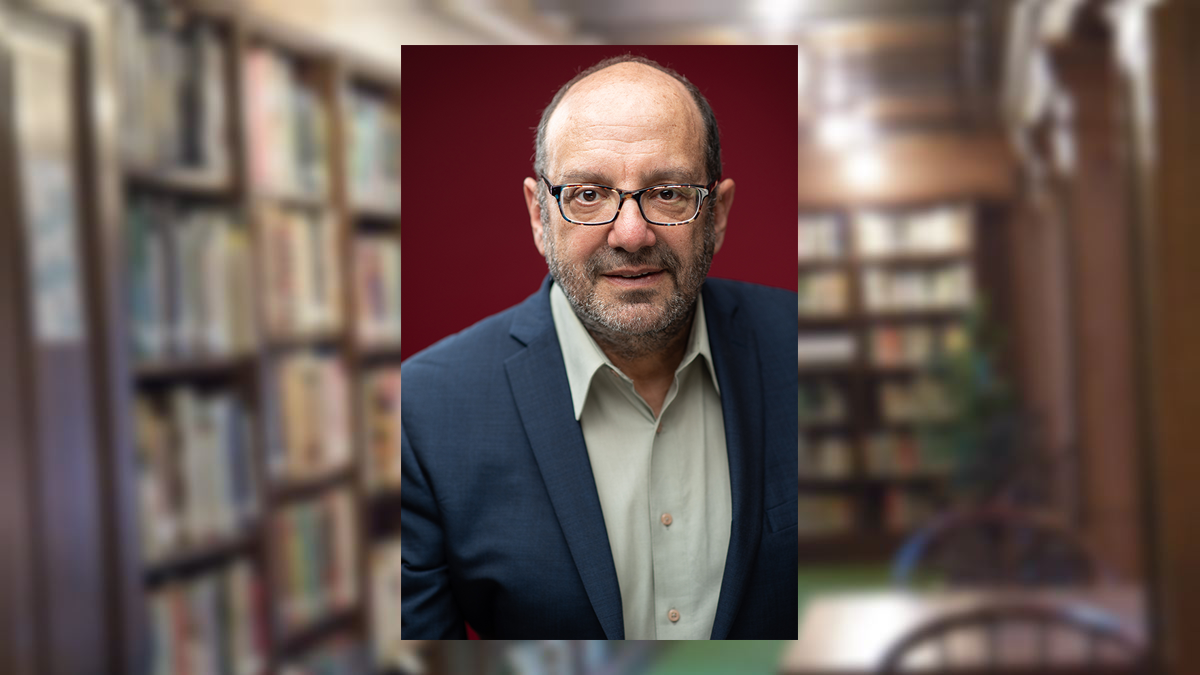

Irv Muchnick is no stranger to SlamWrestling.net. He’s contributed numerous pieces to the site, as well as co-authored the book Benoit: Wrestling with the Horror that Destroyed a Family and Crippled a Sport with the site’s co-founder Greg Oliver, Steve Johnson and Heath McCoy. Muchnick is a muckraker of the first order. Since the late 1980s he’s been shining a bright light into wrestling’s dark corners. He’s taken on murder investigations, steroid scandals, and unscrupulous legal and political maneuverings with an unyielding zeal.

His work is driven in part by a horror at the human toll paid by the men and women who work inside the wrestling ring, as well as a terrifying notion that the cynical and largely unchecked growth of World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) chairman Vince McMahon over the last four decades speaks to something rotten inside the American way of life that we ignore at our own peril. Muchnick once called McMahon “our cheerful guide to the dark side of the American soul.” Recent events in this country have done nothing to dissuade him of this fear.

We met for coffee and a doughnut on a very cold San Francisco morning.

Muchnick was born in 1954 in St. Louis, Missouri. His uncle was the legendary St. Louis wrestling promoter and founding member of the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA), Sam Muchnick. He can remember attending matches at the city’s Kiel Auditorium and spending time with former NWA world champions Gene Kiniski and Pat O’Connor, who would visit his uncle on occasion. “It’s my world,” Muchnick said, “so it’s sort of appropriate that I became obsessed with it.”

He attended Vanderbilt University on the school’s Grantland Rice scholarship for students with an interest in sports journalism. He left without graduating and moved to New York in 1979 to work as a literary agent, but found that he could make more money temping in law firms around Manhattan. Having long been an admirer of the darkly comic apocalyptic novels of Nathanael West, Muchnick relocated to a cabin in Margaretville, New York, a small village located three hours outside of the city, to try his hand at writing The Great American Novel.

He remained a fan of pro wrestling and would attend shows at Madison Square Garden on evenings when his uncle could arrange for seats at ringside. “I consider myself a soft-core fan throughout my whole life, though maybe I’m a closeted hard-core fan,” he said. Muchnick was also a regular viewer of Turner Broadcasting’s Saturday evening show, at 6:05 p.m., World Championship Wrestling (WCW), a now-legendary weekly broadcast of matches from the NWA promotion in Atlanta, Georgia. He was watching the evening of July 14, 1984, when a 38-year-old Vince McMahon, mannered and stiff in a gaudy yellow tartan jacket and matching vest, came on to announce that the time slot would now be filled with matches from his upstart World Wrestling Federation (WWF, now WWE). The change outraged longtime fans and was the most public sign to-date of the off-camera conflicts between McMahon and the more localized promoters who comprised the NWA. It became known as Black Saturday.

“I could see there was something going on,” said Muchnick. “There was a war behind the scenes because of cable creating a national marketing base, that this little mafia system that I’d grown up with was transforming into a clash of global brands. Like a lot of people with NWA roots, I was pulling for all these nincompoops who were fighting Vince McMahon, who had a vision and knew what he was doing and had money and had New York media connections and the Northeast population base behind him. That was an epiphany.”

Muchnick began looking more intensely at the small stakes grifting and manipulations that seemed to enable the dream world of pro wrestling to prosper. In addition to his other sports writing, which he’s published in Sports Illustrated, The New York Times Magazine, and San Francisco Weekly, he collaborated with writer Dan Bischoff on a wrestling feature that eventually ran without Muchnick’s byline in the Village Voice in 1985. In 1988, Penthouse published his article on the Von Erich family, “Born Again Bashing.” Spy magazine published “Pimping Iron,” his expose on McMahon’s then-nascent World Bodybuilding Foundation, in 1991. Muchnick also secured a book deal to write on the pro wrestling wars, that eventually fell through. (Muchnick was a contemporary of writer Ray Tennenbaum, whose unpublished book on the wrestling wars, Sleeperhold, Slam covered here.)

“In America violence is idiomatic,” Nathanael West once wrote and for Muchnick, the country conformed to the same grim contours. You could see its shadow in the slipshod investigation into the death of Nancy Argentino, girlfriend of World Wrestling Federation(WWF, now WWE) star Jimmy Snuka, or in the way state athletic commissions were so willing to turn a less-than-discerning eye to overseeing the health of wrestlers.

Muchnick left freelance writing to work for the National Writers Union and then as a litigation consultant, working to protect the rights of freelance writers to their work. His work in those roles led to the United States Supreme Court case, Reed Elsevier, Inc. v. Muchnick. He settled into domestic life before returning to writing in 2007 with Wrestling Babylon: Piledriving Tales of Drugs, Sex, Death, and Scandal, a collection of his work from the 1990s published by ECW Press. Muchnick had intended then to stop covering wrestling, but while boarding a plane to return from a stop on that book’s promotional tour, he heard the news breaking out of Fayetteville, Georgia about the deaths of wrestler Chris Benoit, his wife Nancy, and their seven-year-old son Daniel.

Over the course of three days in June of 2007, Benoit, a star in McMahon’s WWE, murdered his wife and child before taking his own life. The WWE aired a three-hour tribute to Benoit, though news leaked out during the show that Benoit himself was the lead suspect in the crime. The company then proceeded to prevaricate, dodge, and offer misdirections as the truth unfolded.

The horrific story of the Benoit family sent professional wrestling careening through the looking glass. Grisly coincidences accumulated around the case. Biff Wellington, a former tag team partner of Benoit in Stampede Wrestling, was found dead in his apartment by his parents just before the weekend that the Benoit murders unfolded. In Stamford, Connecticut, the location of the corporate headquarters of the WWE, a then-anonymous wrestling fan edited Benoit’s Wikipedia page to include a reference to the death of Nancy Benoit, 14 hours before Georgia authorities discovered her body. Who knew what, and when, was very much an open question. Muchnick dove into the case, first on the aforementioned quickie book, Benoit: Wrestling with the Horror that Destroyed a Family and Crippled a Sport, published within four months of the double-murder suicide. Muchnick went deeper still, with 2009’s Chris & Nancy: The True Story of the Benoit Murder-Suicide and Pro Wrestling’s Cocktail of Death. The book was updated and reissued as an eBook in 2020, and is now once-again available in hard copy. The book examines the Benoit case in harrowing detail, and is as complete of a record as is likely to ever be produced.

Muchnick dove into the case, first on the aforementioned quickie book, Benoit: Wrestling with the Horror that Destroyed a Family and Crippled a Sport, published within four months of the double-murder suicide. Muchnick went deeper still, with 2009’s Chris & Nancy: The True Story of the Benoit Murder-Suicide and Pro Wrestling’s Cocktail of Death. The book was updated and reissued as an eBook in 2020, and is now once-again available in hard copy. The book examines the Benoit case in harrowing detail, and is as complete of a record as is likely to ever be produced.

For Muchnick, the 2007 murders were a harbinger of what he calls “the wrestlingization of America on an apocalyptic scale.” It’s a broad phrase meant to get at the way the incredulity that has been the defining characteristic of wrestling fandom since at least the 1920s has taken hold in all aspects of American life. “In America,” Muchnick wrote in the book’s updated foreword, “life is defined by making money. Corporations and their soulless stewards enjoy an uncanny knack for compartmentalizing everything, even double murder-suicide. They deny, they spin, they manipulate, they run out the clock — whatever it takes to keep the masses mesmerized and their eyes off the ball of measures that would hold secondary forces accountable and make repetitions of our worst history less inevitable.”

“All these wrestling people, they buy their own gimmick,” he said. “It’s so psychologically interesting. It’s like we don’t think they’re real people, but they are, and they kind of inculcate those values and that ethos in all of us watching. It’s very mesmerizing.”

Muchnick’s writing will never be described as laconic, but neither will it ever be called half-hearted. The dirty business of empire building, personified in many ways by McMahon’s ascent from the rundown and neglected trailer parks of Pinehurst, North Carolina, to the tony estate of Stamford, both fascinates and horrifies him. “We all underestimated him,” said Muchnick. “The joke is on us. He understands something about the serious frivolousness of our world that we don’t want to bring to the surface. And he’s a brilliant businessman, there’s no getting around it. He’s a clown, too, but he won the war, and he won the war for a reason.”

Muchnick’s research on the Benoit family led him to a more serious interest in chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the degenerative brain condition associated with repeated head traumas. It’s most commonly found in football, hockey, and boxing, but is a risk to athletes in almost all sports. CTE was widely discussed as a factor in the Benoit murders. Muchnick feels that he may have underplayed it in his original research on the case, and has increased his focus on it in subsequent editions.

He’s also devoted extensive resources to researching sexual abuse in youth sports, focusing particularly on swimming. “My perspective on wrestling and football and 14-year old girls being raped by their coaches because their parents think they can get college scholarships and Olympic slots is a public health perspective,” he said. “We have this weird, mass entertainment, spectacle-way of doing things in this country at this point in time. It’s very bread and circuses. The joke I make is that The New Yorker and The New York Times won a Pulitzer for covering Harvey Weinstein, but they don’t give out an un-Pulitzer for the 30 years they stuffed the story. That’s my role in the media food chain. I’ve realized that I’m low on it, but there’s stuff down there that’s off and wrong, and there’s stuff down there that’s true that just hasn’t worked its way up the so-called credibility system yet. And I try to write with great documentation and credibility, but I don’t hold anything back.”

Muchnick currently lives in Berkeley, California, where he keeps tabs on his three grown children, a fourth in high school, and a grandchild. He publishes extensively both at his website, as well as in major media outlets. His work investigating former Irish Olympic swimming coach George Gibney, who now resides in the United States and is the subject of an extradition campaign by the Irish government, has appeared in The Colorado Springs Gazette and Salon. He jokingly calls pro wrestling the black hole of his career and sees this reissue of Chris & Nancy as his final word on it. When pressed, though, he admits that, given the right circumstances, he could return. “Who’s to say that the next thing that happens won’t be even more wrestilng-ish, and that I won’t step in and write about it?” he admitted.

That grim admission that some next tragedy is forever looming is a haunting reminder of just how little change has taken place in wrestling, and just how tenuous the changes that have occurred will likely prove to be.

“I’ve been sued and threatened with lawsuits on several occasions and I’ve gotten past it,” Muchnick said. “I reached a certain stage of my life and career where I just said, ‘I’m going to let it all hang out.’ And I do, and I think that when you have that attitude, what I would say is that you’re inoculated to some extent. People say, ‘Well, The New York Times isn’t publishing that but you are,’ and I’ll say, ‘That’s the point.’ I’m worried if it’s wrong but otherwise it’s just me and my legacy as a writer, now. People think I’m a crazy person and I’m just a person saying what I want to say.”

RELATED LINKS