There was a time when “Butcher” Paul Vachon was one of the most recognizable names in professional wrestling.

From his home in Masonville, Quebec, it is less than four miles south is North Troy, Vermont, the closest United States-Canada border crossing. Vachon lives with his wife of 27 years, Dee, in a seniors apartment complex of 60 units.

From his window, Vachon proudly tells of being able to view the land that he and his 12 siblings grew up on.

Decades back the former co-holder of the AWA World Tag Team Championship with his brother Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon, first faced serious health issues. Battles with colon and throat cancer were overcome. Reconstructive jaw surgery was also a challenge the Butcher endured.

Both his spirit and memories of wrestling travels, some more than a half century ago, remain fresh and energetic. As our 45-minute telephone conversation progresses, Vachon informs me that he has kept to a two-hour exercise program daily for the past year.

At 83 years old, with all the ups and downs associated with life in wrestling, beginning in the late 1950s until mid-’80s, Vachon is positive with what today and tomorrow may bring. He is peddling on a mini-exerciser during our trip down memory lane.

“I feel pretty good considering the life I’ve led,” says Vachon. “I have three good meals each day.”

Keeping busy seems to be what allows Vachon to remain young at heart.

During our conversation, Dee sounds close to the portable phone that she passed on to her husband. Dee, 14-years younger than her famous spouse, is attentive to his needs. A former Marine staff sergeant, she was instrumental in having a fans page set up on Facebook for the Butcher. For those who want to make a reconnection with their wrestling hero of years ago now could do so, and the page also offers therapy for Vachon to have their company.

For 20 years, Vachon and Dee traveled to fairs and flea markets selling his memorabilia — books he authored, T-shirts, pictures, walking sticks, and other items.

They are very much a team.

Dee and Butcher.

“Here’s how I met Dee,” the Butcher offers, tongue firmly planted in cheek. “She had never been to the wrestling matches, and never had been married. I promised myself that I wouldn’t marry again. I met Dee in a bar, took her home, and body slammed her on the bed. She said, ‘This is probably not the first time that you have done this.'”

A post-wrestling ritual Vachon has been committed to for the past two decades is playing the role of Santa Claus at a nearby mall.

Each Christmas season, the Vachons would depart from their hamlet of less than 2,000 residents, make the 75 miles drive south across the U.S. border to Berlin, Vermont. At the Berlin Mall, the man who earned his living as the Butcher in a wrestling ring, did a complete about-face, and brought cheers to children.

Online Santa Butcher.

However, due to COVID-19 restrictions, including a closed U.S.-Canada border, this past Christmas season brought a new challenge for Vachon. Santa Butcher made his appearances and promises to kids via a 55-inch flat-screen television.

“From my apartment, there was an elf at the mall introducing me. The kids seemed to have a good time,” said Vachon.

With pause, Vachon proudly describes some of his world travels, and those who he came in contact with in wrestling. Traveling meant personal sacrifices. Being on the road, as he estimates easily 80,000 miles annually, kept the Butcher apart from his family.

He has a half dozen children, three boys and three girls. They are spread continent-wide, in Florida, Georgia, and Alberta, all a considerable distance from the man they had to share with thousands of wrestling fans booing or cheering him nightly at wherever his work took him.

There are no regrets.

“You have to really be off your rocker to really want the lifestyle. By some miracle, and my body could be young again, I’d do it all over again — for free,” Vachon explains.

Calling himself a “farm boy,” and having grown up just three miles from his current residence in Masonville, Vachon boasts of having traveled to 40 countries during his career. Fulfilling his dreams as a child to see the world, carefully, Vachon offers highlights of people and events that remain special to him.

As the 1970s arrived, and the Vachon Brothers were on top in the AWA, offers were made to the duo to join Grand Prix Wrestling based in Montreal. This was a difficult business decision for the Butcher and the Mad Dog.

“When me and my brother were approached (by Grand Prix) to come to Montreal and run opposition to the Rougeaus, at first, I had hesitations. Me and my brother were making good money for that outfit (AWA),” recalls Vachon.

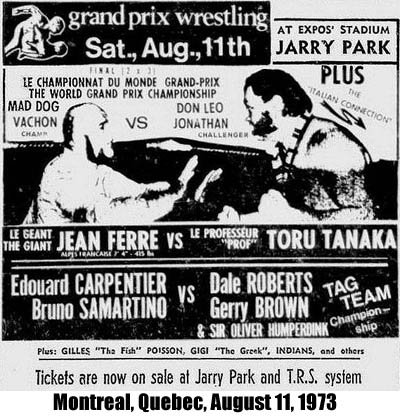

“(Grand Prix) wanted to make my brother a partner. I would be in the front office. I was asked to apply for a license to run the Montreal Forum. I wouldn’t be able to wrestle, if I was the promoter. So, my brother offered me half of his partnership. When Grand Prix was created, we ran from Newfoundland to British Columbia, and in summers we ran Jarry Park in Montreal.”

In July 1973, at Jarry Park, Grand Prix ran its first big show at the outdoor baseball stadium, and drew 29,000 fans. The evening’s main event was Mad Dog versus Killer Kowalski for the championship. One month later, 12,000 wrestling fans showed up at Jarry Park for Mad Dog and Don Leo Jonathan in the main event.

My two favorite, personal memories of Butcher Vachon occurred in the 1970s, during his WWWF touring.

The first was in July 1975. Boston’s Hotel Madison, attached to both the North Station and Boston Garden, is where the annual Wrestling Fans International Association held its convention. I was among the attendees.

Traveling from New York City, I was more than anxious for what was planned. Meetings with fans from around the country, regional merchandise for sale from promotions I only read about in magazines, and getting to meet some WWWF stars up close was on the agenda.

There was a WWWF show booked in the Boston Garden and the main event saw Bruno Sammartino take on Spiros Arion in a cage match.

Word came that the WWWF wasn’t going to send any of its talent to meet the convention fans. This was a time when the wrestling business was closed to outsiders. Manager The Grand Wizard (Ernie Roth), who lived in the Boston area, did attend, and was wonderful in answering questions, signing autographs, and being a great ambassador to the business, even if he was a heel manager at the time.

On the final day of the convention, Sunday morning’s scheduled goodbye gathering turned into another great memory for me that I hold dear today. In the convention room, unannounced, came Butcher Vachon. Cigar in mouth, the bearded behemoth strolled in, and stepped up to the dais.

Taking questions, and later posing for pictures with many happy wrestling fans from Los Angeles, to Kansas City, to Brooklyn, the Butcher concluded the convention on a high. Vachon proved to be a positive example of how a professional wrestler can and should carry themselves.

Three years later I came across Vachon in Springfield, Massachusetts, at my friend Tom Burke’s home.

On January 21, 1978, the WWWF had a show at the Springfield Civic Center. The second match, on the card headlined by Bob Backlund defending his WWWF title against Professor Toru Tanaka, had Vachon defeating Frankie Williams.

Traveling with the Butcher that evening was his then-wife Rebecca and her teenage daughter Trudie (who would go on to a successful wrestling career as Luna Vachon). After the matches, the Vachons made their way to Burke’s home / wrestling museum.

Once settled in the upstairs apartment, the Butcher entered Tom’s office, and took a keen interest in the international wrestling posters that covered all four walls, and added a signed 8×10 photograph to be placed where space was available.

I shadowed both men, and squeezed in a few questions for myself. The hour or so that I had in the presence of a wrestling giant as the Butcher remains priceless.

When attending WWWF shows in Albany’s Washington Avenue Armory, or Bangor, Maine, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and the Philadelphia (PA) Arena, I always paid close attention to the bald-headed Butcher. Not fast as a Dean Ho or Chief Jay Strongbow, or not dropkicking as Victor Rivera and Tony Garea, Vachon just did what wrestlers do — try and win at all cost.

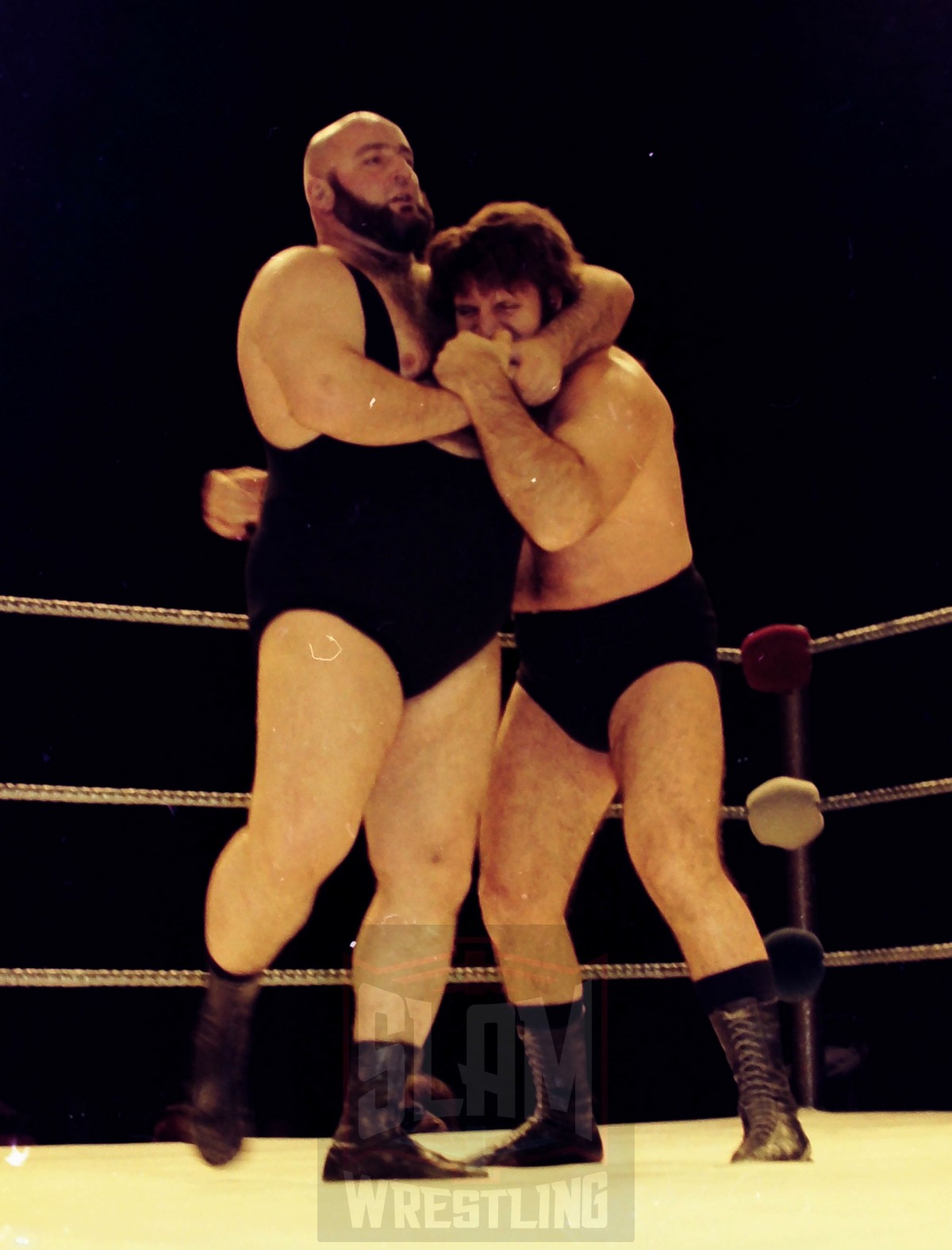

Butcher Vachon has a headlock on Bruno Sammartino in WWWF action. Photo by John Arezzi, www.matmemories.com

I saw him main event against then WWWF Champ Bruno Samartino at Long Island’s Nassau Coliseum. I have watched film of the Vachon Brothers coming to Madison Square Garden on March 26, 1973, to work with the team of Louie Tillet and Don Curtis. I saw him work in singles matches with Andre the Giant.

Vachon was a wrestler from my era that was believable. He looked and talked mean. He pummeled his opponents with kicks and punches, and a few chokeholds added in his repertoire. That was all I needed to believe. The Butcher was the real deal.

There is a French-language documentary film by director Thomas Rinfret, Les Derniers Villains, which is an account of the Vachon wrestling dynasty. For four years Rinfret followed the Butcher around to capture his travels and innermost thoughts on his life, and his family’s contributions to the wrestling game.

Speaking with one’s heroes is always a treat, even magical at times. One year shy of having attended my first live wrestling show 50 years ago at Sunnyside Gardens in Queens, New York, the few moments I had, one-on-one with one of my earliest childhood wrestling idols, remains ever so special.

In my mind, Paul Vachon will always be larger than life, only a body slam away from taking me back to being 13 years old, and believing what I saw in the ring.

RELATED LINK

Another well written, heart-felt story!! Butcher is a legend in wrestling as Donny is in journalism!!!

If my memory is correct the Butcher enjoyed sharing his singing talent with attendees at various wrestling banquets. Great article about one of Bruno’s foes.

That was a great article. Learned many new things about the Butcher.

I had the pleasure of meeting him back in the early 2000’s. The first thing that impressed me was his handshake it was strong and sincere. I truly believe he is the strongest man I ever met. Even more, he was friendly and down to Earth, very kind man and fascinating to talk to. Highly intelligent too.