The Cauliflower Alley Club’s prestigious Iron Mike Mazurki Award will be presented to Steve “Sting” Borden at the organization’s 58th annual gathering later this week.

The Iron Mike Award is given not just for accomplishments in the ring, but for overall contributions to the wrestling community. It’s the club’s top honor, and arguably the top award in pro wrestling, with winners voted on by a community of peers. Past honorees form a highly exclusive club, including mat greats Lou Thesz, Mark Henry, Steve Austin, Trish Stratus, and Walter “Killer” Kowalski. It’s a group that Sting undeniably belongs in.

In professional wrestling, a connection with fans can’t be faked or manufactured. And if there was one thing that set Sting apart from his contemporaries, it was his ability to genuinely connect. It’s been said before but bears repeating; there were wrestlers who were bigger than he was, who were faster than he was, and who were better on the mic, but few were as solid in all those categories while being so good for so long at building a bond with audiences.

Born on March 20, 1959, in Venice Beach, California, Steve Borden was a local bodybuilder who had no idea what pro wrestling even was, when he was approached by a group of trainers, including the famed former wrestler Red Bastien, looking to form a quartet of muscleheads in the mold of the Road Warriors. An evening of matches at the Los Angeles Sports Arena sold Borden on a life pursuing wrestling fame; “As soon as I heard the roar of the crowd, it was like magic,” he would later write.

By the time he debuted for Memphis promoter Jerry Jarrett, the quartet was down to a duo; Borden and an intense, even for wrestling, competitor with an eye-popping, not quite human, physique named Jim Hellwig. The pair learned the business the hard way, travelling the backroads of America and working one-nighters in dodgy venues for low to no pay. But learn the business, they did. By 1988 the pair had gone their separate ways; Hellwig to the WWF as the Ultimate Warrior and Borden to Jim Crockett Promotions as Sting. On March 27th of that year, Sting wrestled what might still be his most iconic match, a time-limit draw with National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) heavyweight champion Ric Flair. “Everything changed after that night,” he would write.

It’s hard to express just what it was like to be watching that match in real-time. Sting wasn’t exactly a nobody, but he certainly wasn’t “Sting.” He entered the ring as something of an unknown quantity; not quite a Road Warriors-style anti-hero, not quite your standard white bread good guy. His bleach-blond hair should have made him a heel. His rat tail and flattop should have made him a punchline. It’s almost fair to say, in retrospect, that he was carving out his own space, even then, without anyone really knowing it. As the match progressed, and as his face paint peeled off from sweat and his chest grew bloody from Flair’s chops, you could feel his star shooting into the sky.

Find the video and watch it and see if you don’t feel a tingle when, with less than two minutes left in the match, Sting catches Flair coming off the ropes and rolls him over onto his back for a classic near fall. “Man, we’re talking inches, here…we’re talking inches from having a new heavyweight champion of the world,” shouts TV announcer Jim Ross. “A two-and-three-quarters count right there,” replies Tony Schiavone. It’s pure wresting magic.

By the end, with the match declared a time-limit draw and Flair left bloody and exhausted on the mat having just survived thirty seconds in the Scorpion Death Lock, Sting was over with fans in such a way that he would never need to worry about scrounging for work again. “Throughout the match, I could feel the mood of the people, and knew that they were buying Sting as my peer,” Flair wrote in his 2015 autobiography. “So was I.”

Though he may have once seemed to fit just a bit too neatly into the mold of the muscle-bound, one-dimensional bodybuilder, Sting’s work in the ring made it clear he was something more. His gracefulness made him appear sleeker and faster than he really was. His Stinger Splash, where he leapt, arms and legs outstretched, into opponents he’d trapped against the turnbuckles, could almost be described as graceful.

Dusty Rhodes labeled him “the franchise,” and indeed, Sting bore an outsized burden for much of the 1990s. He played a major role in keeping World Championship Wrestling in business during the Monday Night Wars, all while resisting offers to make a jump to the rival World Wrestling Federation.

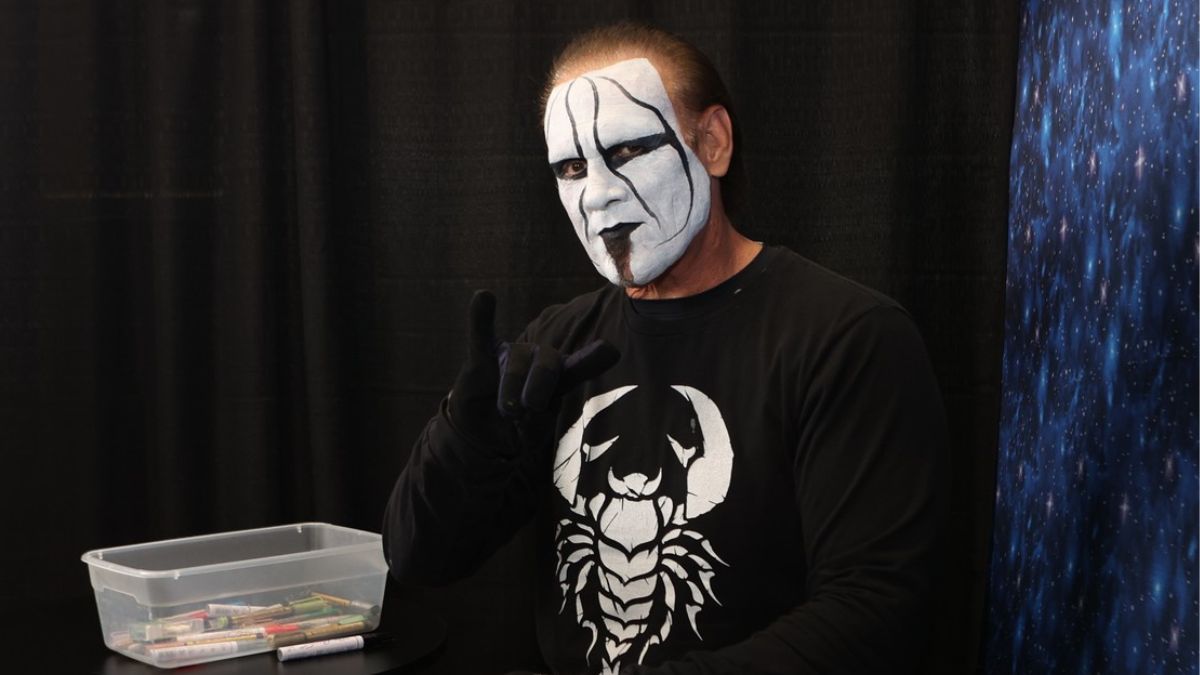

By 1997, when he wrestled Hulk Hogan in the main event of Starcade, he’d adopted a new persona. Gone was the multi-colored face paint and spandex. In its place was a stark black and white palette and brooding personality based on actor Brandon Lee’s character in The Crow. In anyone else’s hands, this new persona risked coming off as a bit silly and on the nose. In Sting’s, it worked like a charm. In all, he would win the NWA World Heavyweight Championship once, and the WCW World Heavyweight Championship six times.

He left wrestling in 1998 to focus on his health and family. Painkillers and all that comes with a decade of life on the road had taken its toll. Somewhat miraculously, he got clean and rebuilt his life. In 2001, when the WWF had emerged as the victor of the Monday Night Wars, he wrestled against Ric Flair in the final main event match for WCW’s flagship Nitro program.

Afterwards, he worked for a number of promotions, including TNA, AEW, and eventually, WWE, collecting numerous championships along the way. Though his guise and surroundings would change, he managed to always be Sting. In 2012, he was inducted into the TNA Hall of Fame. In 2016, he was inducted into the WWE’s. “He has been able to reinvent himself for years,” Kurt Angle said of him.

Sting learned the wrestling business the old-fashioned way before finding what looked at the time like overnight success. He worked with some of wrestling’s very best and added his own unique touches to what they taught him. More than anything, though, he brought a knack for reaching fans over the airwaves and making them feel a whole-hearted investment in his work. A wrestler can be shown any number of skills, but this is not one of them. As Sting told Grantland in 2014, “wrestling fans can see through somebody.” Though he didn’t even know what wrestling was for the first 20 years of his life, almost by magic, he would come to embody all the best things about it.

2024 CAULIFLOWER ALLEY CLUB HONOREES

- Iron Mike Mazurki Award: Sting

- Lou Thesz/Art Abrams Award: Kurt Angle

- Karl Lauer Independent Promoters’ Award: David McLane

- Jim Ross Announcers’ Award: Jim Ross

- Women’s Wrestling Award: Allison Danger

- Tag Team Award: The Dudley Boyz

- Men’s Wrestling Award: Buff Bagwell

- Lucha Libre Award: Negro Casas

- Red Bastien Friendship Award: Lori McGee Hurst

- Independent Wrestling Award: “Night Train” Gary Jackson

- Charlie Smith Referee Award: Bill “Fonzie” Alfonso

- REEL Award: Todd Bridges

- James C. Melby Historian Award: Jason Presley

- Courage Award: Black Bart (Rick Harris)

TOP PHOTO: Sting at the Contest of Champions: Where Heroes Gather fan fest, on Saturday, December 3, 2022, at RWJBarnabas Health Arena, in Toms River, NJ. Photo by George Tahinos, https://georgetahinos.smugmug.com

RELATED LINKS