Howdy all, and welcome back for another edition of Card Exam! This week I decided to look back at one of wrestling’s most famous arenas – the Dallas Sportatorium. The iconic (and dilapidated) arena stood at the intersection of Industrial Boulevard and Cadiz Street in downtown Dallas and is best remembered as the home arena of the Von Erich family.

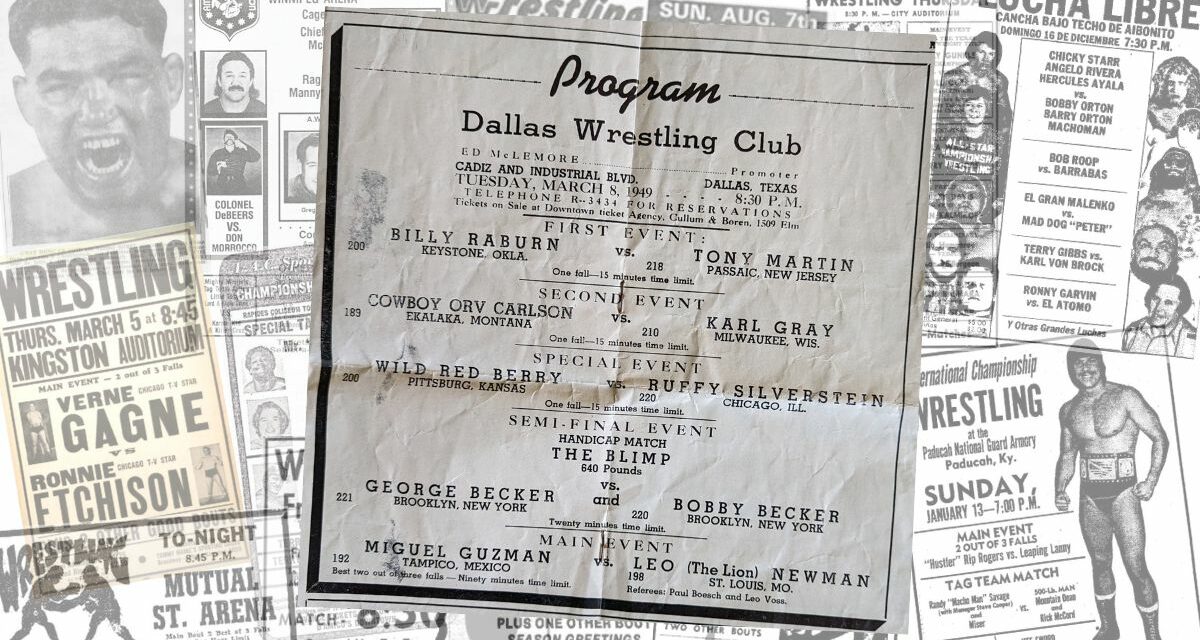

Here’s the card for the evening, presented by the Dallas Wrestling Club under the direction of promoter Ed McLemore and matchmaker Karl “Doc” Sarpolis:

March 8, 1949, at the Dallas Sportatorium, Dallas, Texas

Bell time 8:30 PM

- Billy Rayborn vs. Tony Martin fought to a time-limit draw

- “Cowboy” Orv Carson defeated Karl Gray

- Ruffy Silverstein defeated “Wild” Red Berry

- The Becker Brothers defeated Martin “The Blimp” Levy in a 2-on-1 handicap match

- Miguel “Black” Guzman (c) defeated Leo “the Lion” Newman 2-falls-to-1 to retain the Texas Heavyweight Title

So, why did I choose this event? I want to say it was due to the impressive talent on the card (it’s pretty good) or the historic building, but in reality, it’s because I own the program for this card. And while that sounds great in principle, it’s been something of a misstep because this particular evening is completely missing from the newspaper records.

But records being records (and deadlines being deadlines), I knew this was a compelling card and an equally compelling cast of characters, so I persisted. I think “hero” is the term.

The Dallas Sportatorium

Anyways, by 1949 the Sportatorium was firmly under the control of promoter Ed McLemore. McLemore had started at the concessions when the building first opened in 1935 and had worked his way up to owning the building (and promotion) after 1940, with many of his wrestlers supplied by Tulsa wrestling kingpin, Sam “Tex” Avey and Morris Seigel in Houston.

The year 1949 was a big one for wrestling, with the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) founded in Waterloo, Iowa, the previous summer. The fall would also see wrestling in Texas enter the NWA fold, with Avey and McLemore present, bringing the group’s fledgling membership to 20 members. But earlier in the year this dynamic had not shifted, and Texas wrestling was operating under its normal circumstances, relying on talent from the likes of Fred Kohler, AL Haft, Jack Pfefer, and others.

The opening bout between Billy Raborn and Tony Martin seems rather blah, but it hides a rather famous wrestling legend – and it’s not Billy Raborn (sorry, Billy).

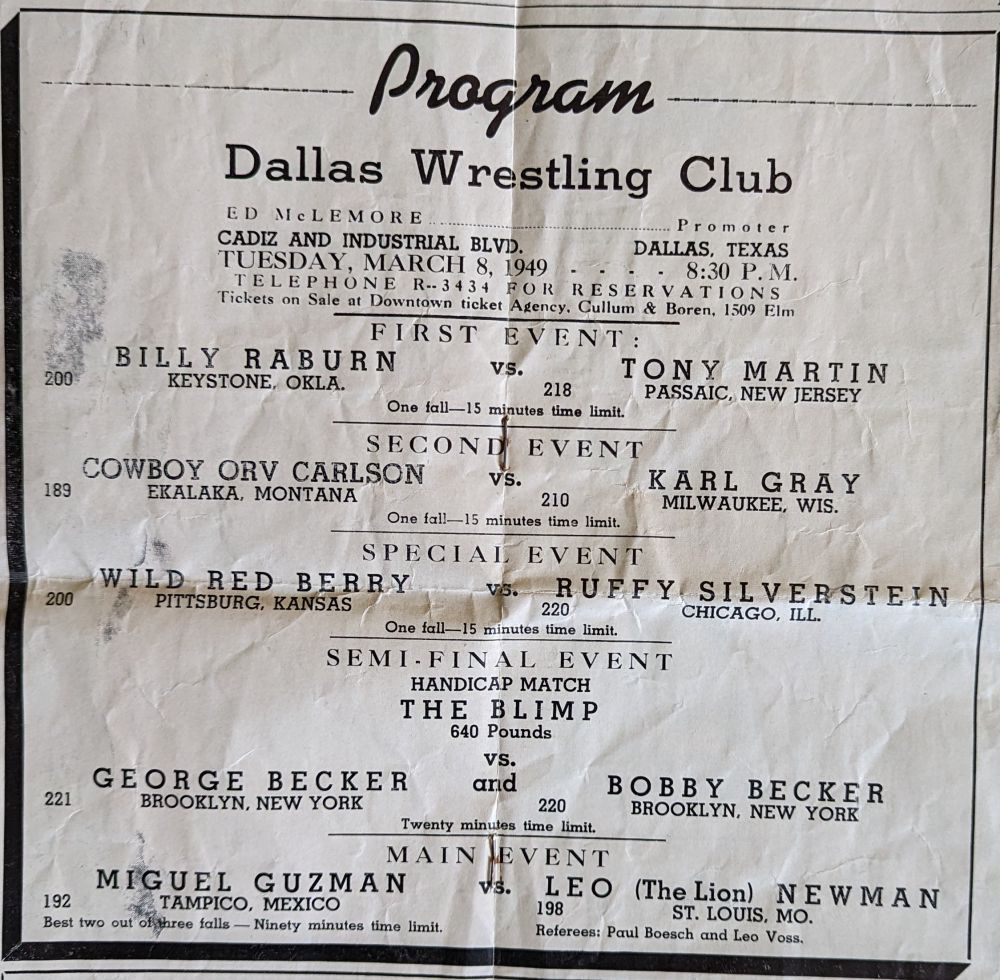

Tony Martin is probably better known by a couple of the other names he used in his 40+ year career. Chief amongst those names sends shivers down the back of Southern babyfaces everywhere: “The Assassin.” Yep, Tony Martin was none other than Tom Renesto Sr., better known as Assassin #1 with Jody Hamilton.

The Assassins

The Assassins were a hit from the start, not just with the fans. Hamilton and Renesto, too, sensed the chemistry, as recounted in Hamilton’s excellent 2021 obituary by Greg Oliver:

“Seven or eight minutes into the match, I knew we had a great combination together because he anticipated things that I was going to do, and I could anticipate things that he was going to do, so consequently, we were always in the right place at the right time,” he stated.

All combined, Hamilton and Renesto would win more than 30 different versions of the world tag tiles before disbanding in the early 1980s.

But Renesto also took on other famous names of other stars, namely those of Al Lovelock and George Bollas. Lovelock and Bollas had found fame as the “Great Bolo” and “Zebra Kid” respectively, with Renesto taking on the roles for differing reasons – first as a partner to Lovelock as the masked “Bolos” and a as a replacement for Bollas when he and Jack Pfefer had an inevitable falling out over pay.

Jumping back to Billy Rayborn, he is no slouch, either. Born Inman Raborn in Georgia in 1917, he would win the NWA Texas Junior Heavyweight Title multiple times and even win a World Light Heavyweight Title claim in 1941. And Rayborn proved he was more than capable as he and Martin battled to a 15-minute time-limit draw.

The second preliminary pitted Cowboy Carlson and Karl Gary in another 15-minute affair. “Cowboy” Orville Carlson was another popular light heavyweight who would find his greatest fame in New Mexico and Amarillo, where he was a multiple-time tag champ with Dory Funk Sr. Carlson was also a real cowboy, residing on a cattle ranch in Montana once his career wound down.

For his part, Karl Gray (really Karl Rosenstein) was another popular act in New Mexico. He was himself a one-time New Mexico Light Heavyweight titleholder, although his claim would last just a month in mid-1947. In the end, the superior skills of the fan-favorite cowboy prevailed.

This card also features a “hum-dinger” of a special event: Wild Red Berry versus Ruffy Silverstein in (another) 15-minute affair. Red Berry is a name that continuously pops up on mid-century results – especially in the American West.

Wild Red Berry as a manager

Ralph “Wild Red” Berry is one of the most interesting characters in wrestling because of how he changed the game regarding interviews. Never a big wrestler in stature, Berry made up for it with his mouth, becoming one of the sport’s earlier (and best) managers once his in-ring career wound down.

It was his tongue that kept him on top in the California territory, as best demonstrated in this fascinating biography by the equally-great Steve Johnson in 2010:

“My strategy is that of compelling them to proceed from a state of bewilderment and complete uncertainty to a disturbing sense of inferiority, putting them thus in awkward, perplexing, and vexatious situations on the horns of a dilemma. This is possible through my great depth of intellect, integrity, heroic boldness, leonine courage, scholarly mien, and alert perception.”

His opponent, Ruffy Silverstein, is another ever-present name during this era. Ralph “Ruffy” Silverstein was a Chicago-born grappler who found considerable success wrestling for Al Haft, Fred Kohler, Harry Light, Sam Avey, and almost every other major promoter of the period. Silverstein was a college wrestling champion at Illinois. He kept that streak alive by winning the AWA World Heavyweight Title (the Chicago version) twice.

The Blimp

The semifinal matchup features a familiar Jack Pfefer “freak” – Martin “The Blimp” Levy. Levy had been discovered in the early 1930s by Pfefer at Coney Island, where he was working in a freak show – or at least that’s the story Pfefer chose to tell. Pfefer loved his freaks, once telling a reporter that:

“You can’t get a dollar with a normal-looking guy, no matter how good he can wrestle. Those birds with shaved, egg-shaped heads, handlebar mustaches, tattooed bodies, big stomachs – they’re for me!”

Levy was never good; in fact, one paper described him thusly: “As a wrestler, he is very fat.” By 1949 he was effectively useless in the ring, relying upon his weight – and nothing else – within the squared circle. Writing in the program for March 8, 1949, Sportatorium card highlighted his limited mobility, stating that Levy “could no more place a dropkick as he can train down to 200 lbs. and win the junior heavyweight title.”

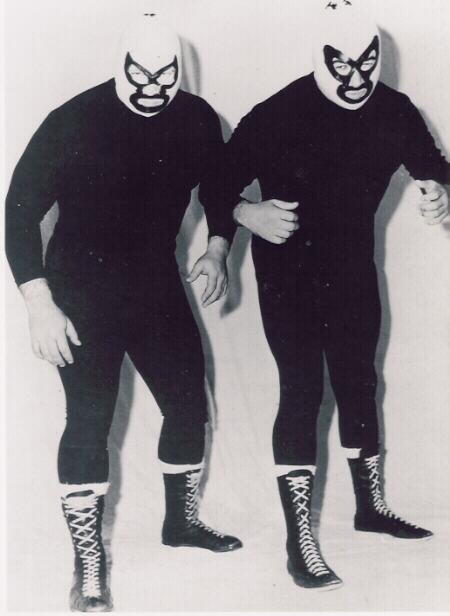

The selling point for the semi-windup was a handicapped match, with the Blimp taking on not one but two Becker Brothers: George and Bobby. The brothers were a longstanding and popular tag team comprised of one real “Becker,” George, and a kayfabe brother, Bobby (real name John Emerling). Levy would need to pin both brothers within the 20-minute time limit to win.

The Beckers. Photo courtesy Gary J. Grieco

George is easily the most well-known of the two, due in no part to a career in the business that spanned five decades. Perhaps his most famous tag partner was Johnny Weaver, the master of the “Weaver lock.” The two captured the NWA Mid-Atlantic Tag Team titles five times, notably feuding with the likes of Swede Hansen and Rip Hawk. George Becker was also the husband of Joyce Grable, one of the biggest names in women’s wrestling during the territorial era (the first Joyce Grable, not the one that wrestled in the 1970s and ’80s).

Bobby Becker is less well-known due in part to a much shorter career than his “sibling.” Emerling bounced around from territory to territory and promoter to promoter over a 17-year career in which he mainly competed under the name “Hans Schwarz.”

The name “Bobby Becker” was certainly on the mind of the Dallas fans as they headed to the Sportatorium on Tuesday evening, as he had appeared in the televised bout of the previous evening’s mat card. Becker and Black Guzman faced off on WBAP-TV’s coverage of the Northside Coliseum show – though the result is unknown.

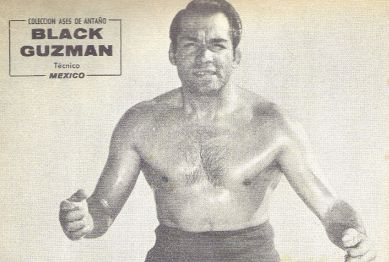

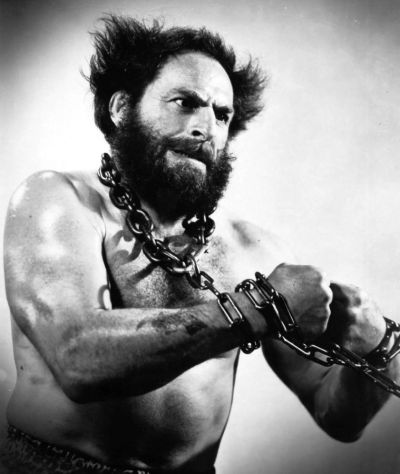

Black Guzman from a Mexican wrestling magazine

Speaking of Black Guzman, he is in the main event for the evening – a two-out-of-three-falls match with Leo Newman for the Texas Heavyweight Title. Newman, more commonly known as “Leo the Lion,” had already held a claim to the World Heavyweight title in Colorado a few years prior but now had his eyes firmly set on Miguel “Black” Guzman and his Texas Heavyweight Title.

The two had initially clashed a week before, with uniformed police required to break up a near-riot when Guzman struck an officer trying to break up the chaos that spilled outside the ring. Guzman, born Miguel Guzmán Huerta in Hidalgo, Mexico, was one of Mexico’s first breed of superstar luchadores.

Guzman was wrestling royalty, with his siblings and descendants among the who’s who of Mexican wrestling. His brothers, Pantera Negra and El Santo, are legendary, with Santo as one of the most important figures in the sport’s history. But he was no pushover himself. Black Guzman (so named for his dark complexion) was a regular in the Texas scene by the 1940s and had first established himself as Texas champ in August of 1947.

Leo Newman

Ultimately, Guzman would retain his title in a feisty affair, beating Newman 2-1 on falls, with the final fall through disqualification. It was an unsatisfactory finish, but it kept the program going.

Ed McLemore’s stewardship of the Sportatorium would run until 1969 and his death, with wrestler Fritz Von Erich taking over the territory after that. But McLemore’s tenure as not without controversy, including aligning with Jack Pfefer in 1952-53 in a wrestling war that would famously see a gun pulled on Pfefer, leading to his quick retreat from the Dallas territory.

Texas wrestling strikes at the very heart of the North American wrestling landscape, and this card is an excellent example. Despite no major “heavyweights” beyond Levy, the card was full of tough, no-nonsense grapplers that provided exactly what fans everywhere want: fast-paced action, colorful characters, and most importantly, blood and violence in spades.

Now I reckon I’ll sign off until next time, partners.

RELATED LINK