Perhaps the most significant date in wrestling history is March 23, 2001. It was on that day that the future of professional wrestling changed forever when the WWE (then WWF) announced its purchase of long-time rival World Championship Wrestling.

“It (WCW) was Ted Turner’s baby. And everyone thought he was always going to support it, no matter what,” said wrestling columnist Bryan Alvarez. “So the merger with AOL Time Warner and Turner being out of power, and thus, not being there to save them, was inconceivable.”

Going through the economics of all the transactions is best left to an MBA, but in its simplest terms, Time Warner acquired Turner Broadcasting System in 1996, leaving Ted Turner less of a major player in the companies and stations he helped create; in 2000, Time Warner and America Online announced a $181-billion merger. The resulting shakeups in management and corporate strategy doomed the money-losing WCW, especially when WCW programming was cancelled on both TBS and TNT. A wrestling company without a TV deal was less than appealing to the few suitors out there, and Vince McMahon jumped on the opportunity to buy the assets of his floundering competition.

It would be easy to point out all of the bad business decisions and mismanagement that led to WCW’s ultimate demise. But there is really nothing humorous about people being out of work and not being able to support their families. It was a tough time to be involved in the business. Ten years later, some of those people share their memories of those chaotic last days.

Despite its ending, there was a time when WCW was the number one wrestling company in the world.

“They had several years where they were super successful, even after they were making all sorts of mistakes,” Alvarez said. “In their best year, they grossed a little less than half of what the WWE is doing now. And at the time, nobody had ever made that much money in wrestling in the United States. In the spring of ’98, they had a string of sell-outs and business was through the roof.”

When the World Wrestling Federation was about to skyrocket into the world of sports entertainment in the ’80s, with the birth of Wrestlemania and the popularity of its main star Hulk Hogan, Jim Crockett Promotions — the main company behind the NWA — which would later become WCW, was striving to keep up, with stars like Ric Flair, Dusty Rhodes and Magnum T.A..

J.J. Dillon, though best known as the manager of the Four Horsemen, also served behind the scenes of both the WWE and WCW, and is uniquely qualified to shed some light on what happened.

To many, it appeared that the rival companies were running just about neck and neck at the time, in terms of popularity.

JJ Dillon.

“To this very day, I have fans tell me that they used to arrange their entire lives every Saturday, to get home by 6:05, so they could watch the NWA,” Dillon said.

“Wrestling at 6 o’clock on Saturdays made TBS. Period,” said Rhodes on the ROH Secrets of the Ring DVD. “And they treated us like red-headed stepchildren. They would have cameramen who’d never run cameras before.”

Despite the hallowed time slot on TBS on Saturday nights, the Crocketts found themselves in financial trouble in the late ’80s and ended up selling the company in 1988 to Ted Turner, who owned TBS. The Crocketts “were like the Kennedys” around Charlotte, Rhodes told Bill Apter in 2004 at the Mid-Atlantic Legends Fan Fest 2004. “Our business took a big fall when the Crocketts were bought out by TBS.”

“Ted Turner only had us on TV for one reason, and not because he liked me, not because he liked Jim Barnett, not because he liked to watch the wrestlers. He was looking for ratings. So as long as the ratings were good, nobody said a word to you,” recalled Ole Anderson in 2003.

“My career in the NWA was about 28 years. But I wouldn’t have been wrestling if I knew the business was going to change the way that it did, because it became a joke. I always considered wrestling a business,” said former NWA Heavyweight Champion Ronnie Garvin. “Life is not a party. I was always very serious.”

Everyone in a position of power seems to go through some degree of criticism at one time or another. But Turner seemed to be well respected as a businessman.

“Ted Turner actually called up Vince McMahon when Vince had a show on TBS, and wanted to form a partnership. But Vince said no. That decision by Vince drew the eventual battle lines between the two of them,” Dillon said. “The Crocketts provided the TBS programming in the ’80s, and with it came sudden success at a level that had never been enjoyed before. The Crocketts never built an infrastructure to develop a long-term plan to ride out their period of prosperity. Late in the ’80s, they hit a few bumps in the road and got in financial trouble. Ted saw an opportunity to protect his wrestling programming and to become a promoter himself. TBS purchased Crockett Promotions. Ted again called Vince and told him that he was now in the wrestling business. Vince told Ted that he would ‘kick his ass,’ and the rest is history that played out over the next 12 years.”

The official name change to World Championship Wrestling happened around the same time as the sale.

“So, Crockett sells his business — when you sell a wrestling business, you’re selling blue sky — to Turner. And Turner, not knowing anything different, calls his wrestling WCW, World Championship Wrestling, because that’s how I had run the thing for a couple of years,” recalled Anderson, who had run Georgia Championship Wrestling on TBS.

WCW started having problems almost immediately after Turner took over. It was already losing money and a lot of the major stars were leaving and heading up north to work for the competition.

“This thing started to change, TBS,” said Rhodes on the ROH DVD. “Crockett sold to TBS and the rest is history because it became a corporate football; you’re not one of the boys, it wasn’t a family-owned business. It went to hell, it went to hell in a handbag, and we knew it would.”

Oftentimes WCW would assign active wrestlers to managerial positions in the office, like Rhodes, who may have been the most famous booker in the company’s history.

It was a thankless job, he said. “I got more heat from the offices because I played with my heart more than I did my head sometimes,” admitted Rhodes, pointing out that at the peak of JCP, the company would be running four towns with with almost 100 wrestlers. “Sure some of them are going to be pissed off. I don’t blame them.”

Rhodes is credited with some of the most innovative ideas in wrestling history; whether those ideas were good or bad, they always had people talking. Of the gimmick matches, perhaps Rhodes’ best one may have been War Games, a double ring/roofed cage, which debuted in July 1987 during the Great American Bash tour.

“I had just seen Max Max: Beyond Thunderdome with the big cage. I asked if Bill Kleinbeck, our cage and ring designer, could put two rings together and create a roofed cage with a door on each end,” Rhodes recalled to Alan J. Wojcik. “The night before I had seen a hockey game and remembered a guy being put in the penalty box. I said why not put two teams together where two guys go for five minutes. Then have a coin toss and the winning team gets a 2 on l advantage for two minutes. Then every two minutes we add a team member. Then after everyone is in have the match end with a submission or surrender. It was a big money draw. The original matches were the best.”

“War Games was brutal. It was violent. The worst injury I ever suffered was at a War Games in the Omni in Atlanta,” Dillon said. “(Road Warrior) Animal had me on his shoulders and Hawk was poised to fly off the ropes with the clothesline, but there was such a confined space, where I was almost touching the roof of the cage, and there were all these bodies around. I tried to avoid landing badly in any way. I ended up separating my shoulder. I didn’t break it. But a separation can actually be worse than a break.”

Fans seemed to love the dangerousness of the War Games matches. Considering the demographic, it could not have been done anywhere else but in WCW. However, when Rhodes tried to capitalize on the success of War Games by introducing more gimmick matches, they did not go over as well.

Former NWA Heavyweight Champion Ronnie Garvin had the opportunity to participate in a match called the Tower of Doom. It was essentially a cage-like structure that had several different layers, and it would be contested between two teams of five. Just like War Games, the team members would enter the structure at different intervals, but instead of going through a door to enter the cage, they had to climb a ladder to the top, and work their way down. Garvin was not amused.

“I never liked the gimmick matches. I thought it was bullshit,” Garvin said. “I’m not an entertainer. I always thought wrestling happened when the bell rang.”

And of course, who could forget the infamous Chamber of Horrors match? Abdullah the Butcher certainly can’t. The image of Abdullah in the electric chair to end that match cannot easily be erased. But interestingly enough, Abdullah had no problem with it.

“I thought it was great. Somebody else was actually supposed to do it and turned it down, so I stepped up and said I’d do it. They had the electric chair set up and I had somebody in it and we were supposed to make the switch and then Cactus Jack flipped the switch,” Abdullah said. “People actually thought it was real. I had people from Japan calling me to ask if I’m okay. It was great.”

In 1992, Bill Watts took over as the Executive Vice President of WCW. Watts had been the promoter of the Mid-South region (Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi) before attempting a national promotion with the UWF. Watts was known as a no-nonsense kind of guy. His tenure in WCW wasn’t a long one.

“I always made my own decisions. I never really asked people what they wanted and why would I? In any other business, nobody tells the owner what to do. But I was always open to feedback,” Watts said. “None of the things we did back then were really ‘my’ ideas. You don’t copyright ideas in wrestling, but you make them work.”

Ron Simmons reigned as the World Heavyweight Champion during Watts’ period in charge.

“I went to bat for the black athletes back then. I always thought that Ernie Ladd was a brilliant guy and at first, I didn’t even like him. But I cried for four days when he died,” Watts said. “Our highest demographic at the time were the blacks. We had a very high black audience, but we didn’t have a black champion. How dumb was that?”

Watts eventually quit/was forced out of WCW, because although he loved wrestling, he was completely fed up with the corporate side of the business, and did not appreciate the way things were run there.

“I enjoyed working with some of the guys in WCW. But I didn’t enjoy the corporate stuff or the politics. The arrows I got in the front I didn’t mind so much, but it’s the ones you get in the back that hurt,” Watts said. “Take Jim Ross for example. He’s a guy that I started, and he was the best that they had. And they let him go. I have some good memories of my time there. But it was a long time ago and I really don’t dwell much in the past.”

Watts was replaced by Ole Anderson, who was then replaced by a young man named Eric Bischoff, who was very good at selling himself to upper management, but did not have the best reputation.

In 1995, Bischoff was posed with a question that would change the course of history. Ted Turner looked his way and asked “what do we have to do to compete with the WWE?” The question could not have been asked at a better time, because it was not a great year for the WWE. They were losing money hand over fist, and fans were starting to get increasingly bored with their product. Bischoff asked for a prime time slot to debut a new wrestling program, Monday Nitro. To Bischoff’s surprise, Turner approved and the war was on.

Eric Bischoff.

In a 2009 interview with the Pro Wrestling Torch, Bischoff addressed his relationship with the company’s top man. “Ted Turner had no idea what we were doing. Ted Turner from a creative point of view and strategic point of view, he knew the big picture, obviously,” said Bischoff. “He’s the one who gave us TNT in prime time and he approved budgets and approved a lot of the things I was doing in order to not only be competitive, but to be in the position I was in for a year and a half or so in dominating the business. Ted had nothing to do with that.”

Bischoff took the company to heights that it had never reached before. He also capitalized on the WWE’s financial struggles and ended up signing some of their top stars.

By the end of ’96, the roster boasted huge names such as Hulk Hogan, Randy Savage, Roddy Piper, Scott Hall, and Kevin Nash, among others. WCW was on fire at this time, and in the summer of ’96, they created perhaps the greatest angle in company history, the NWO.

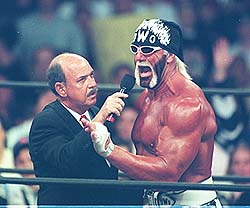

Mean Gene Okerlund interviews Hulk Hogan of the NWO.

“The New World Order was Eric Bischoff’s idea. If you watch the Bash at the Beach, by the time Hogan’s done doing his interview, he’s calling it ‘New World Organization, brother,'” Scott Hall told the Pro Wrestling Torch. “He already forgot the f’in’ slogan. It was Eric’s idea. You gotta give him all the props. He thought of somethin’ different. T-shirts sold like crazy. Because they were cool. You could wear that, like, in a bar. Instead of wearing a t-shirt around with Austin’s face on it, you could wear NWO.”

Ted “The Million Dollar Man” DiBiase was one of the major WWE stars that Bischoff was able to sign. DiBiase had already retired from in-ring competition by that point, but he was utilized as the original spokesman for the NWO.

Ted DiBiase in WCW.

“The major storyline which I was apart was the NWO, but maybe the bigger storyline to fans was the competition between WCW and WWF. People actually thought that WWF guys were trying to take over WCW,” DiBiase said. “What Turner did was buy stars that had already been created by Vince (McMahon). But they (WCW) were so unorganized to the point where they were minutes from going on the air and they were still talking about what to do for the final segment of the show.”

Of course the major problems didn’t start in WCW until a couple years later. But in the meantime, Bischoff was sitting pretty.

Alvarez was writing for both Figure4Weekly and The Wrestling Observer, and had been keeping track of the weekly happenings in the wrestling world.

A few years after the eventual demise of WCW, Alvarez teamed up with a newsletter subscriber Randy Baer (RD Reynolds), who had already put out a book for ECW Press (WrestleCrap), and together they wrote another book called WrestleCrap and Figure Four Weekly Present: The Death of WCW.

Flashback to ’96, and both reporters were still enjoying their lives as fans.

“WCW was very successful for at least two years during the Monday Night War,” Baer said. “In fact, as fans, we didn’t know how good we had it. We had the ultimate power to switch back and forth, between the two wrestling shows.”

By 1997, WCW was still on fire, but not only due to the popularity of the NWO angle. A large part of that success was because of the international talent that was signed, who were having unbelievable matches on a daily basis. Wrestling manager Sonny Onno came over as part of a talent trade between WCW and New Japan Pro Wrestling in 1995. He was close friends with Bischoff and remembers the change of scenery quite well.

“In Japan, I was used to being in much smaller venues, so I was very happy to be involved in WCW, even though my involvement was very minute,” Onoo said. “Some of the guys there were bigger than life. Their personalities were pretty much the same as on television. They would go clubbing and act just like they do on TV. If you take a guy like Meng, he probably was legitimately the toughest guy there. But he’s also a very gentle and kind individual.”

Sting.

By the end of ’97, the NWO was still the hot topic at the water coolers. But WCW had also embellished and enhanced Sting’s character, to the point where people were starting to believe that he was the one guy who could take down the NWO.

“The man whose career the Monday Night War helped the most in my opinion is Sting. He was such a mysterious character and had more drawing power,” Dibiase said.

So at Starrcade of that year, the big match on the marquee was Hogan vs. Sting for the title. It was a match that fans wanted to see for a long time, but the payoff wasn’t exactly what they were hoping for.

“The biggest WCW pay per view ever was the Starrcade with Hogan and Sting. If you look at the Hogan/Sting build, I don’t think there has ever been a better build in wrestling,” Baer said. “Usually feuds would just start, continue and end. But this one was over a two-year period. I’m surprised WCW had the patience to let that happen.”

Sting did end up winning the title that night, with Bret Hart as the special referee. But the ending of the match was so controversial that fans couldn’t care less. It was almost like an unofficial victory for the NWO. And that may have been the point in time, when WCW jumped the shark.

“Here was Sting, who was Mr. WCW, and everyone was thinking that finally the NWO was about to get their comeuppance. But there was a fast count,” Baer said. “They could have easily had Sting come out and beat Hogan to a bloody pulp. That was the main problem. Guys in the NWO were coming out on a weekly basis and telling us that WCW sucks. And the problem is that WCW never made its comeback.”

At the same time, Bret Hart had just left the WWE and came to WCW. But he was underutilized right off the bat, which didn’t really surprise anybody.

Bret Hart in WCW, perhaps asking why he was not better used.

“There was not a hotter free agent than Bret Hart. But going back to what Vince (McMahon) said over and over again, and he was right, ‘WCW would never know what to do with a Bret Hart,'” Baer said. “It’s like you could be the coolest guy in high school. But if you go to a party where nobody else is cool, that makes you uncool too.”

WCW was still very successful up until early ’99. One thing they were famous, or infamous for, is when they were on the air live, while the WWE was taped, and Bischoff had the idea of giving out the results of the competition’s show on his live show, so fans would not be switching back and forth between the two brands. However, by this time, it didn’t quite work like he’d hoped.

“WCW was owned by a broadcasting company. They wrongfully thought they were heading in the right direction, because television ratings were up, even though all other revenue was tanking,” Dillon said. “There was one night I remember, where we did our show live, and the WWE was taped. Eric Bischoff was in Tony Schiavone’s ear, and told him to give out the results of the WWE show on the air. It actually ended up having the opposite effect, because a large portion of our audience switched over to the WWE to see it happen. Our ratings tanked.”

The year 1999 was not a great one for WCW. It finally lost a ratings night to the WWE after 84 weeks of being on top. People were starting to get bored with the NWO, because nothing new was brought to the table. In the meantime, there were several disgruntled employees in the locker room who were waiting for a big break. Of course, none of them ever really got it, except for one man, Bill Goldberg.

“The only guy they really created was Goldberg. Every other star there was created by Vince. Goldberg had a certain look and ring presence, but he was never a great wrestler,” DiBiase said. “By the time the NWO had run its course, it was over. They had no new storyline. And Bischoff kept saying that he wanted to put Vince out of business. I said ‘are you kidding?’ In the end, it was the opposite that happened.”

Goldberg had built quite a reputation for himself. He was promoted as undefeated, allegedly 173-0, and seemed to be unstoppable. When Kevin Nash ended the undefeated streak in December of ’98 at Starrcade, it may have turned fans completely off of WCW. Here was their hero Goldberg, set up to be just another victim of the NWO.

Things were about to go from bad to worse in WCW. Some of their big stars were leaving, and most people in the company were unhappy.

“The way they had presented the NWO, they were the bad guys, but it was almost as if they were glorifying evil. I was a heel, but I was a big mouth coward. But when you’re a tough guy heel, everyone likes you. Stone Cold was a tough guy heel and he eventually became cool. But if I’m watching that, I don’t want my kid’s hero to be the guy who’s coming out and flipping people off, drinking beer and swearing,” DiBiase said. “I wasn’t happy with the way business was done in WCW. I didn’t even attempt to renegotiate my contract at the end. My heart had left it at that point.”

When former WWE writer Vince Russo came on board to head up the creative end in the fall of ’99, everyone was expecting things to be different. Things did change, but not for the better. By this time, Bischoff was also removed from his position and a lot of people criticize Russo for putting the final nails in the coffin.

Goldberg. SLAM! Wrestling file photo.

“I think the real doom came when Goldberg was beaten. Then they brought in Vince Russo and he did a lot of damage, but the place was still salvageable after they dumped him the first time. But then they brought him back, and by the time he was finished a second time, it was pretty much beyond repair,” Alvarez said. “Every week in the Observer and Figure Four, we would write about the weekly happenings. Nitro would be horrible, but we wouldn’t have a lot of time to dwell on it, because a couple of days later, Thunder would come on and everyone would forget about how horrible Nitro was, because Thunder was just as horrible or worse.”

It was a tough time for everyone involved. Most of them had families to support. Former WCW referee Scott Dickinson remembers the paranoia backstage.

“Numbers were dropping really fast, and Eric (Bischoff) had just been let go,” Dickinson said. “They were cutting guys left and right. Everyone was kind of looking over their shoulder.”

The changes in the business, from Turner to Time Warner to AOL Time Warner doomed WCW, despite the need for programming. The major move was AOL Time Warner’s decision to merge the company’s channels — TBS, TNT, Turner Classic Movies, the Cartoon Network and all of the CNN networks — into the WB network.

“Turner was a good man, but some of the people who ran it, didn’t take care of business. I think that’s why Turner sold it,” Abdullah said.

Initially under the new structure, WCW started to pick up the pace a little bit. But it still was not enough to be the saving grace of the company.

“Looking back at the last couple months in WCW, the TV was actually all right. But by that point it was too late. They were dead,” Alvarez said.

It was Jamie Kellner who actually made the decision to pull the plug from WCW’s life support machine, cancelling programming on both TNT and TBS. Kellner was in control of the new WB network of stations, and didn’t think that WCW fit in with the new image of the company.

Up until Kellner dropped the ax, there had been a few suitors, including Bischoff’s Fusient Media Ventures; no time slots meant no deals. Few saw WCW ever falling into the hands of Vince McMahon.

Officially, the deal took place on March 23, 2001. A sale price was never “officially” announced.

“This acquisition is the perfect creative and business catalyst for our company,” said Linda McMahon, chief executive of World Wrestling Federation Entertainment Inc. at the time. News reports had WCW losing an estimated $80 million US since the summer of 2000.

“We think the WCW has found its proper home now,” Turner spokesman Jim Weiss said.

“At the end, WCW desperately tried to cut back and they were letting talent go where contractually possible. They were cutting everything they could, but were doomed because of the guaranteed talent contracts. Bischoff was always spending somebody else’s money,” Dillon said.

“Of course it was smart because (McMahon) acquired all of that content,” Bischoff told the Torch. “Although he bought his competition for pennies on the dollar, he acquired a pretty vast library which was the only real value in the WCW transaction at the time. The way the contacts were written, he couldn’t and probably wouldn’t have forced the talent to come and work for him. Nobody wants high-priced talent that doesn’t want to be there. So I think the acquisition in the way he did and the reason he did it was smart. It was simply a business transaction and, just based on the value of the library alone, I think it was a brilliant transaction.”

The final episode of Monday Nitro aired on March 26, 2001.

“They always refer to it as The Monday Night Wars. It should have been called The Monday Night Battles. Vince was losing battles, but he ended up winning the war,” concluded Dillon.

— with files from Greg Oliver

RELATED LINKS