The dictionary tapped out. Threw in the towel. Gave up the ghost. When “Wild Red” Berry entered the study, the dictionary cowered at the end of the bookshelf, hoping that he would direct his interest somewhere else — to Shakespeare, maybe. No such luck. Berry took the dictionary, whipped it into the turnbuckle, dropped an elbow on it, and clamped it in his famous Gilligan twist submission hold. The dictionary never had a chance. It wasn’t a fair fight, not by a long shot, because in the annals of professional wrestling, Berry was the undisputed champion of the no-holds-barred Linguistic Death Match.

As a manager, “Wild” Red Berry knew it all.

Ralph “Wild Red” Berry was a dichotomy: a small man in a big man’s game, a frequent scoundrel in the wrestling ring who was much admired outside it, and a middle school dropout with a vocabulary that would turn Merriam-Webster green with envy. Take this sample from 1952, when Berry explained what he planned to do to anyone who challenged his longstanding status as a top-of-the-card star in California.

“My strategy is that of compelling them to proceed from a state of bewilderment and complete uncertainty to a disturbing sense of inferiority, putting them thus in awkward, perplexing, and vexatious situations on the horns of a dilemma. This is possible through my great depth of intellect, integrity, heroic boldness, leonine courage, scholarly mien, and alert perception.”

Berry’s accomplishments as a wrestler and manager during a career that spanned more than 40 years have earned him a place in the 2010 class of the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in Amsterdam, N.Y., which is holding its annual ceremonies this weekend. It’s a shame that Berry, who died in 1973, won’t be around for speechmaking time, because to him, words were oxygen.

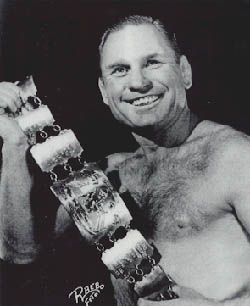

Red Berry poses with a title belt in a publicity photo. Courtesy Chris Swisher

“He’d go out there and build up a head of steam just as soon as he could, and start fighting with the people,” said veteran star Frankie Cain, still chuckling at the thought more than half-a-century later. “He never shut up. I mean, he’d talk to the people from the beginning of that match to the end of that match, always raising hell with them.”

The pride of tiny Pittsburg, Kansas, Berry was a banty rooster of a fighter at 5-foot-8. He held the National Wrestling Association light-heavyweight crown nine times from 1937 to 1947, and was enough of a draw that he could still headline the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles against Edouard Carpentier at the age of 52.

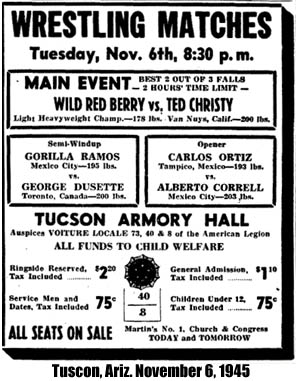

The Kangaroos, Roy Heffernan and Al Costello, with their manager, Red Berry. Courtesy Chris Swisher

When his wrestling days were over, Berry made a seamless transition to managing, donning a derby and lending his verbal skills to the Fabulous Kangaroos, Hans Mortier, Gorilla Monsoon, and a host of other baddies, primarily in the World Wide Wrestling Federation.

Whatever his role, his gift of gab set him apart from the pack. “Let these hams primp their feathers and strut their plumes,” he bellowed in 1954. “I will proceed to maltreat and obliterate them. I will turn loose such terrific voltage and velocity and elliptical trajectory that when it lands on the cleft of the chin it will tear loose their medulla oblongata from the pericranium, cure them of chronic dandruff and knock out four of their impacted wisdom teeth.”

No wonder that Time magazine once decided that Berry had perfected a new and tortuous maneuver — the “tongue” hold.

Born in 1906, Berry had a difficult childhood in Kansas. His father left the family, and Berry quit school before he finished eighth grade to work in a coal mine and support his mother and two younger siblings. “He talked about crawling in a hole about the size he was with a bag and a pick, and filling it up and backing out of the hole,” said his son, James, a retired Army lieutenant colonel with the military police. “One day, it caved in on him and he couldn’t go back because he was claustrophobic.” Berry’s long-windedness was more than a gimmick, though. It was his way of life, and the basis for a story of personal self-improvement that he spread at speaking engagements across the country.

Berry painted a local YMCA in lieu of paying dues, and started boxing as a teenager. But his hands were brittle, and when he broke both of them, he decided wrestling might be a better fit.

While his first recorded match was in 1926, his son said that Berry was wrestling and working the carnival circuit well before that, trying to stay a few minutes with all comers for spare change. Berry stayed mostly in the Midwest during his early career, though he ventured to the Pacific Northwest in 1930 and eventually landed in Southern California, where he feuded for years with “Dangerous” Danny McShain (who, fittingly, is being inducted into the PWHF in the same class).

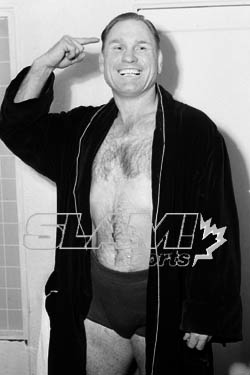

Red Berry demonstrates a grappling pose. Courtesy Chris Swisher

From the start, Berry was a showman of the first order. He cemented his reputation as a “wild man” with a botched publicity stunt in Kansas City, Kansas, where promoter John Hatfield convinced him to slip into a leopard suit and swing from a courthouse tree as a demonstration of agility and resourcefulness. Law enforcement authorities were unimpressed, Berry told reporters in later years, and hauled him away for disturbing the peace.

His finisher was the Gilligan twist, a double arm pull with a knee to the back of the neck that he originally called a guillotine, until an announcer flubbed the call. But Ted Tourtas, whom Berry took to Arkansas in 1941 to work as a masked man, mimicked his mentor’s most common move during a recent interview. Tourtas stood up, and shrugged his shoulders while waving his arms front and back in an ‘I’m-riled-up’ fashion. “That was it,” Tourtas laughed.

In fact, Berry lived to play to the crowd, whether he was wrestling as a fan favorite or a sneaky, pint-sized heel. Blinding an opponent by tossing a foreign substance in his eyes has been a staple of wrestling villainy; Berry perfected the art in St. Joseph, Missouri, in 1932, flicking powder in the face of George Lapel for an easy win.

A bloody Gorgeous George Grant and his partner Red Berry. Courtesy Chris Swisher

Working in Los Angeles in the 1950s, he quarreled with announcer Bill Welsh, whom he claimed was badmouthing his ability as a wrestler. With all the expansive outrage he could muster, he refused to set foot in the ring at Hollywood Legion Stadium until Welsh was canned.

“We started gathering signatures of fans who wanted me to stay and we got at least 50,000 names. It was unbelievable,” Welsh remembered in a 1964 interview. Undeterred, Berry decided to enter battle wearing a pair of earphones that he claimed was specially designed to pick up Welsh’s aspersions during the match. “It ended when one of his opponents smashed it over his head,” Welsh said.

As referee Tommy Fooshee of Texas concluded: “He was a little guy, but he could get out there, and in five minutes he’d have the place upside down.”

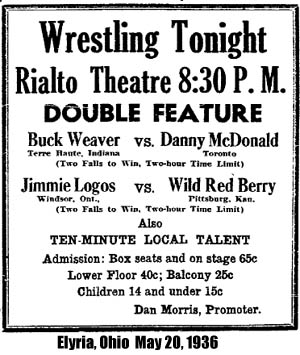

“Wild” Red Berry, smarter than the average wrestler. Courtesy the Chuck Thornton Collection

Merriment and mirth-making notwithstanding, Berry was serious about his dedication to lifelong learning. In 1947, he suffered a serious arm injury that put him out of commission for more than a year. He had a plate inserted in his arm, which became infected; his son James recalled that doctors wondered whether “Wild Red” would lose his arm.

Recuperating in a hospital, he started to read a Bible. And as he read and read, he found he was blessed with a near-photographic memory. On his own, the clowning redhead studied religion, literature, grammar, and the works of the world’s great thinkers. While other wrestlers might have tucked a bottle of gin or a pack of smokes in their gym bags, Berry carried with him two small, loose-leaf notebooks. In one, he recorded his observations; in the other, he jotted down words, poems, and inspirational thoughts to commit to memory. Eventually, he collected his favorites in a paperback book that he called the “Anthology of Philosophy.”

Berry’s way with words was an ideal fit for a new medium called television, which relied on a heavy diet of wrestling to fill its airwaves. “He was extremely popular in the ’50s in California. He could not go anyplace without being mobbed,” James Berry said. “He was there at the start of television. It was perfect timing. He was on TV in Hollywood, during the ’50s, five or six nights a week.” With his high profile and gilded tongue, Berry became a fixture on the lecture circuit, balancing a double life as a man of letters and a man of mayhem, as he explained to Chicago sportswriter David Condon in 1962:”I picked up the Bible and developed faith I didn’t know I had,” Berry told Iowa sportswriter Al Ney in a reflective moment in 1957. “It was then that I read everything I could on faith and philosophy … I try to lead my life in such an ethical manner that I can go before the courts of public opinion with a clean hand and to correct my many weaknesses and do something of a charitable nature every day if only to give a pleasant word or smile as I go along my way.”

“I go into a town and address high school assemblies, and tell the kiddies to live clean and respect the rules. Then I go to the Rotary and tell the business men: ‘Whether I win or lose my fight, I must be fit for my boy at night. I must come home to him day by day, clean as the morning I went away … Then I go to the wrestling arena and throw pepper in the eyes of my opponent.”

As his in-ring career wound down, Berry became a fixture as mouthpiece for the Fabulous Kangaroos, regarded as the greatest tag team of all time. Al Costello, founder of the Kangaroos, gave Berry his start as a manager in 1958 after flipping over a radio promo that he delivered for a card in Fort Worth, Texas. “Red made a lasting impression on my life, as a teacher and philosopher, and was a real source of inspiration to me during the three-and-a-half years we were together,” Costello told historian Scott Teal’s Whatever Happened to … ? in 1993.

For a time, Berry served as city commissioner for parks and recreation in Pittsburg, and a softball field there is named after him. After retirement, he stepped up his involvement with a host of civic and charitable organizations, and worked with youth groups through the Crawford County Sheriff’s Office. A serious stroke left him virtually unable to speak for about the last year-and-a-half of his life, though he still played golf and saw his friends around Pittsburg. Berry died of a heart attack at his home on July 21, 1973. His pallbearers included a who’s who of wrestling — Leroy McGuirk, Monsoon, Bob Orton Sr., and Orville Brown.

“I had the opportunity to call Red an inspiration to my wrestling and managerial career and while in Kansas City I had the opportunity of a lifetime to meet with him again, one on one,” said another Midwesterner, Percival A. Friend, who took Berry’s words and deeds to heart.

“Wherever lovers of the spoken word gather, Ralph ‘Wild Red’ Berry will never be forgotten. He was a pixie-like man who loved to talk and loved life. He loved people, and they, in turn, loved him back.”

— with files from Greg Oliver

2010 PRO WRESTLING HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES

Wild Red Berry

Edouard Carpentier

Stan Hansen

Mil Mascaras

Wahoo McDaniel

Danny McShain

Gorilla Monsoon

Kay Noble

Dusty Rhodes

Ben & Mike Sharpe

RELATED LINKS

Steve, Got a chance to see Red manage Monsoon live at the old MSG live in March 67′. It was great watching him as the voice of Bull Ortega,Tank Morgan and Hans Mortier.Red would even take bumps near the ropes dressed in his Bear Bryant Hat,houndstooth jacket and short cane.