Few wrestling companies have enjoyed as widespread critical acclaim as Shohei ‘Giant’ Baba’s All Japan Pro-Wrestling (AJPW). And few wrestlers have as much experience in that company as Richard Slinger. From 1992 to 2000, Slinger (real name Richard Aslinger, 49) wrestled against and teamed with some of the biggest legends the sport of professional wrestling has ever seen. And although he retired in 2005 after a tour with AJPW splinter promotion Pro Wrestling NOAH, Slinger has retained a vast wealth of knowledge of the iconic King’s Road promotion and the various legends it has spawned.

“With King’s Road, you’re painting a portrait,” Slinger told SLAM! Wrestling in the fall of 2020. “It’s the only style of pro wrestling I know. It’s all about being snug, believable, and credible. That era was one of a kind. I don’t think it can ever be recreated.”

Trained by his uncle Terry ‘Bam Bam’ Gordy, Slinger entered professional wrestling as a very young man. But he didn’t want to become a character or a larger-than-life personality. He was inspired by the realism and sport-like legitimacy that could only be found in Japan.

“I wanted to wrestle in AJPW after hearing some of the stories from my uncle and watching videos of the UWF. It was a shoot-style wrestling that didn’t run the ropes and had a lot of submissions and kicks. It was so fun to watch, I knew I wanted to do it like that. I really studied those VHS tapes and was impressed by people like (Akira) Maeda, the original Tiger Mask (Satoru Sayama) and (Nobuhiko) Takada. I quit high school wrestling and started Tae Kwon Do at the local YMCA. I fell in love with it. I started wrestling under a hood as The Karate Kid because I was still in high school. After graduating at 17, I was off to train in Tokyo less than two weeks later.”

But it wasn’t just the presentation of Japanese puroresu that impressed Slinger. He appreciated the lengths to which the wrestlers and promoters went to protect the business and the legitimacy of their craft. It wasn’t uncommon for the trainees in AJPW’s dojo to cover up all the building’s windows with newspapers to keep peering outsiders from learning what secrets lay within. And, as Slinger learned firsthand, the first lesson an AJPW rookie learn was how to protect the sport at all costs.

“The Great Kabuki told me that all of us [the AJPW trainees] would get taught how to shoot before we’d take our first bump. That’s because kickboxers and other professionals kept coming up to challenge the wrestlers because they thought wrestling is/was fake. The veterans taught us how to shoot so that if those people ever tested us, we could prove them wrong.”

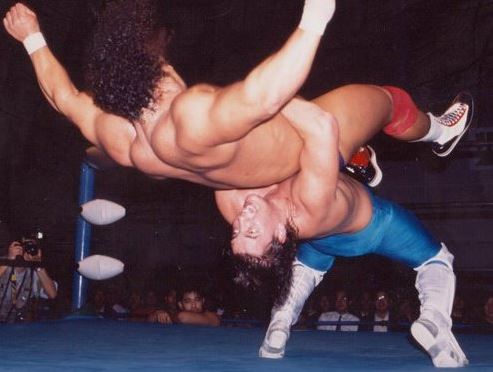

Richard Slinger lands a German suplex. Image courtesy of Slinger’s personal Facebook page.

Slinger was in AJPW during what became its golden age. After Genichiro Tenryu left the company, promoter Giant Baba decided on elevating a quartet of wrestlers up to the main-event level. That quartet was composed of Akira Taue, Kenta Kobashi, Toshiaki Kawada and Mitsuharu Misawa. Together they became known as the Four Pillars of Heaven, and Slinger wrestled against all of them. And throughout the decade, he witnessed firsthand how popular and skilled AJPW’s roster was. Part of that was the pure talent possessed by the wrestlers themselves, and part of it was from the intense training they underwent. And another big part came to the creative skills of AJPW’s founder and promoter, Shohei Baba.

“I know that (Giant) Baba was a genius when it comes to promotion. He took care of the boys, even the gaijins. Every time we sold out Korakuen Hall or Budokan, he would give us a bonus. Every time we arrived in a city, I would hear a speaker from a car shouting out the names of the stars going street to street. It was him who pushed the angle for the rivalry between Misawa and [Jumbo] Tsuruta after Tenryu left, thus setting the start of big money and big business. He was such a great and respected promoter. I never signed a contract with All Japan or NOAH. Our business was by word of mouth only.”

Richard Slinger gets ready for a match. Image courtesy of Pro Wrestling NOAH

Slinger also divulged just how generous his peers and bosses were while in Japan. As a rookie, then-AJPW veteran Genichiro Tenryu paid for his ring gear. When he got injured early on in a tour for NOAH, Misawa paid him the full amount of the tour’s pay, even though he had to leave early due to injury. And if a venue sold out, all the wrestlers would get bonuses.

And considering how many times AJPW and NOAH sold out those buildings, those bonuses would have been plentiful. AJPW, with Misawa main-eventing, sold out the famous Budokan Hall (the Japanese equivalent of Madison Square Garden) 53 times during his prime, and from June 8, 1990 to early 1996, sold out all of its subsequent 200 shows. The closest equivalent record in North America is Bruno Sammartino’s record of 45 Madison Square Garden sellouts.

And NOAH sold out the famous Tokyo Dome twice in the early 2000s, getting well over 55,000 fans for each show. Bear in mind this was during a period when pro wrestling was waning in popularity in Japan and mixed-martial arts was taking the country by storm.

Slinger witnessed firsthand just how crazy the fans got during those years. While he’d be lower on the card, the fans would go crazy for the main event matches, especially if they featured Tenryu, Misawa or Kobashi. He went on about how they’d make so much noise that it completely obliterated the stereotype of the silent Japanese audience watching studiously.

“Some of Tenryu’s matches were in Hokkaido, and there were no chairs in those venues. The fans had to sit down on the floor, and the fans didn’t mind, and they still found ways to make noise. In the bigger buildings across the country, the fans would sit in chairs and stomp their feet. The buildings would shake to the point that it felt like an earthquake.”

As a wrestler, Slinger had the pleasure of competing against some of the toughest, stiffest wrestlers of all time. On one occasion, he received a stiff kick right in the eye from Toshiaki Kawada. But instead of calling off the match, they continued, with Slinger hitting back just as hard not long afterwards. “If you don’t give them a receipt, they’ll send you home. If they stiff you, they expect a receipt.”

That deep-rooted mental toughness, in Slinger’s opinion, is based on Furinkazan, a phrase from Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, which states that one must be “as swift as wind, as gentle as forest, as fierce as fire, as unshakable as mountain.”

And when it was applied to the matches, it led to some of the greatest pro wrestling matches of all time. The AJPW matches of the 1990s were hot commodities on the tape trading circuit in North America, and that style has been emulated many times in later years by wrestlers around the world. And while most people look to that style and focus on the dangerous head spikes and high-angle suplexes, the real key feature was the sense of legitimacy the matches gave off. AJPW blended realism into matches more than any other promotion in its day. When a wrestler took a big move, it wasn’t uncommon for the referee to slap them loudly to sell the idea that they’re legitimately knocked out and the fans truly believed it. This, combined with deep and emotional storytelling, complicated story narratives that extend over years, and realistic selling, made King’s Road All Japan such a successful company.

Slinger provided a personal experience of this philosophy in action, in a match against AJPW legend Kenta Kobashi.

“[Kobashi] caught one of my kicks and hit the Burning Lariat. He landed it so hard it busted my lip and I needed stitches. I was out. Then I felt something tugging on me. It was Kobashi, and he wanted to hit it again because he didn’t think it looked good. That left the fans asking themselves, ‘Was it a work? Was it a shoot?’”

Slinger left AJPW in early 2000 to focus on himself, before joining Misawa’s new company, Pro Wrestling NOAH, shortly after it formed. While back in the United States, he started a bail bond business and became involved with the Armed Forces. He became a member of the Army Reserves and has since served as an honor guard, attending funerals of fallen American war heroes and firing the 21-gun salutes for them as well. And while he has always enjoyed military-type drills and technical military training, Slinger has also attributed his success in these fields to his training with AJPW when he was a rookie.

“The biggest accomplishment of my life was going through the training at the All Japan dojo. I arrived two weeks after I graduated at age 17. I even saw a Japanese boy come from far away by train. After about 30 minutes of training his words were ‘dikimasen,’ which means ‘I can’t do it.’ He then had to make that long trek back home. When I went through basic training at the air force at the age of 27, I was outdoing those that were 18. The mindset I learned in Japan has helped me in every aspect of life.”

Though his in-ring career has long since ended, Slinger has many fond memories of his time in Japan. He has wrestled a veritable who’s who of puroresu, from the original Four Pillars, to Jun Akiyama, to the top guys in the early years of NOAH. He also enjoyed teaming with top gaijin wrestlers like Gary Albright, Big Van Vader, and “Dr. Death” Steve Williams (whom Slinger noted even Kurt Angle praised for his wrestling skills).

Although he never achieved any championship glory, that didn’t bother Slinger. He saw wrestling as a business, and he was there to do what was asked of him. He took pinfalls more often than not, but did score some wins over rising stars in NOAH such as KENTA and Naomichi Marufuji. And just as he had in the 1990s with the original Four Pillars, he wrestled and helped elevate a new generation of wrestling stars.

“They knew I was a businessman, it didn’t bother me to not have titles. Doing business and doing my job was enough for me. Entertaining the people and knowing that I’m helping business was enough me. Misawa took care of me and I’d take care of business.”

RELATED LINK

Great article! Slinger is someone I always saw in results listings, but never really knew anything about. Now I have to go watch a bunch of his matches.

He seems like a really well-read and thoughtful guy. Would love to hear even more about his AJPW experiences.