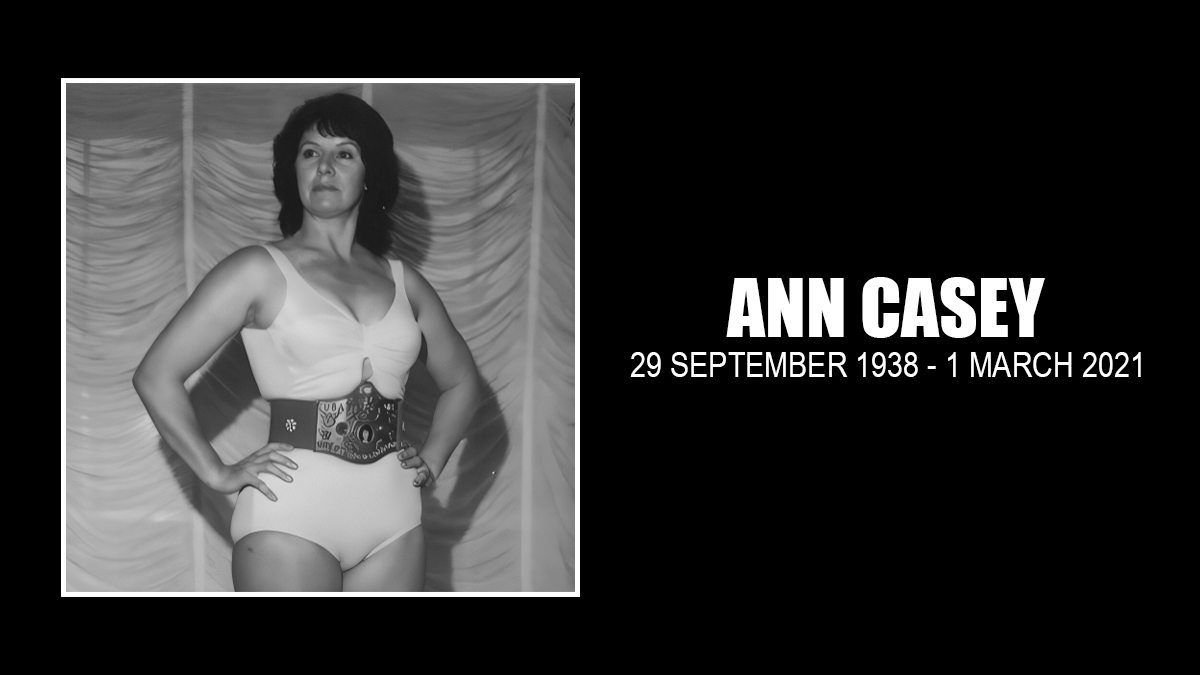

Ann Casey, one of the top women wrestlers from the late 1950s into the 1970s, has died. She was 82. But it’s such a rich story that it deserves a lengthy retelling — and she wouldn’t have had it no other way.

In 1950s-era rural Mississippi, “purdy young thangs” didn’t dream of wandering far from home, broadening their horizons, or seeing the vast expanse of the world. It was enough for their fathers to raise them and marry them to a decent fellow, since schooling and working were more for the boys.

And purdy young thangs most certainly did not wrestle other women in a pile of sawdust for chump change, dive through open windows to hunt down scofflaws, or ferry 18-wheelers loaded with hops from coast to coast.

Casey did all this.

When recounting the story years ago, Casey was constantly laughing. Her voice evoked images of magnolias and plantations and gentle southern nights. She knew that she once fit the Dixie definition of a purdy young thang, what with the shapely legs, polite manners, and all.

But somewhere along the line, something went awry. She led a life far removed from her childhood on a Mississippi cotton farm — a life of travel and trucking and bounty hunting, and, oh yes, hon,”rasslin’.”

“It wasn’t always easy,” Casey said in her buttermilk-rich drawl. “But I’m a survivor. And sometimes I just say to myself, ‘Well, now, Ann Casey … who would’ve believed it?'”

Born in Alabama and raised in Mississippi, Casey — her given name is Lucile O’Casey — was one of nine children. Her father, John, was a farmer and her mother, Viola, was a Creek Indian. In fact, Casey believes the Indian heritage in her maternal line gifted her with legs and calves as powerful as coiled springs.

“I have an extremely high Indian arch, and I could walk and run all day and my feet would never hurt,” she said. In fact, Casey didn’t just open and close the gates to the farm; she jumped over them. In training, she could dropkick a medicine ball held six feet above the ground. In practice, years later, she could deliver a standing dropkick fierce enough to dislodge two of fellow wrestler Natasha the Hatchet Lady’s front teeth.

Casey was a secretary and ticket seller for the Mobile wrestling office in 1962 when she went to the locker room after a show to pay the performers. The Fabulous Moolah (Lilian Ellison), the czarina of women’s wrestling and a shrewd judge of talent, took one look at Casey and immediately saw a potential addition to her stable.

“She liked me and saw the potential I had from the word ‘go,'” Casey said.

Casey, who had a young son from a brief marriage after high school, considered the offer, talked with other women wrestlers, packed her bags, and headed to Moolah’s training camp in Columbia, S.C. In the girls’ bunkhouse, she shared accommodations with a roster of future stars including Judy Grable, Fran Gravette, Brenda Scott, Sweet Georgia Brown, and others.

At 23, Casey was older, more mature, and more athletic than some of her fellow wrestlers. But, at 5’8 and a “beanpole skinny” 135 pounds, she hardly cast an imposing figure in the ring.

“The referee used to tell me, ‘Ann Casey, don’t stand behind the turnpost or I won’t be able to see where you are unless you stick your tongue out,'” she joked.

Casey broke into wrestling in a tag team match with Grable against Rita Cortez and Scott in Spartanburg, S.C., and eventually toured in Hawaii. There, she decided to split from Moolah’s camp, convinced she could handle her own bookings and clear a few extra bucks without taking Moolah’s marching orders.

Though Moolah represented the gold standard of women’s wrestling, Casey felt the legendary wrestler/booker demanded too large a cut of her wrestlers’ payoffs. “I was smart enough to get away on my own,” Casey said.

In the ensuing years, Casey attracted notoriety — and legions of fans — across the country for wrestling without boots. The shoeless style came naturally — by choice she always had spurned footwear as a child on the farm.

While she began her career in boots at Moolah’s suggestion, she discarded them permanently after a gimmick backfired. A pair of opponents double teamed her in a corner, tied her laces together, and heaved her under the bottom ring ropes to the floor.

Casey landed awkwardly and broke both ankles at one time, shelving her for a few weeks. “I told myself and everyone else that I’d never put boots on again,” she said. “If it was extremely cold and freezing, sometimes I’d keep boots handy, or out of respect to Judy Grable because that was her style, too. But from thereon, it was strictly Ann Casey Barefoot.”

Casey was one of the tallest female wrestlers of her time, and she preferred to square off with similar-sized opponents, if only because dropkicks from smaller foes tended to hit her — painfully — in the chest, instead of on the chin. She favored powerful rivals like Natasha, Brown, Susan Tex Green, and others.

“I never felt good wrestling girls smaller than me,” she said. “It never looked logical to me, much less the crowd, for [the 5’5] Moolah to beat these big girls like Sue Green, me, and Penny Banner.”

Invariably a babyface by looks, design, and nature, Casey shied away from playing the role of a heel. After all, fans just couldn’t imagine a wholesome country sweetheart pulling hair, gouging eyes, and screeching, “I don’t like y’all” at paying customers.

Green said that she enjoyed working with Casey, but thought their matches were limited by that fan response. “Ann Casey was a very good wrestler, but we were both babyfaces, we were both over, and the people just didn’t want to see us work heel.”

Casey’s rare forays into mat villainy were strictly unintentional. Appearing on a card near the Mexican border in the 1960s, she asked a wrestler to teach her a few words of Spanish to impart to the largely Hispanic audience.

She came to the ring, mounted all four turnbuckles, full of cheery smiles and graciousness, and found herself on the receiving end of all manner of debris: shoes, cups of ice, and beer cups. She retreated to the dressing room so security officials could quiet the crowd.

Confronting her linguist, she was shocked to find he had instructed her to say, “Hello, you cows … how fat you are!”

Her bond with children along the Texas-Mexico border near El Paso belied her heel status, as well. Casey would take her payoff, change it into $1 bills, buy some loaves of bread, and head to the Rio Grande. There, like ritual, children would see her familiar red Chevrolet Monte Carlo on the horizon, and start swimming across the river for some money or food. Casey made the contributions silently, by herself.

“Maybe that’s why I made such a bad heel,” she offered.

At times, she yearned for a less hectic life. As an independent contractor, Casey lacked basic medical or retirement benefits. As a single mother, she tried to stay as long as possible in one area so her son wouldn’t have to change schools during the academic year.

Her payoffs often didn’t come close to meeting her expenses. Slated to wrestle on an Indian reservation in Arizona, Casey became alarmed when her referee/driver couldn’t find the venue. She ended up tussling with her opponent in a pile of sawdust in the desert for meal money. The worst part was that she didn’t get any reaction from the fans. “We did everything in the book, but we couldn’t get them to do anything except grunt. That was about as ridiculous as it got for me.”

On the bright side, Casey’s southern belle charm got her attention from celebrities with whom she otherwise wouldn’t have crossed paths. One night in Oxford, Miss. in the late 1960s, Casey sailed through the ring ropes and landed in the lap of a handsome, redheaded young man in the front row.

As the referee started his count to 20, the man, making the most of the unexpected visit, politely inquired, “Hey, why don’t you just stay here for a little while?”

Responded Casey, “Maybe later, hon, but I’ve got to get back in the ring and whip this girl’s butt.”

Casey said she thought nothing about the encounter until she met up with another wrestler backstage after the match, who enlightened her about the heartthrob that was the star Ole Miss football quarterback.

As she remembered the explanation, “‘Ann Casey, do you know whose lap you were sitting in? Why, you were sitting in Archie Manning’s lap!'”

Manning wasn’t the only southern icon that Casey met. While she was waiting for a match in the backstage area of a coliseum, Elvis Presley walked into the dressing room, paper bag in hand. Casey recounted that Presley asked if she was that wrestling gal from Mississippi?

“Yes, sir, I am,” she declared proudly.

“Well, neighbor, being that we both are from Mississippi means we both love to eat pickled pigs’ feet,” Presley responded. The two chowed down on the delicacy, and Casey later received a white fur coat, inscribed to her “from Elvis.”

One of Casey’s regrets is that Moolah seldom shared her world championship with other wrestlers, as she reigned virtually uninterrupted from 1956 to 1986. However, in 1974, Moolah wooed Casey back to her entourage, enticing her with a switch of the U.S. women’s title.

The belt swap happened inconspicuously in a small town in South Carolina. Casey went on the road with the belt, and stayed with Moolah’s troop for about a year.

By the late 1970s, though, her appearances in the ring became more infrequent as she spent more time tending to her daughter, Casey Jr., and working for the Mississippi Forestry Commission.

Most importantly, she returned to school and earned the education she never received as a youngster. She entered the University of South Alabama in Mobile in 1985 and graduated in 1990 with a degree in criminal justice.

“Oh, it was difficult after being out of school for so many years to go back,” said Casey. In particular, a physics course with a professor from India gave her the fits because “he couldn’t understand my Scarlet O’Hara accent and I couldn’t understand his.” But Casey kept at it until she passed the course.

While she considered attending law school, the cost was out of her range, and so was the time commitment. She and her daughter moved to Jackson, Miss., where she worked as a psychology technician and later as a bail bond officer.

“We had to go arrest a woman who had missed going to court,” Casey said. “So she knocked on the door, and she ended up throwing an iron at me and dove through a window to get away.”

Casey went to the window, where the woman, in true Moolah-like fashion, pulled her hair. They went tumbling into a bed of red ants, and, as if in a cartoon, the bail skipper started ferociously jumping and scratching.

“That’s one time my rasslin’ skills came in real handy,” Casey said.

In 1998, she hit the road again, driving for Jim Palmer Trucking, a huge national transportation firm headquartered in Montana. Casey logged thousands of miles behind the wheel, and found the pay more than acceptable, grossing more than $30,000 a year.

Not a bad deposit compared to rasslin’ on the Indian reservation, even though it involved hauling beer hops from Washington state across the country to the Anheuser-Busch brewery in Williamsburg, Va. “I’d get drunk just smelling the mess,” she said. She left the company after too many miles and too much truck stop food to improve her conditioning and get in shape — she actually dreamed of wrestling again in 2004, around the time the Cauliflower Alley Club presented her with its Women’s Wrestling Award.

Interviewed before the presentation, Casey was typically modest.

“I never thought I was better than other people,” Casey said. “Had I had enough education, I probably wouldn’t have gone into wrestling,” she said. “But my father was like a lot of fathers of the time in that he saw women doing other stuff and getting married, and he didn’t send us to school like our brothers. So I did what I did.”

Health-wise, Casey had a heart attack in 2005, which slowed down her lifestyle. Only a week or so ago, she fell and was hospitalized.

Casey was an early adopter of the internet and had a fan support group on Yahoo for a time, and later kept fans updated on her life on Facebook.

Her last post, from February 16, 2021, was grim:

Ann Casey Says…I am very sick…

Thank you Brother Kelly, for posting this song for me, it is one of my all time favorites…(from when I lived in Gatlingburg,Tenn.)

I am, at this time, undergoing test for the “Big C”…!

As most all of my friends know, I do not come on Facebook, show pics of myself in a hospital bed, and complain about ill health, from a bad headache, heart attacks, or whatever…!

I do try to come on Facebook each day to send out birthday wishes, check friend requests, and YES, to keep up with our great President Trump…! Sending Love & Blessings to everyone…! Ann.

Casey self-published two volumes of her autobiography, The Lady, The Life, The Legend, in 2009, though they are photocopied packages rather than bound books.

Her cousin, Brent Casey, shared the news of Ann’s passing on the afternoon March 1, 2021.