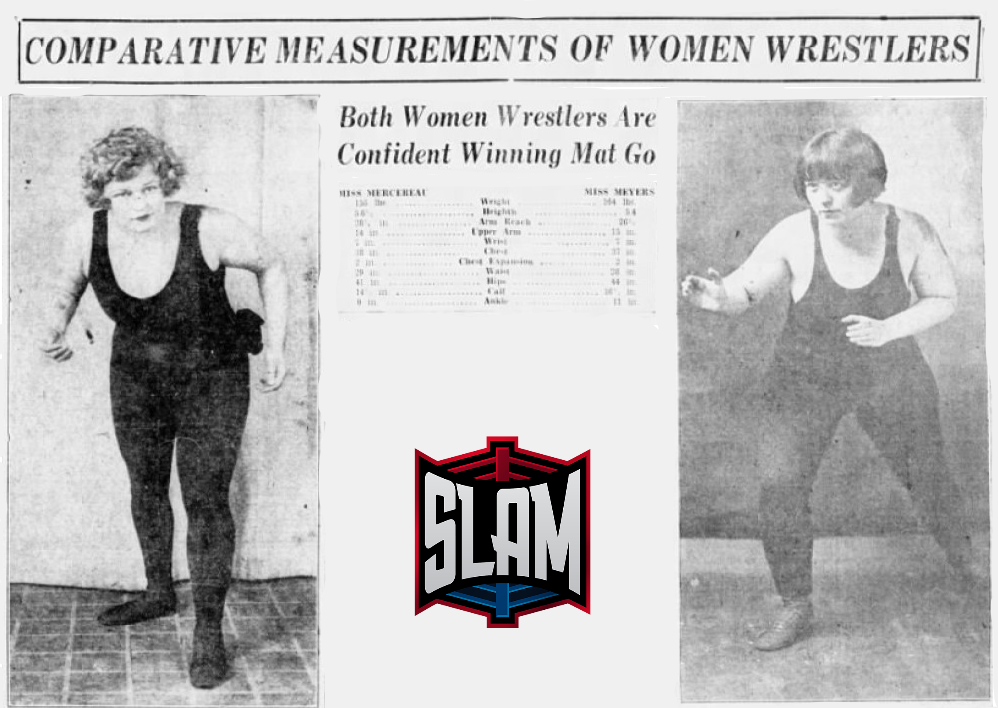

Diderrich reappears in the records in February of 1927, basing herself at Kid Howard’s Gym in Downtown Chicago, training with Ed (sometimes “Ad”) Herman, a middleweight contender. The venue was a popular training ground for pugilists and wrestlers alike and was a great place to build a reputation – something she immediately did.

On March 11, 1927, Virginia Mercereau added another title to her already impressive list of accolades – hero. A fire ripped through the five-story building downtown that hosted the gym, sending wrestlers, boxers, trainers, and other civilians screaming into the street – some half-naked. Some 300 guests at the next-door theatre rushed into the street to survey the scene when Kid Howard and Virginia Mercereau ran into the building, saving a young girl (possibly her sister) who had been overcome by smoke.

The story made the national press, and suddenly, Virginia Mercereau was back in the zeitgeist.

The Wager Returns

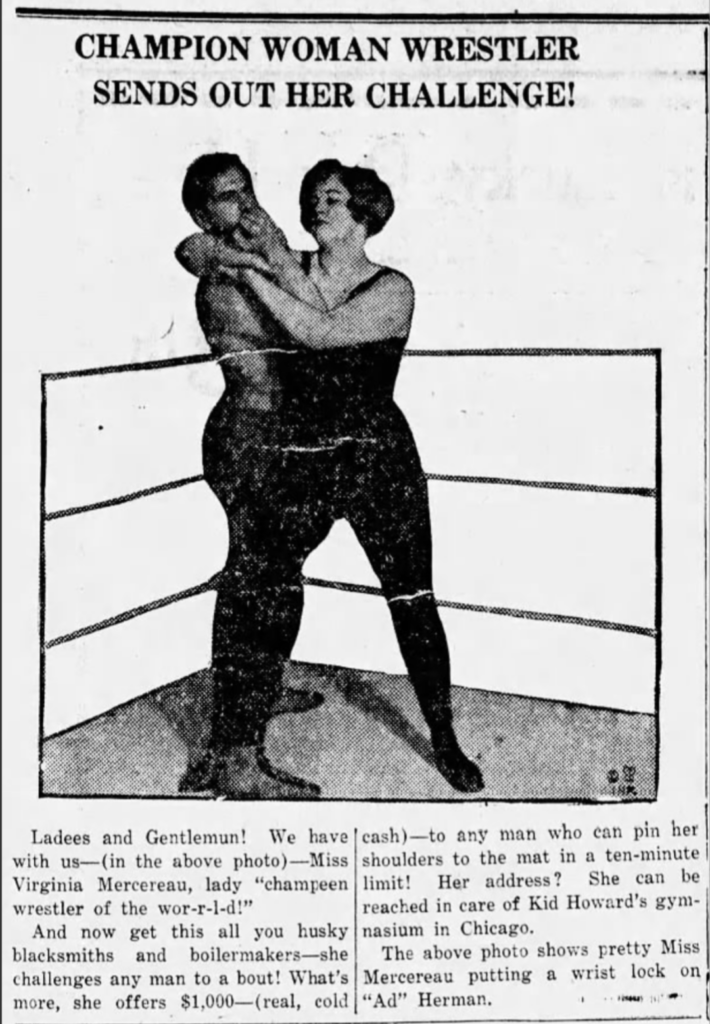

With a return to the ring, Mercereau once again staked her belief that no man of her size could throw her within a set time limit. Her stake was no longer a measly $150 bounty, replaced with a hefty purse of $1,000 (nearly $18,000 in today’s currency – now that’s foldin’ money). But the improved stakes required a bigger task – contestants were required to pin Mercereau for six seconds within a 15-minute time limit.

Mercereau’s first match on her comeback trail was against Soldier Mack on April 26, 1927, at the Appleton Guard Armory in Appleton, Wisconsin. Soldier Mack was Harry McKinley, a former soldier turned grappler who appears sparingly across Midwest wrestling cards in the 1920s and ’30s – the pair serving as the undercard to Karl Pozella and Hassan Hamey.

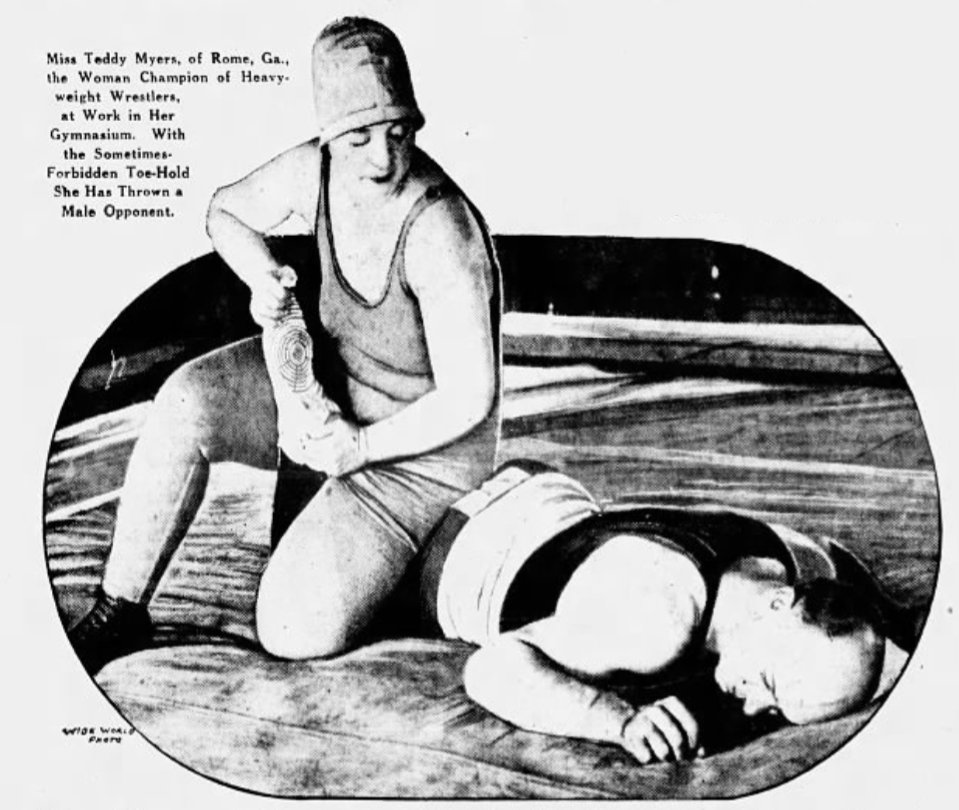

But almost as soon as Mercereau reemerged, so did the challenges from rivals. The first to issue a challenge was Teddy Meyers, originally of Youngstown, Ohio. Meyers (real name Zelle Wiseman) was an up-and-coming grappler who knew Mercereau was scheduled to arrive in Evansville, Indiana, to face a yet-to-be-found male competitor but who instead threw her name in the hat instead.

Mercereau accepted, and the match occurred on June 13, 1927, at the Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Coliseum in Evansville, Indiana. The bout – which shared the undercard of a Hans Bauer-Nick Valkoff main event with another former Mercereau victim, Soldier Mack, and George Walker – saw Mercereau decisively defeat Meyers in just 24 minutes.

Itinerant

Wrestling in the late ’20s had already begun the slow processes of coalition towards crude proto-territories, with the Boston stronghold of Paul Bowser and that of his Southern Californian associate, Lou Daro, perhaps the best examples.

Still, barnstorming was the norm for more than a fair few grapplers, and Mercereau was no different. So unique was her appeal that local promoters often balked when presented with an opportunity to book the women’s champion lest the situation develop into a farce, a riot, or a picketed affair by the local busybodies.

Because of this, Mercereau was forced to adopt a far more elaborate setup to promote the few bouts she could book. After leaving Indiana, for instance, Mercereau’s camp moved from Kid Howard’s Gym in Chicago to the Hermitage in Ogden, Utah, ahead of her next match-up in that city. Because the peculiarness of a women’s champion – especially one out in the rugged Wasatch Front – was still so new, much of the salesmanship for the bouts came from the sparring sessions between Mercereau and Ad Herman, her training partner.

As was the case in Chicago, Mercereau would train and spar at her camp with locals getting a chance to see a real-life superhero in the flesh.

Her opponent in the Beehive State was Jack Reed, a Danish-born wrestler who appeared on a smattering of cards in the late 1920s and early ’30s.

Reed was no slouch, however – especially when you consider the company he kept. On November 5th, for instance, a wrestling exhibition was given by Jim Londos, Greek wrestling champion and Jack Reed in Ogden, to a crowd that included former governor and secretary of war George Henry Dern.

A Reliable Act

Fortunately, Mercereau at least found another partner, as the previous bout with Meyers was clearly part of a routine run for local associations. This time, the North Lake Park Association in Mansfield, Ohio, was lucky enough to get the hotly-anticipated contest between the women’s champion of the world (and defeater of Cora Livingston) and a young upstart looking to knock her off her perch.

Both women arrived in Mansfield on Thursday the 20th, Mercereau from Chicago and Meyers from Georgia. Local bureaucratic excitement was raised to such a fervor that both women were offered “the freedom of the city and other courtesies.”

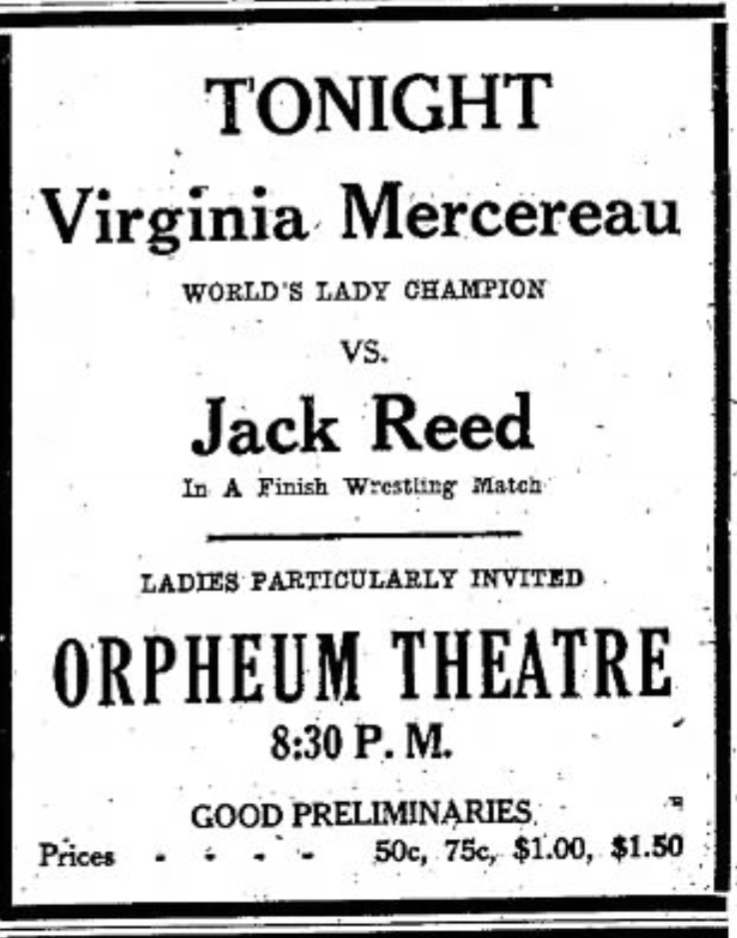

The local coverage for the bout was impressive, including a fantastic “tale of the tape” that I’ve included below:

Because it’s a bit blurry, here is the actual “tale of the tape” stats (or as best as I can make out, anyway):

| Miss Mercereau | Miss Meyers | |

| 156 lbs.

5’ 6” 26 ⅛” 14 6 18 2 29” 41” 15” 9 ½ |

Weight Height Arm Reach Upper Arm Wrist Chest Chest Expansion Waist Hips Calf Ankle |

144 lbs. 5’ 4” 26 ½” 13 7 31” 2 30” 44” 16 ⅓” 11” |

Interestingly, Mercereau, in declaring her confidence ahead of the match, stated that the two had first met a year ago, with a result similar to the Evansville clash – two falls in quick succession. This is likely just an attempt to provide greater provenance to the feud – and Meyers’ pursuit of Mercereau.

Meyers, for her part, was equally confident:

I am in better shape for my return match with Miss Mercereau, and I believe I will be the victor tomorrow. I have improved my technique and have gained considerably more experience since I last met Miss Mercereau.

– Miss Teddy Meyers, Mansfield News Journal, Mansfield, Ohio, October 20, 1927

The return match was hailed as a massive success by organizers of the North Lake Park Association. “Miss Virginia Mercereau, Chicagoan and world’s champion woman wrestler, successfully defended her title in a true slam-bang match at the Coliseum Friday night before some 1,000 customers,” read the copy from local sport’s ace “Keg.” Mercereau won the first and third falls against Meyers, taking the first in 23 minutes after applying her famed headlock (which she claimed to have picked up from Ed Lewis himself) and body scissors for the third fall.

For her part, Meyers won the second fall with a toe-hold, but it was the power of Mercereau that was just too much for Meyers to contend. The headlock, which scored the first fall, was a determining factor – weakening Meyers in the latter stages: “I thought she had broken my jaw,” she told the News Journal the next day. The news was also reported back home in Appleton – always proud of its former residents.

The routine was so effective that the women met in Atlanta in December. Local promoter John Contos had been promising local mat fans “something different” on the December 11th card at the City Auditorium, with Meyers – the local hero – and Mercereau the surprise.

Contos was so confident in the booking that he showed news clippings to back up his claim that “wherever Miss Mercereau had appeared, she had made a distinct hit with the fans, both by her skill and ability of disposing her opponents.” He also confirmed that he had held off booking the contest until getting advice from other promoters who had hosted Mercereau – finding a spotless resume.

The latest Meyers-Mercereau contest was on the undercard of a stacked card, including local favorite (and future promoter) Paul Jones (not that one), “Scotty” McDougal, Jim Browning, and Charlie Hanson. Again, Meyers was at an eight pounds disadvantage, but she thought her skills (and possibly an advance agreement) would finally see her through – it didn’t.

Teddy Meyers claims the women’s world heavyweight wrestling championship.

The Stage Beckons

Mercereau’s next appearance was back in Chicago as part of the Chicago Tribune’s Good Fellows show to entertain First World War veterans at the local Speedway Hospital. Mercereau was joined by Kid Howard, several amateur boxers, and an entertaining troupe to bring joy and distribute presents to the bedridden veterans. There were boxing bouts, music from the Chicago White Wings band, and plenty of vaudeville excitement from the pair of Si Jinks and Lillian Hartford.

The addition of vaudeville to the entertainment was fitting, and not just because vaudeville formed such an integral part of early 20th-century entertainment, but because it was another detour in the career of Marie Didderich/Virginia Mercereau.

This charity event is the first instance of Mercereau appearing in a vaudeville performance, but it wasn’t her last. Getting bookings was still an issue despite her renown. Sure, there were the bouts with Teddy Meyers, but as with Cora Livingston some four years prior, there was only so much juice to squeeze. The Meyers-Mercereau rivalry could still enjoy coverage, as the January 29, 1928, edition of the San Francisco Examiner attests, but only one woman could win – and that was the issue.

Meyers had followed a similar path to Mercereau, using her loss to launch her title claims – the heavyweight title in this case. As before, assigning yourself a weighted championship to avoid stepping on the toes of other female grapplers was effective – but the real draw was intergender matchups.

There were still matchups with men, such as a victory over Carley Peterson in Milwaukee in early December 1927 or against Howard Blazer on February 1, 1928. However, these events were sparse and often included no other wrestling. The Blazer match, for example, was the only match-up and was followed by a dance.

The issue was bookings – or, namely, the need for bookings she could obtain. Doc Krone tried, often in vain, to promote his star with engaging photos and copy designed to showcase the impressive skills (and record) of Mercereau.

But nothing seemed to work.

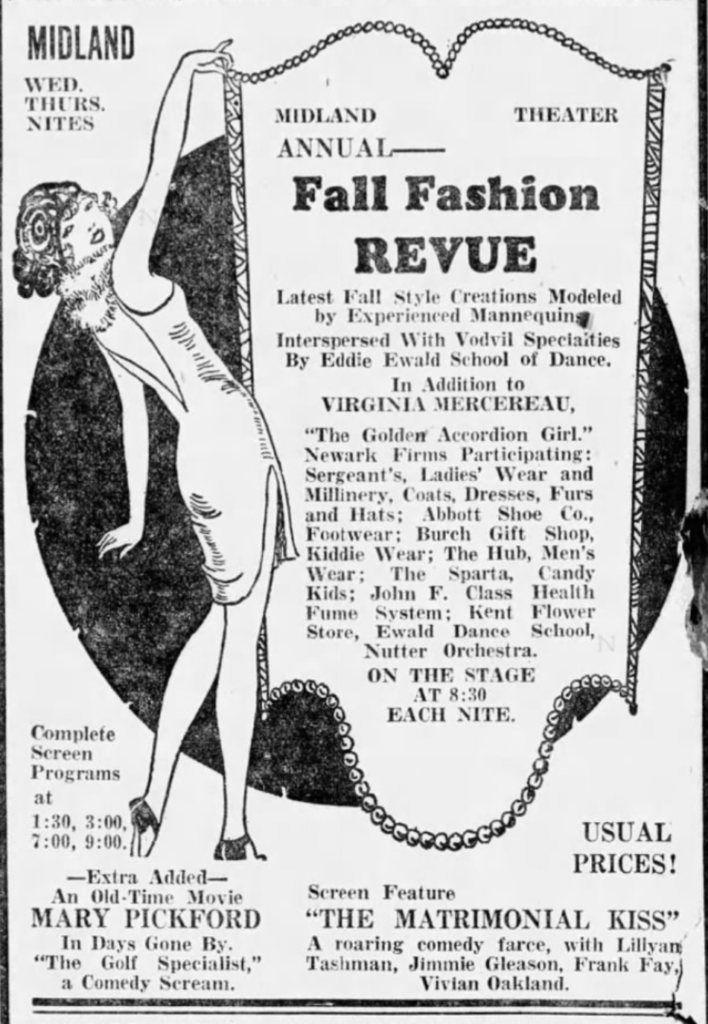

Golden Accordion Girl

So, what did Virginia Mercereau do? She picked up her accordion and kept right on going.

Finding bookings drying up, Mercereau turned to vaudeville to stay relevant. A musician in her youth, she found limited success as the “Golden Accordion Girl, Virginia Mercereau.” The act was a way to get bookings, keep her name in the public eye, and use the vaudeville stage to coax potential male opponents into the ring.

And it wasn’t a success. Sure, there were a handful of bookings here and there over the next year or so, but more was needed to make a go of it. And without demand, there was minimal income, requiring Marie Didderich to do a serious rethink.

More Than Just a Pretty Face

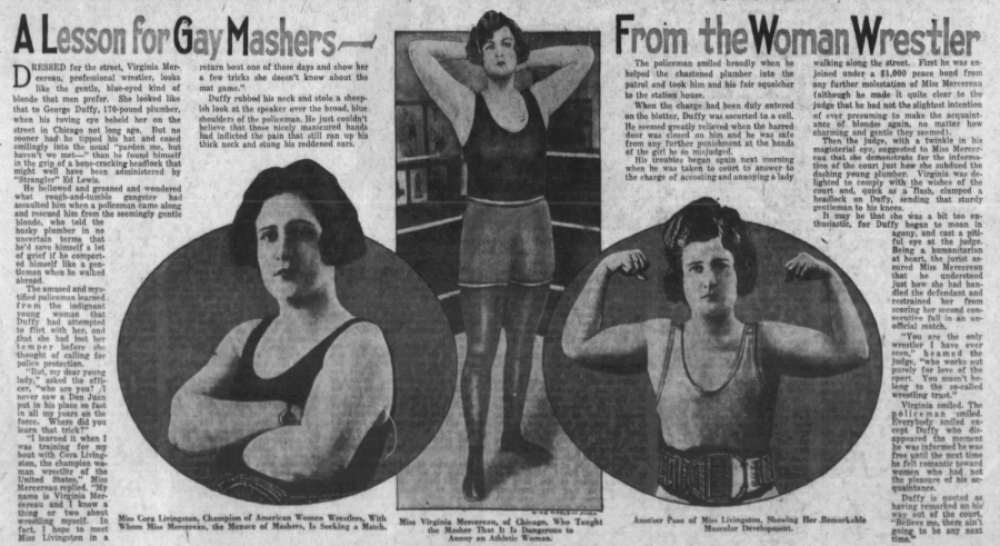

Despite the reduced bookings, Marie Didderich had no problems keeping the Virginia Mercereau name in the press. Part of it was down to her unique story and impressive skills, but some were down to her looks – and the attention they drew from “smooth operators.”

Despite her “unblemished” record, Mecrerau was still a young woman in Chicago – with all the catcalls that entailed. But Mercereau wasn’t one to take catcalls lightly – just ask George Duffy, a local guy who had his eye on the champ. On July 31, 1929, Duffy caught a glimpse of Miss Mercereau as she was window shopping.

George Duffy got a crash course in manners courtesy of Virginia Mercereau on July 31, 1929.

According to the press, the incident went something like this:

“Waiting for a street car, baby?”

“I’m going shopping,” Mercereau replied.

“Can I go along,” he replied, thinking he was in with a shot.

“You not only can, but you will,” yelled Mercereau, followed by a right hook, a headlock, and a swift, firm blow between his shoulder blades.

Duffy was down, out, and later booked at the nearest station.

As he was being booked, he demurely asked Mercereau what her profession was – “Why, I’m claimant to the title of world’s middleweight woman wrestler,” was the reply. “Look up my record.”

All Duffy could muster as he was jailed was, “I wish I had.”

“A Lesson for Gay Mashers from the Woman Wrestler.” Coverage after the arrest of George Duffy, 1929.

Exiting the Business

That career rethink, which came around 1930, was essentially the end of the career of Virginia Mercereau. Finding herself facing an insurmountable headwind in the wrestling business, Marie Didderich decided to drop out of wrestling and move into health and fitness.

Newark, Ohio, was her final destination, though it was erroneously reported as Newark, New Jersey. The mistake was understandable – after all, the women’s champ would always be in the biggest and brightest cities.

But this wasn’t Virginia Mercereau; this was Marie Didderich. Marie wasn’t the women’s champ – she was the manager of the John P. Glass Health Service.

While working with the company, she still found time to perform as the “Golden Accordion Girl,” Virginia Mercereau, usually for the annual Fall Fashion Show.

An ad for the annual Fall Fashion Review, including the “Golden Accordion Girl,” Virginia Mercereau

A Replacement Arises

But don’t worry. The Women’s World Middleweight Championship wasn’t abandoned – someone else just appropriated it. The culprit was one Mae Meyers of St. Paul, Minnesota. The February 9, 1936 edition of the Wisconsin State Journal notes that Miss Mae Meyers “defeated Miss Virginia Mercereau some time ago to win the women’s crown.”

According to the Capital Times in Madison, Wisconsin, on February 7, 1936, Mae Meyers – who was defending her hard-earned championship against the latest contender, Stella Brown – apparently “won the championship from Virginia Mercereau by overcoming a 30 pound weight advantage and winning the match in straight falls before a capacity crowd in Seattle, Washington.”

I have found no evidence of this bout and doubt it ever occurred.

Why Seattle? I guess 1936 was a simpler time before the success of intercontinental airfare and the creation of international phantom title changes. Regardless of the particulars, Marie Didderich had left the business for good – she was born a generation too early.

In the next decade, women’s wrestling would gain a greater deal of acceptance and credibility – particularly on the back of talents like Mildred Burke, Clara Mortenson, and others. That credibility was made official with the sanctioning of the first “official” Women’s World Championship in 1937.

Happily Ever After

But while Marie was out of wrestling, she was just getting started living her happily ever after. She continued her successful role in healthcare for several years before upping sticks and heading west.

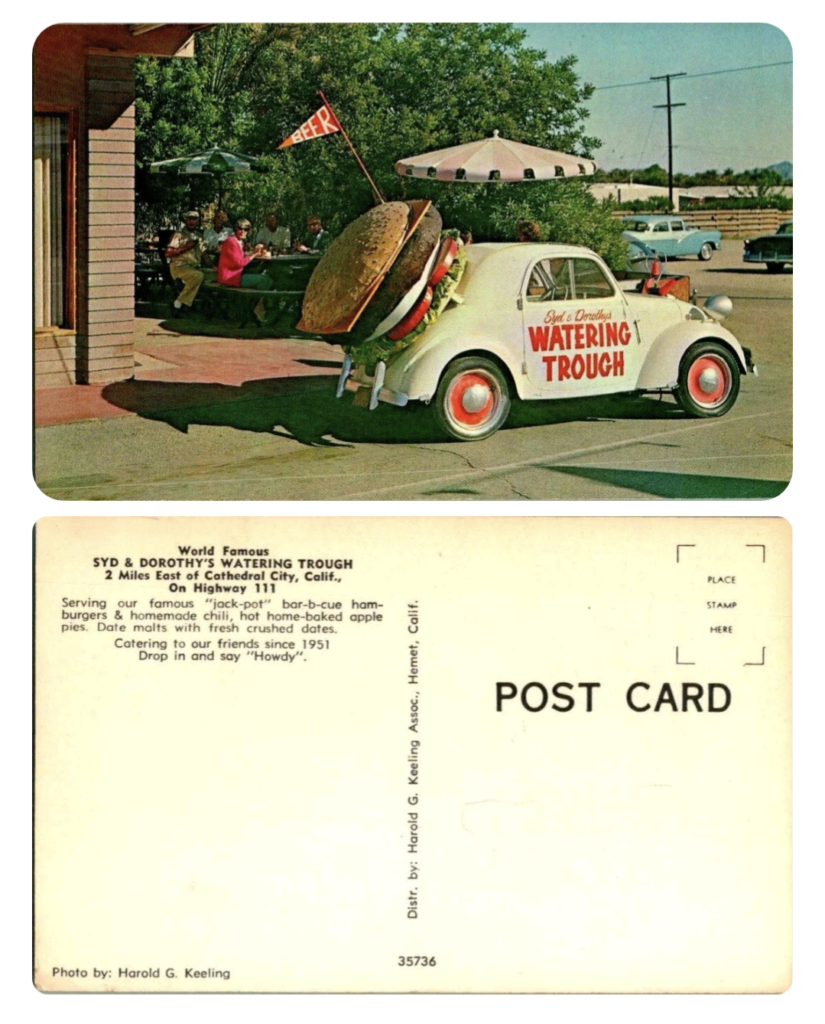

In 1943, Marie found love, marrying Edward Frisby, a Utah-born businessman in Los Angeles, before finally settling in the deserts of Southern California – namely the affluent Palm Springs community. There, Marie would turn from brutality to hospitality, opening a successful restaurant, the Watering Trough in nearby Cathedral City. The hangout was popular for its hamburgers, with the couple eventually cashing out sometime around 1963.

Late 1960s postcard from the Watering Hole, Cathedral City, California. This was after Marie and Edward Frisby sold.

Marie (sometimes spelled Maree) spent her remaining years supporting her family’s artistic endeavors. Marie Frisby died on April 26, 1980, at her longtime residence in Palm Springs. Upon her passing, there was little discussion of her past life in basketball, wrestling, or vaudeville.

For a woman who experienced such a dramatic public humiliation in her professional and romantic life, Marie Didderich never let life get her down. From humble Midwestern beginnings, she let her gifts guide her and never surrendered – even when personal tragedies almost won.

While undoubtedly chaotic, her grace, humility, and take-no-shit attitude is apparent throughout. When a roadblock emerged, she took a designated detour – or created one for herself.

But it was those Midwestern values that kept her centered – and eventually helped steer her to a happily ever after – selling the best hamburgers under the Palm Springs sun. And throughout – until the very end – she was surrounded by her loving and devoted family.

The Legacy of Virginia Mercereau

Women’s wrestling has enjoyed a great surge in popularity in the 21st century, largely thanks to stars like Trish Stratus, Lita, Natalya Neidhart, and others. But the Attitude Era also brought the Fabulous Moolah and Mae Young, two stars of several previous generations, back to the fore.

And with that acquaintance sprang a more serious study of the history of women’s wrestling, with countless works in the ensuing decades. Beyond the WWE-produced autobiographies, there is the exceptional Sisterhood of the Squared Circle: The History and Rise of Women’s Wrestling by Pat Laprade and Dan Murphy, for example. Other historians have taken closer looks at influential stars, like John Cosper’s The Girl With The Iron Jaw: The Amazing Life of Mars Bennett. For those who prefer film to print, there’s the 2004 documentary Lipstick & Dynamite, Piss & Vinegar: The First Ladies of Wrestling.

I could wax poetically about the merits of these works and many others, but let me try to stay on track with this narrative.

While these efforts are undoubtedly commendable (and excellent), they are limited in their scope. Not because the researchers were lax but rather because there is always more to discover in the world of wrestling. Any attempt at a fully comprehensive account on the history of any facet of the wrestling business is doomed to failure because the compiler would die long before they could consult every resource and get every angle.

Even with Virginia Mercereau, there are many stories to be told of this remarkable woman. The fate of Leroy Bringham, AKA “Al Ketchel,” for example, is of particular interest. It’s likely local researchers can shed much more light on this facet of her story – one of the limitations of online newspaper archives.

So what is the legacy of Virginia Mercereau, middleweight women’s wrestling champion? Unfortunately, not much. Sure, there were a few “remember when” posts through the years and a 1972 television show in which she is mentioned, but the name Mercereau is effectively lost to time.

And that is a major shame. She was a woman ahead of her time – ten years to be precise. With the end of the 1930s came the rise of Mildred Burke, Mae Young, and other women grapplers who were allowed to star in their own right.

Gone were the days of “seedy” intergender matches, and in its place was sanctioned, sterile competition between two women. It’s in this period that Virginia Mercereau would have excelled, but she was born too soon.

But wrestling’s loss was life’s gain, with the spirit of Marie Diderrich proving insurmountable, regardless of the odds. No matter where she turned her attention, she succeeded. From basketball to wrestling to vaudeville and business, Diderrich never quit.

Her reward for that dogged determination was a life full of love. Upon her passing, scantly, a word was mentioned of her past life as world champion, but it didn’t matter. Even without the credit she deserves, there is only one word to describe Marie Diderrich, “Ketchel,” Frisby, Virginia Mercereau, or whatever name you prefer:

Remarkable.

RELATED LINK

Virginia Mercerau: Early women’s champ bamboozled away from ring