In the Tennessee wrestling territory known for over-the-top, anything-goes action, Len Rossi was an anomaly.

He was a plain-and-simple babyface, not given to shrieking, hollering, or playing to the crowd. He was the son of Italian immigrants at a time when Tennessee was anything but a melting pot. He was a native of New York state, looking for acceptance in an area where he was the one with the funny accent.

Rossi, who died October 9, 2020, at 91, also was the biggest pro star that Nashville and the adjacent area has ever known, thanks to a sincerity that carried from real life into his wrestling persona.

“This is going to sound very immodest of me and I don’t mean to have it sound that way,” Rossi said in one of many interviews with SLAM! Wrestling.

“I’ve seen guys come and go, all types of gimmicks, blond hair, bald heads, fancy outfits, fancy uniforms, I’ve seen ’em come and go and everybody was amazed because all I had was a little warmup jacket that cost maybe two bucks — nothing fancy, not bragging, but I just think I did things in the ring that people believed in. I worked real, real hard, and very convincingly and my interviews were always very modest.”

Rossi wrestled as a pro for more than 20 years until injuries from an automobile accident in December 1972 effectively ended his career. By most counts, admittedly imperfect, he held the Southern Junior Heavyweight title six times and the Southern/Mid-America Tag Team title 16 times with partners ranging from Jackie Fargo to Bearcat Brown, with whom he integrated southern tag team wrestling.

Veteran star Frankie Cain said many fans did not recognize the genius of Rossi in the ring, where he could a quality match out of poorly skilled opponents and make them look good in doing so.

“You had to be a damned near genius in the ring after they was worn out, which didn’t take long, to go in and have a match with them. Len Rossi could certainly do it,” Cain said.

Les Thatcher mourned the passing of his friend, as well, noting on his Twitter feed that Rossi, the 2004 winner of the New York State Award from the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame, represented the consummate babyface.

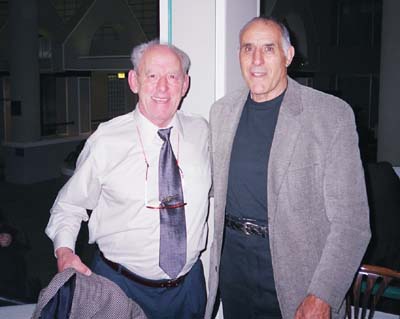

Len Rossi and Dominic Denucci at the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame induction in 2004. Photo by Greg Oliver

“One of the smoothest ‘workers’ I have ever seen, a gentleman, always pleasant, friendly, and willing to help youngsters. A true Nashville legend,” Thatcher wrote. “Those of us honored to call Len friend are better for it, and the way he carried himself he also made us proud to be pro wrestlers.”

A TOUGH START

The son of Italian immigrants, Len Rositano was born September 24, 1929, in Utica, New York. His motivation for entering the mat game came largely because bullies beat him up in school. By 14, he was lifting weights at the local YMCA to match their strength. When it came to wrestling, though, he would walk by the mats and dismiss it as a bunch of baloney until he met a wrestling coach named Eddie Zysk.

“He asked me, ‘Why don’t you come out for the team?’ I kept putting him off, putting him off. Finally, I said, ‘I’ll try it,’ thinking that I could destroy this guy. Well, he took me down and rode me like a mule, up and down. No matter what I did, he would take me back down. So I fell in love with the sport of wrestling.”

There was no high school wrestling at the time, so Rossi competed against teams from other YMCAs. When he was 16 and 17, he made a few bucks on the side in unsanctioned smoker matches, so-called because the room was rife with cigar and cigarette smoke.

“The spectators, the men, they’d throw 50 cents or a quarter, half a dollar, into the ring, and we’d all split that. It was chicken feed, but it was a lot of fun. But every once in a while, some of the guys that were drinking would jump in the ring and you’d be fighting for your life. It was like a street fight. They wanted to test you. Now that I look back, it was fun, but it wasn’t fun at the time, you got beat up.”

But that background, plus several boxer-versus-wrestler amateur matches, gave him a solid foundation for the self-defense he would need as a pro wrestler.

“If an outsider jumped into the ring, you never knew what he would do, so you learned how to fight. Boxing, keep your hands up at all times, takedowns, go-behinds, things of that nature. It was more like a street fight at that time, and you just learned how to take care of yourself,” he said.

For that matter, Rossi recalled the YMCA wrestling as a little harder than modern-day high school wrestling because of the level of opponent. “I was 15, 16, 17 years old, and I might wrestle somebody at the same weight, but he could have been 30, 35, 40 years old, a lot more experience, so you really learn the hard way.”

It was enough to convince Rossi to give pro wrestling a whirl not long after his 20th birthday. He drew nothing but rebuffs when he tried to market himself to promoters until the timely intervention of wrestler Jackie Nichols, who he befriended at matches in Utica.

“All the promoters wrote back, ‘Sorry kid, you’re too young.’ ‘Sorry, you don’t have any experience.’ ‘We’re filled up.’ I couldn’t get booked. So I shared this with the wrestling friend that I made, Jackie Nichols. … Jackie told me, ‘I can get you booked in Boston.’”

His first few years were nomadic; he recalled living on peanut butter and during a short swing through the Northwest, sending his wife two or three dollars at a time. In an effort to put some excitement behind him, promoters billed him as a product of St. Louis, Missouri, even when he was wrestling in upstate New York near Utica. Even his name was insufficient — a Boston promoter shorted Rositano to Rossi so his name would fit on a poster.

Rossi persevered and got into his first big feud in 1954 and 1955 with Gypsy Joe in the Utah-Idaho area. It culminated in a scheduled 10-round boxing and wrestling match — that YMCA training was useful — in Provo, Utah, with Rossi winning on a sixth-round knockout. From there, he wrestled in the Illinois-Wisconsin region, Texas, and New York before heading to Tennessee in May 1958 for what was supposed to be a two-week stint before a tour of Canada.

SOUTHERN SUCCESS

“When I came [to Nashville], my deceased wife [Lee] said, ‘Joey is going to start school pretty soon and I’m not going to be traveling all over the country to go to school.’ So we decided to settle here,” Rossi said. He also made the acquaintance of Tex Riley, a true character known for falling asleep in the ring, but someone who also taught Rossi the value of showmanship.

“Tex was the one who really taught me not about moves, but about psychology,” said Rossi, who tagged with the older hero for several years. “It took years to become a good professional wrestler. Not only do you have to take care of yourself in the ring, but you have to be a crowd-pleaser, because we depended on the public to feed us, of course.”

For Rossi, that meant a clean, believable style, mixed with just a touch of out-of-region intrigue to capture the hearts of southern wrestling fans. Tennessee sportswriter Kent Gardner once described him as “a taut-muscled athlete with a curiously urbane face, who looks more like a school teacher than a wrestler.”

“He was different than what they were used to seeing down here,” explained the late Billy Wicks, a top Tennessee star. “He was a Yankee coming down to Tennessee and that wasn’t easy. I think he was a good Italian—‘Len Rossi, eh, eh’—and everybody likes a good Italian. That was part of it and then he was a good, clean-cut wrestler who believed in the rules, was polite and respectful.”

Rossi used the Boston crab and sleeper hold as his tactics of choice, never varying from his role as a babyface as he starred in the territory operated by promoter Nick Gulas.

“My deceased wife and I, it was very difficult to go out and eat, Tennessee, Kentucky, Mississippi; any place the TV wrestling as shown, you could not believe the enthusiasm here in the South. Now, back then, there was only two or three channels so I’d jokingly say you had to watch us. But I was on TV for 20 years. No matter where you went, they’d mob you; it was unbelievable.”

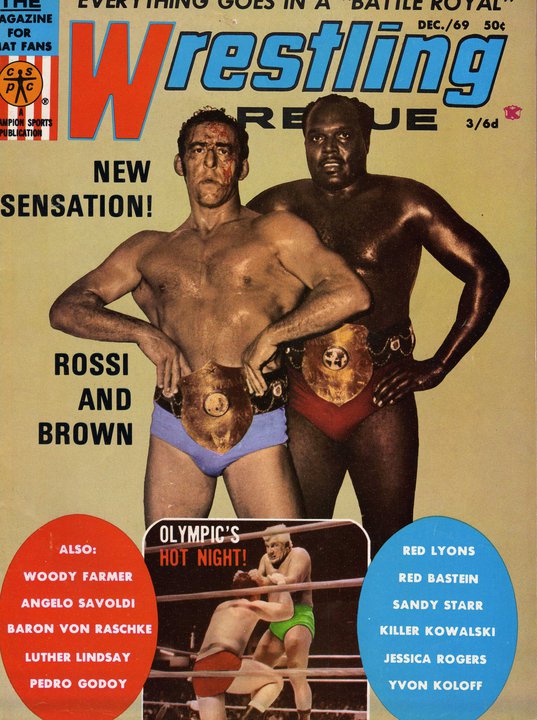

With his stature as the uncontested good guy, Rossi was the perfect partner for Bearcat Brown (Matt Jewell) as they worked from 1969 to 1972 as the first regular integrated tag team in the Deep South. Before their first match in Birmingham, Alabama, Rossi remembered bomb threats and opposition from the Ku Klux Klan.

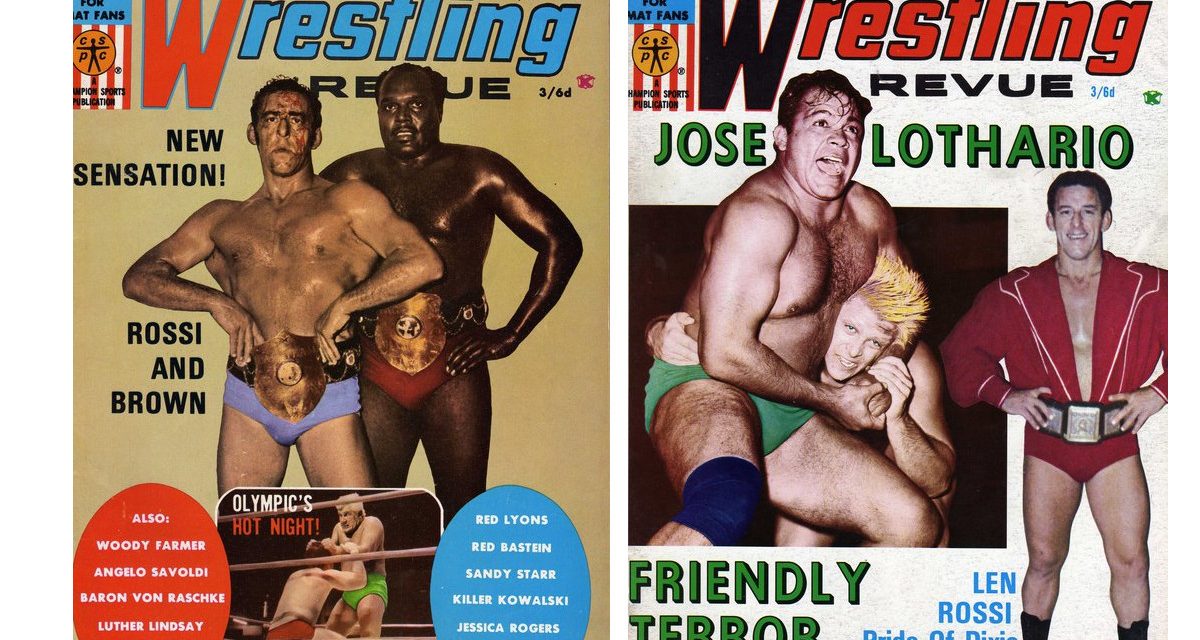

But the team won over even skeptical wrestling fans, especially after the dreaded Interns whitewashed, tarred, and feathered Brown. “He went on TV hollering, ‘I don’t want to be White. I’m black and I’m proud to be Black,’” Rossi said. “That earned him a measure of respect from all quarters.” In a rarity for the day in both integration and publicity for Southern wrestling, the duo made the cover of the December 1969 issue of Wrestling Revue.

As the late Buddy Wayne observed: “Bearcat, all the Black people could come to see him. And Rossi, all the White people could come to see him. So when Rossi would tag Bearcat, the black people would go crazy and vice versa. It was a great combination.”

Rossi’s son Joey went into wrestling, but a long run as a father and son team was not in the cards. Rossi was involved in a serious accident on December 8, 1972, that broke his feet, arms, ankles, and legs. Though he attempted a brief comeback, he was miserable. No formal education, no trade. He started drinking heavily to cope with his injuries. He developed colon and stomach problems and passed out at home. At a hospital, doctors diagnosed him with diverticulitis, which was a blessing in disguise.

“God works in strange ways. A man came into my room — this is back in the ‘70s — and he closed the door and said, ‘Len, you don’t know who I am, but I’m the radiologist that read all your reports. You do not have a life-threatening situation. … This can be treated with … diet and medicine.’”

Rossi was hooked on something other than wrestling. He became a vegetarian and studied nutrition at Belmont University in Nashville. “It was awful. My deceased wife said, ‘How’d you do at school today?’ I said, ‘Hell, I failed registration.’ I just followed the kids, whatever they did, I did. But I got to where I enjoyed it. But it’s funny when you have to re-learn how to study.”

Around 1973, Rossi and his wife Lee set up a natural health food store in Brentwood, outside of Nashville. He earned a doctor of naturopathy degree and specialized in natural healing for the rest of his career. Not to minimize his mat career, but promoting healthy lifestyles, he said, was more rewarding than crushing bones.

In 1982, Nashville Mayor Richard Fulton honored Rossi with a plaque in appreciation for his “contributions to the field of athletics, promotion of good sportsmanship, and continued support of sound nutrition benefiting all residents of Nashville.”

“We introduced, in my opinion, natural healing, healthy living and lifestyle here in this part of the country,” Rossi said. “We pioneered it. That was before Whole Foods was born and GNC and all that.” The business continued until a road-widening project cost him his facility a few years ago. Undeterred, he sold vitamins from home, using his garage as a warehouse.

“You learn to want to do something and love something, whether you’re going to be a mechanic or a carpenter or an electrician,” he said. “You want to be the best that you can at your own particular trade. My goal was to be one of the best in the business at that time.”

Rossi was preceded in death by his first wife, Lee, son Joey and daughter Adele. His wife Jeanie survives. Funeral arrangements were incomplete at press time.

RELATED LINKS

- May 9, 2004: Hall of Fame grows some more

- Dec. 1, 2003: 1970s wrestler Joey Rossi dies of cancer