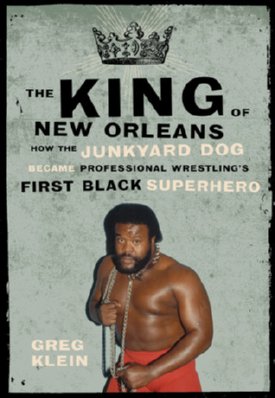

In the new book The King of New Orleans: How the Junkyard Dog Became Professional Wrestling’s First Black Superstar, author Greg Klein writes: “Sylvester Ritter and the character he became, the Junkyard Dog, is in danger of being forgotten in wrestling circles, and in New Orleans. I want to change that.”

Klein’s book should indeed change that, as it’s a fascinating and in-depth look into Junkyard Dog’s rise to superstardom, memorable feuds and his life outside the ring. It’s also a compelling tale of how the Deep South — a hotbed of racial intolerance during JYD’s formative years — became the home of wrestling’s most adored African-American idol of the ’80s.

Not merely a biography of the Junkyard Dog, but also a historical ethnography of the Mid South territory, the book thoroughly explores how JYD broke down colour barriers by becoming the first black wrestler to be made the top star of his promotion.

After recently reviewing The King of New Orleans for SLAM! Wrestling, I tracked down author Greg Klein to learn more about his extensive research, source material, wrestling fandom, and his remarkable story of the Junkyard Dog.

Q: In your book, you describe in great detail certain ’80s matches from Mid South. Do you have an extensive collection of Mid South videos, and if so, what do you have? (There never seemed to be much out there, in the form of commercially produced videos).

A: I admit, I have a lot of wrestling videos. I have had some people look at my videotape collection over the years, and comment, “Wow, you have a lot of porn tapes.” No, just wrestling. I still have a couple of tapes from the ’80s of Mid South that I taped myself. Unfortunately, I pulled an Ole Anderson and reused the tapes over and over, so I lost a lot of stuff. I then began tape trading to get it back. In the past decade, the Watts family has released a lot of their straight-from-the-master video and DVD collection. You can order directly from them at www.universalwrestling.com. Unfortunately, their collection begins mid-1981, so the early stuff isn’t there. However from 1981 on, they have everything including Mid South Wrestling, Power Pro Wrestling and Universal Wrestling Federation.

Q: Would you know who has all the Mid South footage from the weekly shows, and if it will ever see the light of day in the form of commercial DVDs? Would you like to see WWE acquire it for programming like Classic on Demand?

A: See above. Ene Watts, Bill Watts’ ex-wife and the mother of Joel, Erik, Micah and Ene Watts, got the tape collection in the divorce settlement. Her son, Micah, runs the business end of things selling the tapes. The rumor was the WWE offered them a million dollars for the rights and all the footage, but were turned down. You’d have to sell a lot of $20 tapes and DVDs to make that up, so I don’t know. When I was trying to get interviews with the Watts family, I asked Micah about that end of the business. Oddly he never granted my interview requests after that. I know they were trying to get the old tapes syndicated on something called Tough TV. Not sure what became of that. Personally, I kind of like that it is still the family business. Nothing against the WWE, but it worries me a little that they have control of most of the history of wrestling now. Their version of history isn’t completely accurate, you know? [EDITOR’S NOTE: Word is that WWE has indeed bought the Mid South footage from the Watts family.]

Q: In depth, you tell the story of your favourite Mid South match between Junkyard Dog and Hacksaw Jim Duggan vs. Butch Reed and Buddy Landel. Can you tell us of some other matches from that era that are especially memorable to you, and why?

A: I discovered Mid South about 1983, so I especially like the Butch Reed matches. I was a Reed fan from Georgia, so I was rooting for him to win the title, and the mark in me really enjoyed it. I also liked Buddy Landel as the sneaky, cowardly friend. I really like the Ted DiBiase-JYD match where DiBiase turns heel. It is just a textbook heel turn. When I wrestled, I used to like to turn heel. It is probably the best example of “telling a story” that the old timers used to stress to the green boys about how to wrestle.

Non-JYD, I was a big fan of the Midnight Express and Dibiase and Steve Williams tag teams. I saw a match at the Sam Houston Coliseum where Doc and Dibiase wrestled the Guerreros in a non-title bandalero on a pole match that was another one of those “classic matches of my youth” type of matches. As a mark, I also particularly enjoyed when Doc and Dibiase beat the Rock and Roll Express for the tag team titles.

Greg Klein.

Q: You write in your book that the match between the team of JYD/Duggan vs. Reed/Landel “was also one of the matches that led me to want to become a professional wrestler — but that’s another story entirely.” Can you share some of that story?

A: I went to Auburn University in Alabama and was a journalism major. I was editor of the college newspaper, had a lot of fun, learned a lot, etc. but wanting to be a wrestler never left me. Twenty years later, I am sure some of my fraternity brothers still have scars or memories of me doing wrestling moves on them.

At the same time, a buddy of mine from grade school and I started a wrestling newsletter. When we started it, we had no idea that the Torch or Observer even existed. And honestly, we were far behind them in terms of reporting, although we were better on design and editing than the Observer (haha). We did it for a year while I was in college, and decided to focus only on indie wrestling. It was a horrible time for the bigs (early ’90s) so it made sense. But we both wanted to be in the business and there was still a “dirt sheet” mentality among the boys so we stopped.

I took a job on the gulf coast of Alabama and started making contacts through the newsletter. I got referred to Adrian Street and he trained me (sort of), and off I went. I wrestled for four years in Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Arkansas, Delaware and Ohio. My first match was in Lucedale, MS in 1993 and my last match was more than four years later in Ohio. My names were Billy the Kid, J.J. Havok and in my final year, I had my biggest matches as a bootleg Doink the Clown.In 1997, I left Alabama and moved to New York to help take care of my grandmother. I had no contacts in the northeast so I stopped getting booked. Being a caregiver, it was hard to go away on long trips for matches down south, and one day, I didn’t want it as much as I had the previous ten years of my life. I learned the business, however, through the sheet and my years as an indie guy, and clearly that helped me with the book.

About the same time I decided to stop wrestling, I got an acting gig, and I saw it was a clear transition. I took classes in New York, went through The Second City, got my union cards, started writing plays and screenplays. My biggest thing so far, I was a henchman in season six of 24 making bombs and exchanging glances with the lead villains. I don’t think I was ever killed off, so I keep holding my breath for a movie!

I am always trying to sell a script or get a movie made or stage a play. I’d like to do a wrestling movie someday. I am not sure if The Wrestler has helped or hurt those efforts.I have been writing about my pro wrestling days in a book I am tentatively calling Weekend Warrior. I am not sure if ECW Press will publish it, or when it will be published, but you can look for it out there someday.

Q: Along with being a big fan of Junkyard Dog, you also mention being a fan of heels like Butch Reed. Can you elaborate a bit more on heels in Mid South — or other territories — that you especially liked, and why?

A: I think my first few years of fandom, I was a fan of the good guys, Bob Backlund, Rocky Johnson and the like. As I got to be a teenager, things changed. I stopped liking the good guys so much. Part of it was the teeny boppers. You know, it was hard to root for Magnum T.A. or Ricky Morton when all the girls were screeching for them. Hulk Hogan had about a six-month shelf life with me. Unfortunately he had about a five-year title run his first WWF go round. So I rooted for him to lose.

I compare it to music. When I was 10 or 12, I listened to American Top 40 religiously. I wanted my favorite songs to be No. 1, and when a song was No. 1, it meant a lot to me. When I was 17, I got into metal, and later I got into punk. Those songs weren’t No. 1. But they were better in my mind. They didn’t always get played on the radio. That was a badge of honor. Suddenly being popular wasn’t as important as having some sort of dark badge of honor. Typical teen stuff, I guess.

As a worker, I used to like being the heel much better than the baby too. Of course the babyface got to sell pictures and gimmicks and make more money. The good ones shared some of that money with the heel they worked that night. The bad ones gave the merchandise table kid crap and accused him or her of stealing. We used to always say, in real life heels were the nicest people, but in real life a lot of the babyfaces were actually jerks.

Q: In early chapters, your research is extensive in describing behind-the-scenes business in Mid South, especially in regards to promoter Bill Watts’ dealings with Leroy McGuirk, among others. Some of Watts’ quotes come from his book The Cowboy and the Cross, but what other sources did you use to get such an in-depth story on the business behind Mid South?

A: For whatever reason, I had a hard time getting wrestlers to talk to me. At the time, I was unemployed; we had gone through some rough days in California and my resources were limited. I had high hopes, but no one answered my emails or called me back. I don’t know why. Luckily I knew a lot of the storylines from growing up a fan. The backstory I dug out of several sources; the Watts book was huge. It was probably better than actually interviewing Watts. The Ted DiBiase book helped too.

Obviously The Wrestling Observer was invaluable. I can joke about his design style or editing, but Dave Meltzer should get a lifetime Pulitzer for his wrestling history. Even before I started wrestling, I feel like I learned the business from the Observer. Not that I liked wrestlers dying, but I used to learn so much about the sport from his obituaries. I used to write in a lot and tell him it was such a shame that it took a death to read his histories. I am sure he heard that a lot. Eventually he just started writing history stories without it being an obit.

I digress. The JYD obit in the Observer was important to my research. So was the post-Katrina history of New Orleans he wrote. I owe a lot to Meltzer and the Observer. Doesn’t everyone who writes about wrestling? I read a lot on the web too. Title histories. Kayfabe Memories. I read SLAM! Wrestling quite a bit too, especially the obits and tributes. It is still hard to find certain wrestling things online, but it is getting better all the time.

Q: Your knowledge of race issues and civil rights really shines when writing about the Deep South, and how JYD blazed a trail as the first black star in a predominantly white — and often racist — business. Can you tells us about your studies on race and civil rights, and where you went to school?

A: I went to Auburn in east central Alabama. I was a journalism major, I didn’t have official studies, but I learned along the way. My senior year we had several protests that I covered for the newspaper or wrote editorials about. One was by black students against the “Old South” parade; basically a couple of fraternities dressed up like Rebels soldiers and had a parade. It was really offensive, and I guess to them, it was their heritage or something. Anyway, that was a big influence on me. Later we had a gay rights protest; very ripped from today’s headlines in a way. I don’t know that I even was on the right side of those issues, politically at the time, but they started me thinking. They pointed me toward a greater view of southern history, and of tolerance.My second job out of college was back in central Alabama, in a town called Prattville. It was very close to Selma. One of my frat brothers took a similar job in Selma. Their offices were right next to the Edmund Pettis Bridge where the state police released the dogs and hoses on the marchers. Sometimes when I would go to hang out with my buddy, I would wait for him while he got his paper put out. I smoked then, so I would stand outside on the bridge and smoke. It is a tiny bridge; you don’t get that from the pictures or the stories. Talk about history. Just standing there, it affected me. Later, in the prelude to the ’96 Olympics in Atlanta, I covered the Olympic Torch being carried over the bridge. I took a picture at the time of a bunch of black kids running after the Torch, smiles on their faces. This was 30 years after Bull Connor and these kids were overjoyed. It affected me.

We drove from Selma to Montgomery one time to go watch football. You don’t really understand the idea of marching on that narrow winding, kind of dangerous road from the pictures. It affected me. I have driven through the sites in Montgomery, in Birmingham. Well, you get the idea. Along the way I started reading about that era, about Dr. King, about Rosa Parks, whatever I could find. I know that helped me see this part of the story that maybe another biographer might have missed.

Q: You write about the death of JYD at the end of the chapter Big-Time Decline. In your research, did you discover any details about his funeral and who all was there?

A: Again, the Observer was a big help. I also pulled the obit from Ritter’s hometown paper, in Wadesboro. Other than Buddy Landel, no wrestlers were there. Meltzer said Michael Jordan sent flowers. So did DiBiase, McMahon and the Funks.

Q: Tell us about the process of getting your book published by ECW Press. Did you shop it around first?

A: I had contacted some local people in New Orleans, an agent, stuff like that. “I don’t do that,” was the reply I got. Wrestling being wrestling, the stigma being the stigma, you know? So I zeroed in on ECW Press. I had a few of their books. I knew they had found a niche doing wrestling books and I knew they were treated with respect by the company. I didn’t know Michael Holmes, the editor was such a fan of wrestling himself, but when I found out, it made me very comfortable with them.

I did my homework, found out what they were looking for and send them a sample chapter. They asked for more. I didn’t have anything more. So I took another month, wrote two more chapters, an outline. It kind of went on like that. After about six months they accepted the book; set a publishing date way in the future. I did some research, finished, rewrote, edited. It has been a good process. I have nothing but good things to say about ECW Press. The people I have worked with there have been very kind, very helpful. We’ll see if they want to publish Weekend Warrior or if Michael has other ideas for me to write about.

Q: Your book is not merely a biography of the Junkyard Dog, but also a historical ethnography of the Mid South territory. When you immerse yourself so deeply in such a subject, do you tend to burn out on it, in a sense? Or do you find yourself with an even greater interest and enthusiasm for revisiting and watching Mid South matches, now that your book is done?

A: No. I get your point, because it does happen for me sometimes. I don’t watch much 24 anymore, although I had kind of burnt out on it by season six anyway. Sometimes when I am covering something or writing a screenplay, I get so into it that I do burn out. Mid South Wrestling, however, it has been the opposite. It some ways I am getting back into it. I don’t really watch modern wrestling, so if I do have that urge, I just pop in a Mid South tape. Or the Houston City Wrestling stuff I still have on tape. Again, I compare it to old music. The nice thing about putting in a cassette tape (man, I feel old mentioning cassette tapes) from the ’80s, it is also reminds you of who you were at the time. It brings back memories. I wrote this book to honor my memories. I wrote it to remind New Orleans and to remind JYD’s fans of his legacy. That part, I am not tired of at all.

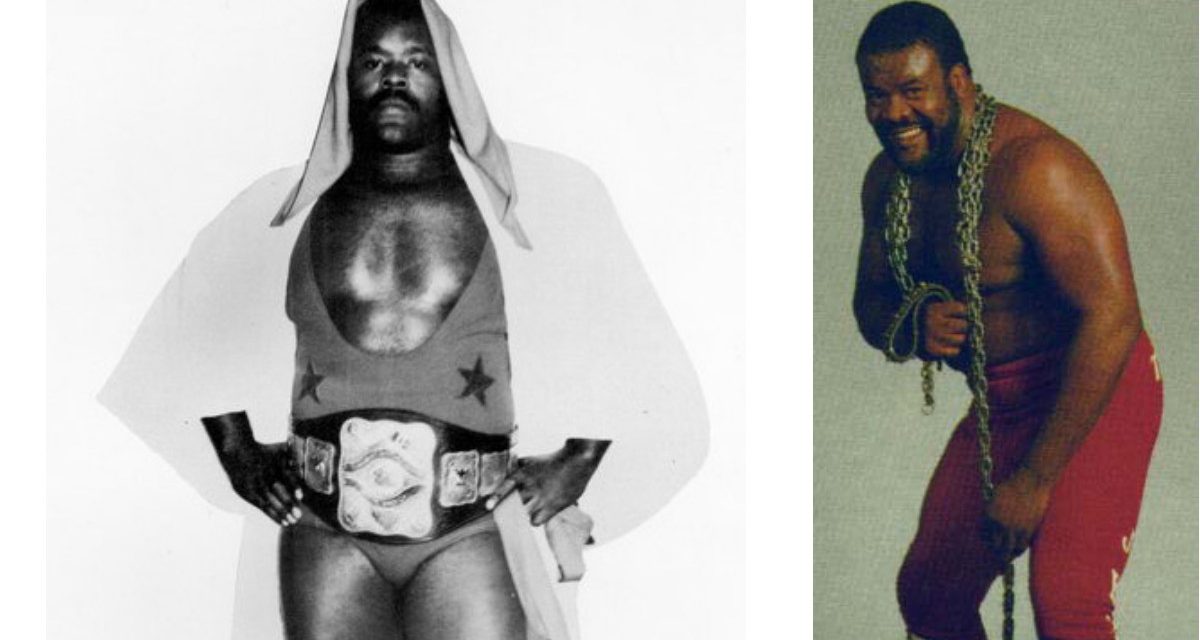

After he was King of New Orleans, the Junkyard Dog tried to be the King in the WWF.

Q: Are you a fan of any current wrestling promotions these days? Do any wrestlers capture your imagination in a similar way the Junkyard Dog did all those years ago? Do you think JYD’s influence can be seen in any specific wrestlers today?

A: I don’t watch wrestling anymore. My wife isn’t into it. My son is still too young. But I had soured on it even before they were in my life. I was buying old tapes and had become an old timer or sorts. Meltzer mocks it a little bit; the wrestling was better in my day crowd. Well, to me it was better. Not WCW circa 1990s, of course, but the territories or whatever. I just don’t relate to it like I did when I was that age. And that’s okay. That’s why the business has to make new fans, make new stars, create new angles. I am not bitter. I have nothing against Vince or WWE or today’s stars. If I ever get to make a movie about the business, I’ll use today’s guys just like The Wrestler did. I respect what they do. I just don’t like the product because it isn’t what I’m used to liking, I guess.

As for JYD, I would argue that you wouldn’t have had a guy like The Rock become such a big star, such a charismatic star, such a crossover success — and mostly free of racial overtones — without the success of JYD to pave the way. Just as you would not have had JYD without Bobo Brazil. In some ways it is like the black quarterback in the NFL. The first couple of successful guys affected each other, helped the next guy, but now it almost doesn’t matter. Now they all owe some debt to the trailblazers, but fortunately it has gotten to the point, where race is not an issue anymore.

Of course, I don’t watch today’s product, so I don’t know if there is race bating or stereotyping. Maybe there is. But I am speaking from the perspective of what I have seen.

Q: At the end of your book you include an induction application for JYD, that you wrote, to be considered by the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame. You also submitted one to the North Carolina Hall of Fame. Have you heard anything back from either? And what can fans of JYD do to support this tremendous effort you’ve made to honour his legacy?

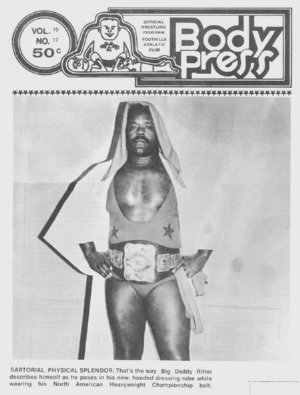

Big Daddy Ritter on the cover of a Stampede Wrestling program in December 1978.

A: So far the answer has been no. Louisiana has passed twice now and North Carolina once. No explanations. I think North Carolina may be the better opportunity long term since Sylvester Ritter had a distinguished high school and college sports career there. The trouble is, he was an offensive lineman. How do you demonstrate how good he was? He was a four-year starter in college, two-time all NAIA, a senior co-captain. That’s my proof. He was good. Is that Hall of Fame good? I don’t know. Add in his success in pro wrestling and maybe that gets him over the top. However it does not seem like the Hall of Fames consider pro wrestling as sport in terms of inductions. Ernie Ladd was inducted in Louisiana, but he was a high school and college legend there. Ric Flair, on the other hand, is not in the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame. So that’s the hard part.

I have some other ideas. I have set up an indiegogo crowdfunding account to honor Sylvester Ritter’s memory. People can donate at www.indiegogo.com/junkyarddog. The first effort is to raise money for a church in Hickory, NC, the GS Glory Church, being built by some friends of Ritter. Richard Johnson was a year ahead of him at Bowman High and Fayetteville State and one of his closest friends in life. Mr. Johnson’s wife is Apostle Kathy Johnson; she is the minister at the church. They have been building a new building and I promised them I would help. We are trying to raise $1,000 by the fall to donate in Sylvester Ritter’s name. We just launched the account, but it has been slow going so far. I am hoping some fans will give a few dollars to memorialize the Junkyard Dog.

Long term I would like to continue to do this in his name. In the fall, for football season, I am going to set up a second account to donate to Fayetteville’s athletic program in Ritter’s name. He is not yet in their Ring of Honor, but he should be, and perhaps a donation will help that along.I would like to see a statue in Louis Artmstrong Park in the Treme section of New Orleans. It is being built in the same complex where the Downtown Municipal Auditorium — aka the Dog’s Yark — stood. Over a five year span JYD drew more than a million fans to that arena, so of course there should be a statue of him in that park. I think he is as big a cultural icon as anyone else who is memorialized there.

I have been told by some city officials in Wadesboro, Ritter’s hometown, that they would put up a statue or plaque there too — if someone else paid for it, of course. Plus, I think Ritter’s grave is unmarked. I am not sure why. But if the family would allow it, I would like to raise some money for a headstone.

So those are my ideas. I am starting with the church donation and we’ll see if we can build some momentum. It hurts every time I see that indiegogo page and it is still on $0. It is a good cause, and it is in JYD’s name, so I hope that will change soon. Your readers can also follow me on twitter at @JYDbook. Hopefully I will have some good news updates along the way.

JUNKYARD DOG STORIES

- June 28, 2023: Illuminating the ‘Dark Side’ of JYD’s struggles

- May 30, 2012: Thump! New book restores Junkyard Dog’s legacy

- Dec. 3, 2011: Superfly, JYD, Samoans, Cornette among 2012 PWHF inductees

- June 5, 1998: Mat Matters: So long, JYD

- June 3, 1998: Junkyard Dog dies