In 1977, the Masked Superstar committed the dastardly deed of cutting the dark hair of popular Paul Jones as part of their feud in Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling. Watching on TV in North Carolina, a teenager named George South was crestfallen. So he took an appropriate step to mourn the plight of his idol.

“I was so heartbroken over this that I went and got an old pair of scissors and I started cutting batches out of my hair,” South said. “I even went and cut my own hair just so I could look like Paul. You’d get locked up for stuff like that nowadays.”

That’s the bond that South felt with “No. 1,” who died on April 19 at 75. Theirs is a story of hero worship, school truancy, hurled hot dogs, and pranks in and out of the ring.

More than anything, though, the connection demonstrates the power of wrestling and how Jones passed on life lessons to an impressionable boy who applied them years later in training wrestlers like Tessa Blanchard, Scott Dawson, and Cedric Alexander,

“The only reason I want to do it right is because I don’t want to hurt Paul,” South said of his training schools in North Carolina. “He meant so much to me that I don’t want to hurt his legacy. I want to pass it along.”

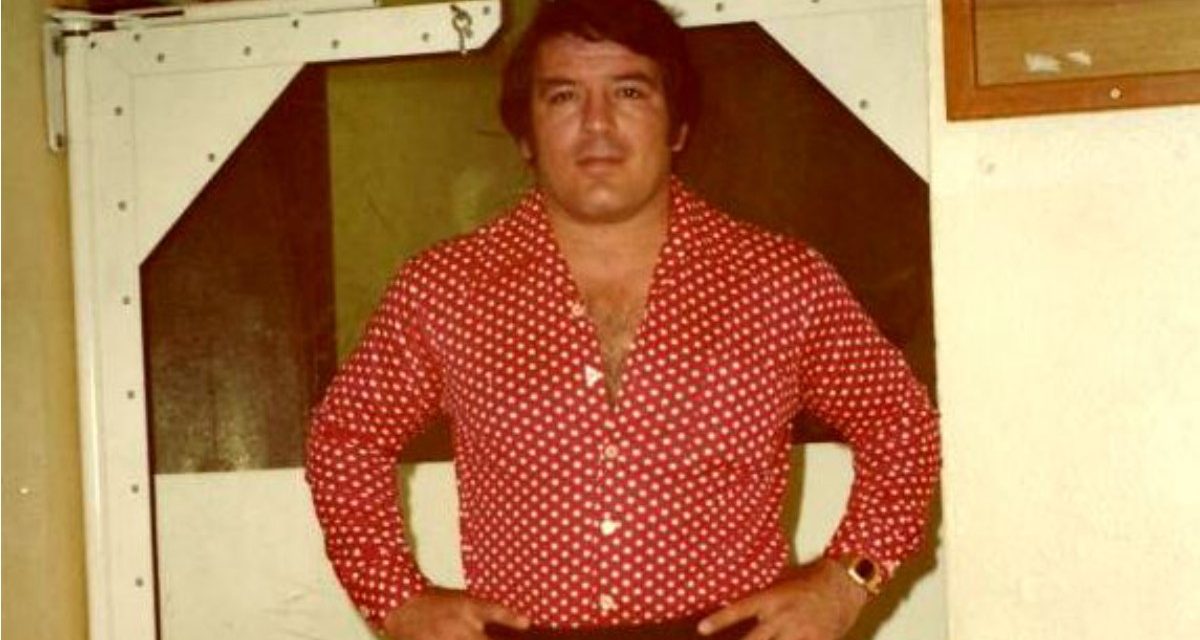

Paul Jones and George South chat. Courtesy George South

LOVE AT FIRST SIGHT

South lost both his parents at a young age and was an elementary student in Gastonia, North Carolina, living with a brother and other relatives when he chanced upon TV wrestling one Saturday afternoon. There, in black and white, was handsome Paul Jones, the smallest man in a match with Wahoo McDaniel against Gene and Ole Anderson.

“Man, I just fell in love with Paul Jones,” South said. “I didn’t know what I had just found. I just know that it really got my attention and I was hooked. I really, really believed that tough as Wahoo was, if he could just make that tag to Paul, everything was going to be OK.”

South’s first live show was in September 1975 at Charlotte Memorial Stadium. Imagine his delight in the pre-barricade days when fans could hang near the dressing room or stand next to a wrestler — say, Paul Jones — who was watching a preliminary match. The first interaction between the two was brief, but South started hitting the Charlotte Park Center every Monday hoping to see Jones.

His pursuit of Jones was so intense that veteran Johnny Weaver played a rib on the youngster. Asked if Paul Jones would be at the Park Center, Weaver replied, no, the only Jones that night would be Rufus R. Jones, the powerful black wrestler. “I remember it like it was yesterday,” South said. “Here I was maybe 10 years old, I’d be crying, standing there thinking I messed up. Of course, later on, Paul would come out and it would make everything better.”

Jones had his own way of chasing away South. He asked the kid to fetch him a cup of coffee. Then he disappeared. Later, as South became less of a pest and more of a friend, he asked Jones about it. “I went and got you coffee about 300 times and spent my own money and came back and where were you at?” Jones’ response: “I did that to get away from you.”

“That was my childhood,” South laughed. “There was nothing else. There was no dating in middle school, high school, going off with the guys. It was, ‘Man, I have to see what Paul Jones is doing.’ I was stalking Paul Jones before it was cool to stalk people.”

At home, South mowed lawns, then raced to Piedmont Newsstand in Gastonia to buy wrestling magazines that had cover pictures of Jones. He carefully clipped them and kept them in large scrapbooks. In school, South fancied himself as the next Paul Jones. Instead of his given name, South signed “Paul Jones” on his homework. “You tell me how whacked out this young boy was? Even in yearbooks, I signed my name ‘Paul Jones,’ ” South said with a chuckle. “Paul got the biggest kick out of that.”

THE TURN

In late 1978, Jones committed a deed even more despicable than the Masked Superstar’s tonsorial work. He turned bad guy on tag team partner Ricky Steamboat in a battle royal in Charlotte, right before South’s eyes. Jones always insisted that a careful review of the evidence revealed Steamboat turned on him.

No matter. South was loyal. He stuck with his man to the point that he assumed his Paul Jones identity in school, only now as a villain. It sounds silly in retrospect, South admitted, but hero worship is not something to be tossed away casually.

“I thought, ‘Well, OK, I’m Paul Jones.’ You would not believe how many times I got sent home from school and I blame Paul. ‘I hate doing homework, I hate saying yes, sir. I’m not doing anything I’m told to do because I’m a heel.’ That’s the influence that Paul Jones had on me.”

When Jones returned to the Park Center in his new, nefarious persona, South was there to cheer him, possibly his only supporter in a packed house. Seated in the floor section, South brought with him a handmade poster on which he had marked, in big letters, “Paul Jones is Still No. 1.” When South went ringside, Jones saw the poster, grabbed it, and started parading cocksure around the ring.

“He gave me the sign, gave it back to me, and it wasn’t five seconds later, somebody threw a hot dog at me. I’m like 13 years old, this mustard is flying,” South said. “Next thing I know, somebody poured beer on me. They’re throwing paper at me, they’re throwing popcorn at me, I’m fixing to get killed.” Security guards escorted him away for his own safety, but South said he learned a lesson about wrestling. “That’s how much heat Paul Jones had by turning on Steamboat.”

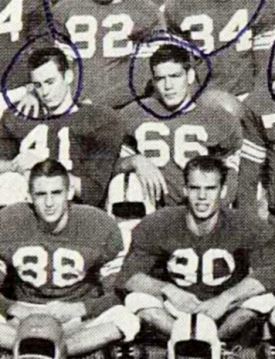

No. 1 was No. 66 in this 1958 shot of Alfred Frederick (Paul Jones) on his high school football team in Port Arthur, Texas. (Steven Johnson collection)

Within a few years, South was starting up his own pro career. Jones gave his some tips, though he refused to share his nickname. South wanted to wrestle as “No 1,” like his hero. “Paul said, ‘No, you’re not. There’s only one No. 1 and you’re looking at him. You can be ‘Mr. No. 1.’ ”

South worked his way up from some independent shows in 1982 and 1983 to Georgia Championship Wrestling and then Jim Crockett’s Mid-Atlantic promotion, headquartered in Charlotte.

South never got a chance to wrestle one-on-one with Jones, who transitioned from a full-time wrestler into a manager by 1982. So he did the next best thing — take a beating from members of Jones’ “Army,” like Abdullah the Butcher and the Barbarian. South asked Abdullah, for example, to hurl him out of the ring toward Jones, so Jones could take a swing at him.

After a few encounters, Jones grew weary of that angle,

“It was almost like I was chasing him so he could punch me. I think it got to where he was so tired when they would throw me out, he would start walking the other way,” South said.

A MORE MATURE RELATIONSHIP

Jones owned a car garage in Charlotte and South dropped by as a matter of routine. One day, Jones pulled out a gold watch he received from Crockett circa 1975 when he won a legitimate postcard contest naming your favorite wrestler.

He tossed the watch to South, who was sitting with his one-year-old son Garrett. Here, he said, you can have it. “I started crying. I’m an older man; I’ve got kids and a child that I’m holding and I started crying,” South said.

Cue Jones and his dry wit. As South got ready to leave, Jones asked for the watch. “I can’t give you that watch. It means the world to me,” he said. Dejectedly, South returned the watch to its rightful owner. “My emotions were like a rollercoaster. Here I was happy and crying and now I’m ready to run over Paul with my car.”

Then Jones started laughing. He was working South, just like he worked fans since his debut in 1964 in Texas. When he gave the watch to South a second time, his young friend took no chances. “I got in the car, rolled the windows up, and locked the doors. I didn’t even say bye. To this day, I still have that watch,” South said.

As he became an established wrestler, South said he developed a new understanding of Jones’ skill in the ring. An example — South came across a match between Jones and former world champion Jack Brisco in which the two seemed to wrestle backwards, working holds from the right side instead of the left, as young wrestlers learn. Aha! South thought — I found a flub.

Not so quick. Jones said he and Brisco did that intentionally, to amuse themselves and show wrestlers peeking at them from the locker room that it could be done. “I learned a valuable lesson from Paul that day. He said, ‘If you’ve got two people that know what they’re doing, you can do anything they want to do.’ They weren’t doing it wrong; they were doing it right. They were doing it the opposite way. The fans didn’t know the difference, of course. But what a lesson that was.”

When they both lived in Charlotte, the two went to lunch frequently and South nagged Jones about keeping his doctors’ appointments. He had less success integrating Jones as his manager into shows he ran in the Mid-Atlantic. Wrestling on the floor, South hooked an opponent in a full nelson and stood him in front of Jones. The idea — Jones would throw a punch, the opponent would duck, and the blow would connect on South’s noggin.

Jones balked. “So me and him are arguing at ringside,” South said. “The fans think, ‘What are you doing?’ He said, ‘No, it won’t look right. It ain’t got nothing to do with the match.’ Here Paul is trying to be all professional and I’m just wanting to take a punch from him.” Of course, he added, Jones was correct. The punch did not fit in the context of the match.

Jones and South.

PASSING OF THE GUARD

When Jones moved to Florida, South paid him a visit and kept in touch with him after Jones settled for good in Georgia. South bugged his friend for a spare ring jacket, but Jones gave most of his stash away at charity golf tournaments and other events. So South had a friend fashion one with red, white, and blue down the sleeves, just like an authentic “No. 1” model. He still wears it to the ring. “That kid’s always trying to imitate me,” Jones mused.

South also asked Jones to write the dedication to his 2012 autobiography, Dad You Don’t Work, You Wrestle. Jones was about as enthused as when South tried to get him to throw a sucker punch, which is to say not at all. “I’m going to write a bunch of good stuff about me and how I was your favorite wrestler and I’m just going to sign your name to it,” South told him. That time, Jones backed down.

As a trainer, South said he’s kept Jones’ lessons uppermost in his mind. He thought of Jones when Cedric Alexander sent a batch of autographed trading cards in appreciation for all that South taught him on his way to the WWE cruiserweight championship. “That’s the greatest reward to me and it’s almost a reward to Paul, because I tried to do it right because Paul did it right,” South said.

The last time South saw Jones in person was at promoter Greg Price’s NWA Legends Fanfest in 2016. Jones was a regular at the annual events, and the final greeting between the two will linger with South for a long time.

“I shook the man’s hand 500 times, but at this last fanfest, you could almost see the nervousness in me. I was standing back a little bit because I was still a fan. I was still this little kid that was meeting his hero.”

RELATED LINKS