Former UWF owner Herb Abrams didn’t stray from controversy. His public persona fed off of rumors. Whether those rumors were about him suing a 14-year-old for slander or not paying the talent, Abrams was a villain to sheet-readers and other industry insiders.

Those who only interacted with the bombastic, camera-craving public figure never got to see Abrams horsing around with his friends or acting like a goof to make others laugh. This part of Abrams’ story is a reminder that we shouldn’t be quick to judge an individual based off of first impressions, or public impressions. There’s more to a person.

As I was writing my book, Tortured Ambition: The Story of Herb Abrams and the UWF, I found myself seeking out the positives of Abrams’ personality. I found some, but I always wished that I could have uncovered more.

About a year after the book was published, I received a message from Scott Spielvogel. It turned out that he could have helped me immensely.

Spielvogel knew Herb Abrams’ other side. He was his best friend from high school up until Abrams’ death in 1996.

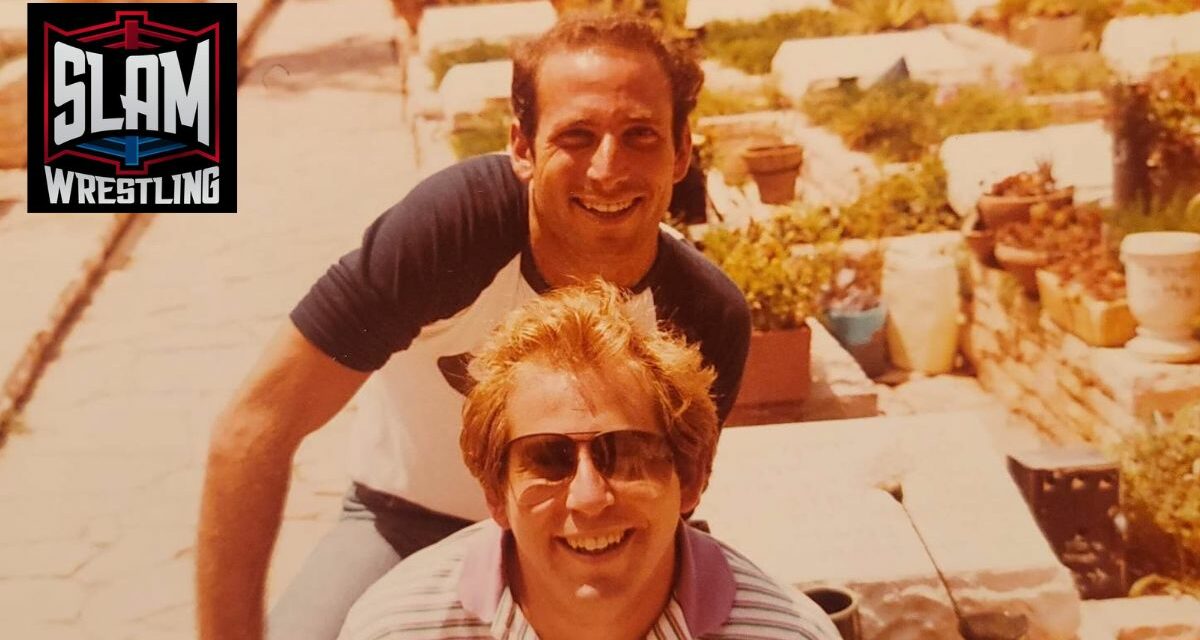

Herb Abrams and Scott Spielvogel in Israel. Photo courtesy Scott Spielvogel

In 1972, Spielvogel met Herb Abrams — who he called Herbie — while working at a clothing store in Fresh Meadows, Queens, New York. The 17-year-old Abrams introduced the 15-year-old Spielvogel to his energetic personality. It was a personality that shined when Abrams brought up girls or when he playfully cursed at his mom. Spielvogel had never met anyone like the future wrestling promoter before.

The two employees hit it off, but did go to different high schools — Abrams went to William Cullen Bryant High School in Astoria, New York, and Spielvogel went to Francis Lewis High School in Fresh Meadows. According to Spielvogel, Abrams “had that bold personality, and he always wanted an audience, and he always wanted to be the center of attention and joke around.”

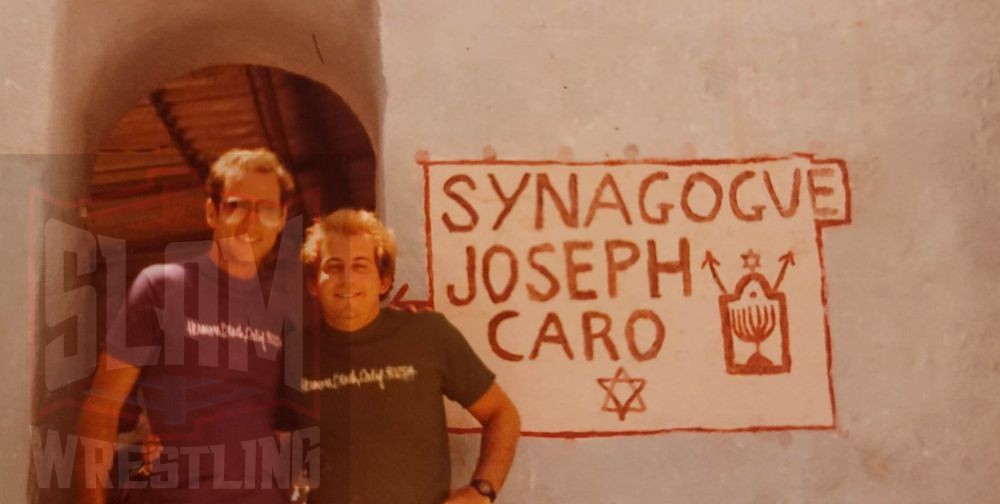

Herb Abrams and Scott Spielvogel in Israel. Photo courtesy Scott Spielvogel

By 1973, Abrams was driving Spielvogel around in his yellow Camaro, attempting to sneak into nightclubs with fake IDs.

Abrams had ambition. He was never content. He didn’t want to just work in a clothing store. He wanted to own the clothing store. In 1975, Abrams’ drive led him to co-own his first store, Lady Copperfield, in Flushing, Queens, New York, when he was only 21. He had big dreams. He wanted the shoe store to include other clothing.

His partner, whose identity remains unknown but he went by the name “Walter,” wouldn’t last long. A year after Abrams purchased the store, Walter was gone. Abrams’ explanation was that he bought Walter out. However, Spielvogel had questions.

“I’m like, ‘Really? Where did you get the money, and how much?’” Spielvogel recently told me. “There was never a fact that you could corroborate.”

Abrams took the little shoe store and expanded it, making Lady Copperfield a full-fledged boutique. Although it seemed like the business was good, it was hard for Spielvogel to know. Spielvogel thinks that the store’s demise began when Abrams stopped paying the manufacturers.

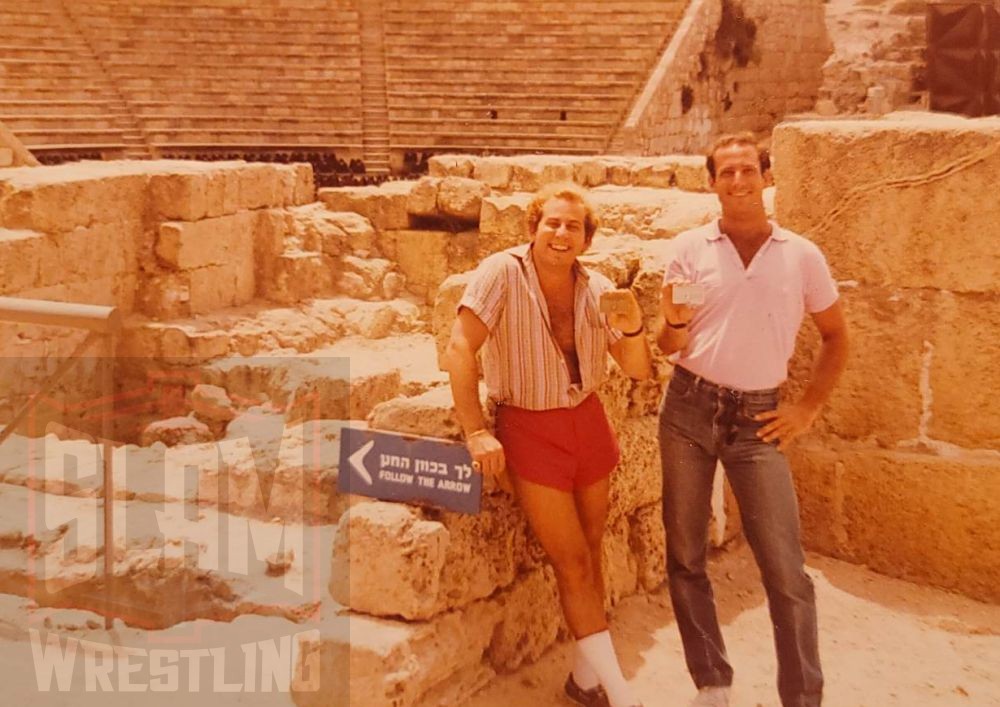

This seemed odd to Spielvogel, who knew Abrams to be generous with his wallet. How could the man who insisted on paying for dinner every night also not have enough money to pay the manufacturers?

Herb Abrams in Israel. Photo courtesy Scott Spielvogel

Abrams didn’t always rely solely on his store for income. Up the road from Lady Copperfield were two Italian men, whom Spielvogel describes as being “pretty much like a mobster type of guys,” that owned a grocery store. One of the men, who went by the name of “International,” would periodically go into deals with Abrams.

It wouldn’t last. One of those deals involved Abrams purchasing somewhere around $5,000 to $10,000 of liquor from one of International’s contacts. This was $10,000 in 1976, which would be over $50,000 in 2022. A meeting was scheduled.

“This guy came and he told Herbie, ‘All right, follow me in your car,’” Spielvogel explained. “They went to this apartment complex. The guy said, ‘All right, give me the money. I’m going to go in there and get it, and we’re going to load the back of your car.’ Herbie gave him all this cash. The guy went in the building and never came out.”

Spielvogel believes that the experience affected him greatly.

“I think that kind of set him like, ‘Wow, somebody screwed me. Maybe I could screw people too,’” Spielvogel said.

Lady Copperfield eventually closed. Abrams felt drained. He needed a new start, and California was it. At first, Abrams found a job at Lane Bryant, but Abrams couldn’t work for someone else. He needed to be in charge. So, in 1979, Abrams opened up a store in Manhattan Beach called Heaven Can’t Wait, which specialized in ladies clothing. Spielvogel later moved to California and began working for Abrams.

Although Abrams possessed a great mind for the clothing industry, wrestling was never far behind. While working at Lady Copperfield, Abrams occasionally invited wrestlers to the store for autograph signings. During these events, wrestling journalist Bill Apter would take photos for various publications. Abrams struck up a friendship with Apter. It was his first contact in wrestling.

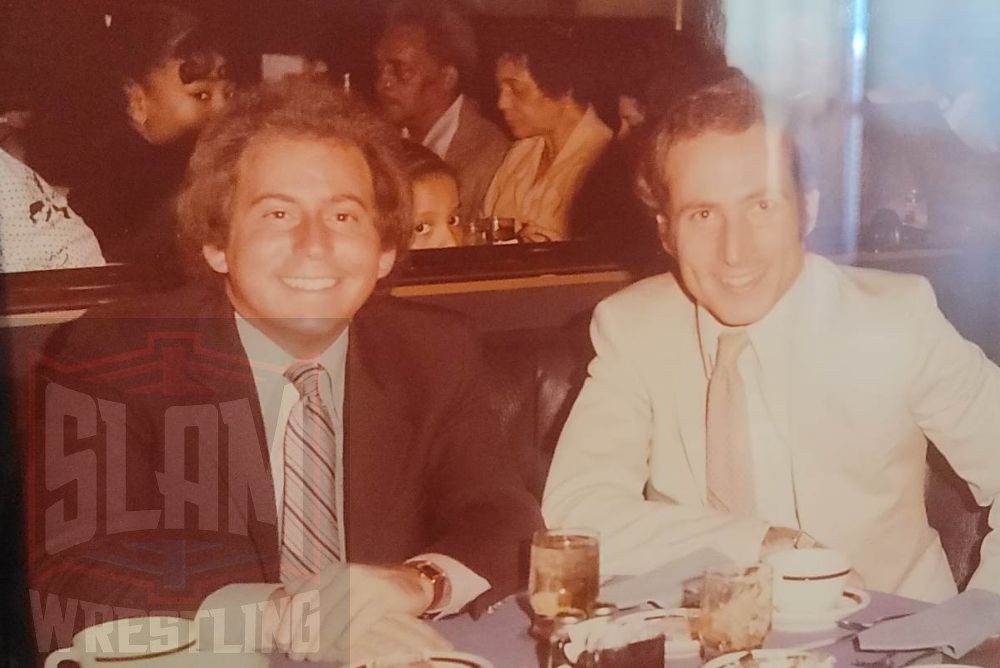

Herb Abrams and Scott Spielvogel out for dinner. Photo courtesy Scott Spielvogel

These were the origins of the Universal Wresting Federation.

One contact wasn’t enough to take on the world. Now in California, Abrams and Spielvogel began attending local wrestling shows. During one such event, they were placed near the entrance when Abrams spotted Chief Jay Strongbow in the backstage area. Abrams jumped the barricade and rushed over to Strongbow.

“One of the security people come running over to Herbie and he’s like, ‘No, no, I’m part of this,’” Spielvogel said. “All I could basically hear was Strongbow saying, ‘No, no he’s with me, he’s with me.’ And Herbie gets in the backstage and that’s where he meets [Paul] Orndorff. And that’s where he starts befriending all these people.”

It didn’t take long for Abrams to form relationships with many of wrestling’s biggest stars.

“He comes out and he is like, ‘Listen, I got Orndorff’s number.’ And he’s doing his normal routine where he’s talking about starting his own federation. He had this aspiration and all that. And that was really where it started,” Spielvogel said.

Abrams was always working.

“Orndorff comes into town. Herbie gets him picked up, but Herbie doesn’t just pick him up in a car, Herby uses a limo,” Spielvogel recalled. “He’s there to impress, to wine and dine because he needs them to think that he is this big promoter guy and he has to sell himself. So we go to lunch, we go to lunch on Los Seneca Boulevard. Then Orndorff asks if he can bring his friend Jesse Ventura.”

Jesse Ventura with Herb Abrams and Jeff Stienberger. Photo courtesy Scott Spielvogel

The lunch went well. Ventura became yet another acquaintance. Abrams was really doing it.

By 1985, Abrams had made a few contacts in the World Wrestling Federation. One of those contacts, a man whose identity remains a mystery (he can be seen in the picture below wearing a WrestleMania hat), got Abrams, Spielvogel, and one of Abrams’ friends, a lawyer named Jeff Steinberger, invited to the first WrestleMania.

An unknown WWF employee with Herb Abrams and Jeff Steinberger. Photo courtesy Scott Spielvogel

Even on the plane ride to WrestleMania, Abrams was interacting with one of the show’s key players, who just happened to be one of the biggest pop stars in the world.

“We get on the plane in LAX and who is sitting in first class? Cyndi Lauper,” Spielvogel said. “I couldn’t believe it. Herbie basically points his finger at her, just like these wrestlers doing the interviews. And he is like, ‘Lauper, we’re going to get you,’ and she starts screaming at him and it’s almost like a little wrestling duel going on in the plane. It was hysterical.”

Herb Abrams and Cyndi Lauper. Photo courtesy Scott Spielvogel

Upon landing, Abrams informed Spielvogel that they would be meeting Ventura, his wife, and “Mean” Gene Okerlund. Spielvogel and Abrams, who traveled everywhere in a limo, later picked up Orndorff and they rode to Madison Square Garden for the event. As if they weren’t starstruck enough, Abrams and Spielvogel bumped into Mr. T and Hulk Hogan in an elevator.

After WrestleMania concluded, and after Abrams and Spielvogel gave Big John Studd and the Iron Sheik a lift to the airport, they attended an after-party at Rockefeller Center where they met the likes of Bobby Heenan, Wendi Richter, Gorilla Monsoon and Andre the Giant.

The story doesn’t end at the party. On the following Monday, Abrams, thanks to the man in the WrestleMania hat, scheduled the famous meeting with Vince McMahon to talk about him becoming the promoter of the WWF on the West Coast. Only four men were there: McMahon, Abrams, Steinberger and Spielvogel.

“We get out to Connecticut and we go in and we’re in the reception area and all you hear on the speaker is Vince, ‘NBC is on line one.’ All the major networks are calling in,” Spielvogel remembered.

The unidentified man in the WrestleMania hat brought Abrams, Spielvogel and Steinberger to McMahon’s office then left the three of them alone. Twenty minutes later, McMahon walked in.

“The door opens up and there’s McMahon. And his first words are ‘Gentlemen, why are we here?’” Spielvogel recalled. “So, Herbie starts talking and he is not being totally coherent because he’s exhausted [from WrestleMania weekend]. And one thing about Herbie, and he’s the master of it, he never really prepared for anything. Everything was always off the cuff.”

McMahon looked confused as Abrams explained how the WWF should be promoted on the West Coast.

“McMahon is kind of looking at him, like, ‘Why do I need you?’ And Herbie really isn’t making too much sense at that point,” Spielvogel said. “So, Jeff Steinberger gets up and basically tells McMahon that you’re probably looking at wrestling’s biggest fan in history and what he’s done over the years to get to this point and to get to see you is probably something that nobody could have ever done.”

Five minutes later, McMahon had Abrams, Spielvogel, and Steinberger escorted out of the building.

“You got to give Herbie a lot of credit and kudos to get us that far,” Spielvogel said.

The Fabulous Moolah (Lillian Ellison) with Herb Abrams and Jeff Steinberger. Photo courtesy Scott Spielvogel

Much has been made about Abrams’ ability to attract top-billed talent to the UWF. Abrams maintained relationships with his contacts by pampering the wrestlers whenever they got into town.

“[Abrams] kept the relations going over the next number of years,” Spielvogel explained. “As these people would come into town, we always went to the sports arena and then we went to the hotel afterwards and we would go to the bar area and Herbie would do his thing [by charming the wrestlers with his charisma and by paying everyone’s tab].”

Spielvogel didn’t follow the UWF much, never went to a show. As Abrams became more preoccupated by wrestling, he and Spielvogel drifted apart. “I had little kids at that point, and I was working full time,” said Spielvogel. He stayed in the garment industry. “I was over it, I didn’t really need to get involved with the UWF.”

However, their friendship never ended and Spielvogel — who did not go to Abrams’ funeral in 1996 — still misses his pal.

“I think he was probably one of the most street-smart people I ever met, because he just knew how to judge people very well,” Spielvogel said. “He was also the best salesman.”

Spielvogel remembers Abrams not just because of what he accomplished, but because of who he was.

“Herbie was the sweetest guy in the world,” Spielvogel concluded. “He would do anything for anybody.”

RELATED LINKS

- Nov. 29, 2021: Herb Abrams bio as wild as you thought

- Oct. 11, 2021: Jonathan Plombon column – ‘Tortured Ambition’ describes my work on Herb Abrams book too

- May 6, 2020: Cookies, coke and cowboy boots aka the latest episode of Dark Side of the Ring

- Buy Tortured Ambition: The Story of Herb Abrams and the UWF on Amazon.com or Amazon.ca