Koji Miyamoto fell in love with pro wrestling as a 10-year old living in Mito City and his deep love for the sport and its participants has never waned. His fiftieth anniversary as a fan will be particularly meaningful for him. In July, he’ll travel to Waterloo, Iowa to receive the Melby Award at the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. The Melby award, named for late historian James C. Melby, recognizes excellence in professional wrestling writing or historical preservation.

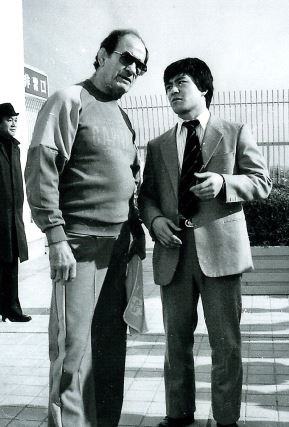

Lou Thesz and Koji Miyamoto in 1979.

There is no doubt about the importance of Miyamoto’s many contributions to the preservation of wrestling’s history. Through his work as a translator and manager for American wrestlers working in Japan, he became close friends with several wrestling legends and earned the trust of many others. And for over 30 years he has worked to spread information on the history of Japanese wrestling to fellow fans in Japan, as well as historians around the world.

Televised wrestling was in no short supply in Japan in the late 1960s. It had already been a regular feature in Miyamoto’s house thanks to his father and brother, but it wasn’t until he first saw Lou Thesz in 1968 that it finally captured his attention and imagination. Known as Tetsujin, the Iron Man, Thesz was already a well-respected figure in Japan, famous for his matches in the late 1950s with Rikidozan, the forefather of Japanese wrestling. Thesz’s athleticism and no-frills, physical style appealed to Miyamoto instantly.

“What Lou showed me was true professional wrestling. I don’t want to see professional wrestling as showbiz,” Miyamoto tells me over the phone in excellent English from Mito City, where he continues to live. “I want to see pro wrestling as a sport. Even when I was 10, I wanted to believe in that true wrestling technique and wrestling as sport.”

Later that year, Mito City’s Channel 12 began broadcasting films of classic wrestling from Chicago promoter Fred Kohler and Buffalo promoter Pedro Martinez. The films were brought to Japan through a connection with Atlanta promoters Ray and Ann Gunkel and through them, Miyamoto was exposed to wrestlers like Verne Gagne and Antonino Rocca. He developed a deep affection for the black and white stars. The broadcast only lasted until 1972, but Koji was fortunate, for a brief period, to be able to enjoy classic American wrestling and contemporary Japanese wrestling simultaneously.

Wrestling was enjoying an incredible boom in popularity across Japan during this era. There were television broadcasts of wrestling every evening and a daily newspaper, Tokyo Sports, allocated several pages to wrestling coverage. “It was like a TV Guide for wrestling, everyday,” he remembers. And while live wrestling shows only came to Mito City a handful of times each year, Miyamoto was able to occasionally make the two-hour trip to Tokyo to see live wrestling on a more frequent basis. In 1974, he met Thesz for the first time and got an autograph that he still holds onto.

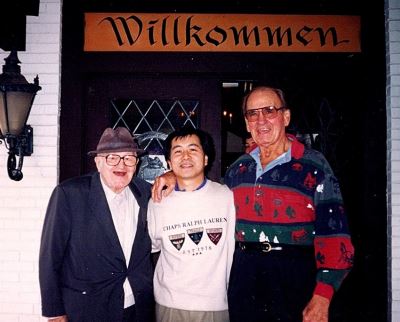

Sam Muchnick, Koji Miyamoto and Lou Thesz in August 1995.

In 1976 he moved to Tokyo to attend university. There, he was able to attend matches from Antonio Inoki’s New Japan, Shohei Baba’s All Japan, and Isao Yoshihara’s International Wrestling Enterprise (IWE). Unlike Baba and Inoki’s promotions, Koji remembers IWE’s offices as being accessible to fans. In 1977, he worked up the nerve to approach them about becoming the interpreter for Thesz and other American wrestlers travelling to Japan. Incredibly, they agreed.

He became fast friends with Thesz, and through that relationship he gained the trust of the other American wrestlers, including Dick the Bruiser, Verne Gagne, and Gypsy Joe. “[Koji] and Lou were almost always on the same page and had so much of what Lou called ‘mutual respect,'” emailed Thesz’s widow, Charlie Thesz. “Koji was instrumental in assisting many wrestlers in Japan.”

“I kept kayfabe cold, everytime,” Miyamoto says. “I was protecting Lou. That was my business and I never exposed secrets to TV, to the newspapers, to the magazines. I protected it, always. Maybe for today’s fans it’s ridiculous, but I had to protect the wrestling business on behalf of every older generation guy … I was serious.”

Nick Bockwinkel, Lou Thesz, Koji Miyamoto, and Billy Robinson in May 1992.

Despite a full-time job, Miyamoto travelled with a number of wrestlers and began contributing to Japanese wrestling magazines under the pen-name Tomomi Nagare.

IWE closed in 1981, slowing down Miyamoto’s travel schedule. “I am still treasuring my five years with IWE gaijins,” he says. He stayed close to Thesz, however, and began acting as Thesz’s manager for his frequent trips to Japan to work with different promotions. Over time, the two developed an incredibly tight bond.

Lou and Charlie Thesz traveled to Japan for Miyamoto’s wedding in 1986 and in the early 1990s, he helped arrange for Thesz’s autobiography, Hooker, to be published in Japan. “The manuscript was translated in kanji and the result was exactly the sort of product we’d originally hoped to see in the United States: a hardback with lots of photos,” wrote Thesz’s co-author, Kit Bauman, in his foreword to the re-issued version of Hooker published by Crowbar Press.

Jim Melby, Janet and Kinji Shibuya, and Koji Miyamoto in June 1997.

In 1995, Miyamoto relocated to the United States when he was assigned to his company’s office in San Francisco. It was while living in the Bay Area that he became close to wrestlers Kinji Shibuya and Pepper Gomez. It was also while living in California that he was able to meet in-person several of the people he had first met through the pen pal section of Wrestling Revue magazine. Beginning when he was still just a teenager, Miyamoto frequently exchanged newspaper clippings, magazine articles, and programs with Jim Melby, Don Luce, J Michael Kenyon, Fred Hornby, and Tom Burke. As video recording became more accessible, he began sending tapes of Japanese wrestling, as well, providing much of the footage exchanged among tape traders in the late 1980s.

It was this loose group of pen pals that would later form the core of wrestling historians in America. “There was no word of historian back then,” Miyamoto says. “We were just big fans. The word historian, I would say, came in the past 20, 25 years.”

Living closer to his friends than ever before, he worked to organize the informal network into a more cohesive unit. Miyamoto pulled in other significant researchers like Haruo Yamaguchi, Chuck Thornton, Steve Yohe, and Scott Teal, and dubbed the group The International Wrestling Historians Club. Together, they’re responsible for producing the vast amount of research on wrestling’s past to emerge in the last 30 years.

“For 25 years Koji has been my best friend in wrestling,” wrote Yohe over email. “It was my friendship with Koji that got me accepted by major historians. He has been a major part of every project I’ve ever worked on.”

Koji Miyamoto with Devil Murasaki (Akio Murasaki).

Miyamoto returned to Japan in 1998, and continued to work with Thesz until the champ’s death in 2002. Charlie Thesz gave several pieces of his ring gear to Miyamoto as a reminder of their relationship. “Lou Thesz was my American father,” Miyamoto says. “I still feel like that.”

In recent years, Miyamoto has stayed busy. In 2011, he returned to America to interview Stan Hansen and Barbara Goodish, widow of Bruiser Brody, for a DVD celebrating Hansen and Brody’s career in Japan. As part of fan festivals in Japan, he has conducted live interviews with The Destroyer (Dick Beyer), Tatsumi Fujinami, Bob Backlund, and Keiko Momota, widow of Rikidozan. He is one of the best-respected wrestling historians in Japan, and has written more than a dozen books on wrestling history.

He’ll be in attendance at the induction ceremonies — the 20th anniversary — July 26-28, 2018, at the the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame, based in the National Wrestling Hall of Fame Dan Gable Museum in Waterloo, Iowa. This year’s inductees are Dan Severn and Owen Hart; the Lou Thesz World Heavyweight Championship Award will be presented to Booker T Huffman; the Frank Gotch Award will be presented posthumously to “Bruiser Brody” Frank Goodish, represented by his widow Barbara; The George Tragos Award, which recognizes an amateur wrestler excelling in mixed martial arts, goes to Ben Askren.

Even speaking with Miyamoto now, his enthusiasm and affection for the larger than life figures that first caught his eye on Fred Kohler’s old black and white films still feels close to the surface. Through his respect for their business and for his unending efforts to preserve their work and memory, he has more than earned his spot in the National Wrestling Hall of Fame.

TRAGOS/THESZ CLASS OF 2018 STORIES

- July 30, 2018: Hall of Fame honours Booker T, Severn, Hart, Brody and others

- July 28, 2018: Honours keep coming for Dan Severn

- July 21, 2018: Five questions with WWE producer Adam Pearce

- July 9, 2018: Melby Award honours Koji Miyamoto’s many contributions

- Mar. 26, 2018: 2018 Tragos/Thesz HOF Class announced

RELATED LINKS