The death of “The Dynamite Kid” Tom Billington came on Tuesday, his 60th birthday, his health battles post-wrestling front and centre for years, proof that there was a huge price paid to be one of the most innovative, influential professional wrestlers in history.

How influential was he? Even the curmudgeonly Bad News Allen Coage once gave Dynamite Kid props: “Pound for pound, Dynamite Kid was probably the best wrestler ever because you’ve still got these young guys today trying to emulate him in the ring. He was one of my favorites to work with. In our matches, the people just really wanted to kill me and just come in there and help him out.”

The late Owen Hart, in one of his interviews with SLAM! Wrestling, said that growing up, he placed Dynamite Kid “on a pedestal … I’d go ‘Wow, that guy’s awesome.’ … Dynamite, just because he was the original, was the best.”

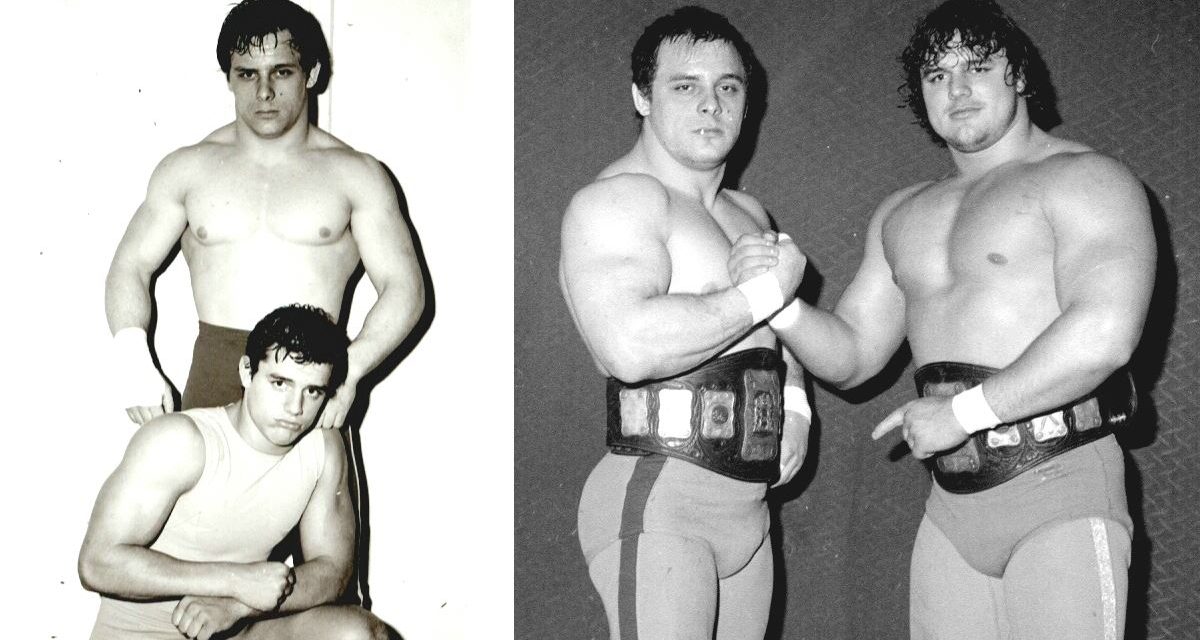

Manager John Foley with Dynamite Kid in Stampede. Photo by Bob Leonard

But the flipside of his legacy is equally lasting. As Dave Meltzer wrote in the Wrestling Observer Newsletter in 1994, that Billington was “a pioneer of insane bumps whose career was cut short by a crippling back injury no doubt related to his risk-taking, admitted blowing all his money on drugs, booze and women, claiming when he was in the WWF he drank himself silly, needed drugs (cocaine, Valium, speed and steroids) to survive the pace, get the sleep and keep his physique.”

Billington was born December 5, 1958, in Golborne, Lancashire, in a family with two sisters and a brother, where their father, Bill, was a coal miner, and their mother, Edna, was at home. Bill Billington and an uncle, Eric, had both been boxers, and his grandfather Joe Billington competed as a bare-knuckle boxer. Like his predecessors, Billington learned to box too. At the wrestling matches in Wigan, Billington met trainer Ted Betley, who ran a wrestling school in his home. The 5-foot-8 Billington set on a new career path.

Debuting in 1975 and named Dynamite Kid by promoter Max Crabtree, his early days in England as a wrestler were tough, though the weight-class system allowed him to have competitive matches. For a time, he was the much smaller tag team partner to the iconic, massive Big Daddy.

Calgary’s Bruce Hart toured the United Kingdom in 1977, met Billington, and suggested he should travel to Canada to compete for Bruce’s father’s promotion, Stampede Wrestling. “I think I told Stu he weighed about 170,” said Bruce Hart. “Stu said, ‘Eh, pretty fucking small. Is he a fucking midget?’ We had a whole bunch of these big, sluggish kind of dinosaur types at that time, John Quinn and that type. We weren’t doing great business. … I kept insisting and Dynamite was anxious to come.”

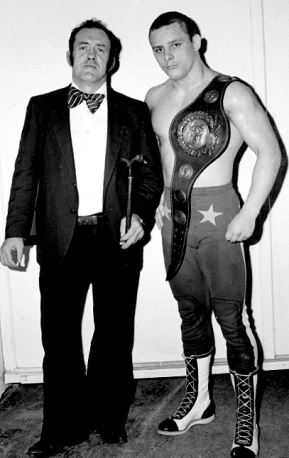

Not long after, another Englishman, Davey Boy Smith, came too; Billington and Smith knew each other, though not well initially; Billington’s father was the brother of Smith’s mother, but the families were not close.

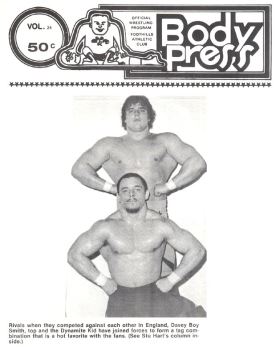

A Stampede Body Press program dated March 17, 1978 hyped Dynamite Kid’s arrival:

Making his North American debut next week will be a remarkable yung athlete known as the Dynamite Kid. The Wigan product has compiled an impressive winning streak, capturing the British Empire and International Jr. Heavyweight championships, and defeating many of Europe’s best.

The British, in recent years have produced several of the finest grapplers ever seen in these parts, so many observers are anxious to see whether the Dynamite Kid will follow in the tradition of the other great Brits. One who might know is Dory Funk Jr., great former world champion, whose battles with Billy Robinson, Les Thornton, and Geoff Portz were classics. Funk recently had an opportunity to see the Dynamite Kid in action while vacationing in London. He came away impressed. Says Funk: “Simply amazing. This youngster has some of the most incredible moves I’ve ever seen in the ring. My impression is that he’s going to be a great one. I believe I’d have to rate him right up there with Robinson, Portz and the rest. When he grows up and gains valuable experience, he’s going to be something else.”

In Stampede, Billington was a quick learner, working with talent from near and far, including grizzled veterans like Duke Myers, and their tag team was managed by another Brit, John Foley.

Myers, who died in 2015, once shared his memories of Billington. “He did things that people tried to copy, and he was good at them. He made them look so easy that everybody wanted to do it. He was a hell of a worker. He was also a good shooter,” said Myers, chuckling over Billington’s unpredictable nature. “He would not hesitate about cracking a fan.”

Dynamite Kid and Davey Boy Smith on a Stampede program in March 1984.

The unpredictable tough guy aspect of Billington never left him, and WWF lore is full of stories of his violence and mean ways. That was very evident in Calgary, said Myers. “I’ve seen him do some stuff that was unreal. He’s got an attitude. If you don’t know him, he’ll tell you to buzz off — that’s the light way of telling you that. On the whole, he doesn’t like people.”

Before the WWF run, Dynamite Kid never worked much in the United States, aside from Stampede ventures across the border, and in the Pacific Northwest, where Dutch Savage brought him into Portland, Oregon. “I got Tommy his first green card to come into the Portland territory back in the early 1970s,” wrote the late Savage on his website. “He came and no one really knew him, but I saw some box office talent in him. Great worker and a real fine gentleman. I knew he was going to go far in the U.S., it was just a matter of time. The rest is history.”

The matches that put Dynamite Kid on the map, no question, were his series of bouts with the original Tiger Mask (Satoru Sayama). It began with Billington’s first tour of Japan, for New Japan Pro Wrestling in July 1979, and he was quickly challenging for Tatsumi Fujinami’s WWWF World Junior Heavyweight title. Tiger Mask-Dynamite Kid, feuding from 1981 to 1983, put the smaller wrestlers in the spotlight, and their battle at Sumo Hall in Tokyo on April 23, 1983 was Wrestling Observer Match of the Year.

“His matches with Tiger Mask in Japan were 20 years ago, but if they took place today people would still be going crazy for them,” Chris Benoit once said.

In May 2018, Tommy Dreamer recalled being a young boy seeing the Tiger Mask-Dynamite Kid bout from Madison Square Garden on television. “I was like, ‘What in the world am I watching?'” recalled Dreamer. “I was like, ‘These guys are so much better than these other guys, because of the moves that they’re doing.’ And if you go back and you watch now — and I do, every day watch stuff on the WWE Network, there are some guys that are stars that couldn’t be the worst independent wrestler of all-time, and they were stars! Because the business was different, the business changes, the business evolves. So from the same times where I believed that match, Dynamite Kid and Tiger Mask, which was at Madison Square Garden, where I’m sure they came to the back and they were like, ‘What the hell are you guys doing?'”

As the World Wrestling Federation expanded in the early 1980s, it gobbled up territories and talent. Though the deal WWF honcho Vince McMahon made to buy the Hart’s Stampede promotion never really came to fruition, WWF did take its top talent, including Smith and Billington In 1985, the pair met with McMahon and booker George Scott in a Toronto hotel, and Vince suggested the British Bulldogs as a name. “And if I think about it, what with the steroids, and our mean-looking faces, I suppose we did,” wrote Dynamite in his autobiography. The newly-baptized Bulldogs, with their Union Jack outfits, didn’t sign a contract at first and continued going back and forth to Japan, having made a lucrative jump to All-Japan.

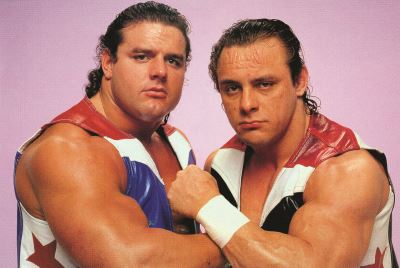

The British Bulldogs in WWF.

Showcased across the world as the WWF brand grew, fans were astounded by the Bulldogs’ Japanese-influenced style, a far cry from the plodding Iron Sheik-Nikolai Volkoff tandem. “They made everything look so real that it was always scary to get in the ring to take bumps. When I knew a spot was coming up, I’m going, ‘Oh, fuck,'” said manager Jimmy Hart. “The way they’d always snap into everything. … It was just crisp, everything they did. The punches looked good. When both of them were healthy, what a super team.”

“I think the British Bulldogs were more revolutionary in Japan than North America,” said Meltzer in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Tag Teams. “Their hard wrestling style didn’t fit in with a lot of the WWF teams at the time, whereas the Japanese wrestlers and style made them seem more special. I think their impact was strong among hardcore fans and a lot of people who grew up to be top wrestlers. It’s funny, because at the time, the Road Warriors were the kings of tag teams and everyone wanted to be like them … but long-term, it was the Bulldogs and Midnight Express who popularized the big move style that the next generation of wrestlers studied.”

The Bulldogs were assigned a bulldog mascot in Matilda and a manager in tag team expert “Captain” Lou Albano. Programmed against the veteran Greg “The Hammer” Valentine and his partner Brutus Beefcake, the Bulldogs fought the WWF champs around the horn leading up to WrestleMania II, where they won the titles for the first — and only — time. “Davey Boy was just kind of a musclehead. He was a follower, but he was a good follower, a good athlete,” explained Valentine. “Dynamite Kid, he really knew how to work and he liked to fly.”

The price was high, however, to look bigger, explained Jim Brunzell of the Killer Bees. “Davey got on those damn painkillers and ended up [dead in 2002],” said Brunzell a decade ago. “Tommy is crippled. And Tommy didn’t take care of his body, either. He was probably a legit 160-pounder, and he was using anabolics [steroids] to get up to 195, 205 pounds. He was ripped, but at the same time, I don’t think it helped his general physical well-being.”

The date December 13, 1986 marked the turning point in the history of the Bulldogs. It’s the day that Dynamite Kid hurt his back in a match with partner Davey Boy Smith against Don Muraco and Bob Orton Jr. in Hamilton, Ont., during a WWF match. While in a Calgary hospital after a six-hour operation to repair two ruptured discs in his spinal column, Dynamite told the press that he didn’t expect to be back anytime soon. “The rules say we have to defend out title within six months and unless something miraculous happens, I won’t be able to wrestle by then,” he said.

Yet, on January 26, the Bulldogs were back in action in Tampa, Fla., in order to drop the WWF tag titles to the Hart Foundation. “Vince [McMahon], in his infinite wisdom, had to have them drop the belts in the ring. Dynamite couldn’t even walk. Davey had to literally carry him into the ring,” recalled Bruce Hart. The gutsy, foolish move shows both the good and bad of wrestling — loyalty to one’s employer, who in turn coldly puts its own self-interests above anything else.

The Bulldogs never recovered. Returning to full-time action, the pair battled the champion Hart Foundation and Demolition but never again made it back to the top. They were gone from the WWF in November 1988, bound to split time again in Calgary (both had married local girls, and Dynamite was given the booking job) and Japan. Davey Boy decided to pursue a singles career and the team was done.

After a divorce, Dynamite would return to England, working where he could around the UK and Japan, often teaming with his old trainer’s nephew Johnny Smith (John Hindley). He retired in 1991 at 33 (with one, brief return in 1996), re-married, settled down to a regular job as his health continued to deteriorate, and had part of his leg amputated due to falling out of his wheelchair in October 2004. Brian Knobbs of the Nasty Boys went to see Dynamite during a tour of the UK in the ’90s. “He came out to the bar that night. He cried. We just had a good time because he didn’t see nobody in forever.”

If it was a Hollywood ending, Dynamite Kid would have been welcomed back into the wrestling community, feted for his greatness in grand spotlights, like a WWE Hall of Fame induction. Instead, he was essentially shunned.

Newspapers in the United Kingdom often sought out Billington for interviews, his status as a cripple after giving his life to the pro wrestling business too good a story to ignore.

“In America I fought alongside Hulk Hogan in front of 93,000 screaming fans at Wrestlemania. But once I was in a wheelchair there was nothing left for me to do,” Billington told the Sunday Mirror in March 2001. “I spent thousands of pounds on medical bills. Wrestlers do not have a pension and you risk your life every time you step through the ropes.”

A recent photo of Tommy Billington and Harry Smith, shared online by Smith after learning of the Dynamite Kid’s death.

Harry “British Bulldog Jr.” Smith, the son of Davey Boy, was among those to react to Billington’s death online — and among the few from the industry that kept in touch and visited when he could. “It deeply saddens me to announce the passing of Tom Billington the ‘Dynamite Kid.” I was really happy and glad I got to see Dynamite one last time last June in the UK. Dynamite was certainly an inspiration to myself and many others and really revolutionized Professional Wrestling as we now it today. He flew high, and gave it his all every match. Thanks for everything and sad to have lost another family member.”

Details on Billington’s death on December 5, 2018, are not known at this time. Another British wrestling great, Marty Jones, posted that Billington’s brother Mark “was at his bedside & thruout his long journey.” Billington had three children with his first wife, Michelle Smadu (sister of Bret Hart’s first-wife Julie): two daughters, Browyne and Amaris, and one son, Marek.

— with files from Steven Johnson

RELATED LINK