A year ago, on February 6, 2022, a wrestler of many, many names died not long after her 83th birthday. The wrestling world hardly took note, though she, more than anyone else, was responsible for women being allowed to wrestle in New York State.

It’s time to learn a little more about Princess Chi-Chi … or Titi Paris … or Princess Ti Ti … or Chi-Chi Paris … Chickie Paris … or Chi Chi Empress of the Black Dagger … or Titi Djaileb … or any other number of variations.

A syndicated story that ran in many newspapers in late 1964 was based on a bout in England, where Djaileb spent roughly five years. On that occasion, she beat Anne Starr in Hawkhurst. The background at the time was a bill put forward by Cmdr. J.S. Kerans, the Conservative Member of Parliament for the Hartlepools, trying to ban women’s wrestling.

The bill lost, with Home Secretary Henry Brooke memorably saying in Parliament:

“This House sees nothing obscene in women’s wrestling. Carry on, women wrestlers. The House of Commons will not interfere with you.”

While it was a victory for women, the story still led off with a very dated quote: “Boy friends? I’ve got lots of them. But I guess I’m scared of marriage,” confessed Fathia Titi Djaileb.

The article did provide a lot of background on Djaileb, though some may have had a touch of ballyhoo.

- Her father, Bouhaik Djaileb served in the French army as a Spahi, which was the name given to the Algerian cavalrymen.

- Her mother wanted her to be a philosopher.

- Her family had all been taught to wrestle.

- She spoke five languages fluently.

- At 16, she toured much of Europe playing bongo-drums in a small band, and they hitchhiked for much of the touring.

- She started wrestling at age 17, mainly in circuses and fairgrounds in Algeria and France. “Men would challenge me. Most times I would beat them,” she said.

- Has a black belt, first dan, in karate, and has trained in kendo as well.

- Trained in boxing.

- Can hold four fully grown men on her shoulders at once.

Her ring gear at the time was described as:

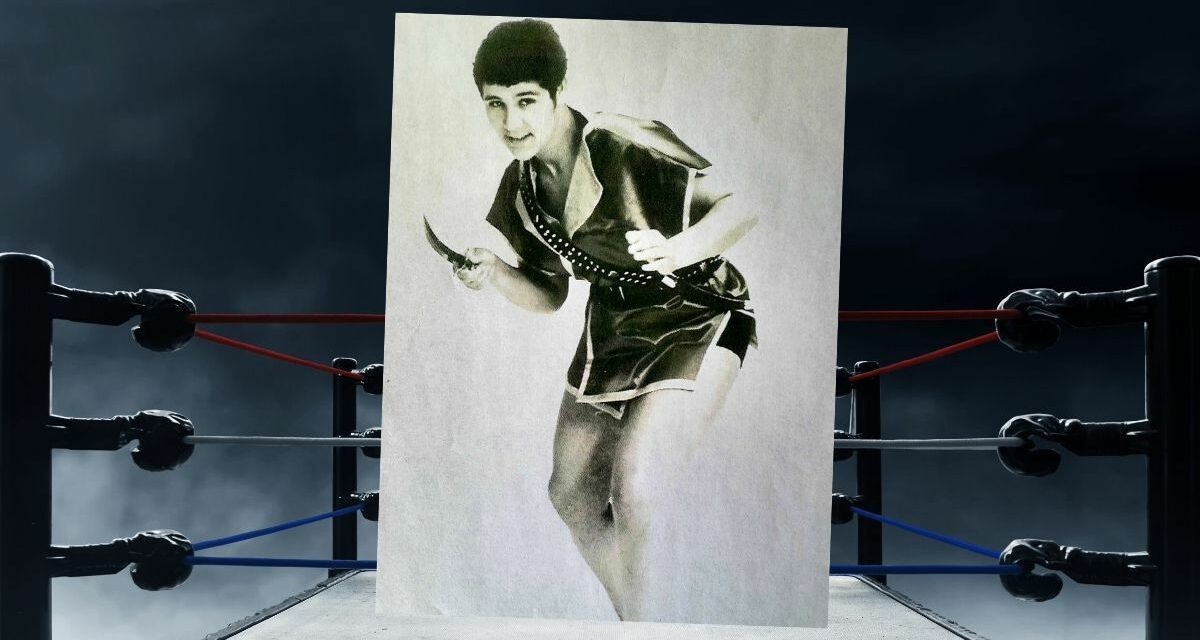

Titi wrestles under the title “Empress of the Black Dagger.” She enters the ring in a Roman helmet with crimson plume, Roman sandals, Roman armlets of brass and a Roman gladiator’s sword.

A glimpse at the gladiator outfit.

The Bristol, England, newspaper, Bristol Week End, had a piece about Starr and Djaileb in February 1964. “Titi wouldn’t think of giving up fighting. She loves it. She’s a tough, humorous pro who’s fought on the continent and takes an athlete’s pride in her body: she can lift 250 pounds, and isn’t afraid to handle the referee when she disputes his decisions,” the piece by Iain Gallantry reads. “An Algerian (her mother was one of her father’s five wives) she thrives on the mat-game. After dispatching Anne Starr at the Webbington she issued challenges to men, and chucked them all over the place. The well-fed voices of the clubbers roared delightedly when the Somerset boys were beaten by the muscular girl whose 38-inch chest swells to 42 inches when she takes a deep breath.”

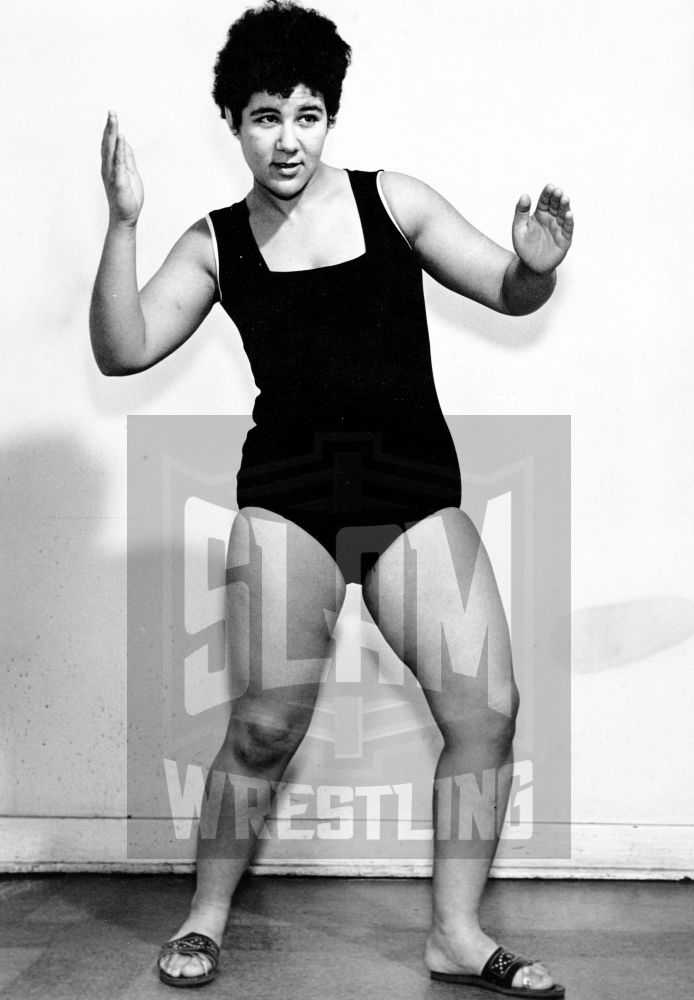

Naturally, looks come up in any article on women wrestlers in the 1960s.

From the syndicate piece: “Titi wears her dark curly hair cut short like a boy. Her eyes are long-lashed. ‘Sometimes I wear lipstick,’ she says. ‘My coloring is too dark to need other makeup.’ She does not smoke or drink. An Elvis Presley fan, she likes to twitch, rock-n-roll.”

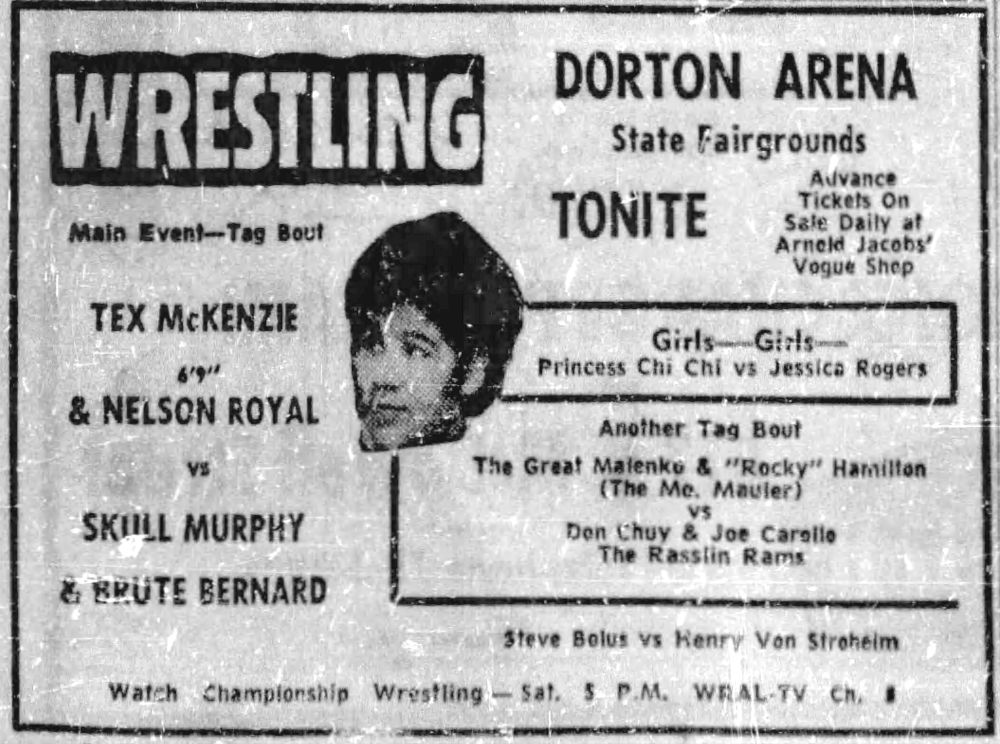

Raleigh, North Carolina, March 29, 1966

In a Columbus, SC, piece in March 1996, she is described: “Princess Chi-Chi, an Indian newcomer who is long on looks and mat ability.”

A September 1965 piece from Owensboro, Kentucky noted that Chi Chi Paris was “a worthy competitor from Paris, France, who has met and defeated most of the top women in Europe and this country.”

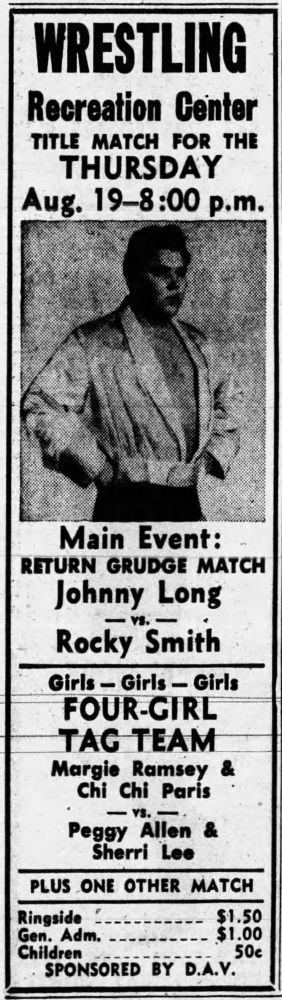

Johnson City, Tennessee, August 19, 1965

The line about boyfriends did, at least, have a conclusion in the article out of England: “Some day I would like to marry and have children. I might marry a wrestler. I don’t know. But I am like a sailor. I want to travel the world before I settle down.”

As for the real story, Fatiha Djaileb was born on January 27, 1939 in Algeria, to Bouhaik Djaileb and Zouleka Belal. There were many brothers and sisters. She met her husband Herbert “Jake” Jacobson, in New York City, and they lived in Southern California and Las Vegas, until Jake’s death in 2014. They had one child, Romy Tracy Jacobson, in 1971.

Her death on February 6, 2022, in Shelton, Washington, came after a long battle with dementia.

Chickie Paris. Courtesy Chris Swisher Collection

Her legacy rests in cracking open New York State for women’s wrestling.

On the defunct titiparis.com, she laid it all out there, repeated here:

During numerous jobs and various professional names, it was the efforts of Titi Paris in the 1970’s that changed New York State laws to allow legalized women’s wrestling. Lillian Ellison, professionally known as The Fabulous Moolah, is not the person responsible for changing New York laws to allow women wrestling, as she claims in her book, The Fabulous Moolah: First Goddess of the Squared Circle. Documentation is at the bottom of the respective pages.

November 30, 1971

I received confirmation from Edwin B. Dooley, Chairman of the State of New York Athletic Commission, that he received my letter dated November 24, 1971, in which I stated I was entitled to a wrestling license per the Title VII, Civil Rights Act, Section 703-A, Subd. 1 and 2. Mr Dooley agreed that the rules and regulations of the Athletic Commission prevented issuing a license at that time, but that there would be a study of the law.

On December 28, 1971

I received confirmation from Congressman Hugh L. Carey, New York, that he received my letter pursuing legalizing women’s wrestling. He reported he had no jurisdiction and suggested I contact State Assemblyman Melvin Miller.

On December 29, 1971

Congresswoman Bella Abzug acknowledged of my December 14, 1971, letter, but did not take action. She forwarded my letter to the National Organization of Women (NOW). She did mention the key words, “discrimination as a female wrestler.”

On January 11, 1972

Dee Atpert, representing NOW, sent me a copy of her reaction to my letter forwarded by Bella Abzug. She wrote she sent the letter to the State Athletic Commission of New York and wanted me to answer several questions. It is clear Atpert did not know that matches cannot be without a License, and that promoters can set up matches. I informed her that about 47 states allow women wrestling. Atpert proposed a publicity blitz if the Athletic Commission did not give in. She appeared to be very supportive of the cause.

Note: Apparently, NOW lost interest in the case because it would be too costly with no apparent gain for NOW.On February 8,1972

A letter, originally sent to Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm on December 8, 1971, was acknowledged by Assemblyman Vander L. Beatty as having been referred to him. He wrote that he would be sending a copy of the Bill.

On March 7, 1972

Mr. Beatty introduced a Bill (AB 11008), which was referred to the Committee on Government Operations. Mr. Beatty sent me a copy of the Bill with an accompanying letter dated April 13, 1972 in which he stated he had filed legislation to grant women wrestlers the right to practice their trade in New York. He expressed hope the Bill would be passed before the legislative session was completed. (Note: AB means Assembly Bill) At this point, the media got involved and there were articles in The New York Post (March 9, 1972, by Paul Zimmerman) and Wrestling Monthly (July, 1972). The first woman’s wrestling match in New York was March 8, 1972. Legislation still hadn’t passed at that time but an article by Jackson Pokress in Wrestling Magazine (mentioned to be dated July, 1972, in my marginal notes) clearly describes the match and mentions Princess Che Che (my wrestling name then) and the fact that WABC, WNBC, and WNEW all showed excerpts of the match Pokress encouraged the legislation of women’s wrestling.

June 6, 1972

The New York Daily News ran an article by Larry Fox recounting that State Athletic Commission Chairman Edwin Dooley made the announcement the Commission amended the rules to permit licensing of women wrestlers in New York. My name, or any of its variations, was not mentioned. I feel that the best-selling book by Roslyn Drexler was in large part thanks to my input to Drexler’s husband over several meetings in which I dictated my knowledge about my experiences in wrestling. Drexler was mentioned in Fox’s article.

July 4, 1972

Mildred Burke, representing the World Wide Women’s Wrestling Association, wrote a note on my behalf to Robert Anderson, Sports Editor of The New York Daily News, discussing the injustice done to ChiChi Paris (another of my wrestling names). Burke stated that ChiChi’s efforts alone got New York to legalize women’s wrestling. According to Burke, promoter Vince McMahon arranged to have Moolah “move in and reap the rewards.” Burke asked about bookings for me and disputed Moolah’s claims that 1.) She was as champion wrestler and 2.) She had defeated her (Burke) for the title of the World Champion. Burke accused McMahon of controlling a promotion/booking monopoly.

August 2, 1972

Edwin Dooley, Chairman of the NY State Athletic Commission, wrote me in response to my letter of July 28 (not included) mentioning his “chagrin because I think it was most unfair that you are denied the opportunity to wrestle in New York State”. He offered to write to Vincent McMahon and Moolah to help me. A copy of the letter from Dooley to McMahon stating, “Mrs. Titi Paris Jacobson who was instrumental in getting the bill passed to allow women to wrestle in New York State” asked for me to be granted opportunities to wrestle in New York. Dooley acknowledged that wrestling was “pretty much a closed operation,” but urged McMahon to include me in future matches.

August 4, 1972

I received a letter from General Counsel Robert M. Weitz, City of New York Commission on Human Rights, stating that Mayor Lindsay had forwarded my letter of July 26, 1972 (not included) regarding the complaint that I was unable to obtain bookings. Weitz said he had no jurisdiction because there was no sex discrimination and because the Athletic Commission was a State agency. He suggested I contact state authorities, specifically the chair of the athletic commission of Governor Rockefeller.

August 22, 1972

I received a note from Edwin Dooley stating my letter to Governor Rockefeller had been forwarded to him. He recalled his efforts on my behalf to ask promoter McMahon to help me, but said he had heard nothing. He enclosed a copy of the letter to Arnold Skaaland (no indication of who he was) asking for Skaaland’s intervention. He added that under New York laws, wrestling is an exhibition, not a contest, so state authority is limited. Matches are not promoted, but are regulated. The letter to Skaaland asked for help for me to get bookings.

September 19, 1972

Edwin Dooley wrote me again in response to my letter of September 1972 (not included) and acknowledged that Vince McMahon arranged for New York matches and said he would look into the matter for me.

September 21, 1972

I wrote Governor Rockefeller asking for his help in breaking the monopoly McMahon and Moolah controlled that prevented me from getting bookings. I said that Moolah only booked women she (or Vince McMahon) managed. I reminded him that my efforts were what legalized women’s wrestling in New York although over 20 years (amended in marginal notes to 40 years), many others had tried. I mentioned that Moolah could not represent or book herself as World Champion because New York only recognized matches as exhibitions (I enclosed a copy of the regulations). I pointed out that Moolah cannot be a promoter, manager, and a wrestler and that by issuing a license to Moolah, the athletic commission was breaking the regulations. I asked that Moolah not be allowed to wrestle in Shea Stadium on September 30, 1972.

September 23, 1972

I sent another note to Governor Rockefeller discussing Dooley’s note to me. I complained that New York residents who are wrestlers have trouble getting bookings, while out-of-state wrestlers do not, which is unfair. I wrote that it is also unfair that the athletic commission was bending the rules to help Moolah and the women she managed, trained, and booked. I said that Moolah was taking one-third of the earnings of the women she booked, plus the money for expenses and lodging. I again asked him to intercede and to stop Moolah from wrestling at Madison Square Garden on September 30th.

October 12, 1972

T. N. Hurd, Secretary to the governor of New York, wrote me in response to my letters to Governor Rockefeller. He claimed no violation had been found regarding managerial rules and that the athletic commission reported that Dooley had discussed my situation with McMahon who stated I would be given an opportunity to perform in the near future. I was advised by Hurd that the athletic commission suggested I get in touch with McMahon or Skaaland.

August 18, 1972

I wrote to the managing editor (no specific name) at The New York Daily News with my complaint about a July 3, 1972 article in which the paper stated that the first women’s wrestling match in New York was between Moolah and Vicki Williams. I told the managing editor about my match with Cora Combs on March 8, 1972, and the media coverage it garnered. I mentioned sending documentation by registered letter to Sports Editor Bob Anderson who claimed he never got them and wasn’t responsible for the write-up of July 3rd, written by Marsha Kramer. I wrote that Kramer admitted she didn’t know much about wrestling and wrote what she was told. I said I sent another registered letter to Kramer with paper documenting my claim, but that Kramer did not respond. I received no response and after finally reaching Bob Anderson, he refused to correct the write-up.

September 22, 1972

I wrote to Mr. Murtagh (no other identification) asking for help after sending him documents (unspecified). I complained about promoters only booking Moolah and the women she managed, promoted, and booked. I claimed that Dooley was controlled by the promoters and Moolah would not help me. I mentioned contacting Governor Rockefeller and asking him to stop Moolah from the September 30th match because of rule violations but that nothing has been done. I further complained that Moolah only was matched against the very women she herself managed and that I had been sidelined. I reminded Murtagh that I cannot earn my living in my own field and that I am not the only one facing this lockout. I summed up my problem by pointing out that the promoter, associates and the Athletic Commission itself are all part of the monopoly, either by control or tacit approval.

There is a piece about the whole legalization of women’s wrestling in New York State in Sisterhood of the Squared Circle: The History and Rise of Women’s Wrestling, by Pat Laprade and Dan Murphy. They wrote:

The bill officially went into effect on June 5, but Paris couldn’t wait that long. On March 8, less than 24 hours after the decision was made, Paris wrestled Cora Combs at Gil Clancy’s Telstar boxing gym, in what was the first women’s match in New York City since the sport was first banned.

As well, Titi Paris can be seen in the 1980 film about women’s wrestling, Below the Belt.

Titi Paris was honored by the Cauliflower Alley Club in 2000.

I think it was about 1970 when ChiChi moved into the apartment building where I lived with my parents and sister. I was 13/14 years old. She and my mother grew close, and I found her great fun to be around. She showed us photos of herself with Elvis Presley (she was hired as a bodyguard during a trip to NY), and pictures of her in the world of wrestling. She would often visit Brighton Beach in Brooklyn, at the rocks which divided bay 3 and bay 4, where a large group of friends gathered every year. It was like a family. We’d often visit even in the Autumn, making bonfires and roasting potatoes and corn on the cob.

I remember the day I came home and she was with my mother on the sofa. She was glowing and had a sweet smile on her face. My mother encouraged her to “tell me” and she said she was going to have a baby. I don’t recall if she and Herbie were married yet or not, but they were living together in her apartment, two floors down from ours. It was a one-bedroom, and they converted that bedroom into the baby’s room. What a sweet, pretty baby was Romy! Both ChiChi and Herbie were doting parents, and I only remember Romy into toddler age. After that, I guess everyone lost touch. I never saw the family again.

I have been living on Long Island since 1981, and never went back to Brooklyn, as the Brooklyn I remember from the “old days” is gone, but I recall our time there fondly, and I even remember our mutual address in Flatbush! I’d Google my friend once in awhile, and today, I found her obituary and this article. From the obituary, I was glad to read that she and Herbie had remained together although I was saddened to hear of his passing. I’m pleased to know that Romy got married, and I hope she is happy. It’s a shame that dementia made such an impact on ChiChi in her later life. I believe I shall make a charitable donation in her name. If I can find Romy, I’ll send her the receipt.

I send love to her friends and family members.

I send my gratitude to Greg Oliver for remembering my friend and writing this article.