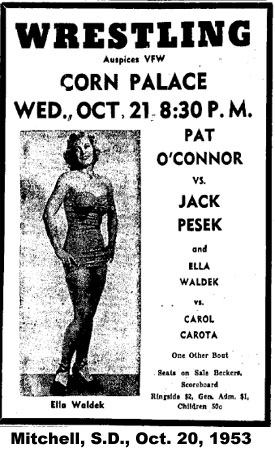

A natural blonde and a stunning physical specimen, Ella Waldek was one of the most golden figures of the Golden Age of Wrestling. She was also one of the most tragic. Her life story is an incredible tale of triumph over adversity.

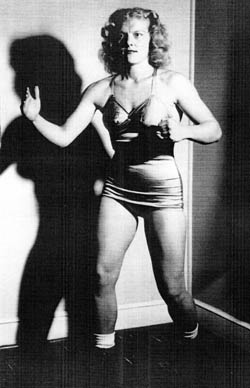

When she broke into the mat game around the middle of the last century, Waldek presented a vision of athleticism and sex appeal that had been seldom seen in the wrestling ring. At 5-5 and a perfectly proportioned 140 pounds, she personified muscular grace. She also had a ruthless aspect that, combined with an utter fluency with wrestling holds, led one wrestling magazine to deem her the “roughest, toughest girl wrestler.”

Ella Waldek in a classic pose. Courtesy Chris Swisher

Even in the stilted, hyperbolic sportswriter prose of the age, her skill and style shine through: “With blinding speed the girl slipped from one hold to another — nelsons and counters — body slams swiftly converted to roll overs, hammer locks spun out of, Boston Crabs unraveled with all the skill of a female Houdini, Short Arm scissors smacked on and countered with the fierceness of a Bengal Tigress. Only the true wrestling fans, the out and out connoisseurs of the Mat appreciated what they were seeing.”

That paragraph appeared in Wrestling magazine in June 1951. Even today, true wrestling fans know that there is hardly a female grappler alive who can convincingly accomplish the sequence of holds listed above.

The magazine writer predicted big things for the 20-year-old Waldek: “With a devil-may-care attitude, an utter contempt for any of her adversaries, a profound and complete belief in her ability to crush the opposition, she is fast gaining recognition as the logical successor to the throne of ‘Queen’ Mildred Burke.”

The next month, tragedy struck.

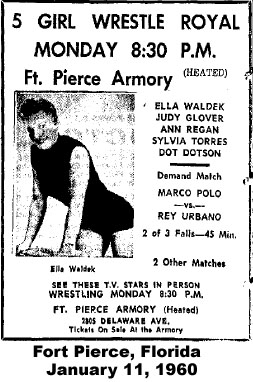

She was in the ring when one of her opponents, 18-year-old Janet Boyer, collapsed during a women’s tag match in Ohio. Boyer soon died, and, in the hubbub that followed, Waldek unfairly caught the blame for what remains the worst tragedy in the history of women’s professional wrestling. Reports implied that a Waldek bodyslam might have been responsible for Boyer’s death. Police questioned her as a criminal suspect before letting her go. Afterward, fans called her a murderer and came out to see her in droves.

Most fans of the Golden Age are at least aware of the story of Boyer and Waldek. For many, it is the sole reason they still remember Waldek. What they don’t know is the story is only one twist in an amazing, Dickensian life of hard knocks and adventures that led her from a Catholic convent to a World War II bomber factory to a Las Vegas casino to a roller derby rink and, finally, to the wrestling ring.

A woman in a man’s sport, she suffered the hardships of the pioneer, from unwanted male attention and exploitation to the strains of constant travel to the vagaries of her rough-and-tumble trade. She drove 100,000 miles a year in a big Oldsmobile 98 and kept a .22 Beretta in her big Mexican leather purse. A male wrestler attempted to rape her. An ill-placed kick to her stomach led to a catastrophic injury that cost her chance to have children. Her marriage collapsed. She narrowly avoided death in a harrowing car accident.

The adventure continued after wrestling, when she found herself working as a mall security guard, a security supervisor, a private detective and finally a greenhouse operator. Her local newspaper, the Tampa Tribune, profiled her under the fitting headline, “From Fighting to Flowers.”

Born to immigrants — her mother was German, her father Russian — she was baptized in the Lutheran faith and spent her earliest years on a farm outside of Spokane. Hers was anything but an idyllic childhood. Her parents worked as laborers and the family lived in a converted barn. Else Schevechenko was three years old when her father walked out, leaving her mother behind with Else and her older sister. It was a three-mile walk to school and a three-and-a half-mile walk to her mother’s job.

Else grew up fast, always the biggest kid in class. “I was raised on a farm driving tractors and throwing around 50-pound bales of hay,” she recalled in a series of recent telephone interviews from her home outside Tampa. “I went to school as Elsie the Cow. I was always bigger than everybody, more mature than everybody.”

She looked so mature that, at 10 or 11, she was able to work as a waitress with her mother in a drive-in diner. But she was eventually caught by authorities and given a choice: reform school or a convent. She chose the convent. By the time she was 14 she was looking forward to taking her vows.

Then her mother, newly remarried, arrived to take her home. It was not a happy home. The new husband had two sons and all of them eyed her like a piece of meat. “I overheard my stepfather say if the sons didn’t get me, he would. And I said, ‘That’s it. I’m gone.'”

To get out of that house, she got married, at 15. She had grown to her full height and filled out, looking like a woman instead of the teenager she was. But because she was underage for marriage in the States, her mother had to drive her across the border for the ceremony on an Indian reservation in Canada. She may have looked like a woman on the outside, but on the inside she was a child. The marriage lasted one night. (“He didn’t believe I was a virgin and he damn near killed me. If the maid hadn’t found me in the morning, I would have probably bled to death.”)

It was wartime, and with all the men gone she managed to get job as a mechanic working for the Air Force on B-24 Liberator bombers. “My job was to check out urinals, turret and bomb bays. Go up with just the pilot and radar man.”

But after her left leg was burned from ankle to knee in a chemical fire on one of the planes, she took a severance settlement.

She traveled around the West selling periodical subscriptions out of a station wagon. She worked as a waitress at a restaurant in Texas and then at a country club in New Orleans.

At 16, she ended up in Columbus, Ohio, preparing to be a roller derby professional. She took on the toughest position, jammer, and made an immediate impression. One of those watching was the wrestling promoter Tommy Ward. He asked if she had ever seen “ladies wrestling.” She hadn’t.

When she finally did, her first thought was: “My God, I can do better than that.”

She was watching Lillian Ellison, who would later become the “Fabulous Moolah,” and a woman who would go on to become Lady Angel. “Moolah couldn’t fight her way out of a paper sack,” Waldek said.

Wrestling was a godsend, something to harness Waldek’s boundless drive. “I was really thrilled that I was able to get something to use up all the excess energy I had,” she recalled.

She worked for the infamous promoter Jack Pfefer in Toledo, and ended up signing a contract with Ellison and her second husband, Johnny Long, who were based in Columbia, S.C.

She worked for about a year with Ellison, who was attached to no regular promotion. “There wasn’t a whole lot of matches because she was an outlaw,” Waldek recalled.

She said that she split with Ellison after a male wrestler tried to rape her before a match in Toldeo. Some nearby male wrestlers intervened to saver her, she said. “He was crazy,” she recalled. “He was a boxer. He was punchy as hell.”

Tommy Ward took her to see Billy Wolfe, the boss of women’s wrestling. There were three things about her that stunned Wolfe. “He couldn’t believe I was a natural blonde. He couldn’t believe I was just 19 years old. And he couldn’t believe I was not gay. He said nobody has a voice that deep who isn’t gay.”

In August 1949, at her first tryout for Wolfe inside Al Haft’s Gym in Columbus, Billy matched her against two of his biggest and toughest women, Johnnie Mae Young and Dot Dotson. Waldek said neither veteran gave her trouble. “Mae Young got me in a couple of holds and I got out faster than she could put me in. Finally, she said, ‘Let’s work together.’ The next day he put me in with Dot Dotson. Same thing. After a while she, ‘Said how bout working with me on this?'”

Waldek looked so mature that Wolfe inflated her age in the publicity sheets. “I was 28 for 10 years.” Billy gave her the name “Ella Waldek.” He said he picked Waldek from a little town of that name in Germany that he had heard about from a New York promoter. “He thought that would be a good name for me. But nobody’s ever been able to find a town in Germany called Waldek.”

Trained in the shoot wrestling style by a former collegiate wrestler, Waldek had talent to burn. “I was the only one who could do a short-armed scissors lift. On the body slam, I could always lift them higher and faster and still let them down easy.”

As the women sharpened their skills at Haft’s Gym, Waldek said they sometimes engaged in mixed matches with male collegiate wrestlers from Ohio State University. Waldek and another female powerhouse of the Golden Age, 150-pound June Byers, were glad to show the boys who ruled in the ring. “We spotted them about 10 to 15 pounds,” she recalled. “When they got in there they were so sure that they could beat any girl in the country. They never stayed in there for more than three or four minutes at the most. And that’s when we were playing cat and mouse with them. When they’d get in there with a pro, we’d beat those poor guys to death.”

Waldek said the college boys came out in a predictable crouch and tried to get the women in front headlocks in order to muscle them to the mat. “They came in there like fighting dogs and then they realized they were out of their league. We were 10 times faster than they were and we knew too many holds. We’d get them in arm locks, wristlocks. We’d keep them in a body scissors for a while or put on a Japanese toehold and they would start screaming. We’d get them up in a body slam position and they were scared to death. It was fun. We were glad to do if for Al Haft. It really brought the people in for the show.”

Waldek said Wolfe used her as one of his “policemen” who wrestled the up-and-comers before they got a shot at the champion, Mildred Burke. She said Wolfe, the notorious womanizer, never propositioned her but kept his controlling eye on her. She recalls earning $600 for a single match in Cuba in the 1950s and having to fork over $300 of it to Wolfe for his manager’s commission. “He would never allow me to make any money so I could get away. He made sure if I made any money he’d make me stay off wrestling for a couple of weeks. He never wanted me to make any money so I could leave.”

She said Wolfe and Burke were wary that Waldek might go off the script and take Burke’s title. “I don’t think I worked with her more than four times the whole damn time I was there. She was afraid to work with me. She had a complex that somebody was trying to knock her off or double cross her.”

Waldek, who always wrestled as a heel that was forced to lose to the champion, had a low opinion of Burke in the twilight of her career. “She had the publicity buildup. You can make anything from the publicity. People are gullible. They’ll eat up everything. As far as ability, she didn’t have it. If it wasn’t for her working with somebody good in the ring, she didn’t have it.”

Waldek had much better appreciation for Burke’s rival, Nell Stewart, another blonde goddess of the Golden Age who, like Waldek, had started out as a heel. “I was a natural blonde and she was a bleached blonde,” Waldek recalled. “She was a good actress and a good opponent. She knew what she was doing and she did it well. We worked very well together. She drew the crowds and so did I. If I was in the ring with Nell there were more photographers than customers.

“She had a special gift of the ability to portray feeling and action at the same time. Every time I ever worked with her, we always had the people standing. After we had a match, I can’t remember ever looking at a sports section, anyway, that wasn’t covered with pictures of her and I. I think everybody compared she and me as to being the two best as far as entertainers were concerned. We were the two that were asked for more.”

In the early 1950s, during one of Waldek’s bouts in Dayton, Ohio, she had an encounter with “Hatpin Mary,” the notorious spectator who used her eponymous weapon to stick wrestlers who came too close to her ringside seat. It was one of the first women’s bouts to be televised, and the audience was enjoying a free beer night. Mary took the occasion to stick Waldek in the leg. Enraged, she issued a challenge to her tormentor.

“Come up here, I want to show you what you have done,” Waldek.

When Hatpin Mary unwisely climbed into the ring, Waldek shot out a drop kick that barely missed her face. Mary lost control of her bladder, standing near a brand-new robe that Waldek had spent hundreds of dollars on.

“She just let her water go and she went all over that robe,” Waldek said.

Her moment of lasting notoriety came on July 27, 1951, when she faced 18-year-old Boyer in East Liverpool, Ohio. Boyer had just come in off the road doing Athletic Shows and she was bruised and beat up. “I kept telling her, Janet, you should have told Billy you were sick,” Waldek recalled.

Waldek said Boyer had a big lunch before the match, “this great big hamburger with raw onions on it and drank a Coca-Cola.”

They had a singles match before a tag-team match with Johnnie Mae Young and Eva Lee. “We got through the first singles match fine,” Waldek recalled.

In the tag-team match, Boyer tagged out and dropped down on the canvas. “I guess I was the one who yelled to the timekeeper, ‘Get her off the mat, she can’t lay there and sleep.’ But I knew something was wrong.”

Boyer died a few hours later. Waldek, Lee and Young were confined to a hotel for a night while police questioned them. They were eventually released without charges. The coroner later found a ruptured stomach and a subdural hematoma on Boyer’s skull; either could have killed her. Waldek thinks the large pre-match meal contributed to it. “She died because her stomach bursted,” Waldek said.

Waldek had bodyslammed Boyer in the first match, and when that fact came out in the papers the public began to blame the death on Waldek. She said Billy Wolfe’s comments fanned the flames. “Bill then wrote in the Columbus papers that I had killed Janet Wolfe,” Waldek said.

The publicity brought her infamy, but it made her hot at the box office. “I drew the biggest damn houses in the world. It was terrible. But it faded away like everything else does. Course, the magazines kept at it like they always do. Right after that Mille Stafford broke her leg in Dayton, flying out of the ring while we were training. I was the one who threw her, and she didn’t fall right. That was another hit on me. Anytime anybody got hurt they wanted to know if I was the one in the ring.”

Her own personal tragedy in the ring occurred several months later, when Cora Combs kicked her in the stomach during a match in a small town in the mountains of West Virginia. The toe of Combs’ boot smacked full force into Waldek’s side right below her ribcage, causing massive internal injuries. Waldek felt the pain, but soldiered on, even refereeing for the male wrestlers after her match. But after Waldek got back to Columbus, she collapsed.

When the surgeons cut her open, they found “both ovaries damaged, tubes completely destroyed, stomach torn loose and fallen down to the rectal area.” She lost one ovary, but the surgeon fought to save the other one.

“I had just turned 21,” Waldek recalled. “He knew I understood I couldn’t have children but he didn’t want me to go through the change of life so soon. Two years later they had to take out my other ovary and I went through early menopause.”

She had been married to her second husband only a few months, and the union collapsed after she could no longer have children, she said. She was out of wrestling for nine months, and during her rehabilitation she got a job working with her mother in Columbus at a glass factory that made television tubes. “I had to do something,” she said. “I had to help support my mother and sister.”

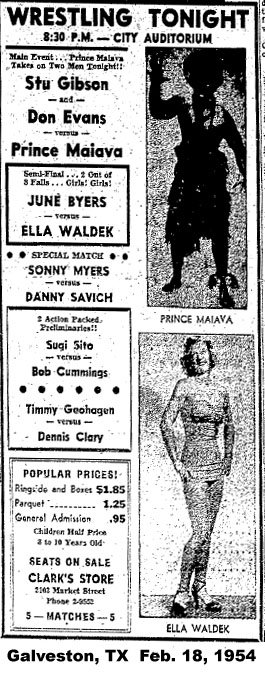

Eventually, she told Billy Wolfe she wanted to start wrestling again. “It was a job. I don’t know that I loved it. I did it as a job and I was happy with it.” In 1953 and 1954, she witnessed the chaos that befell women’s wrestling after Burke and Wolfe divorced and then started fighting over the business. The quality of wrestlers started to decline. “Billy Wolfe was getting all these young little fancy schmancy girls. He wasn’t getting the girls that looked like athletes.” At one point, she said Wolfe wanted her to be the new champion. “I have a letter he wrote me asking me if I would take the world’s title,” she said. “I was shocked as hell.” June Byers eventually became the one who replaced Burke as champion, before Moolah began her long run atop the women’s end of the business.

That business never recovered its earlier heights. Waldek did partake in one of the last shining moments for the women. She wrestled at Chicago’s Marigold Arena in July 1955 in some of the first women’s matches after the Illinois state athletic commission, bowing to a court ruling, approved female wrestling in the state.

Ida May Martinez, Ella Waldek and Penny Banner in 2004. Photo by Greg Oliver.

In the mid-1950s, she moved to Florida to work for Cowboy Luttrall out of Tampa. She won a world championship in Florida and continued to wrestle into the early 1970s, as the women’s end of the business did a slow fade.

As the wrestling petered out, she trained to be a security officer and moved into detective work. She had her own agency for a while, and then worked as a special deputy for the sheriff’s department before joining Wackenhutt as an undercover store detective. Later, she worked for as head of security for four years at Montgomery Ward’s and 13 years at J.C. Penny stores in the Tampa area. She put her skills to work wrestling with shoplifters. Her security career ended when she confronted a team of six professional shoplifters and was thrown against a plate glass window. “They almost broke my neck,” she said.

Through the security business, she met her third husband, James Mecouch, who was head of security at Maus Bros. Together they started a greenhouse on seven acres in Lutz, Fla. They ended up with four acres of woody ornamentals and eight greenhouses. They were married 31 years.

After her husband passed away in 1987, she reconnected with some of the women from the Golden Age at the Cauliflower Ear Club conventions in Los Angeles, eventually joining the board of directors and spending time with both Mildred Burke and June Byers. “At the CAC, I had more contact with June than any other time. She was very introverted. She just didn’t associate with anybody that much.”

She and Therese Theis even visited Mildred, who was ill and somewhat reclusive. “We really didn’t get to know each other when we were wrestling. Therese and I went to her house.”

Today, at age 81 with a bad back and some breathing problems, Waldek still enjoys the Florida sunshine and can still easily conjure up the shining moments for women during the Golden Age of wrestling.

“The people didn’t come to see the guys, they came to see the women. The girls were more colorful. I was one of the first people to get on the top rope and do a belly buster. We were the ones that drew the crowds. We were faster. We were flashier. We tried more dangerous things. The guys would all say, oh, you’re littler, you’re lighter. That didn’t have anything to do with it. It was being able to get up there and have the guts to try it.”

RELATED LINK

- Apr. 13, 2013: Women’s wrestling legend Ella Waldek dies